Ultrasound-guided adductor canal block offers superior post-operative analgesia and fewer opioid-related side effects compared to conventional intravenous morphine in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy.

Dr. Arvind Karoria, Department of Orthopaedics, SRVS Medical College, Shivpuri, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: doc.arvind88@gmail.com

Introduction: Effective post-operative pain management is essential for early recovery and patient satisfaction following knee arthroscopy. This study aimed to evaluate the post-operative analgesic efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided adductor canal block (ACB) compared to conventional intravenous morphine analgesia.

Materials and Methods: This randomized, controlled, interventional study was conducted in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) of the Department of Anesthesiology in an Indian Hospital. Eighty adult patients (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] I–II) undergoing unilateral knee arthroscopy under general anesthesia were randomly divided into two groups: Group M received intravenous morphine (0.1 mg/kg) before incision, and Group B received an ultrasound-guided ACB with 15 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine before extubation. Post-operative analgesic efficacy was assessed by the requirement of rescue analgesia and the time to achieve a Visual Analog Score (VAS) <3. Adverse effects and antiemetic requirements were also recorded. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0, and a P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results: Both groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, ASA physical status, and pre-operative vitals (P > 0.05). Rescue analgesia in the PACU was required in 47.5% of patients in Group M and 10.0% in Group B (P < 0.001). The mean time to achieve VAS <3 was significantly shorter in Group B (11.00 ± 3.79 min) compared to Group M (16.00 ± 9.00 min) (P = 0.002). The requirement of antiemetic medication was lower in Group B (20.0%) than in Group M (42.5%) (P = 0.030). No adverse events were reported in either group.

Conclusion: Ultrasound-guided ACB provides superior post-operative analgesia, faster pain relief, and fewer side effects compared to intravenous morphine in patients undergoing knee arthroscopy.

Keywords: Adductor canal block, knee arthroscopy, post-operative analgesia, morphine, ultrasound-guided block.

Knee arthroscopy is among the common orthopedic procedures associated with moderate post-operative pain that can delay recovery, impair early mobilization, and increase opioid consumption in the immediate post-operative period. Effective analgesia that minimizes opioid exposure while providing rapid pain relief is, therefore, a cornerstone of enhanced recovery after surgery pathways for ambulatory and short-stay knee procedures [1]. Systemic opioids such as morphine remain widely used for perioperative analgesia because of their potent analgesic effects; however, opioid use is frequently accompanied by adverse effects – most notably nausea, vomiting, sedation, and respiratory depression – that can prolong post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) stay and reduce patient comfort. Strategies that reduce perioperative opioid requirements are therefore attractive for reducing these side effects and expediting recovery [2,3].

Regional, procedure-specific peripheral nerve blocks have gained popularity as opioid-sparing techniques after knee surgery. The adductor canal block (ACB) targets sensory branches in the mid-thigh and is designed to provide analgesia to the anteromedial knee while largely preserving quadriceps strength; this motor-sparing profile offers theoretical and practical advantages for early mobilization and fall risk reduction when compared with femoral nerve block (FNB). Several randomized trials and meta-analyses have shown that ACB provides comparable analgesia to FNB with better preservation of quadriceps function, and that incorporation of ACB into multimodal analgesia protocols can reduce opioid requirements after knee surgery [4,5]. Despite accumulating evidence in major knee surgery (arthroplasty and anterior cruciate ligament procedures), fewer high-quality studies have assessed the impact of ultrasound-guided ACB specifically on immediate PACU outcomes – such as time to satisfactory pain relief (VAS <3), rescue analgesic requirement, antiemetic need, and readiness for criteria-based discharge (CBD) – after ambulatory knee arthroscopy. Given the importance of early PACU throughput and patient comfort after day-case arthroscopy, directly comparing ultrasound-guided ACB with conventional intravenous morphine in this population is clinically relevant. This study, therefore, aimed to compare post-operative analgesic efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided ACB versus intravenous morphine in patients undergoing unilateral knee arthroscopy, and to evaluate whether procedure-specific analgesia shortens PACU stay and reduces opioid-related side effects [6].

Study site

The study was conducted in the PACU of the Department of Anesthesiology in a Hospital in India. All patients included in the study underwent surgery under the supervision of the same anesthesia team to ensure uniformity in perioperative management.

Study population

The study population comprised adult patients undergoing unilateral knee arthroscopy under general anesthesia in the operating room. Only those who fulfilled the eligibility criteria and provided written informed consent were enrolled in the study.

Study design

This randomized, interventional, and controlled study was designed to evaluate the post-operative analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided ACB compared to conventional intravenous morphine in patients undergoing unilateral knee arthroscopy. The secondary objectives included assessing the utility of the modified Aldrete scoring system for early, CBD from PACU compared with institutional time-based discharge (TBD) guidelines, as well as evaluating White’s fast-track score for identifying patients eligible for bypassing the high-dependency PACU. Patients were randomly allocated into two groups of 40 each. Randomization was performed using a computer-generated random sequence, and allocation was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes prepared by a member of the research team not involved in patient recruitment or clinical management. Group M received intravenous morphine (0.1 mg/kg body weight) before incision, whereas Group B received an ultrasound-guided ACB using 15 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine before extubation. A total of 80 patients were studied.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged between 18 and 65 years with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I or II of either sex, scheduled for unilateral knee arthroscopy under general anesthesia, were included. Exclusion criteria comprised patient refusal, ASA physical status III or IV, significant cardiac, hepatic, respiratory, or central nervous system disorders, psychiatric illness, intraoperative complications, pregnancy, requirement for post-operative intensive care, or administration of spinal or epidural anesthesia.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated to detect a 15-min difference in PACU discharge time between the two groups, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 20 min, a significance level (α) of 0.05, and a power (1–β) of 90%. The formula used was: n = (σ₁² + σ₂²) × (Z₁–α/2 + Z₁–β)²/(M₁ – M₂)²

Substituting the values (σ₁ = σ₂ = 20, Z₁–α/2 = 1.96, Z₁–β = 1.282, M₁ – M₂ = 15), the required sample size was calculated as 37 per group. To enhance statistical reliability, 40 patients were included in each group, giving a total sample of 80 patients.

Methodology

All participants underwent thorough pre-anesthetic evaluation and were subjected to standardized anesthetic techniques. In the operating room, baseline monitoring included heart rate, non-invasive blood pressure (BP), and oxygen saturation. Intravenous access was secured in all patients. General anesthesia was selected as the anesthetic technique in our institution because it allows better control of the airway and ventilation during arthroscopy, provides predictable intraoperative conditions, and avoids the potential for patient discomfort associated with tourniquet use under regional anesthesia. Anesthesia induction was achieved with fentanyl 2 µg/kg and propofol 2–2.5 mg/kg, followed by muscle relaxation with atracurium 0.5 mg/kg to facilitate insertion of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA). Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved using nitrous oxide and oxygen with sevoflurane (minimum alveolar concentration = 1), along with intermittent atracurium 0.1 mg/kg every 30 min. All patients received paracetamol 20 mg/kg and diclofenac 1.5 mg/kg for analgesia, and ondansetron 4 mg was administered 30 min before LMA removal. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg. Postoperatively, tramadol 50 mg was used as rescue analgesia for pain scores >3/10, and ondansetron 4 mg was administered for nausea or vomiting as required.

Ultrasound-guided ACB technique

In Group B, the ACB was performed after confirming the operative site. The patient was positioned supine with the knee slightly flexed and externally rotated (frog-leg position). Following aseptic preparation with 10% povidone-iodine, a high-frequency linear ultrasound probe was placed on the anterior thigh, midway between the inguinal crease and medial condyle. The femoral artery was identified beneath the sartorius muscle within the adductor canal. Using an in-plane lateral-to-medial approach, the needle was advanced under real-time ultrasound guidance to the adductor canal, and after negative aspiration, 1 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected to confirm proper spread. The remaining local anesthetic (total 15 mL) was injected incrementally in 5 mL aliquots, ensuring circumferential spread around the femoral artery within the canal.

Scoring systems and discharge criteria

White’s fast-track score was recorded intraoperatively before transferring the patient to the PACU to assess eligibility for direct transfer to a step-down recovery unit. In the PACU, nursing staff were trained on the study protocol and discharge criteria. Physiologic parameters – sedation, respiration, heart rate, mean BP, oxygen saturation, temperature, pain score (VAS <3), and nausea/vomiting score (<2) – were recorded every 10 minutes until discharge or up to 60 minutes as per institutional guidelines. The modified Aldrete score was documented every 10 min by trained PACU nurses until a score of 9 or above was achieved, defined as CBD time. Institutional policy mandated discharge at 60 min TBD. The mean CBD time was compared between the two groups and against the fixed TBD of 60 min. Any adverse events requiring medical or nursing intervention between CBD and TBD were also recorded. In addition, the actual discharge time (TBD plus non-clinical delays) was documented, and reasons for delay, such as unavailability of staff or ward beds, were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, whereas categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Data normality was tested before statistical analysis. An independent sample t-test was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

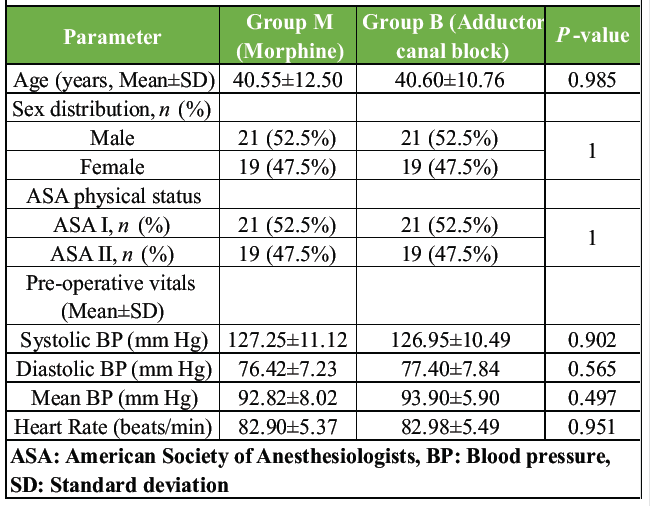

The demographic and baseline characteristics of both groups were comparable, indicating appropriate randomization and homogeneity between the study populations (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in mean age, gender distribution, ASA physical status, or pre-operative hemodynamic parameters, suggesting that both groups were similar before intervention. Such comparability ensures that the observed post-operative outcomes can be reliably attributed to the analgesic technique rather than baseline variability.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of study participants

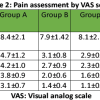

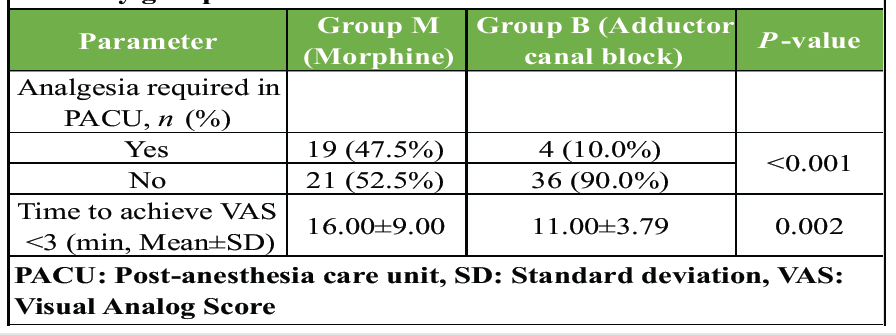

In the post-operative period, the ACB demonstrated superior analgesic efficacy compared to conventional intravenous morphine administration (Table 2). Patients in the block group exhibited significantly better pain control, as reflected by reduced analgesic requirements in the PACU and a shorter duration to achieve adequate pain relief (VAS < 3). These findings indicate that ACB provided more effective and faster post-operative analgesia following knee arthroscopy.

Table 2: Comparison of post-operative analgesic efficacy between the study groups

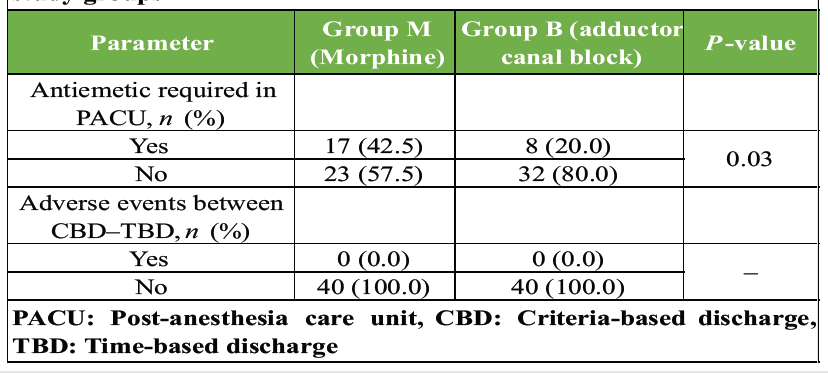

Regarding post-operative adverse effects, patients who received ACB experienced fewer side effects than those who received intravenous morphine (Table 3). The need for antiemetic medication was notably lower in the block group, and no adverse events were reported in either group during the recovery period. This highlights the favorable safety and tolerability profile of ACB compared to systemic opioid analgesia.

Table 3: Comparison of post-operative adverse effects between the study groups

This randomized, controlled study demonstrates that ultrasound-guided ACB provides superior post-operative analgesia compared with conventional intravenous morphine for patients undergoing unilateral knee arthroscopy. Patients who received ACB required substantially fewer rescue analgesic doses in the PACU and achieved satisfactory pain relief (VAS < 3) more rapidly than those who received systemic morphine (Table 2). These findings support the role of a procedure-specific, peripheral nerve block in improving immediate post-operative analgesia while reducing opioid exposure and its attendant side effects. The observed opioid-sparing effect and more rapid achievement of analgesic goals after ACB are consistent with prior clinical reports showing that ACB reduces early post-operative pain scores and opioid consumption after knee procedures. Single-shot or continuous ACB has repeatedly been associated with lower opioid requirements and improved early analgesia in studies of arthroscopic and major knee surgery, supporting our finding that ACB improves early PACU pain control compared with systemic opioids alone [7,8]. Lower requirement for antiemetic medication in the ACB group (Table 3) aligns with the expected reduction in opioid-related adverse effects when systemic opioid consumption is decreased. Several clinical series and randomized trials have reported fewer opioid-related side effects (nausea, vomiting, and sedation) when regional or opioid-sparing strategies are employed, reinforcing the practical benefit of ACB for improving patient comfort and potentially shortening PACU recovery needs [9]. Preserving motor function while providing effective sensory blockade is an important advantage of ACB compared with more proximal femoral nerve blockade; the motor-sparing property facilitates earlier mobilization and may reduce fall risk – an important consideration in ambulatory and short-stay knee surgery pathways. Although our study did not measure objective quadriceps strength, the improved pain control without excess adverse events (Table 3) and faster achievement of pain goals (Table 2) are compatible with the motor-sparing, analgesic profile reported for ACB in the literature [10,11]. The clinical implications of our results extend beyond analgesia alone. By reducing immediate rescue analgesia and antiemetic needs, ACB has the potential to enhance PACU efficiency and patient throughput. In our protocol we also evaluated readiness for CBD (modified Aldrete score) and fast-track eligibility (White’s score); while detailed logistics are outside the primary focus of the present manuscript, the analgesic advantages we observed (Table 2) are likely contributors to earlier achievement of discharge criteria and fewer opioid-related nursing interventions, which may translate into operational benefits for high-volume ambulatory services. This observation is supported by prior studies that linked reduced opioid consumption after ACB to improved early functional recovery and shorter post-operative observation requirements [1,8]. Strengths of this study include randomized allocation, standardized anesthetic care across groups, and objective PACU endpoints that are directly relevant to early post-operative recovery (rescue analgesic use, time to VAS <3, antiemetic requirement). Limitations include the single-center design and the fact that longer-term outcomes beyond the immediate PACU period (e.g., 24-h opioid consumption, functional recovery at home) were not captured in this analysis; additionally, quadriceps strength and standardized functional tests were not measured and would further contextualize motor-sparing benefits. Future studies could examine multimodal regimens combining ACB with other regional techniques or local infiltration to determine whether additional opioid-sparing or functional advantages are achievable in arthroscopic populations [12].

The findings of this study demonstrate that the ultrasound-guided ACB provides significantly better post-operative analgesia compared to conventional intravenous morphine in patients undergoing unilateral knee arthroscopy. Patients receiving the ACB required fewer rescue analgesic doses and achieved satisfactory pain relief more rapidly, indicating superior analgesic efficacy. Furthermore, the block was associated with a lower incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting, confirming a favorable safety and tolerability profile. As both groups were comparable in demographic and pre-operative characteristics, the observed differences can be attributed to the analgesic technique itself. Therefore, the ACB can be considered a safe, effective, and procedure-specific regional anesthesia technique that enhances post-operative recovery and patient comfort while minimizing opioid-related side effects in knee arthroscopy surgery.

Incorporating ultrasound-guided adductor canal block into post-operative pain management for knee arthroscopy significantly enhances pain relief, reduces the need for rescue analgesics, and minimizes nausea and vomiting associated with opioid use. This motor-sparing, procedure-specific regional technique improves patient comfort, facilitates early recovery, and aligns well with enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols for ambulatory knee procedures.

References

- 1. Xie Y, Sun Y, Lu Y. Effect of adductor canal block combined with local infiltration analgesia on postoperative pain of knee arthroscopy under general anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Ther 2023;12:543-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Remy C, Marret E, Bonnet F. Effects of acetaminophen on morphine side-effects and consumption after major surgery: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 2005;94:505-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Zhang Z, Li C, Xu L, Sun X, Lin X, Wei P, et al. Effect of opioid-free anesthesia on postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynecological surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 2024;14:1330250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kim DH, Lin Y, Goytizolo EA, Kahn RL, Maalouf DB, Manohar A, et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2014;120:540-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Wang D, Yang Y, Li Q, Tang SL, Zeng WN, Xu J, et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep 2017;7:40721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Hasabo EA, Assar A, Mahmoud MM, Abdalrahman HA, Ibrahim EA, Hasanin MA, et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for pain control after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101:e30110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Ramanathan A, Meena DS, Nagalingam N, Gopalakrishnan K. Comparative evaluation of analgesic efficacy of adductor canal block versus intravenous diclofenac in patients undergoing knee arthroscopic surgery. Anesth Essays Res 2021;15:157-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hanson NA, Allen CJ, Hostetter LS, Nagy R, Derby RE, Slee AE, et al. Continuous ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind trial. Anesth Analg 2014;118:1370-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Ali HM, Nour Eldin BM, Ahmed HA, Gobran RM, Heiba DE. Comparative study between continuous adductor canal block and intravenous morphine for postoperative analgesia in total knee arthroplasty. Ain Shams J Anesthesiol 2020;12:62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Jæger P, Zaric D, Fomsgaard JS, Hilsted KL, Bjerregaard J, Gyrn J, et al. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013;38:526-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Fan Chiang YH, Wang MT, Chan SM, Chen SY, Wang ML, Hou JD, et al. Motor-sparing effect of adductor canal block for knee analgesia: An updated review and a subgroup analysis of randomized controlled trials based on a corrected classification system. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11:210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. AbdelRady MM, Ali WN, Younes KT, Talaat EA, AboElfadl GM. Analgesic efficacy of single-shot adductor canal block with levobupivacaine and dexmedetomidine in total knee arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Egypt J Anaesth 2021;37:386-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]