Autologous tensor fascia lata interposition combined with complete extraperiosteal excision and early mobilization provides a reliable, low-recurrence method for restoring forearm rotation in proximal radioulnar synostosis.

Dr. Piyush Sharma, Department of Orthopaedics, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: piyush7133@gmail.com

Introduction: A debilitating side effect of comminuted elbow or forearm fractures and their surgical treatment is proximal radioulnar synostosis (PRUS), which is defined by heterotopic bone bridging between the radius and ulna and nearly total loss of forearm rotation. The standard treatment for established PRUS is surgical removal of the synostotic mass; nevertheless, unless a long-lasting interposition barrier is employed, recurrence persists as a threat. Autologous tensor fascia lata (TFL) grafting has been shown to restore rotation with minimal donor-site morbidity and serves as a biologic interposition.

Aim: Excision with TFL interposition for post-traumatic PRUS following proximal ulna plating: a comprehensive, critically updated review and original cohort experience with a focus on technique, functional results, recurrence, graft integration, heterotopic ossification (HO) prophylaxis, and rehabilitation plan.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective observational study examined a consecutive cohort treated between 2017 and 2024, demonstrating radiologic graft integration, low donor-site morbidity, uncommon recurrence, significant improvement in pronation–supination and functional scores, and confirming – consistent with larger series – the effectiveness of TFL interposition when combined with complete extraperiosteal excision, circumferential graft fixation, early controlled mobilization, and targeted HO prophylaxis.

Conclusion: Following proximal ulna fixation, excision combined with autologous TFL interposition is a dependable method of restoring rotation following PRUS. The establishment of standardized scheduling, graft selection, and preventive regimens requires multicenter prospective trials with prolonged follow-up.

Keywords: Proximal radioulnar synostosis, tensor fascia lata graft, heterotopic ossification, autologous interposition.

A fairly uncommon but substantially incapacitating consequence of high-energy elbow or forearm injuries and several surgical procedures is proximal radioulnar synostosis (PRUS). Heterotopic bone growth connecting the proximal radius and ulna is the pathognomonic lesion. This effectively eliminates forearm pronation and supination and significantly hinders daily living activities and many vocations [1,2,3]. Although rates are greater in some cohorts with severe soft-tissue disruption, the reported frequency varies depending on the injury pattern and care. According to recent data, PRUS occurs in a small percentage of patients following difficult periarticular fractures and osteosynthesis [1,3]. A permissive inflammatory and osteogenic milieu for heterotopic ossification (HO) and bridging synostosis can be fostered by a number of well-documented risk factors for PRUS, including severe soft-tissue injury, significant periarticular comminution, placement of fixation across the proximal radius/ulna, violation of the interosseous membrane, multiple operations or hardware revisions, prolonged immobilization, and concurrent traumatic brain injury [2,3,4,5]. The natural course of early HO varies; surgical excision is necessary once mature corticalized bone grows between the radius and ulna, as non-operative functional restoration is doubtful [2,4]. Due to the local osteogenic environment’s continued activity, surgical resection by itself has historically carried a significant risk of recurrence; in earlier series, reported recurrence rates approximated 20–30% in the absence of an interposition barrier [3,4,5]. Surgeons have employed perioperative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), interposition materials (autologous tissues such as muscle, fascia lata, or adipofascial flaps; and synthetic barriers such as silicone or polytetrafluoroethylene, and – in certain centers – localized low-dose radiation as HO prophylaxis to lessen re-ossification [6,7,8,9,10]. Autologous tensor fascia lata (TFL) is a popular alternative for biologic interposition in many contemporary series due to its tensile strength, thinness for contouring, superior biocompatibility, and documented minimal donor-site morbidity [4, 11, 12 ]. Together with careful extraperiosteal excision and focused rehabilitation, the well-known TFL case series and procedure reports show significant improvements in pronation-supination arcs and low rates of symptom recurrence [4,6]. This publication presents both evidence-based perioperative adjuncts and a practical surgical approach that maximizes lasting rotational healing by refining and combining our cohort experience (2017–2024) with the larger literature.

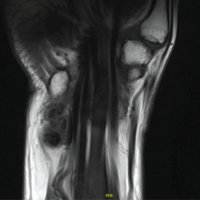

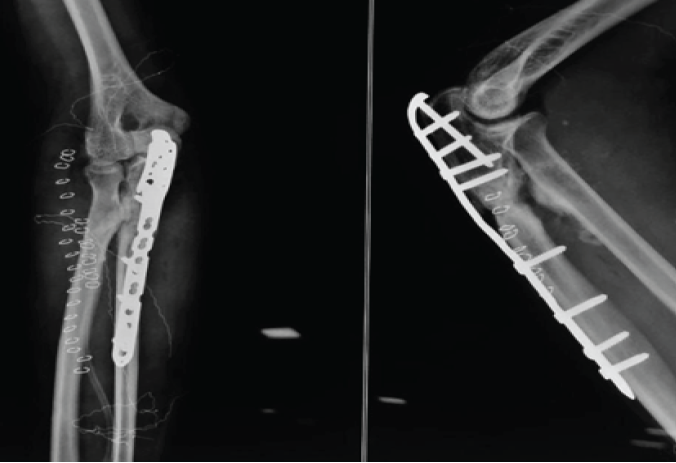

At a tertiary care center in East India, we conducted a retrospective observational study of five adult patients treated for post-traumatic PRUS after proximal ulna plating from 2017 to 2024. Ages 18–60, radiographically confirmed mature PRUS (Fig. 1), rotational limitation at least 12 weeks after index fixation (Fig. 2), and a minimum 12-month follow-up are requirements for inclusion. Congenital synostosis, persistent infection, or numerous ipsilateral upper-limb injuries that might complicate results were among the exclusion criteria.

Figure 1: Proximal radioulnar synostosis following 14 weeks of proximal ulnar plating.

Figure 2: Limitation of supination – pronation arc following 14 weeks of index fixation (right).

Pre-operative assessment

Patients underwent standardized clinical assessment (goniometric measurement of pronation and supination, flexion-extension range, and Mayo Elbow performance score [MEPS]). Computed tomography with 3-D reconstruction characterized the synostosis extent and guided planning for extraperiosteal excision.

Surgical technique

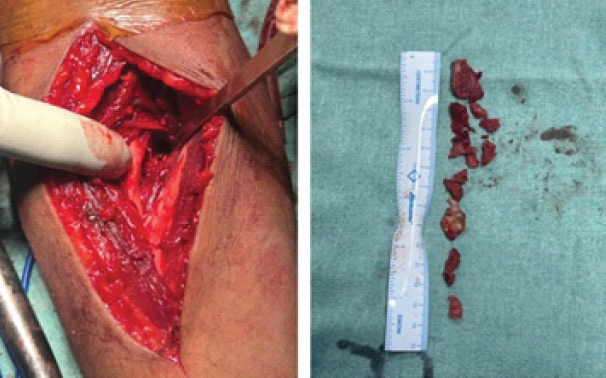

Under general anesthesia with a tourniquet, an anterior approach to the proximal forearm was used as the primary exposure to directly access the radioulnar synostosis and limit posterior soft-tissue disruption. When posterior bridging or limited anterior exposure prevented complete removal, a supplementary posterior incision was employed. The synostotic mass was removed extraperiosteally using a high-speed burr and rongeurs until normal radial and ulnar cortical anatomy was restored and full passive rotation achieved intraoperatively under fluoroscopy [3,8] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Operative photograph illustrating full excision of the synostotic mass with adequate clearance of the proximal radioulnar space.

Autologous TFL graft (approximately 4–6 cm square, tailored to defect) was harvested from the ipsilateral thigh through a small longitudinal incision, avoiding large muscle dissection. The graft was positioned circumferentially between radius and ulna and secured to periosteum and residual interosseous membrane remnants using interrupted absorbable sutures to create a stable biologic barrier that could accommodate rotation [4,11] (Fig. 4). Meticulous hemostasis, layered closure, suction drain placement, and perioperative antibiotics were routine.

Figure 4: Circumferentially placed tensor fascia lata graft following synostotic mass excision acting as a biological barrier.

HO prophylaxis and rehabilitation

Since there is still disagreement on the best way to prevent HO, treatment was tailored; radiotherapy was saved for a few high-risk cases after multidisciplinary discussion, and the majority of patients got 75 mg of indomethacin/day for 6 weeks unless it was contraindicated [13,14,15]. No strict immobilization of rotation was employed; early passive mobilization started within 48 h and progressed to active-assisted motion in a painless arc. Under supervision, progressive strengthening began about 6 weeks ago.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes were pronation–supination arc and MEPS at final follow-up. Secondary outcomes included radiographic recurrence of bridging HO, graft-related complications, donor-site morbidity, and return-to-work/activity.

Between 2017 and 2024, five consecutive patients met the inclusion criteria (mean age 42 years; four male, one female). Mechanism of index injury included high-energy trauma in most cases. The interval from index fixation to synostosis excision ranged from 3 to 9 months (median ~5 months). Mean clinical follow-up was 14 months (range 12–24 months).

Range of motion and functional outcome (Table 1)

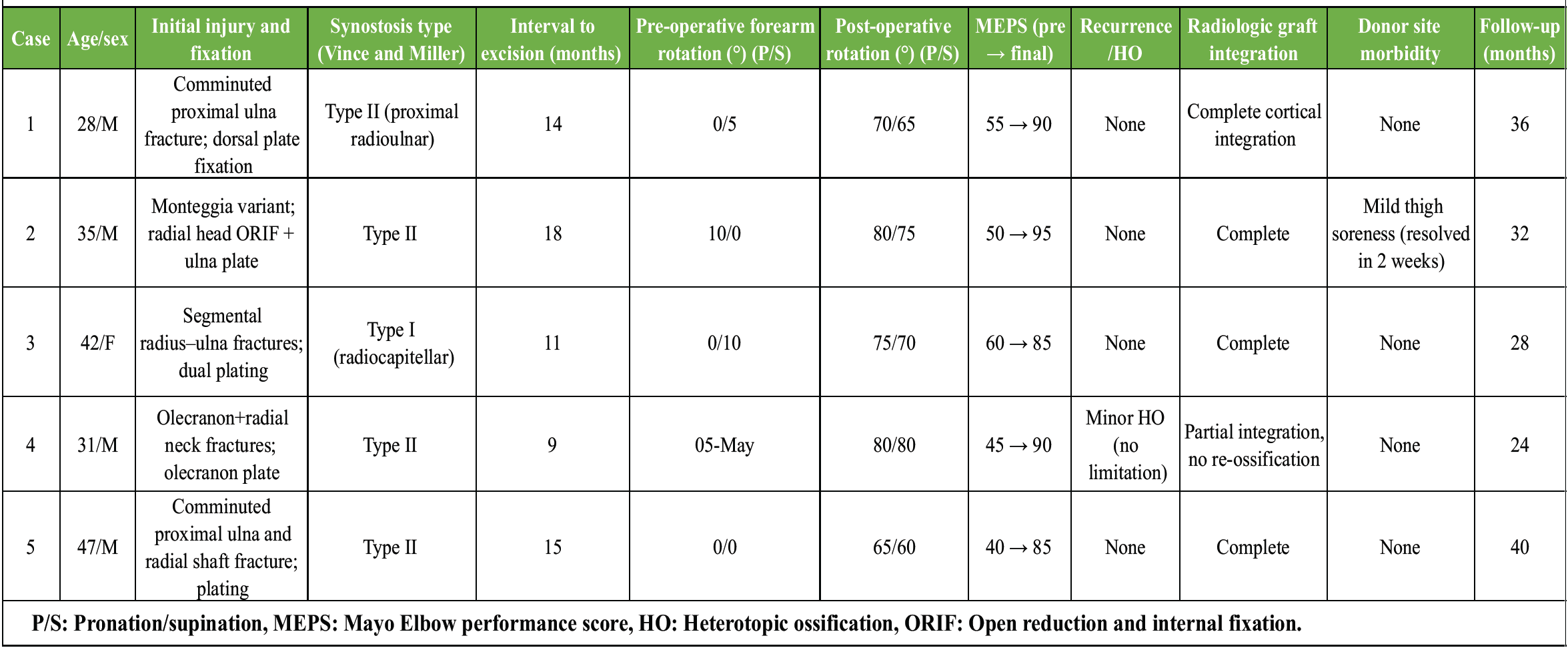

Table 1: Clinical and functional outcomes following excision of post-traumatic radioulnar synostosis with TFL interposition

Pre-operative mean pronation–supination arc was severely limited (mean 12°). After TFL interposition and rehabilitation, the mean pronation–supination arc increased to 70° (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). Elbow flexion-extension remained preserved in all cases (0–130°). Median MEPS improved from 66 preoperatively to 93 at final follow-up (P < 0.01). All patients returned to pre-injury or similar occupational activities within 3 months of surgery.

Figure 5: Post-operative restoration of pronation-supination arc up to 70° (Right).

Radiologic outcome and recurrence

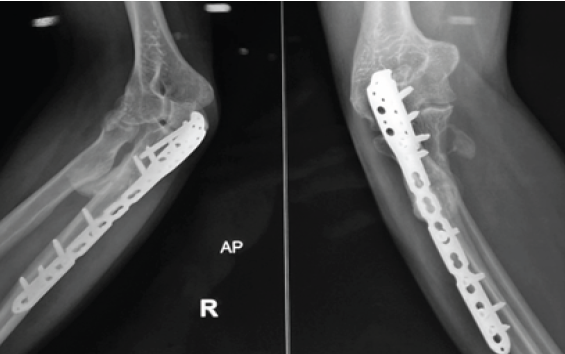

Immediate post-operative radiographs confirmed removal of synostotic bone and interposition placement (Fig. 6). At last radiographic follow-up, four patients demonstrated no re-ossification; one patient developed minimal, asymptomatic ossific recurrence abutting the graft but without functional limitation.

Figure 6: Immediate post-operative radiograph with removal of synostotic bone and interpositional placement.

Complications

There were no neurovascular injuries, deep infections, or graft failures. Donor-site morbidity was minimal: One patient reported transient thigh soreness for 2 weeks; no seromas or wound complications occurred.

These results align with contemporary reports that show meaningful restoration of rotation and low symptomatic recurrence with TFL interposition when combined with meticulous excision and structured rehabilitation [4,6,11].

Restoring forearm rotation after mature PRUS remains a technically demanding challenge in upper-extremity reconstruction. Evidence from both the present cohort and established literature consistently reinforces three foundational principles for durable correction: meticulous extraperiosteal excision of the synostotic bridge, use of a stable interposition barrier – most reliably achieved with autologous TFL – and early, protected mobilization supported by rational HO prophylaxis [3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 16 ]. Autologous TFL offers a uniquely advantageous profile: It is thin yet robust, easily contoured to the interosseous gap, biologically compatible, and capable of being secured circumferentially to maintain a lasting physical separation between the radius and ulna [4]. Classic TFL series and modern reviews uniformly demonstrate significant and sustained gains in rotational arcs with low recurrence, underscoring that surgical precision is the primary determinant of success [4,6,11]. Synthetic interposition materials may reduce recurrence but lack biological incorporation and are associated with foreign-body reactions and potential migration, limiting their long-term reliability [10]. Recurrence after excision reflects persistent osteogenic drive or incomplete resection. Although NSAIDs such as indomethacin remain widely used, randomized studies report variable efficacy in elbow trauma, and meta-analytic conclusions regarding pharmacologic prophylaxis remain mixed [13,14,15]. Radiotherapy offers proven reduction in HO risk in select orthopedic settings but is constrained by logistical, radiation-related, and resource considerations, restricting use to carefully selected high-risk cases [14, 15 , 16]. These findings argue for an individualized prophylaxis strategy that incorporates injury severity, surgical burden, and neurological comorbidities such as traumatic brain injury. Several technical refinements enhance outcomes: Performing a true extraperiosteal excision, utilizing an anterior approach when feasible to minimize posterior scarring, extending posteriorly only when dense bridging demands it, removing all residual osteogenic debris, securing hemostasis, and ensuring circumferential fixation of the TFL graft to avoid displacement – an approach correlated with lower recurrence in comparative series [3,4,8,11]. Early gentle rotation facilitates graft–tissue conformity and reduces adhesion formation, while avoiding painful or forceful manipulation that risks graft instability or renewed HO stimulation [17, 18 ,19 ]. A structured strengthening program initiated at 6 weeks reliably restores functional rotational strength without jeopardizing the interposition. Although limited by its small retrospective design, this study aligns with a growing body of evidence supporting autologous TFL interposition as a dependable biologic solution for PRUS, offering meaningful restoration of rotation with minimal donor morbidity and low recurrence. Future multicenter prospective studies should compare interposition options head-to-head, delineate optimal HO prophylaxis protocols, and evaluate long-term outcomes to standardize care across institutions.

Although rare, PRUS following proximal ulna plating is functionally incapacitating. In modern series, consistent restoration of forearm rotation, low symptomatic recurrence, and minimal donor-site morbidity are achieved through complete extraperiosteal excision, autologous TFL interposition, careful surgical technique, selective HO prophylaxis, and early supervised rehabilitation. Even while small cohorts show promising effects, prospective multicenter trials with standardized procedures are required to improve graft selection, prophylactic algorithms, and scheduling for long-lasting, broadly applicable results.

Complete extraperiosteal excision combined with circumferential autologous TFL interposition reliably restores forearm rotation and minimizes recurrence in PRUS, offering a dependable, biologic, and low-morbidity solution when paired with early mobilization and selective HO prophylaxis.

References

- 1. Dohn P, Khiami F, Rolland E, Goubier JN. Adult post-traumatic radioulnar synostosis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012;98:709-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Failla JM, Amadio PC, Morrey BF. Post-traumatic proximal radio-ulnar synostosis. Results of surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989;71:1208-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Jupiter JB, Ring D. Operative treatment of post-traumatic proximal radioulnar synostosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:248-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Friedrich JB, Hanel DP, Chilcote H, Katolik LI. The use of tensor fascia lata interposition grafts for the treatment of posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis. J Hand Surg Am 2006;31:785-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kamineni S, Maritz NG, Morrey BF. Proximal radial resection for posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis: A new technique to improve forearm rotation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:745-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Giannicola G, Spinello P, Villani C, Cinotti G. Post-traumatic proximal radioulnar synostosis: Results of surgical treatment and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020;29:329-39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Bergeron SG, Desy NM, Bernstein M, Harvey EJ. Management of posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:450-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Cullen JP, Pellegrini VD Jr., Miller RJ, Jones JA. Treatment of traumatic radioulnar synostosis by excision and postoperative low-dose irradiation. J Hand Surg Am 1994;19:394-401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Osterman AL, Lee SK, Riley SA. Optimal management of post-traumatic radioulnar synostosis. Orthop Res Rev 2017;9:105-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Proubasta IR, Lluch A. Proximal radio-ulnar synostosis treated by interpositional silicone arthroplasty. A Case report. Int Orthop 1995;19:242-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Azeem MA, Alhojailan K, Awad M, Khaja AF. Post-traumatic proximal radioulnar synostosis: A retrospective case series. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2022;31:1595-602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Kontokostopoulos AP, Evangelopoulos DS, Korres DS. Heterotopic ossification around the elbow revisited. EFORT Open Rev 2023;8:957-68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Atwan Y, Abdulla I, Grewal R, Faber KJ, King GJ, Athwal GS. Indomethacin for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis following surgical treatment of elbow trauma: A randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2023;32:1242-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Popovic M, Agarwal A, Zhang L, Yip C, Kreder HJ, Nousiainen MT, et al. Radiotherapy for the prophylaxis of heterotopic ossification: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Radiother Oncol 2014;113:10-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Milakovic M, Popovic M, Raman S, Tsao M, Lam H, Chow E. Radiotherapy for the prophylaxis of heterotopic ossification: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiother Oncol 2015;116:4-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Meyers C, Lisiecki J, Miller S, Sorkin M, Hollenbeck ST, Levin LS, et al. Heterotopic ossification: A comprehensive review. J Orthop Res. 2019;37:1475–148517. Xu Y, Huang S, He H, He J, Chen Y, Hou Z, et al. Heterotopic ossification: Clinical features, basic science and current management strategies. J Transl Med. 2022;20:141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Bell SN, Benger D. Management of radioulnar synostosis with excision and anconeus interposition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(6):621–624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Wen L, Chen C, Deng Y, Chen G. Effectiveness of indomethacin in preventing heterotopic ossification: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res 2024;19:589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]