Single-stage arthroscopic minced cartilage implantation is a promising and viable option for the management of cartilage defects in the knee joint.

Dr. Tejaswini Phadnis, Department of Physiotherapy, YMT College of Physiotherapy, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dr.tejaswiniphadnis@gmail.com

Introduction: Autologous minced cartilage implantation (MCI) is an emerging single-stage technique for treating cartilage defects of the knee joint. This retrospective study evaluates the functional outcomes and safety of autologous MCI in patients with focal cartilage defects in the knee.

Materials and Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on five patients who underwent autologous MCI for International Cartilage Repair Society Grade 3 and 4 cartilage defects of the knee between 2022 and 2024. Autologous MCI involved harvesting autologous cartilage from the defect margins, mincing it, and implanting it into the lesion in a single procedure. Patient records were reviewed for demographic data, surgical details, and functional outcome scoring metrics preoperatively and 12 months post-surgery. Primary outcomes were assessed using the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score-12, Tegner Activity Scale and Visual Analog Scale.

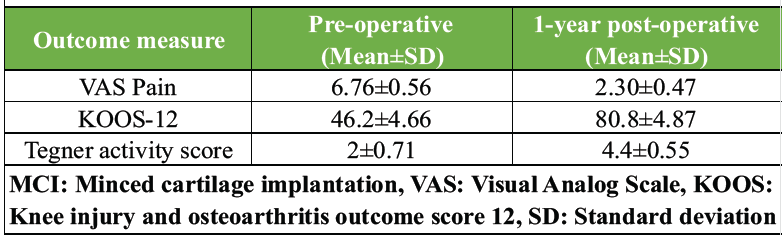

Results: Significant improvement in the functional scores was noted at the end of 1 year. The mean Visual Analog Scale pain score decreased from 6.76 ± 0.56 preoperatively to 2.30 ± 0.47 at 1 year, indicating substantial pain reduction. The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score 12 improved significantly from 46.2 ± 4.66 preoperatively to 80.8 ± 4.87 at 12 months follow-up. The Tegner Activity Score improved from 2 ± 0.71 to 4.4 ± 0.55 within the same time period, with most patients returning to moderate recreational activities.

Conclusion: This retrospective study demonstrates that autologous MCI is a safe and effective treatment for knee cartilage defects, yielding sustained functional improvements over a 1-year period. Despite the retrospective design, these findings support autologous MCI as a viable alternative to existing cartilage repair techniques. Prospective, randomized trials are needed to validate these results and compare autologous MCI with other treatment modalities.

Keywords: Autologous minced cartilage implantation, knee joint, cartilage defects, retrospective study.

Articular cartilage defects in the knee are being detected with increasing frequency due to the greater utilisation and enhanced diagnostic capabilities of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The improved accuracy and resolution of newer MRI machines have led to the identification of these lesions at earlier stages and in a larger patient population [1]. It is a well-established biological principle that, unlike many other tissues in the human body, articular cartilage defects in adults do not possess the inherent capacity for spontaneous healing post-puberty [2]. The typical natural history of these untreated defects involves a gradual progression in both diameter and depth, often leading to further deterioration of the joint surface and the onset of symptomatic complaints [3]. Consequently, there has been a growing impetus in orthopedic surgery toward the development and refinement of operative cartilage restoration techniques, with a diverse array of procedures now being employed to address these challenging clinical scenarios [4].

The primary objective underpinning any cartilage repair procedure is to facilitate the regeneration of the highest possible quality tissue within the defect. It is widely hypothesized that the quality of the regenerated tissue will directly correlate with improved clinical outcomes for patients, enabling a successful return to sporting activities and ensuring long-term durability of the repair [1]. Among the various techniques that have been developed, autologous minced cartilage implantation (MCI) has emerged as a relatively straightforward and cost-effective surgical option for transplanting a patient’s own cartilage fragments into the defect site in a single-step procedure [5]. MCI can be considered for the treatment of both small and large cartilage lesions, as well as for osteochondral lesions, which involve damage to both the cartilage and the underlying bone [1]. Furthermore, as it is a purely autologous approach, utilising the patient’s own tissue, it circumvents a significant portion of the regulatory oversight processes associated with other cell-based therapies, potentially allowing for more widespread clinical adoption without such limitations [6]. The MCI technique is currently garnering significant interest among surgeons globally due to several key attributes, including its rather simple surgical technique, its nature as a single-step procedure, its strong biologic potential, and its relatively high cost-effectiveness compared to more complex cell-based therapies [7]. This single-stage characteristic offers logistical advantages and potentially reduces healthcare-related costs by eliminating the need for a separate biopsy harvesting procedure and subsequent ex vivo cell culture in a laboratory under strict regulations, a major limitation associated with two-stage autologous MCI [5,8]. While short-term outcomes reported in the literature have been promising, with improvements in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), pain reduction, mid and long-term results are still needed to fully understand the durability of the repaired tissue[5,9,10,11].

A retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the outcomes of autologous MCI for chondral defects in the knee. Records of patients with cartilage lesions in the knee from a single orthopaedic centre between 2022 and 2024 treated with arthroscopic MCI using the AutoCart system (Arthrex) were reviewed. Data was collected on patient demographics, defect characteristics (size, location), surgical details (cartilage harvest site) and clinical outcomes (Visual Analog Scale [VAS] for pain, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score 12 [KOOS-12] and the Tegner Activity Scale [TAS].

Inclusion criteria

- Patients between the ages 18–50

- International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) grade three or four cartilage injury

- No prior arthroscopic procedure

- No osteoarthritic changes in the knee joint (less than Kellgren Lawrence grade two)

- Normal mechanical alignment of the lower limb

- Minimum follow-up period of 1 year

Exclusion criteria

- Patients below the age of 18 and above the age of 50

- ICRS grade less than three

- Prior arthroscopic procedures done

- Abnormal lower limb alignment

- Osteoarthritic changes in the knee joint (greater than Kellgren Lawrence grade two)

- Patients with symptoms in both knees

Surgical procedure

We initiated the arthroscopic autologous MCI technique with a diagnostic arthroscopy to assess the cartilage defect. Healthy cartilage was then arthroscopically harvested from the defect using a soft tissue shaver connected to an autologous tissue collector (GraftNet: Arthrex), ensuring minimal enlargement of the defect after preparation. The calcified layer was removed, but subchondral drilling was not performed. The harvested cartilage was minced into small fragments, resulting in a paste-like consistency. Minced cartilage was then mixed with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in a 1:3 ratio. The resulting mixture was loaded into an applicator. Autologous thrombin was generated from additional PRP using a specific device (Thrombinator: Arthrex). After thoroughly drying the joint, the defect was filled with the cartilage-PRP mixture using the applicator. Following a short waiting period, the knee joint was moved through a range of motion to confirm graft fixation over the chondral defect (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4).

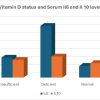

Figure 1: Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging showing cartilage lesion of the medial femoral condyle.

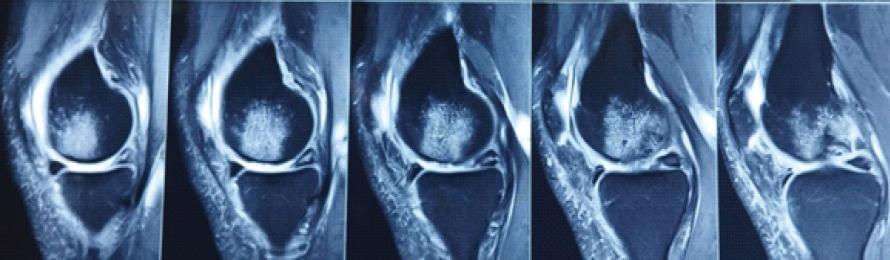

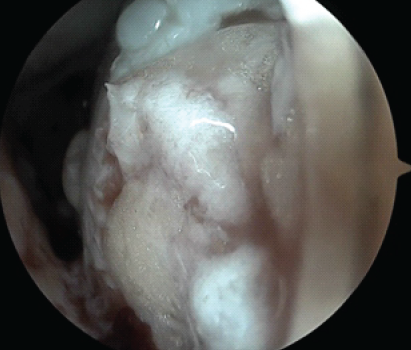

Figure 2: Arthroscopic image showing cartilage defect on the medial femoral condyle.

Figure 3: Arthroscopic image of the medial femoral condyle after delivery of the minced cartilage into the cartilage defect.

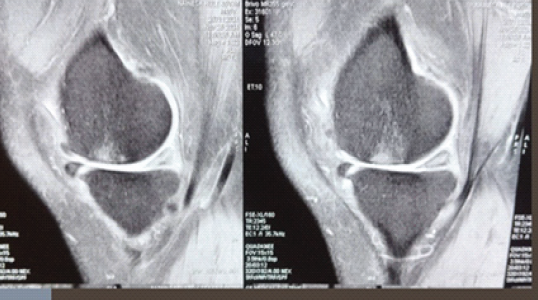

Figure 4: Post-operative magnetic resonance imaging 1 year after minced cartilage implantation.

PROMs

Patient-reported outcome measures included the VAS, KOOS-12 and TAS. These PROMs were obtained preoperatively and after a period of 12 months.

Rehabilitation

Postoperatively, patients were immobilized using a long knee brace for 3 days, following which static strengthening exercises were started along with passive and active assisted range of motion exercises as tolerated. Partial weight-bearing walking was encouraged with the knee held in extension, while full weight-bearing was restricted for a period of 6 weeks.

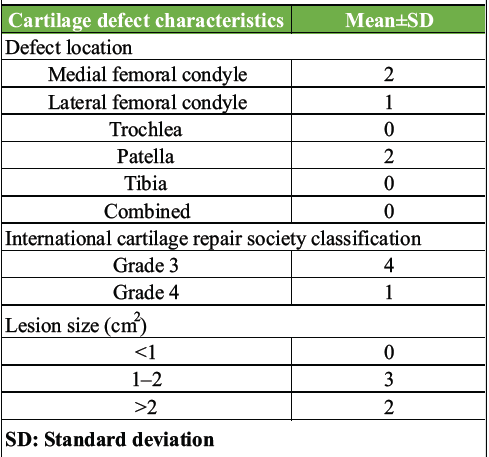

In this retrospective study of five patients who underwent autologous MCI for knee cartilage defects, significant improvements in pain, function, and activity levels were observed at 1-year follow-up. Patient 1, a 36-year-old male, had a 1.2 cm2 cartilage defect in the medial femoral condyle, which was ICRS Grade 3. Patient 2, a 28-year-old female, had a 2.2 cm2 cartilage defect in the lateral condyle of femur, which was ICRS Grade 4. Patient 3, a 35-year-old male, had a 1.7 cm2 defect on the patella of ICRS Grade 3. Patient 4, a 29-year-old female, had a 2.1 cm2 defect in her cartilage located on the medial femoral condyle, which was of ICRS Grade 3. Patient 5, a 38-year-old male, had a 1.3 cm2 cartilage defect on the patella of ICRS Grade 3. The cohort comprised 60% males and 40% females with a mean age of 33.2 ± 4.41 years. Defects were located in the medial femoral condyle (40%), patella (40%) and the lateral femoral condyle (20%), with 60% having defect sizes between 1 and 2 cm2 and 40% >2 cm2. ICRS grading showed 80% Grade three and 20% Grade four lesions. The mean Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score decreased from 6.76 ± 0.56 preoperatively to 2.30 ± 0.47 at 1 year, indicating substantial pain reduction. The KOOS-12 improved significantly from 46.2 ± 4.66 preoperatively to 80.8 ± 4.87 at 12 months follow-up. The Tegner Activity Score improved from 2 ± 0.71 to 4.4 ± 0.55, with most patients returning to moderate recreational activities.

One patient reported knee stiffness postoperatively. No other complications were noted (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1: Cartilage defect characteristics

Table 2: Mean functional scores pre- and post-MCI (1-year follow-up)

These findings are supported by a systematic review done by et al. [8], which shows that clinical research has demonstrated sustainable improvement in patient-reported outcome scores with minimal adverse events in patients undergoing single-stage procedures at 24 and 60 months follow-up. This review also highlighted the potential cost-effectiveness of single-stage procedures like MCI. In a study by Runer et al. [9] with a mean follow-up of 65.5 ± 4.1 months, reported on 34 patients treated with MCI for chondral and osteochondral lesions. This study found that the Numeric Analogue Scale (NAS) for pain significantly decreased from a median of seven preoperatively to two postoperatively. Similarly, NAS for knee function improved from a median of seven to three after 5 years. The patients also reported satisfactory Lysholm scores (76.5 ± 12.5) and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scores (71.6 ± 14.8) at the final follow-up. The study concluded that MCI demonstrated good patient-reported outcomes, low complication rates, and graft longevity at mid-term follow-up. In another study by Schneider et al. [10] with a 2-year follow-up of 62 patients who underwent arthroscopic MCI using the AutoCart system showed significant improvements in PROMs. The total KOOS score significantly improved from 62.4 ± 13.1 at baseline to 74.4 ± 15.9 at 24 months. Similar improvements were observed in VAS and WOMAC scores. The authors concluded that MCI demonstrated satisfying 2-year outcomes with increased PROM scores and that regenerated tissue quality on MRI was comparable to other cartilage repair methods. In a study conducted by Wodzig et al. [11], they noted that there was improvement in the VAS, KOOS and IKDC scores at 12 months follow-up. This data indicates that MCI is a promising and viable option for the treatment of cartilage lesions in the knee. A further study conducted by Massen et al. [12] reporting 2-year outcomes in 27 patients treated with a second-generation MCI technique found a significant decrease in pain and improvement in knee function on the NAS score. However, it is also noted that while these mid-term results are promising, more comparative trials with longer follow-up are needed to further define the benefits and long-term durability of MCI.

At the end of our study, we conclude that autologous MCI shows promising results for the treatment of chondral defects in the knee. However, more research with a prospective design, larger sample size and follow-up period is needed to further verify the efficacy and safety of this procedure.

As arthroscopy surgeons, cartilage defects are a frequent occurrence in patients. Minced cartilage implantation has demonstrated significant potential in managing this condition, as it is a single-stage procedure that yields favorable functional outcomes and is associated with low complication rates.

References

- 1. Salzmann GM, Ossendorff R, Gilat R, Cole BJ. Autologous minced cartilage implantation for treatment of chondral and osteochondral lesions in the knee joint: An overview. Cartilage 2021;13:1124S-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Ossendorff R, Walter SG, Schildberg FA, Spang J, Obudzinski S, Preiss S, et al. Biologic principles of minced cartilage implantation: A narrative review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023;143:3259-69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Richter DL, Schenck RC Jr., Wascher DC, Treme G. Knee articular cartilage repair and restoration techniques: A review of the literature. Sports Health 2016;8:153-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Salzmann GM, Calek AK, Preiss S. Second-generation autologous minced cartilage repair technique. Arthrosc Tech 2017;6:e127-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Frodl A, Siegel M, Fuchs A, Wagner FC, Schmal H, Izadpanah K, et al. Minced cartilage is a one-step cartilage repair procedure for small defects in the knee-a systematic-review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med 2022;12:1923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. McCormick F, Yanke A, Provencher MT, Cole BJ. Minced articular cartilage–basic science, surgical technique, and clinical application. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2008;16:217-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Jos S, Vijayakumar V, Paulose B, Benny K, James A. Arthroscopic autologous minced cartilage implantation for one stage reconstruction of chondral lesion of the femoral condyle of the knee joint: Surgical decision making and short term outcome with review of literature- case report. J Orthop Rep 2025;4:100414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Dasari SP, Jawanda H, Mameri ES, Fortier LM, Polce EM, Kerzner B, et al. Single-stage autologous cartilage repair results in positive patient-reported outcomes for chondral lesions of the knee: A systematic review. J ISAKOS 2023;8:372-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Runer A, Ossendorff R, Öttl F, Stadelmann VA, Schneider S, Preiss S, et al. Autologous minced cartilage repair for chondral and osteochondral lesions of the knee joint demonstrates good postoperative outcomes and low reoperation rates at minimum five-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2023;31:4977-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Schneider S, Ossendorff R, Walter SG, Berger M, Endler C, Kaiser R, et al. Arthroscopic autologous minced cartilage implantation of cartilage defects in the knee: A 2-year follow-up of 62 patients. Orthop J Sports Med 2024;12:23259671241297970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Wodzig MH, Peters MJ, Emanuel KS, Van Hugten PP, Wijnen W, Jutten LM, et al. Minced autologous chondral fragments with fibrin glue as a simple promising one-step cartilage repair procedure: A clinical and MRI study at 12-month follow-up. Cartilage 2022;13:19-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Massen FK, Inauen CR, Harder LP, Runer A, Preiss S, Salzmann GM. One-step autologous minced cartilage procedure for the treatment of knee joint chondral and osteochondral lesions: A series of 27 patients with 2-year follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med 2019;7:2325967119853773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]