TENS is a safe, physiological, and efficient method for treating pediatric femoral shaft fractures, providing early mobilization, rapid healing, and minimal complications.

Dr. Mohd Adnan, Department of Orthopedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: abdi.mohdadnan2011@gmail.com

Introduction: Femoral shaft fractures represent approximately 1.6% of all bone injuries in children. Angulation, malrotation, and shortening are not always corrected effectively by conservative methods. These also depend on fracture anatomy: Stable (transverse and oblique) and unstable (spiral and comminuted). In recent years, flexible intramedullary nailing has gained wide acceptance for treating pediatric and adolescent femoral fractures because of the lower chance of iatrogenic infection and the prohibitive cost of in-hospital traction and Spica cast care. The present prospective study was designed to evaluate outcomes of stable and unstable diaphyseal femoral fractures in children aged 5–15 years using the titanium elastic nailing (TEN) system. Both subjective and objective parameters were assessed, including pain relief, patient comfort, early mobilization, surgical technique, radiographic union, progression of weight bearing, and post-operative complications.

Materials and Methods: Children and adolescents between 5 and 15 years of age with femoral shaft fractures admitted to Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, and fulfilling the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. All selected patients were treated using TEN for fracture fixation. Post-operative follow-up was conducted over 6 months at 6, 12, and 24 weeks. A total of 90 cases were analyzed, comprising 45 stable and 45 unstable fractures. The results showed favorable outcomes in stable fracture cases, whereas among unstable fractures, three patients developed angular deformities and one patient had limb shortening.

Conclusion: Titanium elastic nails lead to rapid fracture union by preservation of fracture hematoma and limited soft tissue exposure. It also helps in preventing damage to the physis. A stable pediatric femoral diaphyseal fracture has very good results with minimal complications. Unstable pediatric femoral diaphyseal fractures, though they had good results in most cases, had angular deformities in 3 cases, and 1 case developed limb shortening. Based on the findings of this study, alternative surgical methods may be more suitable for severely unstable pediatric femoral shaft fractures. Overall, TEN should be regarded as the preferred treatment option for femoral diaphyseal fractures in children aged 5–15 years.

Keywords: Elastic nail, pediatric femur fracture, limb length discrepancy, Flynn’s criteria.

Femoral shaft fractures represent one of the most frequent major orthopedic injuries encountered in pediatric patients and are commonly managed by orthopedic surgeons in routine practice. They are also the leading pediatric orthopedic injuries requiring hospital admission. These fractures constitute approximately 1.6% of all fractures in children and occur more often in males than in females [1]. Although femoral shaft fractures in children result in significant short-term functional impairment, they are typically managed successfully with minimal long-term complications. Several treatment modalities are available for pediatric femur fractures, including spica casting, traction followed by spica casting, open reduction and internal fixation, external fixation, and intramedullary nailing [2,3,4,5]. Conventionally, pediatric femoral shaft fractures were managed with traction followed by casting, and these injuries were among the leading causes of prolonged hospital stays for a single diagnosis. However, casting was associated with several complications, including pressure sores, difficulties with perineal hygiene, and loss of fracture alignment. Over the past two decades, there has been a significant shift toward surgical stabilization of femoral shaft fractures in school-aged children. Techniques, such as flexible intramedullary nailing, dynamic compression plating, external fixation, and, more recently, submuscular plating have gained popularity. These surgical advances have reduced early functional disability in children and significantly lessened the caregiving burden on families during the recovery period [6]. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN) is widely used in the management of pediatric femoral fractures and offers several advantages over alternative treatment techniques. The method was first described in 1982 by the Nancy group in France and was originally termed Embrochage Centro Médullaire Élastique Stable [7]. It has begun to be preferred because of the small incision, less blood loss, no damage to the epiphyseal of the trochanter major, and increased interest in surgery. In older children, femoral shaft fractures are rarely the result of abuse, as their bones are typically strong enough to withstand significant direct forces and rotational stress without fracturing. In this age group, such fractures most commonly occur due to high-energy mechanisms, including sports-related injuries and motor vehicle accidents [8]. Flexible intramedullary nailing has become the preferred treatment modality due to its minimal soft tissue disruption, preservation of the fracture hematoma, and avoidance of physeal injury. However, the outcome of this technique largely depends on the fracture pattern, particularly whether the fracture is stable or unstable [9].

Patients having a history of trauma and pain in the thigh with X-ray showing a fracture of the femur, aged between 5 and 15 years, who are admitted to Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, were selected for the study after obtaining their consent. 45 stable (transverse and oblique) and 45 unstable (spiral and multifragmentary) cases were studied and compared.

Inclusion criteria

The patient with a fracture of the shaft of the femur unilaterally or bilaterally. Aged between 5 and 15 years.

Exclusion criteria

Patients aged above 15 years. Patients with open fractures, pathological fractures, metabolic bone disease, head trauma, and neurological.

Deficits were excluded from the study.

Pre-operative care

Upon admission, each patient’s general condition was evaluated with particular attention to signs of hypovolemia and the presence of associated orthopedic or systemic injuries, and appropriate resuscitative measures were initiated as required. All patients were immobilized using a Thomas splint and were administered analgesics through intramuscular injections along with intravenous antibiotics. A comprehensive clinical assessment was conducted, including a detailed history covering age, sex, occupation, mechanism of injury, and any previous or associated medical conditions. Routine laboratory investigations were performed for all patients. Clinical and radiological evaluations were carried out to identify any additional injuries. Radiographic assessment included anteroposterior and lateral views of the affected limb. Intravenous cephalosporin antibiotics were administered to all patients, and surgical intervention was undertaken at the earliest opportunity once pediatric clearance for anesthesia was obtained.

Surgical technique

Pre-operatively, the appropriate nail size was determined by measuring the inner cortical diameter of the femur, dividing it by two, and subtracting one. Using a bone awl, medial and lateral entry points were created in the distal femur just above the epiphysis under image intensifier guidance. Two nails of equal size were inserted sequentially up to the fracture site and then advanced simultaneously across the fracture after achieving reduction. The nails were positioned just short of the proximal femoral physis, cut, bent, and buried beneath the soft tissue. Post-operatively, hip and knee mobilization, quadriceps strengthening exercises, and non-weight-bearing ambulation using crutches were initiated as pain allowed.

Follow-up

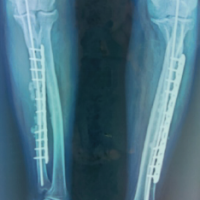

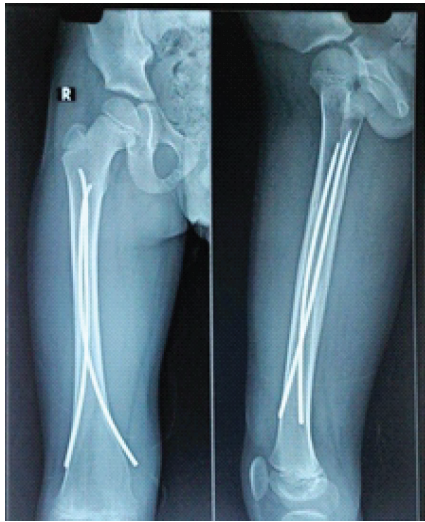

Post-operatively, patients were followed for 6 months with evaluations at 6, 12, and 24 weeks. Partial weight bearing was started at 6 weeks and gradually increased to full weight bearing once radiographic evidence of fracture union was observed on anteroposterior and lateral X-rays. During follow-up, patients were assessed for the time to fracture union, the occurrence of complications, such as superficial or deep infections, implant prominence or migration, fracture angulation, loss of reduction, fracture collapse, limb shortening, and range of motion. In addition, at the past follow-up, an orthoroentgenogram (scanogram) was performed to check whether there was limb length discrepancy (LLD). Pain, malalignment, LLD, and complications were reported and classified according to Flynn’s criteria. Ethical clearance was taken from the institute. In the image, Fig. 1 is showing mid 1/3rd shaft of femur fracture. Fig. 2 & 3 is showing immediate post-operative X-ray. Fig. 4 shows 2 years of follow-up, and Fig. 5 shows the X-ray after hardware extraction.

Figure 1: Immediate after trauma.

Figure 2: X-ray on thomas splint.

Figure 3: Immediate post-X-ray.

Figure 4: After 2 years of follow-up.

Figure 5: After implant removal.

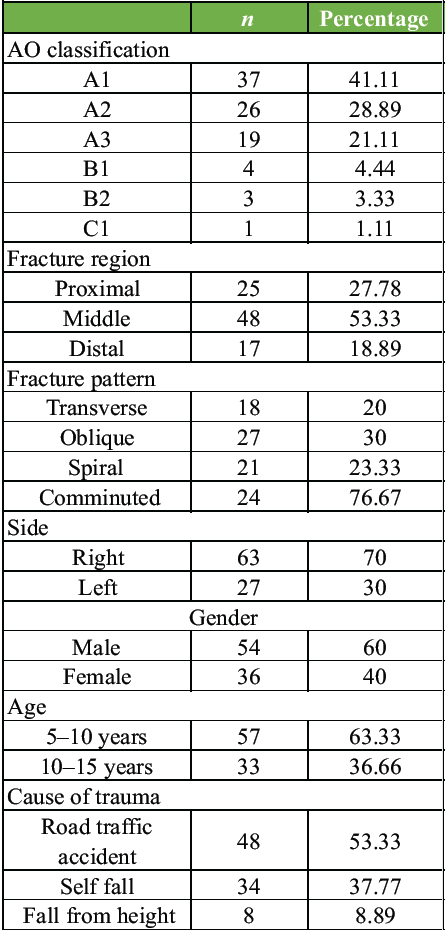

Closed reduction and internal fixation with titanium elastic nailing (TEN) for pediatric femoral fractures gave better results. Ninety pediatric patients who sustained femoral fractures (45 stable and 45 unstable) were treated with titanium nailing over a period of 1.5 years between January 2024 and October 2025. Patient demographics and associated injuries are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of patients

There were 57 cases, 5–10 years of age, and 33 patients, 10–15 years of age. The mode of injury was mainly road traffic accident (48 cases, 53.33%); self-fall (34 cases, 37.77%); fall from height (8 cases, 8.89%). Sex distribution was predominantly male (60%, Male 54 – Female 36). The side affected was predominantly right (70%, right 63 – left 27). The fracture pattern distribution was transverse – 18, oblique – 27, spiral – 21, and comminuted – 24. The level of the fracture was upper third – 25, middle third – 48, lower third -17. The time interval between trauma and surgery was within 48 h (76 cases), and the other 14 cases were operated on after 48 h due to respiratory infections and negligence of parents. The duration of surgery was <1 h for 72 cases and more than 1 h for 18 cases. Duration of hospital stay was 0–7 days in 58 cases (64.44%), 8–10 days in 20 cases (22.22%), 11–14 days in 12 cases (13.33%).

Postoperative complications

Complications were (1) pain at the entry site – 6 cases; (2) superficial infection – 3 cases; (3) angulation <10°–8 cases, and >10° in 3 cases. Angulation was seen in 11 patients. The most common type of angulation was varus angulation. 7 patients had varus angulation. The mean varus angulation was 4.2 ± 5.1°. 4 patients had valgus angulation; (4) limb shortening – 7 cases. LLD was measured by orthoroentgenogram. The length of the fracture side was approximately 0.71 ± 0.58 cm (range 0–2.09 cm) longer than the intact side. There were 2 patients with LLD of 1–2 cm, 4 patients had LLD of <1 cm, and 1 patient had LLD of >2 cm. There was no statistically significant relationship between the type, location, and age of fracture of the LLD (P > 0.05).

The outcome was assessed using Flynn’s criteria based on (1) limb length in equality, (2) malalignment, (3) unresolved pain, and (4) other complications. The outcome was excellent in 63 cases (70%), satisfactory in 23 cases (25.56%), and there were poor results in 4 cases (4.44%).

Radiographs in the coronal and sagittal planes were obtained to assess fracture union and determine the appropriate timing for weight bearing. The mean time to weight bearing for patients was 10.3 weeks (range 8–12 weeks). All fractures achieved complete healing. Fracture union occurred in all cases within 3 months, with an overall average of 11.1 weeks. Specifically, stable fractures united in an average of 10.8 weeks, while unstable fractures took approximately 11.6 weeks to achieve union.

Pediatric femoral fractures are the most common pediatric orthopedic injuries requiring hospital admission and active surgical intervention. Non-operative management remains effective for very young children; its limitations are prolonged immobilization, joint stiffness, and psychological stress. This encouraged surgical stabilization in older children. Earlier, it was treated by conservative means, such as Thomas splint, hip Spica cast, which had associated complications, such as improper perineal toileting, plaster sores, loss of reduction, and angulation [10]. Conservative treatment methods are used as standard in the treatment of children under 5 years [11]. There are different treatment options for femur fractures in children who are between 6 and 15 years old. The choice of surgical treatment in this age group depends on the age of the patient, the localization of the fracture, and the experience of the surgeon. TEN is the most commonly used treatment method in patients who are between 6 and 15 years old. It is based on ESIN principles and offers the best balance between fracture stability and elasticity [6]. In this age group, it is important that the patients move during treatment independently. The return of the child to the social environment is important in terms of psychosocial development. Taking time off work during the course of care will cause financial loss for the family [12]. So nowadays, surgical interventions are more preferred. Among the operative techniques, the flexible intra-medullary nails, such as the titanium elastic nail, are more commonly used [13]. TENS system (TENS) employs a three-point fixation principle, allowing controlled micromotion at the fracture site to promote callus formation. This technique preserves the periosteum and fracture hematoma, ensuring biological healing while maintaining physis integrity. Titanium’s elasticity and compatibility also reduce the risk of stress shielding compared with stainless steel implants. Compared to other fixation techniques, TENS minimizes soft-tissue damage, avoids growth plate injury, and reduces infection rates. Rigid intramedullary nails risk avascular necrosis of the femoral head, while plate osteosynthesis requires extensive exposure. External fixation has issues, such as pin tract infection and delayed union, making TENS preferable for diaphyseal fractures in children. Titanium elastic nails function based on the principle of three-point fixation, achieved through the symmetrical bracing effect of two elastic nails inserted into the metaphysis, each contacting the inner cortex at three points. This configuration provides four key mechanical properties: Flexural stability, axial stability, translational stability, and rotational stability. All four properties are crucial for attaining optimal fracture healing and functional outcomes [14]. TEN is an elastic intramedullary fixation method that functions on the principle of three-point fixation, providing resistance to both distraction and compression forces [6,15]. The ends of the nails are secured at the entry points and within the metaphysis at the opposite end of the bone. The nails are pre-bent beyond their elastic limit, which creates a stable curvature that resists both straightening and further bending, generating tension within the intramedullary canal and minimizing the risk of deformity. Using a third nail in a single bone is generally unnecessary, as it disrupts the balance of the bipolar construct [16]. The TEN gave the best results in transverse and oblique (stable) fracture patterns in terms of fracture union, no angulation, and loss of reduction/collapse, whereas in spiral and comminuted (unstable) fracture patterns, though there were excellent and satisfactory results, there was collapse/loss of reduction, and angulation was seen [17]. Several authors have reported acceptable limits of angulation in pediatric fractures. Cadman and Neer suggested that a maximum angulation of 15° is acceptable, while Buehler et al. reported that angulation of up to 20° in the coronal plane and up to 30° in the sagittal plane can be considered appropriate [18]. Flynn et al. reported that lower than 10° of angulation is an acceptable limit [6]. LLD is a known and unavoidable complication of elastic intramedullary nailing that is performed for pediatric femur shaft fractures. LLD is associated with age, sex, and fracture type. Overgrowth is more common in patients aged 2–10 [19]. In 1921, Truesdell described that the fracture healing process stimulates bone growth in femoral shaft fractures in children [20]. Staheli reported that overgrowth was greatest in the proximal part of the femur [21]. On the contrary, Henry reported that overgrowth was greatest in the distal part of the femur [22]. According to Flynn’s criteria, the most common complication that caused satisfactory and poor results was the angulation. According to Flynn’s criteria, poor results were seen in our study in four patients. Three of these patients had angular deformity, and one patient had LLD >2 cm.

Based on the findings of our study, the TEN system (TENS) is an excellent option for treating pediatric femoral fractures. It provides elastic stability, which promotes rapid fracture healing while allowing early mobilization and resulting in a lower complication rate compared to other treatment methods. TENS is simple, reliable, minimally invasive, and efficient, with shorter operative time, reduced blood loss, minimal radiation exposure, shorter hospital stay, and a reasonable time to bone union. Its advantages, including early weight bearing, rapid healing, and minimal disruption of bone growth, make it a physiological and effective method for managing femoral shaft fractures in children aged 5–15 years. Stable pediatric femoral diaphyseal fractures demonstrate very good outcomes with minimal complications. Unstable fractures generally show favorable results; however, in our study, three cases developed angular deformities, and one case had limb shortening. For severely unstable pediatric femoral diaphyseal fractures, alternative operative techniques may provide better outcomes. TENS is an effective, straightforward, and rapid method for treating pediatric femoral shaft fractures, associated with minimal complications. Adhering to fundamental principles and technical guidelines can further reduce the risk of complications. Although LLD is a relatively common occurrence in childhood femur fractures, it typically does not cause significant functional limitations in daily activities.

“TENS is a safe, effective, and minimally invasive method for treating pediatric femoral shaft fractures in children aged 5–15 years. It provides elastic stability, preserves the physis, promotes rapid fracture healing, allows early mobilization, and is associated with low complication rates. While stable fractures achieve excellent outcomes, severely unstable fractures may require alternative surgical techniques.

References

- 1. Flynn JM, Schwend RM. Management of pediatric femoral shaft fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:347-59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Allen JD, Murr K, Albitar F, Jacobs C, Moghadamian ES, Muchow R. Titanium elastic nailing has superior value to plate fixation of midshaft femur fractures in children 5 to 11 years. J Pediatr Orthop 2018;38:e111-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Naseem M, Moton RZ, Siddiqui MA. Comparison of titanium elastic nails versus Thomas splint traction for treatment of pediatric femur shaft fracture. J Pak Med Assoc 2015;65 11 Suppl 3:S160-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Madhuri V, Dutt V, Gahukamble AD, Tharyan P. Interventions for treating femoral shaft fractures in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;7:CD009076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Singh J, Kaur H. Evaluation of safety and effectiveness of elastic nailing as treatment option for fracture of femur in Children. Sch J Appl Med Sci 2016;4:546-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Flynn JM, Hresko T, Reynolds RA, Blasier RD, Davidson R, Kasser J. Titanium elastic nails for pediatric femur fractures: A multicenter study of early results with analysis of complications. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:4-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Metaizeau JP, Prevot J, Schmitt M. Reduction and fixation of fractures of the neck of the radious be centro-medullary pinning. Original technic. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1980;66:47-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Bhaskar A. Treatment of long bone fractures in children by flexible titanium elastic nails. Indian J Orthop Traumatol 2005;39:166-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Aksoy C, Caolar O, Yazyoy M, Surat A. Pediatric femoral fractures: A comparison of compression-plate fixation and flexible intramedullary nail fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003;85:III263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Levy J, Ward WT. Pediatric femur fractures: An overview of treatment. Orthopedics 1993;16:183-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Buckley SL. Current trends in the treatment of femoral shaft fractures in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997;338:60-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Hedin H, Borgquist L, Larsson S. A cost analysis of three methods of treating femoral shaft fractures in children: A comparison of traction in hospital, traction in hospital/home and external fixation. Acta Orthop Scand 2004;75:241-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Rathjen KE, Riccio AI, De La Garza D. Stainless steel flexible intramedullary fixation of unstable femoral shaft fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2007;27:432-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Sink EL, Gralla J, Repine M. Complications of pediatric femur fractures treated with titanium elastic nails: A comparison of fracture types. J Pediatr Orthop 2005;25:577-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Ligier JN, Metaizeau JP, Prevot J, Lascombes P. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:74-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Sink EL, Hedequist D, Morgan SJ, Hresko T. Results and technique of unstable pediatric femoral fractures treated with submuscular bridge plating. J Pediatr Orthop 2006;26:177-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Narayanan UG, Hyman JE, Wainwright AM, Rang M, Alman BA. Complications of elastic stable intramedullary nail fixation of pediatric femoral fractures, and how to avoid them. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:363-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Buehler KC, Thompson JD, Sponseller PD, Black BE, Buckley SL, Griffin PP. A prospective study of early spica casting outcomes in the treatment of femoral shaft fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;15:30-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Shapiro F. Fractures of the femoral shaft in children. The overgrowth phenomenon. Acta Orthop Scand 1981;52:649-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Truesdell ED. Inequality of the lower extremities following fracture of the shaft of the femur in children. Ann Surg 1921;74:498-500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Staheli LT. Femoral and tibial growth following femoral shaft fracture in childhood. Clin. Orthop Relat Res 1967;55:159-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Henry AN. Overgrowth after femoral fracture shaft fracture in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1963;45:222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]