Reduced bone mineral density, altered body mass index, and suboptimal nutrition are key risk factors for stress fractures in paramilitary recruits, warranting early bone health screening and targeted preventive interventions in high-demand training programs.

Dr. Avinash Kumar Upadhyay, Department of Orthopaedics, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: avinashupadhyay93@gmail.com

Background: Paramilitary recruits undergo repetitive high-intensity physical training, predisposing them to overuse musculoskeletal injuries such as stress fractures. Bone mineral density (BMD) and body mass index (BMI) are key determinants of bone strength, yet limited data exist from Indian paramilitary populations. This study aimed to evaluate BMD status and examine its association with BMI and stress fractures among active recruits.

Materials and Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among 200 paramilitary recruits (mean age 26.3 ± 3.88 years). BMD was measured at the calcaneus using a quantitative ultrasound densitometer (CM-300). BMI was calculated using standard anthropometric techniques. Stress fractures were diagnosed based on clinical evaluation, medical record review, and radiographic confirmation when indicated. Dietary pattern, rank, and lifestyle factors were recorded using a structured questionnaire. Associations were analyzed using chi-square tests and correlation statistics, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results: The mean BMD T-score was –0.676 ± 0.572, with 24.5% of participants demonstrating osteopenia. Stress fractures were documented in 16% of recruits. Abnormal BMI (underweight 2.5%, overweight 13%) showed a significant association with osteopenia (P = 0.029). Low BMD was strongly associated with stress fractures, with 78.1% of fracture cases exhibiting osteopenia (P < 0.01). Assistant commandants had a higher prevalence of low BMD compared with constables (35.5% vs. 17.7%, P = 0.005). Vegetarian recruits demonstrated significantly higher osteopenia and stress-fracture rates (P < 0.01).

Conclusion: Low BMD and abnormal BMI significantly increase susceptibility to stress fractures among paramilitary recruits. The high prevalence of osteopenia despite intensive physical activity highlights the need for routine BMD screening, BMI-focused conditioning, and structured nutritional interventions to enhance bone health and reduce training-related injuries.

Keywords: Bone mineral density, Body mass index, Stress fractures, Paramilitary recruits, Quantitative ultrasound.

Stress fractures represent a significant cause of morbidity in physically active populations, particularly among military and paramilitary recruits exposed to repetitive mechanical loading and high-intensity training. These injuries are multifactorial in origin, arising from the interaction between skeletal strength, anthropometric characteristics, nutritional status, and training-related factors. Bone mineral density (BMD) has long been recognized as a fundamental determinant of bone strength and fracture susceptibility. Cummings and Black first demonstrated that reduced BMD is strongly predictive of fracture risk, establishing BMD as a cornerstone in the assessment of skeletal health [1].

Body mass index (BMI) is another critical factor influencing bone health and stress fracture risk. Previous studies have shown that low BMI is associated with reduced bone mass and a higher incidence of stress fractures in physically active individuals [2,3]. Furthermore, low energy availability has been implicated in impaired bone metabolism and increased susceptibility to skeletal injuries [4]. Training-related injuries in military recruits are influenced by a complex interplay of physical fitness, training load, and anthropometric variables [5]. The interrelationship between energy availability, BMI, and stress fracture risk has been further clarified by Nattiv et al., who highlighted the combined influence of metabolic and mechanical factors on skeletal integrity [6]. Nutritional deficiencies, particularly inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake, have also been reported in military populations and linked to compromised bone health [7].

Subsequent studies in military and paramilitary cohorts have consistently demonstrated that low BMD is a key determinant of stress fracture risk [8,9]. Evidence from paramilitary populations further suggests that training load and skeletal health jointly influence injury patterns [10]. Recent investigations and systematic reviews have reinforced the multifactorial etiology of stress fractures, integrating biomechanical, physiological, and training-related determinants [11,12,13,14,15]. Despite this growing body of evidence, data from Indian paramilitary populations remain limited. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to assess BMD and its correlation with BMI and stress fractures among paramilitary recruits.

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among 200 active paramilitary recruits aged 18–50 years at a training center in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. All participants were medically fit and engaged in regular physical training. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal (IEC No. 89/IEC/2023, approval date: September 10, 2024).

Inclusion criteria

- Active paramilitary recruits

- Medically fit for training

- Provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

- Known metabolic bone disorders

- Chronic systemic illnesses affecting bone metabolism

- Use of medications influencing BMD (corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, etc.).

BMD assessment

BMD was measured at the calcaneus using a Quantitative Ultrasound Bone Densitometer (CM-300) (Fig. 1). T-scores were interpreted as per the World Health

Figure 1: Illustrates the evaluation of bone mineral density at the calcaneus in paramilitary personnel utilizing the CM-300 ultrasound-based bone densitometer.

Organization (WHO) criteria:

- Normal: ≥−1.0

- Osteopenia: −1.0–−2.5

- Osteoporosis: ≤−2.5.

Quantitative ultrasound was selected for its portability, safety, and feasibility for field assessments.

Anthropometric measurements and BMI classification

Height and weight were recorded using standard calibrated instruments. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2) and categorized using the WHO standards as underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.99), and overweight (≥25).

Stress fracture diagnosis

Stress fractures were diagnosed based on clinical examination (localized tenderness, pain on activity), review of medical records, and radiographic evaluation (X-ray or magnetic resonance imaging) when indicated.

Questionnaire and lifestyle data

A structured questionnaire recorded demographic details, rank, duration of service, dietary pattern (vegetarian/non-vegetarian), training exposure, and history of musculoskeletal injury. Dietary data were included due to their known influence on bone health.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using EPI Info 7.0. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequencies) were calculated. The chi-square test assessed associations between categorical variables such as BMI category, diet, rank, and osteopenia. Correlation analysis evaluated the relationship between BMD and BMI. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 200 paramilitary recruits enrolled from the SSB Academy, Bhopal, the majority belonged to the 20–30-year age group (80.5%), with progressively fewer subjects in the 31–40-year (18%) and 41–50-year (1.5%) categories (Table 1).

Table 1: Age distribution among the study subjects

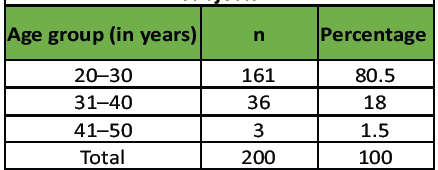

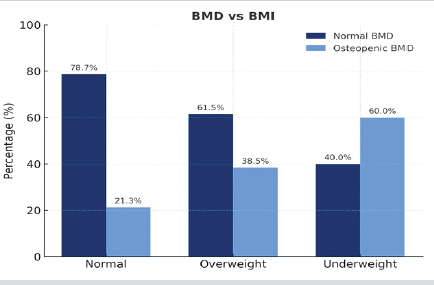

The study cohort was predominantly male, with males accounting for 97% and females for 3% of the population, reflecting the gender composition of paramilitary forces. The mean bone mineral density (BMD) T-score was −0.676 ± 0.572; 75.5% of recruits demonstrated normal BMD, while 24.5% were classified as osteopenic, and none met criteria for osteoporosis. With respect to body mass index (BMI), most participants had a normal BMI (84.5%), whereas 13% were overweight and 2.5% were underweight. Deviations from normal BMI were significantly associated with reduced BMD, with a higher prevalence of osteopenia observed among recruits with abnormal BMI (P = 0.029). (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2: Association between BMD and BMI

Figure 2: Distribution of bone mineral density status across body mass index categories among paramilitary recruits, demonstrating a higher prevalence of osteopenia in recruits with abnormal body mass index.

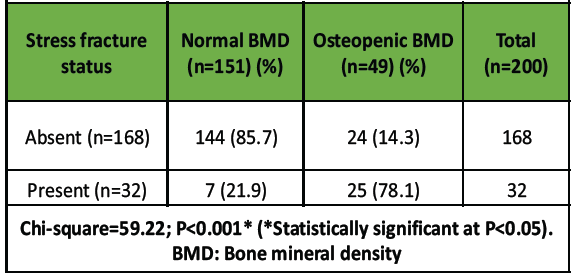

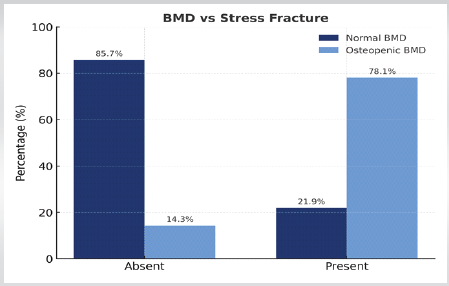

Stress fractures were documented in 16% of the recruits, and most of these fractures involved bones of the lower extremity. A strong relationship was observed between low BMD and stress fractures, as 78.1% of recruits with stress fractures had osteopenia compared with only 14.3% of those without fractures (P < 0.01) (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Table 3: Association between BMD and stress fracture

Figure 3: Comparison of bone mineral density status between recruits with and without stress fractures, showing a significantly higher proportion of osteopenia (78.1%) among those with stress fractures.

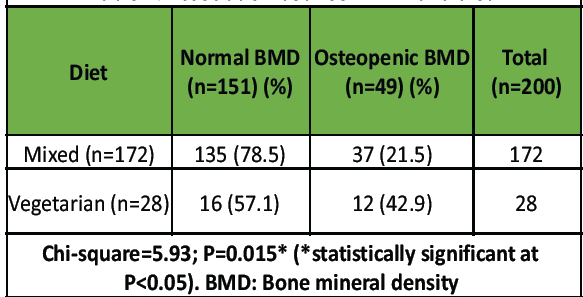

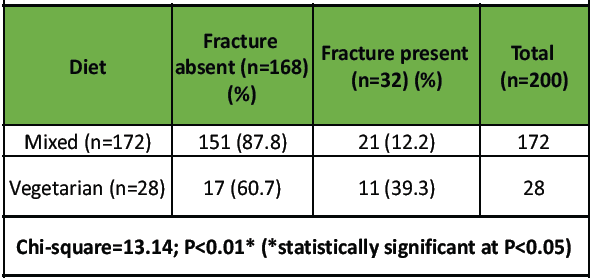

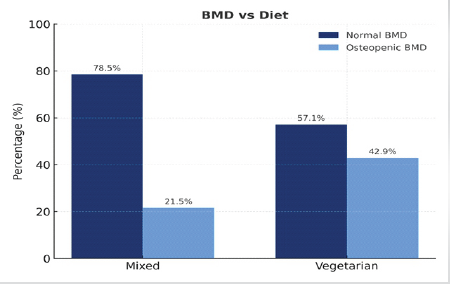

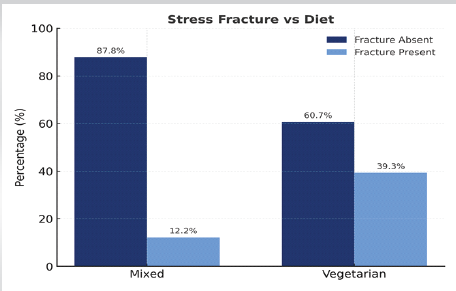

Rank-based analysis showed that osteopenia was significantly more prevalent among assistant commandants (35.5%) compared with constables (17.7%), and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.005). Dietary assessment revealed that vegetarian recruits had a significantly higher prevalence of both osteopenia and stress fractures compared with non-vegetarians (P < 0.01) (Table 4 and 5; Fig. 4 and Fig. 5).

Table 4: Association between BMD and diet

Table 5: Association between stress fracture and diet

Figure 4: Comparison of bone mineral density by dietary pattern showing a significantly higher prevalence of osteopenia among vegetarian recruits (42.9%) compared with those consuming a mixed diet (21.5%) (P < 0.05).

Figure 5: Dietary pattern-wise distribution of stress fractures among paramilitary recruits, showing a significantly higher occurrence of stress fractures among vegetarian recruits (39.3%) compared with those consuming a mixed diet (12.2%) (P < 0.05).

The present study identifies significant associations between BMD, BMI, dietary patterns, and the occurrence of stress fractures among paramilitary recruits undergoing structured basic training at the Sashastra Seema Bal Academy, Bhopal. These findings suggest that skeletal health, anthropometric characteristics, and nutritional factors may contribute to variations in stress fracture susceptibility in physically demanding populations. Importantly, this study provides data from an Indian paramilitary cohort, a group that remains relatively underrepresented in existing literature despite exposure to repetitive mechanical loading and intensive physical training.

In the present cohort, the mean BMI was 22.6 ± 2.06 kg/m2, with most recruits falling within the normal range, while 13% were overweight and 2.5% were underweight. This distribution is comparable to that reported in selected military and physically active populations. A statistically significant association was observed between BMI and BMD (χ2 = 7.08, P = 0.029) (Table 2, Fig. 2), indicating that deviations from normal BMI were associated with altered bone density. These findings are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that extremes of body mass are associated with compromised skeletal health [2,3,6,15]. Although the present study did not employ multivariate or non-linear modeling, the observed pattern suggests that both low and high BMI may be associated with reduced BMD and potentially greater vulnerability to stress-related skeletal injuries.

The prevalence of osteopenia in this study was 24.5%, while stress fractures were identified in 16% of recruits. These figures are broadly comparable to those reported in selected military cohorts, underscoring the clinical relevance of stress fractures in populations exposed to repetitive loading [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. A particularly noteworthy finding was the strong association between BMD and stress fractures (χ2 = 59.22, P < 0.001) (Table 3, Fig. 3) , with 78.1% of recruits with stress fractures exhibiting osteopenic BMD. This association suggests that reduced bone density is closely linked to stress fracture occurrence, consistent with previous observations in both civilian and military populations [1,8,9]. From a biomechanical perspective, reduced BMD may impair bone microarchitecture and remodeling capacity, thereby increasing susceptibility to microdamage accumulation under repetitive mechanical stress.

Dietary factors were also associated with bone health and injury risk. Osteopenia was more prevalent among recruits following a vegetarian diet compared to those consuming a mixed diet (χ2 = 5.93, P = 0.015) (Table 4, Fig. 4), and stress fractures were significantly more frequent in this group (χ2 = 13.14, P < 0.01) (Table 5, Fig. 5). These findings suggest that nutritional adequacy, including protein and micronutrient intake, may influence skeletal health. However, dietary patterns in the present study were not analyzed in terms of caloric intake, protein consumption, vitamin D status, or calcium intake; therefore, the observed associations should be interpreted cautiously and cannot be attributed to diet type alone. Nevertheless, these results highlight nutrition as a potentially modifiable factor in stress fracture prevention.

Differences in bone health were also observed across occupational ranks. Osteopenia was significantly more prevalent among assistant commanders compared to constables (χ2 = 8.06, P = 0.005). The underlying reasons for this difference could not be determined in the present study and may reflect variations in baseline characteristics, training exposure, or lifestyle factors. However, the prevalence of stress fractures did not differ significantly between ranks (P = 0.95), suggesting that bone density may play a more influential role in stress fracture susceptibility than rank-specific occupational exposure alone.

The findings of the present study align with contemporary evidence supporting the multifactorial etiology of stress fractures. Previous research has demonstrated that stress fractures result from the interaction of skeletal health, training load, biomechanical factors, and nutritional status [11,12,13,14,15]. Predictive models in military populations have further emphasized the importance of integrating bone health and anthropometric parameters in risk stratification [12,13]. By extending these observations to an Indian paramilitary cohort, the present study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of stress fracture risk in diverse training environments.

From a clinical perspective, the observed associations underscore the potential value of early identification of recruits at risk of skeletal injuries. BMD assessment may be considered as part of risk stratification strategies in high-demand training populations, while monitoring of BMI and nutritional status may aid in identifying individuals vulnerable to compromised bone health. Collectively, these findings suggest that integrated preventive strategies – encompassing nutritional optimization, individualized training protocols, and periodic evaluation of bone health – may help reduce the burden of stress fractures in paramilitary recruits.

The findings of this study demonstrate that reduced BMD and deviations from normal BMI are significant and independent contributors to stress-fracture susceptibility among paramilitary recruits. The observation that nearly one-fourth of highly active young recruits exhibit osteopenia underscores a critical gap between training demands and physiological adaptation. The strong association of low BMD with stress fractures highlights the need for early screening and targeted preventive strategies, while the influence of BMI and dietary habits, particularly vegetarian diets, emphasizes the importance of individualized nutritional and conditioning interventions. Collectively, these findings point to the necessity of integrating bone health surveillance, evidence-based training modulation, and nutritional optimization into paramilitary training programs to enhance musculoskeletal resilience and reduce injury-related operational downtime.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations. Its cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships between BMD, BMI, and stress fractures. BMD was measured using quantitative ultrasound instead of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, which may reduce measurement precision. Dietary habits, training load, and prior injuries were self-reported, introducing potential recall bias. Imaging

was performed only for clinically suspected cases, so asymptomatic stress fractures might have been missed. The study population consisted almost entirely of male recruits; therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to female personnel. Finally, as the study was conducted at a single training center, generalizability to other paramilitary forces may be limited.

Routine BMD assessment, BMI monitoring, targeted nutritional intervention, and the implementation of tailored physical activity programs for high-risk individuals can significantly reduce stress-fracture risk and enhance operational readiness among paramilitary personnel.

References

- 1. Cummings SR, Black DM. Bone mineral density and the prediction of fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res 1985;5:629-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Reinking MF, Austin TM, Hayes AM. Low body mass index and the development of stress fractures in athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2004;34:465-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Barrack RL, Gibbs AE, DeLuca SA. Effect of body mass index on the risk of stress fractures in athletes. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:1800-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Loucks AB. Low energy availability and bone health in physically active individuals. Curr Sports Med Rep 2007;6:229-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Grier TL, Knapik JJ, Canada S, Canham-Chervak M, Jones BH. Risk factors associated with training-related injury in military recruits. Public Health 2010;124:417-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Nattiv A, Ackerman KE, Warren MP, De Souza MJ, Messina C, Williams NI, et al. Energy availability, body mass index, and stress fracture risk in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:1142-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Hannon M, Zwart SR, Smith SM. Calcium and vitamin D status in military populations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:1338-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hinton PS, Emerson CP, Loucks AB. Bone health in military personnel: risk factors for stress fractures. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(12):2978–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Lappe JM, Cullen DM, Haynatzki GR, Recker RR. Bone health and stress fractures in military personnel: A longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int 2018;29:839-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Brown T, Patel DR, Roy B. Stress fractures in paramilitary recruits: A study of BMD and training load. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:1-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bennell KL, Brukner PD, Malcolm SA. Risk factors for stress fractures in physically active populations: Recent evidence and prevention strategies. J Strength Cond Res 2021;35:2521-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Cosman F, Ruffing J, Zion M, Uhorchak J, Ralston S, Tendy S, et al. Determinants of stress fracture risk in US Military Academy cadets. Osteoporos Int 2021;32:1201-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Moran DS, Israeli E, Evans RK, Yanovich R, Constantini N, Shabshin N, et al. Prediction model for stress fracture in young elite combat recruits. J Bone Miner Res 2021;36:534-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Silva DS, Rocha LP, Nunes JD, Santos LG, Ferreira EF. Risk factors associated with stress fractures in military personnel: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Sharma R, Gupta A, Singh S, Kumar P. Body mass index and physical training-related injuries in military personnel: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMJ Mil Health 2025;171:1–9. doi:10.1136/military-2024-002779 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]