PFN offers stable fixation and early rehabilitation in unstable peritrochanteric fractures, achieving excellent union rates and functional recovery with minimal complications.

Dr. Yogesh Singh Parihar, Department of Orthopaedics, Gajra Raja Medical College, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: yogeshsinghparihar123@gmail.com

Introduction: Unstable peritrochanteric fractures of the femur are among the most challenging injuries in orthopaedic trauma, especially in the elderly with osteoporotic bone. The proximal femoral nail (PFN), a cephalomedullary device, offers potential biomechanical and clinical advantages.

Objectives: To assess (1) the functional outcome of PFN in unstable peritrochanteric femoral fractures using the Harris hip score (HHS); (2) the radiological outcome using the radiographic union score for hip (RUSH); and (3) complications associated with PFN fixation.

Materials and Methods: A prospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedics, Gajra Raja Medical College and J.A. Group of Hospitals, Gwalior (M.P.), from September 2022 to June 2024. A total of 74 patients with unstable peritrochanteric fractures (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für osteosynthesefragen [AO] 31A2.2-A3.3) were operated on using PFN. Functional outcome (HHS) and radiological outcome (RUSH) were evaluated at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v26 with paired t-tests, considering P < 0.05 significant.

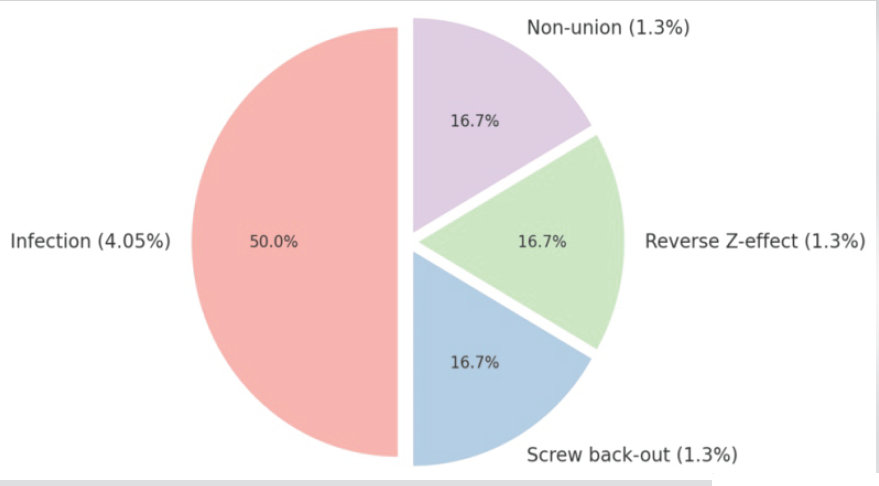

Results: The mean patient age was 54.3 ± 10.7 years; 67.5% were males. The most common fracture pattern was AO 31-A2.2 (40.5%). The mean operative time was 67.5 ± 11.1 min. Mean HHS improved significantly from 57.8 ± 8.9 at 6 weeks to 72.2 ± 4.7 at 3 months and 85.7 ± 6.2 at 6 months (P < 0.001). Radiological union (RUSH >18) was seen in 6.7% at 6 weeks, 54.1% at 3 months, and 98.6% at 6 months. Complications included superficial infection (4.05%), screw back-out (1.3%), reverse Z-effect (1.3%), and non-union (1.3%).

Conclusion: PFN provides stable fixation, early rehabilitation, and high union rates in unstable peritrochanteric fractures. Its minimal soft-tissue dissection and superior biomechanical profile make it a preferred implant, especially in osteoporotic bone.

Keywords: Femur intertrochanteric fracture, Harris hip score, proximal femoral nail, rush, unstable peritrochanteric fracture.

Fractures around the trochanteric region of the femur constitute one of the most frequent injuries encountered in orthopaedic practice. These fractures account for a significant proportion of geriatric trauma, largely resulting from trivial domestic falls in osteoporotic bone, while in younger patients, high-energy trauma such as road traffic accidents (RTAs) and falls from height are common causes [1]. Before the advent of internal fixation, conservative management with traction and prolonged immobilization led to complications like bed sores, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and high mortality [2]. With improved understanding of biomechanics and implant design, early surgical fixation has become the standard of care [3]. Intertrochanteric and peritrochanteric fractures are divided into stable and unstable types based on posteromedial and lateral wall integrity [4]. Unstable fractures exhibit comminution, a thin lateral wall, or a reverse oblique pattern, predisposing to varus collapse, screw cut-out, and implant failure [5]. Extramedullary devices (such as the dynamic hip screw [DHS]) offer good results in stable patterns but have higher failure rates in unstable fractures due to the longer lever arm and higher bending moment [6]. The proximal femoral nail (PFN), introduced in the late 1990s, provides mechanical superiority by reducing the bending moment, allowing controlled impaction, and maintaining alignment [7]. Despite widespread use, outcome variability exists due to patient factors, fracture configuration, surgical expertise, and implant placement. Limited prospective Indian data exist focusing on PFN outcomes in unstable peritrochanteric fractures, particularly from central India. Hence, the present study aimed to: Evaluate functional outcomes using the Harris Hip Score (HHS), assess radiological union using the Radiographic Union Score for Hip (RUSH), and analyze complications and implant-related issues associated with PFN fixation. This prospective Indian study contributes regional data from Central India on functional and radiological outcomes following PFN fixation of unstable peritrochanteric fractures. Unlike prior reports, it incorporates both HHS and RUSH with effect-size analysis, establishing the magnitude of improvement and offering statistically strengthened evidence supporting PFN’s efficacy.

Study design and setting

This was a prospective observational study conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma Centre, Gajra Raja Medical College and J.A. Group of Hospitals, Gwalior (M.P., India), over 22 months (September 2022–June 2024). All patients presenting with unstable peritrochanteric femoral fractures were assessed for eligibility. Before commencement, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC/GRMC/ORTHO/2022/43), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was estimated using the formula for single-proportion studies:

n = (Z2 × P × Q )/d2

where:

n = Required sample size

Z = Standard normal deviate corresponding to 95% confidence level (1.96)

P = Anticipated prevalence or proportion (assumed at 0.05 = 5%)

Q = 1 – P = 0.95

d = absolute precision or allowable error (5% = 0.05)

n = ([1.96]2 × 0.05 × 0.95)/(0.05)2 = 73.98

Thus, the minimum required sample size was 74, which was achieved during the study period. The assumption of 5% prevalence was based on previous institutional data and comparable Indian epidemiological studies on hip fractures [1].

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

Adults aged >18 years with unstable peritrochanteric fractures of the femur, classified as Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO)/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) 31A2.2 to 31A3.3, patients medically fit for surgery and willing to provide informed consent, and patients available for a minimum of 6-month follow-up.

Exclusion criteria

Open, pathological, or infected fractures. Polytrauma cases or fractures associated with neurovascular injury, patients with previous ipsilateral hip surgery, patients unwilling to consent, or patients lost to follow-up.

Pre-operative evaluation and preparation

All patients underwent detailed clinical examination and radiographic evaluation with anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the pelvis and affected hip. Routine hematological investigations, an electrocardiogram, and a chest X-ray were performed for surgical clearance. Fractures were classified according to the AO/OTA 2018 classification system. Pre-operative traction and limb alignment were maintained until surgery.

Surgical technique

All surgeries were performed under spinal anesthesia on a fracture table, with the affected limb placed in traction and adduction to facilitate anatomical reduction under C-arm fluoroscopic guidance. A standard lateral incision centered over the greater trochanter was used for surgical exposure. Closed reduction was attempted in all cases, whereas open reduction was reserved for irreducible fractures. The entry point for nail insertion was made at the tip or slightly medial to the greater trochanter using an awl. A PFN of appropriate diameter (ranging from 9 to 12 mm) and length was inserted over a guidewire, with the neck-shaft angle varying between 125° and 135°, selected according to patient anatomy and fracture pattern. Proximal locking was performed using two screws – a lag screw and a derotation screw – under fluoroscopic control, ensuring that the Tip-Apex Distance (TAD) was maintained below 25 mm to minimize the risk of screw cut-out. Distal locking was carried out either dynamically or statically, depending on the stability of the fracture configuration. Finally, a layered closure was performed after confirming satisfactory reduction, nail placement, and screw positioning under fluoroscopy. Intraoperative parameters such as operative time, blood loss, and any technical complications were recorded.

Post-operative protocol

Day 1: Quadriceps setting, ankle pump exercises, and static hip movements.

Day 2–3: Sitting and non-weight-bearing ambulation using a walker.

2 weeks: Suture removal and radiographic evaluation.

6 weeks: Partial weight-bearing encouraged as tolerated.

12 weeks onward: Full weight bearing permitted after clinical and radiological evidence of union (RUSH ≥18).

Patients were followed up at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months with radiographs taken at each visit to assess healing, implant position, and complications.

Outcome assessment

Functional outcome

Evaluated using the HHS [8], which assesses pain, gait, activities of daily living, deformity, and range of motion, scored from 0 to 100 (Excellent ≥90, Good 80–89, Fair 70–79, and Poor <70).

Radiological outcome

Measured by RUSH. Each cortex (anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral) was assessed for callus and fracture line visibility (score range 10–30). Scores >18 were considered radiologically united [9].

Complications

Both intraoperative (e.g., fracture extension, screw malposition, and technical errors) and post-operative (infection, implant failure, Z-effect, and non-union) complications were documented.

Biomechanical studies have consistently emphasized the mechanical advantages of intramedullary (IM) fixation systems, such as the PFN, over extramedullary devices in the management of unstable peritrochanteric fractures. The IM position allows the implant to act as a load-sharing device, reducing the bending moment and stress on the fixation construct while maintaining a shorter lever arm during axial loading. This translates to greater resistance against varus collapse and rotational displacement, particularly in comminuted or osteoporotic bone. The dual-screw configuration of the PFN provides enhanced rotational control of the femoral head-neck fragment, promoting stable fixation even in complex fracture patterns. Such biomechanical superiority of IM devices compared to DHSs has been validated in controlled in vitro experiments [10], supporting their use as the preferred implant for unstable intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize the demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population, with continuous variables expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of continuous data distributions. For longitudinal comparisons, a paired t-test was used to evaluate changes in mean HHS and RUSH across successive follow-up intervals (6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months). The Chi-square test was utilized to compare categorical variables, such as the rate of fracture union and incidence of complications. To assess relationships between continuous variables, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to determine the association between patient age and final HHS. Confidence intervals (CIs) were computed at the 95% level, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphical representations, including bar charts and line graphs, were created to visually depict the progression of functional and radiological outcomes over time.

Ethical considerations

All participants provided informed written consent before enrollment in the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Gajra Raja Medical College, Gwalior (Ref. No. IEC/GRMC/ORTHO/2022/43). Strict confidentiality of patient data was maintained by anonymizing all identifiers. No external funding was received for this research, and the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Demographic profile

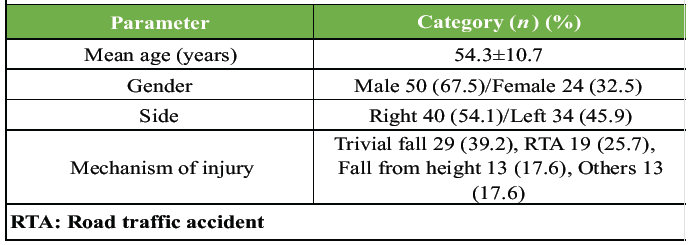

A total of 74 patients were included (Table 1). The mean age was 54.3 ± 10.7 years (range 27–80), with most (28.2%) in the 51–60-year age group, reflecting the prevalence of osteoporotic fragility fractures. There was a male predominance (67.5%), likely due to higher trauma exposure. The right side was involved in 54.1% of cases. Trivial falls (39.2%) were the most common cause, followed by RTAs (25.7%).

Table 1: Demographic distribution of study participants shows the age, gender, and side distribution of patients included in the study (n=74)

Fracture pattern (AO classification)

As found in the study, AO 31-A2.2 fractures were most frequent (40.5%), followed by A3.3 (27.1%), representing highly unstable patterns. These results parallel findings by Schipper et al. [4], who also reported A2.2 as the predominant subtype.

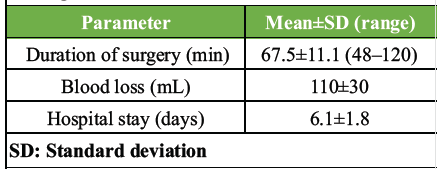

Operative parameters

As shown in Table 2, the mean operative time was 67.5 ± 11.1 min (range 48–120), with average blood loss of 110 ± 30 ml and a mean hospital stay of 6.1 ± 1.8 days. These figures highlight the efficiency of PFN fixation, requiring less operative time and shorter hospitalization compared with extramedullary devices (e.g., DHS, mean 90–100 min) reported in earlier studies by Dousa et al. [6].

Table 2: Operative parameters and intraoperative findings

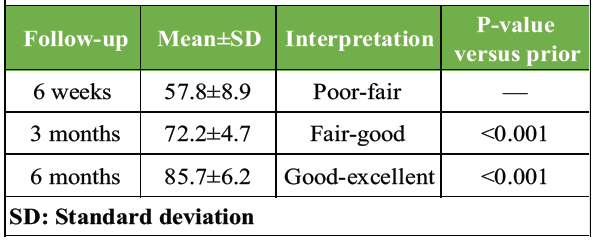

Functional outcomes (HHS)

The functional recovery of patients following PFN was evaluated using the HHS at successive follow-ups (Table 3). The mean HHS improved significantly from 57.8 ± 8.9 at 6 weeks to 72.2 ± 4.7 at 3 months, and further to 85.7 ± 6.2 at 6 months (P < 0.001). The mean difference in HHS between 6 weeks and 6 months was 27.9 points (95% CI: 25.8–30.0), corresponding to a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.41), indicating substantial improvement in pain, walking ability, and daily functional activities over time.

Table 3: Functional outcome assessed by the Harris hip score at 6-week, 3-month, and 6-month follow-ups

At the final follow-up, 59 patients (79.7%) achieved excellent results (HHS ≥90), 12 patients (16.2%) had good results (HHS 80–89), and 3 patients (4.1%) were graded fair (HHS 70–79). None had poor outcomes. Younger patients (<60 years) generally achieved higher HHS scores, whereas older patients tended to have slightly delayed recovery. A moderate negative correlation was observed between age and final HHS (Pearson’s r = −0.41, 95% CI: −0.59– −0.19), suggesting age-related functional decline. Overall, these results highlight that early mobilization, stable fixation, and gradual load-bearing under guided physiotherapy resulted in significant functional improvement by the end of 6 months.

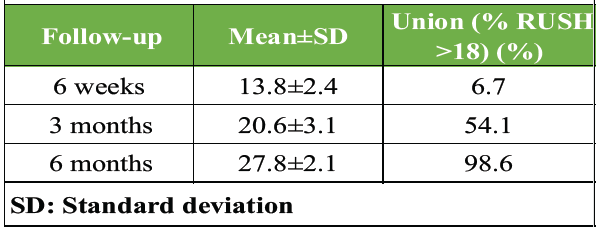

Radiological outcome (RUSH score)

Radiological healing was assessed using the RUSH at each follow-up (Table 4). The mean RUSH score was 13.8 ± 2.1 at 6 weeks, 20.6 ± 3.2 at 3 months, and 27.8 ± 2.4 at 6 months, indicating progressive callus formation and cortical bridging across fracture sites (P < 0.001). The mean improvement in RUSH score from 6 weeks to 6 months was 14.0 points (95% CI: 12.9–15.1), corresponding to a very large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.96), confirming excellent radiological progression and strong evidence of union.

Table 4: Radiological outcome assessed by radiographic union score for hip (RUSH)

At the 6-month follow-up, 73 out of 74 patients (98.6%) achieved complete radiological union (RUSH >18), with only 1 case (1.3%) showing delayed union but eventual consolidation by 9 months. Our findings are consistent with previous Indian studies reporting favorable outcomes of PFN in unstable subtrochanteric and peritrochanteric fractures [11]. The overall union rate (98.6%, 95% CI: 93.2–99.9%) was comparable to previously published literature, including studies by Mandice et al. and Rashid et al. [12,13]. The trend of radiological improvement is a consistent increase in RUSH scores across time points, indicating reliable osteosynthesis stability and biological fracture healing with the PFN construct. The results substantiate that PFN provides superior axial and rotational stability, promoting early union even in comminuted and osteoporotic fractures.

Complications

Various post-operative complications are seen in follow-up (Fig. 1). The overall rate was 8%, with superficial infection (4.05%) being the most common. Other isolated events included one each of screw back-out, reverse Z-effect, and non-union (1.3% each). No implant breakage, deep infection, or intraoperative fracture was encountered. These findings are in agreement with prior studies [12,13] reporting complication rates ranging from 8% to 10%.

Figure 1: Distribution of post-operative complications.

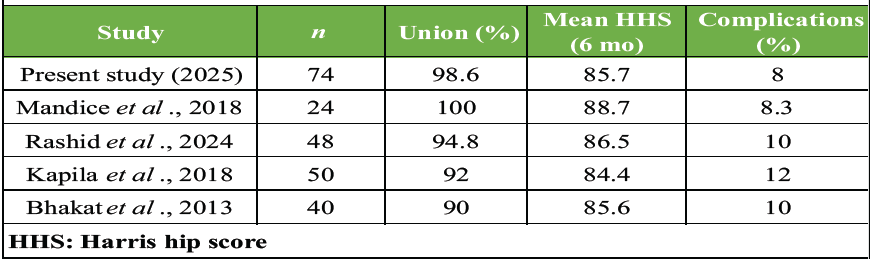

Comparative literature analysis

Table 5 compares this study’s results with major published series. The present study demonstrated one of the highest union rates (98.6%) with an excellent mean functional outcome (HHS 85.7). The current study’s outcomes align with global data, reinforcing PFN as an optimal implant in unstable peritrochanteric fractures.

Table 5: Comparison of functional and union outcomes with previous studies

Unstable peritrochanteric fractures of the femur represent a major therapeutic challenge, particularly in the elderly population with osteoporotic bone. Early surgical stabilization with a load-sharing device is critical to restore mobility, reduce morbidity, and prevent complications associated with prolonged recumbency, such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary infection, and pressure ulcers. The present prospective study evaluates the functional and radiological outcomes of PFN in unstable peritrochanteric fractures and provides additional insight into complication trends and clinical applicability in an Indian tertiary care setting.

Comparison with previous literature

The mean patient age in this study was 54.3 ± 10.7 years, consistent with the demographic pattern reported by Bindulal and Mohammed [11] (mean 54.0 years) and Mandice et al. [12] (mean 55.1 years). The predominance of male patients (67.5%) corresponds to Indian trauma demographics, where males are more exposed to high-energy mechanisms such as RTAs and occupational hazards. Most fractures (39.2%) followed trivial falls, consistent with Dhanwal et al. [1], highlighting osteoporosis as a major underlying factor in low-energy trauma among the elderly. In our study, the mean HHS improved from 57.8 at 6 weeks to 85.7 at 6 months, showing a steady and significant improvement in functional recovery (P < 0.001). These findings are comparable to Mandice et al. (2018), who reported a mean HHS of 88.7, and Rashid et al. (2024), who documented 86.5 at a similar follow-up. The outcomes also align with Bhakat and Bandyopadhayay [14], who observed significantly higher functional scores with PFN compared to DHS fixation (85.6 vs. 77.3, respectively). Radiological assessment using the RUSH in our cohort demonstrated union in 98.6% of patients by 6 months, confirming excellent osteosynthetic stability. These results parallel the 92–100% union rates reported in multiple Indian and international studies, including Kapila et al. [15]. The mean RUSH score of 27.8 at 6 months in our study is indicative of robust healing and maintained alignment throughout follow-up. The complication rate in our series was 8%, comparable to Mandice et al. (2018) (8.3%) and lower than the 10–12% reported by Kapila et al. (2018) and Rashid et al. (2024). Superficial infection (4.05%) was the most common complication, resolving with oral antibiotics and dressing changes. The reverse Z-effect observed in one patient in our series is a well-recognized mechanical complication associated with the PFN design, in which the inferior lag screw migrates medially, and the superior screw backs out laterally. This phenomenon was first described by Strauss et al. [16], who demonstrated in a controlled biomechanical study that differential screw loading, inadequate bone purchase, or suboptimal insertion angles could produce toggling forces leading to opposite screw migrations. Such effects are often related to poor bone quality or failure to maintain an adequate (TAD <25 mm). No cases of intraoperative fracture propagation, implant breakage, or deep infection were observed, emphasizing that proper reduction technique, entry point selection, and (TAD <25 mm) are essential to prevent mechanical failure.

Biomechanical and clinical perspective

From a biomechanical standpoint, the PFN offers distinct advantages over extramedullary devices such as DHS. Its IM location shortens the lever arm, thereby reducing bending moments across the implant-bone interface and allowing for controlled impaction at the fracture site. This provides enhanced resistance to varus collapse, particularly in AO/OTA A2 and A3 patterns where posteromedial or lateral wall comminution compromises stability. The dual-screw design of the PFN provides rotational stability to the femoral head-neck fragment, whereas distal locking confers additional rotational and axial rigidity. The minimally invasive nature of PFN surgery also preserves the fracture hematoma, promoting biological healing. In contrast, DHS requires extensive soft-tissue dissection and is more prone to fixation failure in unstable fracture patterns due to excessive varus and screw cut-out forces. Early mobilization is a key clinical advantage of PFN. In our cohort, patients commenced bedside mobilization by post-operative day 2–3 and partial weight-bearing at 6 weeks, significantly reducing the risk of post-operative complications associated with prolonged immobilization. Early rehabilitation translates directly into improved HHS, shorter hospital stays, and better long-term functional outcomes, as corroborated by Rashid et al. (2024).

Clinical implications

The findings from this study reinforce the clinical utility of PFN as a primary fixation device for unstable peritrochanteric fractures. For surgeons, PFN provides a reproducible, technically reliable method with a predictable learning curve, offering biomechanical stability even in osteoporotic bone. For patients, the benefits include reduced post-operative morbidity, early mobilization, and high rates of union. In institutional or resource-limited settings, PFN allows for shorter operative times, less blood loss, and lower hospital costs compared to plate-based systems. Attention to surgical detail – including proper reduction under C-arm, maintenance of TAD <25 mm, and use of dynamic distal locking where indicated – remains vital to achieving optimal outcomes.

Study limitations

Despite the promising results of this study, certain limitations must be acknowledged for proper interpretation. The study was single-centered and observational in design, which may restrict the external validity and generalizability of the findings to other populations and healthcare settings. However, the use of uniform surgical techniques and post-operative protocols within the same institution ensured methodological consistency and minimized inter-operator bias. The sample size (n = 74), though statistically adequate for outcome analysis, was relatively modest and may have limited the ability to detect less frequent complications or perform meaningful subgroup analyses based on age, fracture subtype, or bone quality. The 6-month follow-up period, whereas sufficient for evaluating radiological union and early functional recovery, was not long enough to assess long-term mechanical or biological complications such as implant fatigue failure, late varus collapse, or avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Variability in post-operative rehabilitation compliance among patients could have influenced functional outcomes, as physiotherapy adherence was not objectively standardized or documented across all participants. Furthermore, the absence of a comparative control group – such as cases managed with DHS or PFN Antirotation (PFNA-II)-restricted direct comparison regarding biomechanical superiority, cost-effectiveness, or complication profile of PFN relative to other fixation methods. Nevertheless, the study adds valuable regional data and effect-size-based evidence supporting PFN as a reliable fixation method for unstable peritrochanteric fractures. Future research should aim to conduct multicentric, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with larger cohorts and extended follow-up durations to validate these findings and establish PFN as the gold-standard fixation technique for this challenging fracture pattern.

Summary of findings

Overall, the present study establishes that PFN offers superior biomechanical stability, early functional recovery, and high union rates with minimal complications in unstable peritrochanteric fractures. These outcomes corroborate existing literature, confirming PFN’s position as the implant of choice for this fracture category, particularly in elderly osteoporotic patients requiring rapid rehabilitation.

The findings of this prospective observational study demonstrate that the PFN is a safe, effective, and biomechanically superior fixation method for the management of unstable peritrochanteric fractures of the femur. In our study population of 74 patients, PFN fixation achieved a high radiological union rate (98.6%) within 6 months and resulted in significant improvement in functional outcomes, as evidenced by the mean HHS progression from 57.8 at 6 weeks to 85.7 at 6 months (P < 0.001). The mean RUSH also improved consistently over time, confirming reliable osteosynthesis and progressive callus formation. The overall complication rate was low (8%), with only minor events such as superficial infection and isolated mechanical issues such as screw back-out and reverse Z-effect, all of which were manageable with conservative measures. From a biomechanical perspective, the PFN provides superior load-sharing and stability by being positioned close to the femoral mechanical axis, thereby reducing the bending moment and risk of varus collapse. The dual-screw design enhances rotational stability of the femoral head-neck fragment, and the minimally invasive surgical technique preserves soft tissues and the fracture hematoma, promoting biological healing. These attributes collectively contribute to early mobilization, faster rehabilitation, and decreased post-operative morbidity, particularly in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone. Clinically, PFN fixation enables early weight bearing and functional independence, leading to reduced hospital stay and improved quality of life. Its shorter operative duration, lesser blood loss, and low rate of implant-related complications make it particularly suitable for high-volume centers and resource-limited healthcare settings. The implant’s design ensures optimal biomechanical performance even in complex fracture configurations such as reverse oblique and comminuted patterns (AO/OTA 31A2 and A3 types), which are prone to failure with extramedullary devices such as the DHS. In light of the present study’s outcomes and corroborative evidence from previous literature, PFN should be considered the implant of first choice for unstable peritrochanteric fractures, especially in patients with poor bone quality. However, optimal results are highly dependent on meticulous surgical technique – including accurate reduction under fluoroscopy, correct entry point, maintenance of (TAD <25 mm), and judicious selection of distal locking mode. While our results reinforce the clinical efficacy of PFN, the study’s limitations – including its modest sample size, single-center design, and relatively short follow-up – underscore the need for further multicentric RCTs with longer follow-up periods. Future studies comparing PFN with other contemporary IM systems, such as PFNA-II and Gamma Nail, may help refine implant selection and optimize patient-specific surgical strategies. In conclusion, PFN provides stable internal fixation, facilitates early rehabilitation, and ensures high rates of anatomical and functional recovery in unstable peritrochanteric fractures. Its mechanical advantages, minimally invasive approach, and reproducible clinical outcomes make it a cornerstone in modern orthopaedic trauma management.

PFN provides stable fixation and allows early rehabilitation in unstable peritrochanteric fractures. Its IM load-sharing design ensures high union rates, minimal soft-tissue disruption, and lower complication rates, making it an optimal choice for elderly and osteoporotic patients.

References

- 1. Dhanwal DK, Dennison EM, Harvey NC, Cooper C. Epidemiology of hip fracture: Worldwide geographic variation. Indian J Orthop 2011;45:15-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Egol KA. Skeletal trauma: Basic science, management, and reconstruction. J Am Med Assoc 2010;303:673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Lindskog DM, Baumgaertner MR. Unstable intertrochanteric hip fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:179-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Schipper IB, Marti RK, Van Der Werken C. Unstable trochanteric femoral fractures: Extramedullary or intramedullary fixation. Review of literature. Injury 2004;35:142-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM, Keggi JM. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:1058-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Dousa P, Bartonicek J, Jehlicka D, Skála-Rosenbaum J. Osteosynthesis of trochanteric fractures using proximal femoral nails. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2002;69:22-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Müller-Daniels H. Evolution of Implants for Trochanteric Fracture Fixation. Practice of Intramedullary Locked Nails. Berlin: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Parker MJ, Maheshwar CB. The use of a hip score in assessing the results of treatment of proximal femoral fractures. Int Orthop 1997;21:262-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Bhandari M, Chiavaras M, Parasu N, Choudur H, Ayeni O, Chakravertty R, et al. Radiographic union score for hip substantially improves agreement between surgeons and radiologists. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Weiser L, Ruppel AA, Nüchtern JV, Sellenschloh K, Zeichen J, Püschel K, et al. Extra- vs. Intramedullary treatment of pertrochanteric fractures: A biomechanical in vitro study comparing dynamic hip screw and intramedullary nail. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015;135:1101-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bindulal VA, Mohammed N. Functional outcome of comminuted unstable subtrochanteric fractures treated by proximal femoral nail [PFN]. Int J Orthop Sci 2017;3:1152-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Mandice CJ, Khan R, Anandan H. Functional outcome of unstable intertrochanteric fractures managed with proximal femoral nail: A prospective analysis. Int J Res Orthop 2018;4:945-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Rashid RH, Zahid M, Mariam F, Ali M, Moiz H, Mohib Y. Effectiveness of proximal femur nail in the management of unstable per-trochanteric fractures: A retrospective cohort study. Cureus 2024;16:e58078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Bhakat U, Bandyopadhayay R. Comparitive study between proximal femoral nailing and dynamic hip screw in intertrochanteric fracture of femur. Open J Orthop 2013;3:291-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kapila R, Singh P, Mahajan S. Functional outcome of proximal femoral nail (P.F.N) in the management of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures femur. J Med Sci Clin Res 2018;6:682-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Strauss EJ, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ, Egol KA. The “Z-effect” phenomenon defined: A laboratory study. J Orthop Res 2007;25:1568-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]