Meticulous pre-operative planning, appropriate anesthetic strategies, optimized positioning, and technical modifications during arthroscopic knee surgery can enable safe procedures and satisfactory functional outcomes in morbidly obese patients.

Dr. A K Sanjay, Department of Arthroscopy and Sports Medicine, Centre for Sports Science, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: drsanjayak@gmail.com

Introduction: Obesity is an increasing global health burden and a significant contributor to knee joint pathology. Arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients poses unique perioperative challenges that may influence surgical safety and functional outcomes.

Aim: The aim of the study was to identify key perioperative challenges encountered during arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients and to describe practical, reproducible technical adaptations that facilitate safe and effective arthroscopy in this high-risk population.

Materials and Methods: A retrospective review was conducted on 50 morbidly obese patients (body mass index [BMI] ≥35 kg/m2) who underwent arthroscopic knee surgery between January 2021 and December 2024. Demographic data, comorbidities, anesthetic and intraoperative adaptations, and functional outcomes using the Tegner-Lysholm score were analyzed.

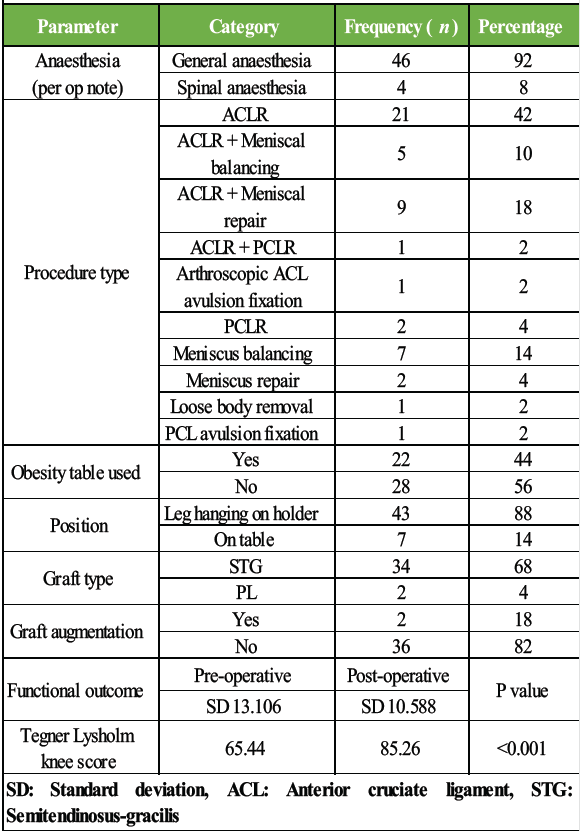

Results: The mean patient age was 33.60 ± 11.30 years, with a mean BMI of 40.23 ± 6.67 kg/m2. Anterior cruciate ligament-related procedures were the most common indication (44%). General anesthesia was used in 92% of cases, and obesity-specific operating tables were required in 44%. At a mean follow-up of 19 months, Tegner-Lysholm scores improved significantly from 65.44 ± 13.10 preoperatively to 85.26 ± 10.59 postoperatively (P < 0.001). Perioperative challenges included anesthetic preparation and airway management, patient positioning, accurate portal and tunnel placement, joint manipulation during meniscal procedures, and post-operative rehabilitation.

Conclusion: Arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients is technically demanding but can provide substantial functional improvement when perioperative challenges are anticipated and addressed through appropriate surgical and anesthetic modifications.

Keywords: Morbid obesity, knee arthroscopy, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, perioperative challenges, functional outcome.

Obesity, a chronic and progressive health condition characterized by excessive body fat, is now recognized as a global epidemic and a major public health concern. According to the World Health Organization, obesity has nearly tripled since 1975, with more than 650 million adults affected worldwide [1]. In India, rising urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, and dietary shifts have accelerated this trend, leading to a growing burden of obesity-related orthopedic issues. The relationship between obesity and knee joint pathology is well-established. Increased mechanical load from excess weight accelerates joint degeneration, particularly of the menisci, articular cartilage, and ligaments, thereby increasing the demand for knee surgeries, including arthroscopy [2]. Arthroscopic knee surgery and rehabilitation are even more important in morbidly obese to mobilize them early and encourage activity to avoid complications due to inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle. Physical activity in obese individuals can be beneficial to a number of critical health markers independent of weight loss or changes in body mass index (BMI) [3]. In morbidly obese patients, arthroscopic knee surgery presents challenges throughout the perioperative period, including anesthetic risks, difficulties in positioning and portal placement, limited visualization, and post-operative rehabilitation concerns. Despite these challenges, early surgical intervention and mobilization are essential to restore function and reduce complications related to prolonged inactivity [4]. This study aims to highlight perioperative challenges encountered during arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients and to share practical strategies that enable safe surgery and satisfactory outcomes.

This is a retrospective study conducted at a high-volume tertiary care center specializing in arthroscopy and sports injuries to evaluate the perioperative challenges and post-operative functional outcomes in morbidly obese patients undergoing arthroscopic knee surgery. It included surgeries performed between January 2021 and December 2024, ensuring a minimum post-operative follow-up of 1 year for all eligible patients. Medical records were analyzed for demographic details, perioperative complications, and follow-up outcomes. Patients aged 18 years and above with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, who underwent arthroscopic knee surgery and had complete records with a minimum follow-up of 1 year, were included. Functional outcomes were assessed using the Lysholm Knee score and Tegner activity scale, both of which are validated and reliable patient-reported outcome measures for assessing functional recovery and early return to sport following arthroscopic knee surgery [5]. Exclusion criteria included patients with BMI <35 kg/m2, incomplete medical records, open or revision procedures, and those with inflammatory or neuromuscular disorders. Purposive sampling was used to include all eligible patients during the study period. Only those fulfilling all inclusion criteria with available surgical and follow-up data were selected. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26 was used for analysis. Institutional ethics approval was obtained, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. A total of 50 patients were included, based on availability during the study period. No comparative or control groups were included. All patients formed a single cohort. Subgroup analysis was done based on comorbidities and procedure types where relevant. As this was a retrospective, single-center observational study, a formal sample size calculation was not performed. The sample size was determined by the total number of consecutive morbidly obese patients who underwent arthroscopic knee surgery during the study period and met the inclusion criteria. Inclusion of all eligible cases was intended to minimize selection bias and to provide a representative description of perioperative challenges encountered in routine clinical practice.

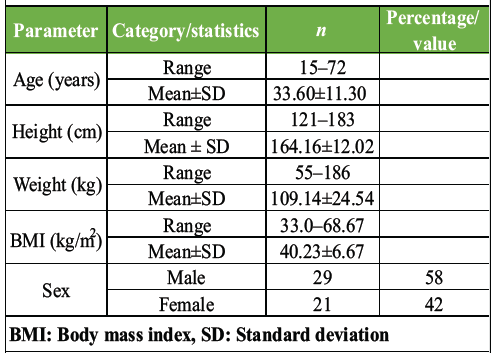

The cohort predominantly consisted of young adults, with a mean age of 33.6 years and a mean BMI of 40.23 kg/m2. Males constituted 58% of the study population (n = 29), while females accounted for 42% (n = 21). About 70% of patients had no significant comorbidities; among those with associated conditions, bronchial asthma, hypothyroidism, and hypertension were the most frequently observed (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of patients (n=50)

Preoperatively, challenges included difficulty in clinical examination due to excessive soft-tissue bulk, suboptimal radiographic imaging, and increased anesthetic evaluation complexity related to morbid obesity and associated comorbidities. Intraoperative challenges included difficult airway management requiring video-assisted intubation, the need for additional equipment and personnel for positioning, and difficulty in accurate portal placement due to excessive soft-tissue, leading to challenges during tunnel placement. No major perioperative or post-operative complications were observed.

Procedure

Pre-operative

There was a predominant use of general anesthesia (92%). Spinal anesthesia was used only in 4 patients (8%). We routinely use GA for all arthroscopic knee surgeries due to its superior muscle relaxation benefits. Pre-operative airway assessment was done using Mallampati grading along with measurement of neck thickness, thyromental distance, restricted mouth opening, limited mandibular protrusion, and a history of difficult airway management. Pre-operative cardiac evaluation with an electrocardiogram and 2D Echo was obtained for all patients to prevent cardiac events.

Intraoperative

.As opposed to a cylindrical tourniquet (Fig. 1a), a conical tourniquet (Fig. 1b) was used in all patients. Krackow maneuver (Fig. 1c) was utilized to achieve a high tourniquet position (Fig. 1d) with adequate padding. Tourniquet length was selected such that the inflatable portion of the cuff completely encircles the limb. Tourniquet was inflated 150 mmHg above systolic blood pressure.

Figure 1: (a) Cylindrical cuff (b) A conical cuff (c) Krackow maneuver (d) high tourniquet with excess soft-tissue retracted distally.

Obesity-specific operating tables (Fig. 2a) were required in nearly half the cases (44%), emphasizing the need for specialized intraoperative equipment when operating on obese patients (Table 2). Standard Operating table was used in 56% of the cases (Fig. 2b)

Figure 2: (a) Obesity table – note how much thicker the base and the rails are (b) Normal table (c) Custom made adjustable leg holder which can be clamped to the table (d) Ramp up position achieved with pillows (e) Leg hanged down by bringing the leg holder down with opposite limb in abduction (f) After final draping.

Table 2: Perioperative technical parameters

Leg-hanging position used in most of our cases (86%), while on table position was used in 7 patients (14%). Leg hanging position was achieved using a custom-made adjustable leg holder (Fig. 2c) with the opposite limb in abduction using a lithotomy post. (Fig. 2d, 2e) Ramp up position was used in all patients to aid in successful intubation during GA. (Fig. 2f) Adequate Preoxygenation was ensured with continuous positive airway pressure of 5–10 cm H2O and 15° head-up position before intubation and 10 cm H2O positive end-expiratory pressure setting after intubation. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (42%) remained the most frequently performed procedure, often combined with medial meniscus repair or balancing. 23 patients underwent meniscal procedures in our series, out of which 12 (52%) underwent balancing (Table 2).

Operative technique

Diagnostic arthroscopy

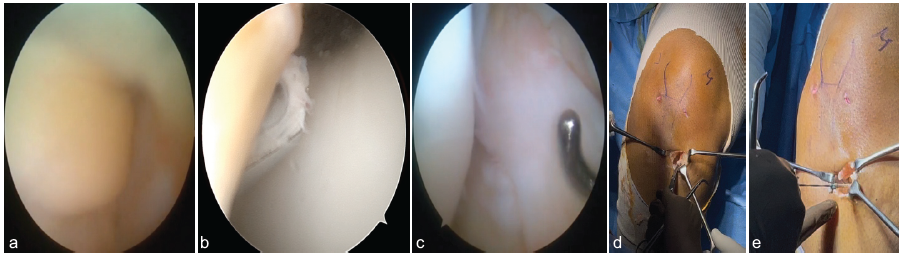

Portal and graft harvest incision were marked before tourniquet inflation after palpation and confirmation of bony landmarks. Diagnostic arthroscopy was performed using standard high anterolateral and anteromedial portals. Anteromedial portal was made under vision with a 16G spinal needle so as to reach the ACL footprint across the roof of intercondylar notch without being too close to the medial femoral condyle. Partial resection of fat pad was performed to gain a good vision of the joint line. In obese patients, excess fat pad was removed by introducing the shaver in suprapatellar pouch and beginning the resection in knee extension and gradually completed while flexing the knee. (Fig. 3a, 3b and 3c) Medial joint line was opened up with the assistant giving valgus and internal rotation, and lateral joint line was opened by lifting the tibia up into a figure of 4 position. When extensive probing or repair work on the posterior horn and root of the medial meniscus was necessary, controlled pie-crusting of the superficial medial collateral ligament was performed approximately 1.5 cm above the medial joint line and 3 cm distal to adductor tubercle along a line joining posterior tibial cortex and adductor tubercle.

Figure 3: (a) Excess Fat pad obstructing view of the notch (b) Resection started from extension with shaver anterior to trochlea (c) Clear view of the notch after completion of resection (d) Sartorius fascia reflected and held with Kocher’s in an open wallet fashion (e) Semitendinosus tendon snared with number 2 ethibond.

Semitendinosus-gracilis graft was used 94% of the patients who underwent ACL reconstruction, and Peroneus longus was used in two patients of which one patient had a concomitant PCL tear requiring reconstruction, and the other patient had a medial side soft-tissue injury.

Graft harvest

Hamstring graft harvest was performed through a liberal oblique incision adjacent to the tibial tuberosity. Pes insertion was identified using the back of a blunt instrument, sartorial fascia was split just above gracilis insertion, and reflected using an inverted L-shaped incision curving toward the tibial tuberosity and held open with a kocher forceps to expose the gracilis and semitendinosus tendons while safeguarding the superficial MCL. (Fig. 3d and 3e). Femoral tunnel was drilled first using the transportal technique. Semitendinosus was tripled, and gracilis was doubled to obtain a 5-strand graft with a minimum diameter of 8.5 mm. Graft augmentation with Mersilene tape was done in two patients, where the graft diameter was <8.5 mm. Femoral side fixation was achieved with a fixed loop endobutton, and tibial side fixation was done with a biocomposite interference screw of the same diameter as the graft.

Post-operative

All patients received a single post-operative dose of low-molecular-weight heparin and were mobilized within 24 h specifically with an adjustable range of motion brace (Fig. 4a and 4b) as opposed to a standard long leg knee brace used routinely in all patients (Fig. 4c and 4d). No anesthetic or thromboembolic complications were observed. Significant improvement in mean Tegner-Lysholm scores from 65.44 ± 13.10 preoperatively to 85.26 ± 10.59 postoperatively (P < 0.001) were observed at 1 year with no major complications (Table 2).

Figure 4: (a and b) adjustable range of motion knee brace. (c and d) standard long leg knee brace.

Pre-operative optimization in obese patients requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach, as these patients – particularly those with associated comorbidities – are at an increased risk of intraoperative complications [6]. Obese patients are particularly vulnerable to perioperative respiratory compromise due to reduced lung volumes, atelectasis, impaired chest wall mechanics, and a higher risk of hypoxemia [7]. Risk factors associated with difficult endotracheal intubation include a Mallampati score of 3/4, a thick neck (>40 cm), limited neck mobility, restricted mouth opening (<3 finger breadths), a short thyromental distance (<6 cm), limited mandibular protrusion, and a documented history of difficult airway management [8]. Cardiac screening is equally important, as obesity is associated with a higher prevalence of arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia, often triggered by hypoxia or underlying cardiac disease [9]. Excess posterior neck fat may lead to excessive cervical flexion and poor glottic visualization during laryngoscopy. A ramped-up position, with the head, neck, and torso elevated until the external auditory meatus aligns with the sternal notch, helps optimize airway alignment, improves glottic exposure, and enhances intubation success in obese patients [10]. Pre-oxygenation strategies are critical since obese patients are at a greater risk of desaturation during apnea. Tourniquet selection is particularly important in obese patients. The cuff should match the limb shape – cylindrical cuffs for cylindrical limbs and conical cuffs for tapered extremities. A wider cuff is preferable, as it achieves arterial occlusion at lower pressures; therefore, the widest cuff that does not interfere with the operative field should be used [11]. A practical method for selecting cuff length is to choose the shortest tourniquet that completely encircles the limb. Excessive overlap can cause instability and shifting, while insufficient overlap may result in uneven pressure and loosening [12]. Krackow first described his maneuver for improved tourniquet position in obese patients, where an assistant pulls soft-tissue distally and maintains traction while securing the cuff. This shifts subcutaneous tissue below the tourniquet, improving cuff support and enabling a more proximal, stable, and effective placement [13]. Previous studies, including Tuncali B et al., suggest obese patients may require higher tourniquet pressures; however, we followed the standard protocol and calculated pressure based on systolic blood pressure, similar to non-obese patients [14].

Arthroscopic access in obese patients is more challenging due to excess adipose tissue, making portal placement less accurate and visualization difficult [15]. Berg described using two operating tables positioned side by side to accommodate larger patients, along with additional portals to complete the diagnostic knee arthroscopy [16]. Modified equipment in the form of an obesity table was often necessary, but standard portals and instruments were sufficient in all cases. Pre-operative marking of bony landmarks and portals improves accuracy and may reduce operative time by avoiding additional portals. Patients who could not be accommodated in the standard table were operated on an obesity table. The obesity table has a higher weight capacity and width; additionally, the reinforced base is positioned more towards the foot end of the table, which allows a leg hanging position even in the obese without the risk of toppling. Leg hanging position is known to provide significantly improved joint distraction in the “hanging leg” and “figure of four” positions compared to keeping the limb on the table [17] although additional assistants may be required to open up the joint during the diagnostic round. In addition, the table allowed greater lowering, facilitating adequate knee flexion required for femoral drilling, which can be challenging due to excess adipose tissue in obese patients. Medial compartment visualization in obese patients can be significantly improved by a partial outside-in release of the superficial medial collateral ligament at the “magic point,” as described by Chernchujit B et al. This technique is routinely employed at our institute and is simple, safe, and easily reproducible [18]. In one case requiring PCL avulsion fixation, a posteromedial portal was created, using a long spinal needle instead of a standard 16G needle, which was too short to traverse the adipose tissue. A liberal oblique incision with broad deep retractors to adequately expose the pes can save operative time in larger patients. Our approach aligns with the OLIBAS hamstring harvest technique by Olivos-Meza A et al., where the open-wallet eversion of the sartorius fascia improves visualization of the individual hamstring tendons [19]. Multiple studies have identified obesity as a significant risk factor for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [20,21]. Low-molecular-weight heparin has been shown to be effective in reducing post-operative thromboembolic events in this patient group [22]. Early ambulation further minimizes the risk of DVT-related complications. In addition, the use of an adjustable knee brace with a controlled range of motion may enhance comfort and support in obese patients, thereby promoting earlier mobilization. Functional outcomes improved significantly, with Tegner-Lysholm scores increasing from 65.44 to 85.26 at 1 year (P < 0.001), indicating successful rehabilitation. Comparable findings have been reported by Harrison et al., demonstrating that obese patients can still achieve meaningful functional recovery post-arthroscopy despite higher complication risks [23]. The study addresses a clinically relevant and under-reported aspect of arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients providing practical insights relevant for practicing surgeons. Since it was conducted at a single tertiary care center with standardized surgical protocols, the study minimizes technical variability and highlights practical, reproducible intraoperative adaptations that can be readily adopted. However, the retrospective design limits control over confounding variables and introduces potential selection bias. Absence of a non-obese control group limits direct comparative assessment. Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights and lays the groundwork for future prospective and comparative research.

Arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients, though technically demanding, can yield excellent functional recovery with appropriate pre-operative preparation and intraoperative adjustments. A multidisciplinary perioperative approach, involving anesthesiologists, nursing staff, and physiotherapists, is crucial for optimal outcomes. Postoperatively, early mobilization with tailored rehabilitation protocols and vigilant monitoring for complications is advised. Future studies should focus on prospective, multicenter, and comparative designs to validate these strategies and assess long-term functional outcomes.

With the rising prevalence of obesity, orthopedic surgeons must be prepared to address the unique challenges of arthroscopic knee surgery in morbidly obese patients. Structured perioperative planning and reproducible technical adaptations are key to achieving optimal outcomes. We recommend performing the procedure in the leg-hanging position under complete general anesthesia to ensure adequate muscle relaxation, facilitate optimal graft harvest, and achieve effective joint distraction. Maintaining a clear surgical field requires meticulous tourniquet control, which can be achieved by using an appropriately sized conical tourniquet, applied with the Krackow maneuver to prevent slippage. Accurate portal placement is best ensured by carefully palpating and marking relevant bony landmarks before tourniquet inflation. Finally, the importance of a high-capacity operating table and the availability of additional surgical assistants cannot be overemphasized in managing these technically demanding procedures.

References

- 1. Verma M, Das M, Sharma P, Kapoor N, Kalra S. Epidemiology of overweight and obesity in Indian adults – a secondary data analysis of the National Family Health Surveys. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2021;15:102166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Tilinca M, Pop TS, Bățagă T, Zazgyva A, Niculescu M. Obesity and knee arthroscopy – a review. J Interdiscip Med 2016;1 Suppl 2:13-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Gaesser GA, Angadi SS. Obesity treatment: Weight loss versus increasing fitness and physical activity for reducing health risks. iScience 2021;24:102995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Pojednic R, D’Arpino E, Halliday I, Bantham A. The benefits of physical activity for people with obesity, independent of weight loss: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:4981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kocher MS, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Sterett WI, Hawkins RJ. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm knee scale for various chondral disorders of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1139-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Glance LG, Wissler R, Mukamel DB, Li Y, Diachun CA, Salloum R, et al. Perioperative outcomes among patients with the modified metabolic syndrome who are undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2010;113:859-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Al-Mulhim AS, Al-Hussaini HA, Al-Jalal BA, Al-Moagal RO, Al-Najjar SA. Obesity disease and surgery. Int J Chronic Dis 2014;2014:652341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Jackson JS, Rondeau B. Mallampati score. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk585119 [Last accessed on 2025 Nov 22]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Seyni-Boureima R, Zhang Z, Antoine MM, Antoine-Frank CD. A review on the anesthetic management of obese patients undergoing surgery. BMC Anesthesiol 2022;22:98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Brodsky JB, LemmensHJ, Brock-Utne JG, Saidman LJ, Levitan R. Anesthetic considerations for bariatric surgery: Proper positioning is important for laryngoscopy. Anesth Analg 2003;96:1841-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Younger AS, McEwen JA, Inkpen K. Wide contoured thigh cuffs and automated limb occlusion measurement allow lower tourniquet pressures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;428:286-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Tourniquet Cuff Selection. Available from: https://tourniquets.org/tourniquet-cuff-selection [Last accessed on 2025 Nov 27]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Krackow KA. A maneuver for improved positioning of a tourniquet in the obese patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;168:80-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Tuncali B, Boya H, Kayhan Z, Araç S. Obese patients require higher, but not high pneumatic tourniquet inflation pressures using a novel technique during total knee arthroplasty. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi 2018;29:40-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Martinez A, Hechtman KS. Arthroscopic technique for the knee in morbidly obese patients. Arthroscopy 2002;18:E13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Berg EE. Knee joint arthroscopy in the morbidly obese. Arthroscopy 1998;14:321-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Kawaguchi Y, Kondo E, Kitamura N, Sakamoto T, Tanaka Y, Yasuda K. Paper # 186: Comparisons of three leg positions for the anatomic double bundle ACL reconstruction using the transtibial technique. Arthroscopy 2011;27:e193-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Chernchujit B, Gajbhiye K, Wanaprasert N, Artha A. Percutaneous partial outside-in release of medial collateral ligament for arthroscopic medial meniscus surgery with tight medial compartment by finding a “magic point”. Arthrosc Tech 2020;9:e935-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Olivos-Meza A, Suarez-Ahedo C, Jiménez-Aroche CA, Olivos-Gárces NA, González-Hernández A, Ibarra C. Anatomic considerations in hamstring tendon harvesting for ligament reconstruction. Arthrosc Tech 2020;9:e191-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Delis KT, Hunt N, Strachan RK, Nicolaides AN. Incidence, natural history and risk factors of deep vein thrombosis in elective knee arthroscopy. Thromb Haemost 2001;86:817-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Holst AG, Jensen G, Prescott E. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism: Results from the Copenhagen city heart study. Circulation 2010;121:1896-903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Wirth T, Schneider B, Misselwitz F, Lomb M, Tüylü H, Egbring RE, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism after knee arthroscopy with low-molecular weight heparin (Reviparin): Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2001;17:393-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Harrison MM, Morrell J, Hopman WM. Influence of obesity on outcome after knee arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 2004;20:691-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]