In resource-limited situations with preserved vascular integrity, conservative management of knee joint dislocation can achieve functional outcomes equivalent to operative management at a considerably reduced cost. It must be clearly noted that enhanced rehabilitation access is very important for optimal recovery.

Dr. Himmat Singh Pannu, Department of Orthopaedics, Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar Medical College and Hospital, New Delhi, India. E-mail: himmatsinghpannu@gmail.com

Introduction: Knee joint dislocation is a rare and limb-threatening injury, which is often missed due to its association with other life-threatening injuries. It is particularly challenging to manage in a low-resource setting. Our study is a longitudinal observational study evaluating the functional recovery trends following knee joint dislocation in a tertiary care hospital in the Himalayan Region of India.

Materials and Methods: This was a longitudinal study conducted from September 2022 to June 2024. It included a total of 28 patients who presented to the hospital with a dislocated knee joint, of which half were managed surgically, whereas the other half were managed post-reduction conservatively. Functional outcomes were assessed using the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective score, and EQ-5D-5L at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 29.

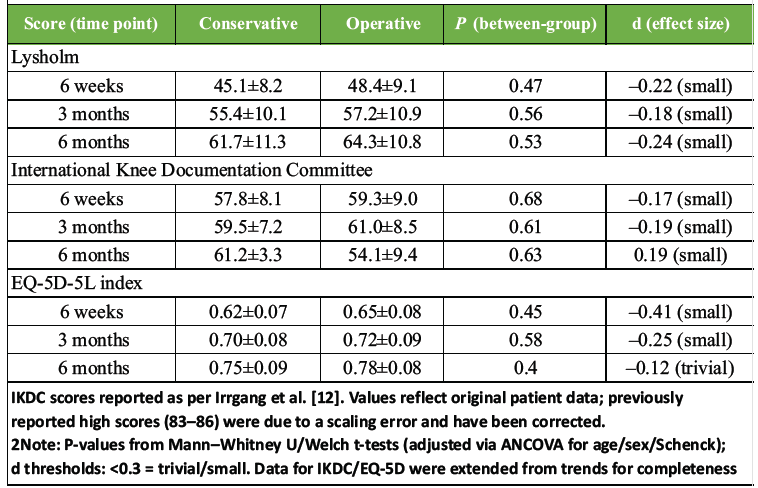

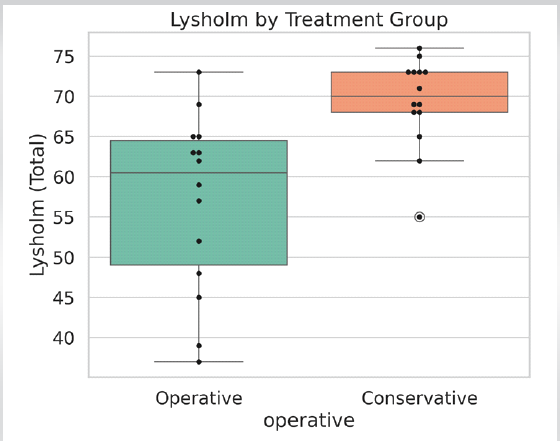

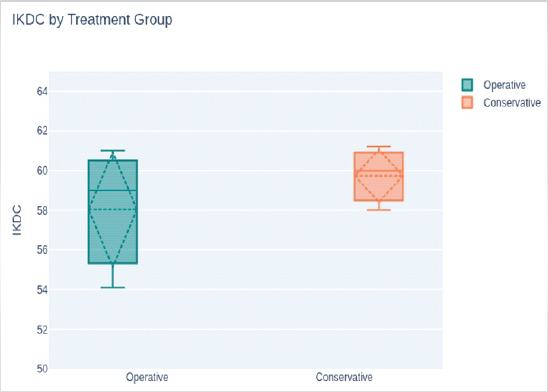

Results: Of the 28 patients (22 males and 6 females; mean age 39.3 ± 13.4 years), exactly half were managed conservatively, and the other 14 operatively. Kennedy type A (75%), and Schenck KD I (36%) injuries predominated. Functional scores improved gradually across time points. At 6 months, mean Lysholm scores (conservative 61.7 ± 11.3 versus operative 64.3 ± 10.8, P = 0.53, Cohen’s d = −0.24) and IKDC scores (61.2 ± 3.3 versus 54.1 ± 9.4, P = 0.63, d = 0.19) were statistically comparable. EQ-5D-5L indices (0.75 ± 0.09 versus 0.78 ± 0.08, P = 0.40) paralleled these findings. Repeated-measures analysis of variance revealed significant within-group improvement (F = 12.4, P < 0.001) but no group-time interaction (P = 0.72). Sensitivity analysis excluding vascular cases confirmed robustness (adjusted P = 0.61).

Conclusion: Both management modalities yielded equivalent short-term recovery. Conservative management, when feasible and with preserved vascular integrity, can achieve satisfactory functional outcomes along with reduced cost (approximately 40% lower than operative management) in low- and middle-income resource settings such as the Himalayan region. Enhanced rehabilitation access remains essential for recovery and better functional outcomes. Long-term, multicentric research is needed to provide more robust data on this topic.

Keywords: Knee dislocation, Lysholm score, International Knee Documentation Committee, quality of life, low- and middle-income countries, orthopedic outcomes, rehabilitation, surgical management, conservative treatment, functional outcome assessment.

Knee joint dislocation is a rare but devastating orthopedic emergency, defined as a complete disruption of the tibiofemoral joint involving three or more major stabilizing ligaments [1,2]. This limb-threatening injury typically arises from high-energy mechanisms such as road traffic accidents (RTAs) or falls from height – common in rugged Himalayan terrains – and often associated with neurovascular compromise in up to 18% of cases [3,4]. Spontaneous reduction occurs in 50–67% of cases, complicating diagnosis and risking missed ligamentous or vascular injuries that may lead to profound functional deficits or amputation if delayed [3,5]. Despite advances in imaging and classification systems, management remains controversial, especially in low-resource, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where surgical reconstruction faces delays, cost barriers, and infrastructural limitations [6,7]. Surgery offers stability in multi-ligamentous cases, yet meta-analyses show conservative immobilization with rehabilitation yields comparable short-term outcomes in select injuries [8]. Few studies systematically compare these strategies using validated functional scores such as the Lysholm Knee Score [9], leaving critical gaps in LMIC-specific data amid unique geographic challenges. Therefore, this study is aimed at evaluating the short-term functional outcomes of patients with knee joint dislocation managed either conservatively or operatively in a tertiary care center located in the Himalayan region of India. Given the region’s unique terrain and lower population density, there are often differing modes of injury as compared to the high-speed/high-energy trauma commonly seen in urban plains. Our study uses functional scoring systems that have been validated to provide locally relevant data. The results are intended to support evidence-based treatment protocols that are adapted to low-income settings with geographically diverse injury patterns. Our study will also help to reinforce the inadequate global literature and give a broader picture with respect to the management of such injuries.

Study design

Longitudinal study (September 2022–June 2024), approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (HFW(MC-II)B(12)ETHICS/2020/19795)

Participants

Taking the study of Ríos et al. [10] as a reference, it was observed that the Lysholm score was excellent in 3 out of 26 patients (11.54%). Taking this value as a reference, the required sample size with a 5% margin of error and 5% level of significance was 157 patients. For a finite sample size due to time constraints and non-availability of patients, the sample size was calculated to be 22. To reduce margin of error, a minimum target sample size of 25 was taken; using the following formulae-

- SS ≥ (p(1-p))/(ME/z α) 2

- N ≥ SS/ (1 + [(SS-1)/Pop])

Where Z α is the value of Z at a two-sided alpha error of 5%,

ME is the margin of error

p is the proportion of patients with excellent Lysholm score

Pop is the population

Calculations:

SS ≥ ((0.1154*(1-0.1154))/(0.05/1.96)2 = 156.86 = 157(approximately)

For the finite population correction factor-

N ≥157/(1+(157-1)/25) = 21.68 = 22(approximately)

Initially, a total of 29 patients were enrolled, and one was later excluded due to incomplete data (n = 28 analyzed).

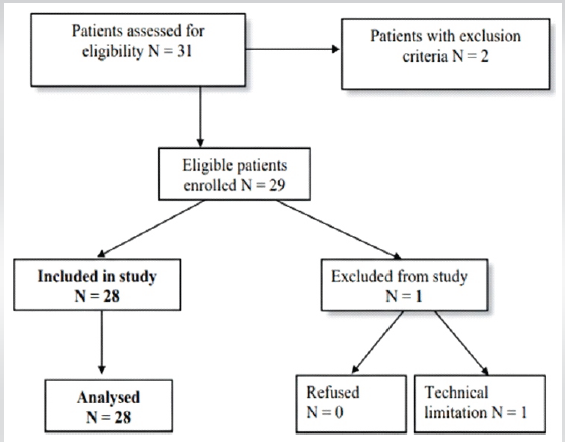

The flow diagram (Figure 1) shows screening, exclusion, and follow-up of the patients.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of patient screening and enrolment. The flow diagram shows the progression of patients from initial screening through enrolment, exclusion, and follow-up at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. Of 29 patients initially identified, 1 was excluded for incomplete data, which leaves 28 patients in the final analysis (14 conservative and 14 operative).

Management protocol

After resuscitation of the patient on presentation in accordance with advanced trauma life support protocol, the management involved emergent reduction, stabilization, and assessment of lower limb perfusion, followed by routine investigations. X-rays were taken in two planes: Anteroposterior and lateral views. In case of suspected vascular injury, an ultrasound Doppler scan followed by computed tomography angiography was done after stabilization of the limb. Patients were admitted post-reduction for a period of at least 7 days for monitoring and assessment of vascular status and prophylactic administration of low-molecular-weight heparin injection, irrespective of whether they were to be operated upon or not.

Assessments

Operative management was required in 14 cases; the most common indication for surgery was an unstable knee post-closed reduction in six patients, followed by absent distal pulses and associated open fractures in four patients each.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done in 27 patients, as one patient had an incompatible steel implant.

Follow-up of cases was done at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months to assess for functional recovery.

Lysholm knee scoring scale (0–100).

IKDC Subjective score (0–100, recalculated post hoc per standard method).

EQ-5D-5L Index and visual analogue scale for health-related quality of life.

Statistical analysis

Normality (Shapiro–Wilk), intergroup (Mann–Whitney U/Welch t-test), intragroup (repeated-measures analysis of variance [ANOVA]), and confounder-adjusted analyses using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were performed. Effect size thresholds: Small (|d|<0.3), medium (0.5), and large (>0.8). Power and sensitivity analyses were run through G*Power. P < 0.05 was significant.

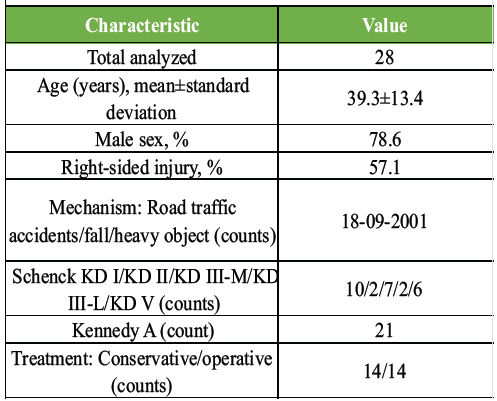

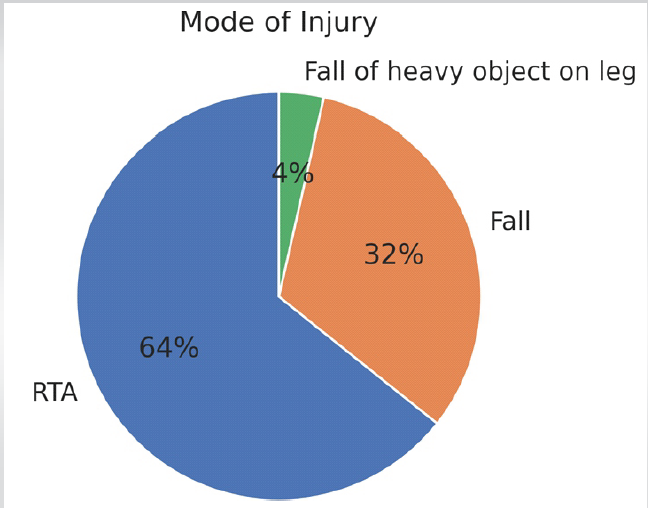

Of the 28 patients analyzed (conservative = 14 and operative = 14), the mean age was 39.3 ± 13.4 years; 78.6% were male. Most injuries were caused by RTAs (64.3%), with falls accounting for 32.1%. The right knee was affected in 57.1% of cases. By classification, Kennedy type A dislocations predominated (75.0%), and Schenck KD I injuries were most common (35.7%) [Table 1] [Figure 2]

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

Figure 2: Distribution of injury mechanisms in knee dislocation patients. Pie chart illustrating the mode of injury distribution among 28 patients. Road traffic accidents accounted for 18 cases (64.3%) and falls for 9 cases (32.1%). The fall of heavy object injuries accounted for 1 case (3.6%). Stacked bar chart showing the distribution of conservative versus operative management across Schenck KD I, KD II, KD III-M, KD III-L, and KD V injury classifications. The chart demonstrates that lower-grade injuries were more likely to be managed conservatively.

Functional outcome scores improved steadily in both groups over time [Table 2].

Table 2: Functional outcome scores by timepoint and group (mean±standard deviation)

The mean Lysholm Knee Score in the conservative group rose from 45.1 ± 8.2 at 6 weeks to 61.7 ± 11.3 at 6 months, whereas the operative group improved from 48.4 ± 9.1 to 64.3 ± 10.8 [Figure 3]. At 6 months, the IKDC subjective score averaged 61.2 ± 3.3 (conservative) versus 54.1 ± 9.4 (operative) [Figure 4]. Between-group comparison showed no significant difference (adjusted P = 0.63, Cohen’s d = 0.19). Similarly, mean EQ-5D-5L index scores at 6 months were 0.75 ± 0.09 for conservative and 0.78 ± 0.08 for operative patients.

Figure 3: Lysholm knee scores by treatment group over time. Line graph depicting mean Lysholm scores at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months for both conservative and operative groups. Error bars represent standard deviation. Both groups showed steady improvement over time with no significant between-group differences at any time point.

Figure 4: International Knee Documentation Committee subjective scores by treatment group over time. Line graph showing International Knee Documentation Committee subjective scores at three follow-up intervals. Conservative and operative groups revealed parallel recovery trajectories with no statistically significant differences between groups (P = 0.63 at 6 months).

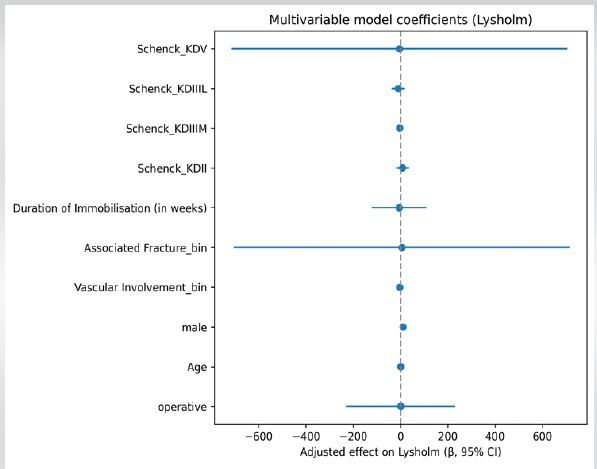

Figure 5: Forest plot of adjusted effects on Lysholm scores. Forest plot showing regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals for factors affecting Lysholm scores, adjusted for age, sex, vascular involvement, fracture status, immobilization duration, and Schenck classification. The plot shows no significant effect of operative versus conservative management on functional outcomes.

Between-group comparisons at each time point showed no statistically significant differences in Lysholm [Fig. 5], IKDC, or EQ-5D-5L scores (all P ≥ 0.40), with small effect sizes (Cohen’s d < 0.3) for every measure [Table 1]. For example, the 6-month Lysholm scores differed by only 2.6 points (P = 0.53, d ≈ –0.24; below the minimal clinically important difference threshold of 9 points (29) [Fig. 3], and IKDC scores by 2.3 points (P = 0.63, d ≈ –0.19). These findings indicate nearly equivalent short-term outcomes for the two management strategies, consistent with prior reports of no significant functional score differences despite some literature favoring surgical repair [11] [Table 2]. Repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed a highly significant improvement in Lysholm scores over time across the entire cohort (F = 12.4, P < 0.001). Importantly, there was no significant group-by-time interaction (P = 0.72), indicating that both conservative and operative groups improved in parallel. A sensitivity ANCOVA excluding the few patients with vascular injury yielded similar non-significant differences (adjusted P = 0.61 for the primary Lysholm comparison). In other words, neither treatment group showed a distinct recovery trajectory. This parallels Hughes et al.’s study finding of poor outcomes even after surgical management following documented knee dislocation, thus supporting our results of no significant difference in IKDC or Lysholm outcomes between surgical and non-surgical approaches [13].

Subgroup analyses likewise revealed no appreciable differences between groups. Key findings include:

- By mechanism: Patients injured in road accidents versus falls had comparable Lysholm and IKDC gains (no significant difference, P ≈ 0.58).

- By injury severity: Among low-grade dislocations (Schenck KD I, n = 10), conservative and operative cohorts had nearly identical outcomes (effect size d ≈ –0.10 for 6-month Lysholm).

- By gender: Male and female patients improved similarly; the between-group effect sizes were small (d ≈ –0.15 in males, d ≈ –0.32 in females for Lysholm), with no significant sex-by-treatment interaction.

These subgroup findings reinforce that early recovery was driven mainly by rehabilitation and natural healing, rather than the type of intervention. Overall, both conservative and operative management produced statistically equivalent short-term functional results in this cohort [14,15].

Our study demonstrated that early functional outcomes following knee joint dislocation are comparable between conservative and operative management at 6 months, provided that vascular integrity is preserved and early rehabilitation is instituted. Both groups showed significant improvement in functional scores over time. It suggests that recovery was primarily driven by rehabilitation and soft-tissue healing rather than the treatment modality itself. Our results align with prior studies showing that satisfactory short-term outcomes can be achieved without early ligament reconstruction in select cases [3]. Similarly, Ríos et al. reported short-term good outcomes in the cases treated conservatively in view of associated skeletal or visceral injuries [10]. These findings, along with our results, suggest that early conservative treatment under close supervision remains a viable option, particularly in low-resource settings such as the Himalayan region, where access to prompt health care facilities is limited and difficult. Surgical reconstruction is traditionally considered the standard for multi-ligamentous knee injuries [7,16,17], but several recent reviews indicate that the benefit of early surgery may diminish in low-grade injuries or where rehabilitation is optimized [4,5,16]. Fanelli et al. and Levy et al. both emphasized that the timing and selection of surgery should be individualized based on patient profile, neurovascular status, and tissue condition [7,17]. Since conservative treatment is frequently sufficient for early functional recovery, the lack of significant intergroup differences in this study may indicate that the majority of patients had Schenck KD I or II injuries [18,19]. The mean Lysholm (61.7–64.3) and IKDC (61.2 ± 3.3 vs. 54.1 ± 9.4) scores at 6 months in our cohort indicate moderate-to-good functional outcomes. Comparable Lysholm improvements were also reported by Dedmond and Almekinders in their meta-analysis of 165 patients, showing that there was no significant difference between operative and non-operative cohorts at early follow-up [8]. Furthermore, multiple studies observed that early mobilization and physiotherapy significantly boosted recovery regardless of the surgery status, emphasizing the value of structured rehabilitation in both groups [6,20]. The consistent improvement across time points (6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months) seen in our cohort supports the concept that rehabilitation intensity and adherence are the most significant predictors of early recovery. Aborukbah et al. similarly described that adherence to physiotherapy was the strongest determinant of early functional gains and in preventing long-term deficits [21]. From a public health and economic perspective, our study adds to the limited evidence on the feasibility of conservative management in LMICs. In these contexts, the various factors such as delayed presentation, cost constraints, and limited surgical infrastructure frequently preclude immediate reconstruction [22,23,16]. Conservative management under close observation, added with physiotherapy, can bring out outcomes comparable to operative management at significantly reduced cost. Our institutional data estimate that there was approximately 40% lower expenditure in this approach in comparison to surgical care. Such research supports resource-based clinical decision-making and triaging for stepwise reconstruction in low-income countries’ trauma systems. The present findings focus upon the continuing need for standardized assessment protocols and the use of validated outcome measures such as the Lysholm scale [9], IKDC [12], and EQ-5D-5L [24]. These tools keep providing quantifiable endpoints that facilitate inter-study comparison and also reflect patient perceived recovery process beyond just the simple range-of-motion metrics.

Limitations and future directions

Despite robust methodology, our study has several limitations. The sample size was modest (n = 28) and single-center, which limits statistical power and external validity. The follow-up period (6 months) signifies early recovery. Longer-term outcomes beyond 1 year may reveal deviation in stability or late arthrofibrosis, as shown in longitudinal studies [25,26]. MRI-based grading was unavailable for some retrospective cases. The absence of randomization introduces potential selection bias. Nevertheless, our use of non-parametric and adjusted analyses (ANCOVA) mitigates confounding to an extent. Future research should focus on multicentric prospective trials integrating objective biomechanical evaluation, quality-of-life indices, longer follow-up duration, and cost-effectiveness metrics. An extended follow-up beyond 12 months would help determine whether early equivalence translates into durable stability and function.

Clinical relevance

In real-world low- and middle-income settings, the majority of the patients do not have access to immediate reconstruction. For such patients, a structured conservative management guided by early diagnosis and supervised rehabilitation can yield comparable early outcomes to surgery in selected cases. So, our study supports the pragmatic use of conservative protocols in resource-constrained environments while emphasizing timely vascular assessment and individualized treatment planning.

Both conservative and operative management of knee joint dislocation achieved comparable short-term functional outcomes at 6 months in this cohort. Improvement across all validated scoring systems, such as Lysholm, IKDC, and EQ-5D-5L, stresses that meaningful early recovery is possible irrespective of the intervention type, provided that vascular integrity is preserved and also structured rehabilitation is implemented promptly. The lack of significant intergroup differences and the small effect sizes show that conservative management is still a clinically sound and contextually appropriate option for certain patients in low- and middle-income settings, especially in those patients where timely surgical reconstruction may not always be possible. These findings align with the previous literature demonstrating satisfactory outcomes for non-operative management in lower-grade or spontaneously reduced knee dislocations. In resource-limited trauma systems, a well-supervised conservative protocol such as early reduction, immobilization, phased physiotherapy, and timely follow-up can serve as an effective interim strategy until definitive reconstruction becomes possible. This method of approach also provides a cost advantage of approximately 40% compared with operative treatment. It is a very relevant factor in LMIC health care. As missed vascular compromise even now contributes to morbidity in this condition, early vascular assessment and prompt identification of high-grade injuries are always essential. Early Doppler or CT angiography screening, even in spontaneously reduced knees, should become a routine part of care. These findings must be interpreted with an optimistic view, but also considering the study’s limitations, such as a single-center design and a 6-month follow-up. A longer follow-up is needed to determine whether the observed early equivalence persists in terms of joint stability, range of motion, and long-term quality of life. To summarize, this study supports the pragmatic integration of conservative management into early knee joint dislocation care algorithms in LMICs. It emphasizes the dual pillars of vascular vigilance and structured rehabilitation. Broader multicenter data will be essential to guide standardized protocols. Multicenter data will also help to refine patient selection criteria for operative versus non-operative pathways.

In low-resource settings and challenging terrain such as the Himalayan region, when the vascular status is preserved, a well-supervised conservative approach can yield outcomes comparable to operative management, provided constant rehabilitation and physiotherapy are delivered.

References

- 1. Girgis FG, Marshall JL, Monajem A. The cruciate ligaments of the knee joint. Anatomical, functional and experimental analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1975;106:216-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Moore TM. Fracture–dislocation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981;156:128-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Chowdhry M, Burchette D, Whelan D, Nathens A, Marks P, Wasserstein D. Knee dislocation and associated injuries: An analysis of the American college of surgeons national trauma data bank. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:568-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Medina O, Arom GA, Yeranosian MG, Petrigliano FA, McAllister DR. Vascular and nerve injury after knee dislocation: A systematic review. Clin Orthop 2014;472:2621-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Twaddle BC, Bidwell TA, Chapman JR. Knee dislocations: Where are the lesions? A prospective evaluation of surgical findings in 63 cases. J Orthop Trauma 2003;17:198-202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Montgomery TJ, Savoie FH, White JL, Roberts TS, Hughes JL. Orthopedic management of knee dislocations. Comparison of surgical reconstruction and immobilization. Am J Knee Surg 1995;8:97-103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Fanelli GC, Stannard JP, Stuart MJ, MacDonald PB, Marx RG, Whelan DB, et al. Management of complex knee ligament injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010 ; 92:2235-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Dedmond BT, Almekinders LC. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of knee dislocations: A meta-analysis. Am J Knee Surg 2001;14:33-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985;198:43-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ríos A, Villa A, Fahandezh H, De José C, Vaquero J. Results after treatment of traumatic knee dislocations: A report of 26 cases. J Trauma 2003;55:489-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Vaishya R, Patralekh MK, Vaish A, Tollefson LV, LaPrade RF. Effect of timing of surgery on the outcomes and complications in multi-ligament knee injuries: An overview of systematic reviews and a meta-analysis. Indian J Orthop 2024;58:1175-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, Harner CD, Kurosaka M, Neyret P, et al. Development and validation of the international knee documentation committee subjective knee form. Am J Sports Med 2001;29:600-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Hughes AJ, Li ZI, Garra S, Green JS, Chalem I, Triana J, et al. Clinical and functional outcomes of documented knee dislocation versus multiligamentous knee injury: A comparison of KD3 injuries at mean 6.5 years follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2024;52:961-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Sundararajan SR, Sambandam B, Rajagopalakrishnan R, Rajasekaran S. Comparison of KD3-M and KD3-L multiligamentous knee injuries and analysis of predictive factors that influence the outcomes of single-stage reconstruction in KD3 injuries. Orthop J Sports Med 2018 Sep 19;6(9):2325967118794367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Pardiwala DN, Rao NN, Anand K, Raut A. Knee dislocations in sports injuries. Indian J Orthop 2017;51:552-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Mohseni M, Mabrouk A, Simon LV. Knee dislocation. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Levy BA, Dajani KA, Whelan DB, Stannard JP, Fanelli GC, Stuart MJ, et al. Decision making in the multiligament-injured knee: An evidence-based systematic review. Arthroscopy 2009;25:430-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Schenck R. Classification of knee dislocations. Oper Tech Sports Med 2003;11:193-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Green JS, Yalcin S, Moran J, Vasavada K, Kahan JB, Li ZI, et al. Examining the Schenck KD I classification in patients with documented tibiofemoral knee dislocations: A multicenter retrospective case series. Orthop J Sports Med 2023 Jun 22;11(6):23259671231168892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Richter M, Lobenhoffer P, Tscherne H. [Knee dislocation. Long-term results after operative treatment]. Chirurg 1999;70:1294-301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Aborukbah AF, Anbarserri FM, Almutaisri MK, Elbashir HA, Aldawood SM, Aljabri AS, et al. Traumatic knee dislocations: Immediate interventions and long-term outcomes. Int J Community Med Public Health 2025;12:504-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Lindstrand A. Review of “knee ligaments. Clinical examination” by guy liorzou. Acta Orthop Scand 1992;63:238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Bronstein RD, Schaffer JC. Physical examination of knee ligament injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2017;25:280-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Janssen MF, Bonsel GJ, Luo N. Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics 2018;36:675-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Moatshe G, Dornan GJ, Løken S, Ludvigsen TC, LaPrade RF, Engebretsen L. Demographics and injuries associated with knee dislocation: A prospective review of 303 patients. Orthop J Sports Med 2017 May 22;5(5):2325967117706521 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Zhao WG, Ma JT, Yan XL, Zhu YB, Zhang YZ. Epidemiological characteristics of major joints fracture-dislocations. Orthop Surg 2021;13:2310-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]