Early minimally invasive double-row knotless repair provides strong fixation and enables reliable functional recovery in acute proximal hamstring avulsion injuries.

Dr. Hatem B Afana, Department of Orthopaedics, King’s College Hospital, London, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. E-mail: hatembafana@gmail.com

Introduction: Hamstring muscle injuries are among the most common muscle injuries. With about 12% involve avulsion of the proximal origin from the ischial tuberosity.

Case Series: We present the outcome of four patients with acute, complete proximal hamstring tendon avulsions treated with a minimally invasive open repair using a double-row knotless suture anchor construct. The surgical technique, post-operative rehabilitation protocol, and clinical outcomes at 4–6-month follow-up are described. All patients achieved complete functional recovery and returned to their pre-injury activity levels without complications or tendon re-rupture.

Conclusion: These results demonstrate the clinical effectiveness of timely surgical repair using a knotless double-row technique for proximal hamstring avulsions.

Keywords: Proximal hamstring injury, minimal invasive, early surgery, double-row knotless suture anchor.

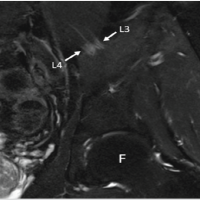

The proximal hamstring complex comprises the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and long head of the biceps femoris muscles, all originating from the ischial tuberosity. These muscles play a vital role in hip extension and knee flexion, making it particularly prone to injury during eccentric muscle contractions, such as those occurring with sudden hip flexion and knee extension during sprinting or jumping [1]. Hamstring injuries are among the most common muscle injuries, accounting for approximately 29% of all injuries in athletes [2]. Although most hamstring injuries occur at the myotendinous junction, about 12% involve avulsion of the proximal origin from the ischial tuberosity [1]. These injuries often cause acute, sharp pain with associated ecchymosis, posterior thigh tenderness, and a characteristic avoidance of knee extension. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the gold standard for confirming diagnosis and grading severity [1]. Several classification systems have been developed to categorize hamstring injuries. Peetron et al. initially proposed an ultrasound-based classification, which et al. later modified using MRI. This system grades injuries based on structural disruption, with grade 1 indicating edema without tissue damage, grade 2 reflecting partial tears, and grade 3 representing complete rupture. Another classification system introduced by et al. emphasizes the anatomical site of the injury, such as intramuscular, myofascial, or myotendinous. The British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification offers additional granularity by combining MRI findings with anatomical site. However, none of these systems reliably predict the time to return to sport or long-term functional recovery [3]. Several risk factors increase the likelihood of proximal hamstring injuries, including advanced age, a history of previous hamstring injuries, and inadequate warm-up routines [4]. Treatment decisions depend on the severity of the injury. While low-grade injuries can be managed conservatively with rest, ice, and protected weight-bearing, complete avulsions, particularly in active individuals or athletes, often require surgical repair to restore strength and function. Both open and endoscopic surgical techniques have shown favorable outcomes, with many patients reporting pain relief and functional recovery [5]. However, surgery is not without risks, including re-rupture, infection, and nerve injury. Research suggests that surgical repair within 5 weeks of injury is associated with improved patient satisfaction and a higher likelihood of returning to pre-injury activity levels [6,7]. Endoscopic repairs are reported to offer better pain relief and range of motion compared to open techniques [8,9]. However, we chose an open, minimally invasive approach for this case presentation, as acute injuries are often accompanied by large hematomas, which can hinder visualization during endoscopic procedures. In our case presentation, we report the outcomes of four patients with acute proximal hamstring avulsions, all treated using a double-row repair with four knotless anchors. The surgical technique was adapted from the approach described by Moatshe et al. [10]. We also describe the rehabilitation protocol followed postoperatively, with a focus on functional outcomes and return to activity.

Inclusion criteria were skeletally mature patients with acute (≤6 weeks) grade III proximal hamstring tendon avulsions confirmed by MRI. Four patients (two men and two women) aged 35–54 years (mean: 43.5 years) presented to our outpatient clinic with acute grade III proximal hamstring avulsion injuries confirmed on MRI. Three injuries resulted from low-energy falls, while one was sports-related. The interval from injury to surgery averaged 10.2 days. All patients were physically active with no major comorbidities apart from one smoker and one asthmatic patient on corticosteroids. Treatment options were discussed in detail, including non-operative and surgical approaches, and all patients chose surgical repair. All underwent surgical repair performed by the senior author (TN), and the same post-operative rehabilitation protocol was followed.

Case 1

A 53-year-old physically active male sustained an acute right-sided proximal hamstring avulsion during recreational exercise. MRI demonstrated complete avulsion of all three hamstring tendons with marked distal retraction. The patient underwent open debridement and surgical reconstruction. Postoperatively, immobilization was achieved with a knee brace locked in full extension for 6 weeks, combined with touch weightbearing and avoidance of active knee flexion. Post-operative physiotherapy followed a standard protocol, including passive range of motion exercises for 6 weeks, followed by active range of motion exercises. At 1-week follow-up, the wound was clean and healing appropriately with satisfactory pain control. At 6 months, the patient demonstrated good functional recovery with mild residual stiffness, slightly reduced range of motion, and improving peri-incisional numbness.

Case 2

A 35-year-old female presented with a left-sided proximal hamstring avulsion following a low-energy fall while walking. MRI confirmed complete avulsion of the proximal hamstring tendons with a diastasis of approximately 3–5 cm. She underwent surgical reconstruction of the proximal hamstrings. Postoperatively, a knee brace locked in extension was used with hip flexion restricted to 45° and touch weight-bearing for 4 weeks. At 1-week follow-up, the wound was well healed, and physiotherapy was initiated. At the final follow-up 14 months postoperatively, she was pain-free but continued to demonstrate limitations in strength and range of motion and further targeted physiotherapy resulted in satisfactory functional outcome.

Case 3

A 41-year-old female sustained a right-sided proximal hamstring avulsion following a fall during normal ambulation. MRI revealed complete tendon avulsion with significant retraction and a large associated fluid collection. She underwent open debridement and reconstruction of the proximal hamstring tendon. Postoperatively, management included a knee brace locked in extension for 6 weeks, limitation of hip flexion to 45°, and touch weightbearing. Early follow-up demonstrated satisfactory wound healing and preserved tendon continuity. At 5 months postoperatively, she showed improved gait and range of motion with residual posterior thigh pain, stiffness, mild peri-scar numbness, and hamstring strength graded at 4/5.

Case 4

A 41-year-old male presented with a right-sided proximal hamstring avulsion after a fall. MRI confirmed complete avulsion of the proximal hamstring tendons. He underwent surgical reconstruction of the proximal hamstrings. Postoperatively, he was treated with a knee brace locked in extension for 6 weeks, hip flexion limited to 45°, and touch weightbearing. Early follow-up showed uncomplicated wound healing and intact neurovascular status. At approximately 4 months postoperatively, the patient reported good functional recovery in activities of daily living with intermittent posterior thigh pain.

Surgical technique

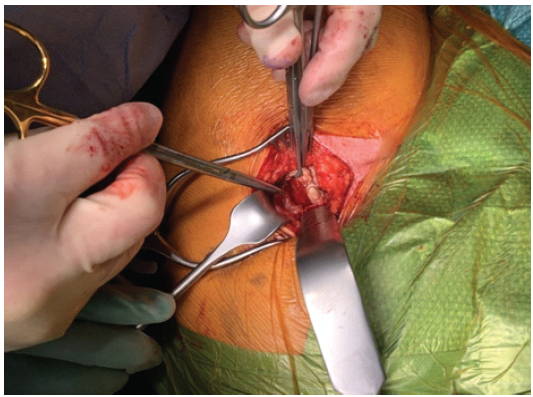

Our surgical approach is based on the method described by Moatshe et al. [10], with minor modifications. Patients were positioned prone under general anesthesia to provide optimal access to the posterior thigh and gluteal region. A 5–8 cm transverse incision along the gluteal crease provided access to the ischial tuberosity and minimal cosmetic impact. After identifying the inferior border of the gluteus maximus muscle, the inferior gluteal fascia was incised to allow for proximal mobilization of the muscle. The ischial tuberosity and overlying fascia were then identified, and the fascia was opened. In acute injuries, any large hematoma and associated fluid were evacuated at this point. The avulsed hamstring tendon stumps were then identified, mobilized proximally, and provisionally secured with two strong sutures (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The torn proximal hamstring tendons are presented after mobilization. The scissors are pointed pointing toward the ischial tuberosity where the anchors will be placed.

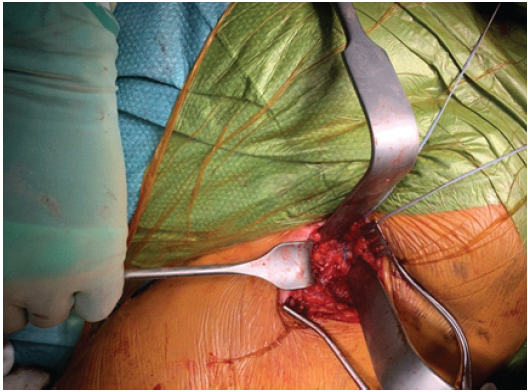

Next, the sciatic nerve, which runs parallel to the hamstrings lateral to the ischial tuberosity, was identified and carefully protected (without traction). If needed, a nerve stimulator confirmed its location in cases of distorted anatomy. Neurolysis was not necessary in these acute cases. Deep blunt retractors were placed inferiorly, medially, and laterally to fully expose the ischium. The hamstring footprint on the ischial tuberosity was prepared by debriding soft tissue and freshening the bone surface with a curette, facilitating tendon-to-bone healing. Care was taken to ensure anchor placement at the native tendon insertion site on the lateral aspect of the ischium. Following Moatshe et al. [10], we performed a double-row repair using four 4.75 mm knotless suture anchors. First, two distal anchors were placed, and their suture tapes were passed through the tendon stumps. The repair was then completed by tensioning these tapes and securing them with the two proximal anchors in pre-drilled tunnels (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Repaired proximal hamstring tendons in the double row repair technique using knotless anchors.

We aimed for at least 1.5 cm spacing between anchors, adjusting for patient anatomy to achieve an anatomic footprint. Care was taken to avoid over-tensioning by confirming full knee extension intraoperatively. If tendon quality had been poor or tension excessive, we would have considered augmenting with an allograft (not needed in this case presentation). After confirming that the sciatic nerve was free of traction, the wound was irrigated and closed in layers, and a knee brace locked in full extension was applied.

Postoperative rehabilitation

Patients used a brace locked in extension for 4 weeks, with hip flexion restricted to 45° in the first 2 weeks. Toe-touch weight bearing was permitted initially, progressing to full weight bearing by 6 weeks. Passive range of motion began after 2 weeks, followed by progressive strengthening. By 4 months, patients were allowed to return to sport-specific training, with full return anticipated by 4–6 months.

All four patients had uneventful recoveries, with no complications or re-ruptures. One patient did experience a fall at 2.5 weeks postoperatively; however, follow-up MRI confirmed that the repair remained intact. At final follow-up (4–6 months post-surgery), all patients had full restoration of function and returned to their pre-injury activity levels.

When evaluating a patient with acute posterior thigh pain following trauma, the differential diagnosis for a proximal hamstring rupture must encompass a broad spectrum of musculoskeletal and neurological etiologies. This will include Grade I–III hamstring strains, chronic tendinopathy, and ischial apophyseal avulsions in young adult patients. Neurological and referred pain sources, such as lumbar radiculopathy, piriformis syndrome, and ischiofemoral impingement, must be excluded, alongside rare but critical conditions like posterior compartment syndrome or deep vein thrombosis. Accurate clinical and imaging differentiation is essential, as complete avulsions often require early surgical repair to restore function. This case presentation includes four patients with acute Grade III proximal hamstring avulsion injuries, each treated using a minimally invasive double-row repair technique. While proximal hamstring avulsions are often associated with high-energy sports injuries [2], three of our cases resulted from low-energy falls, with only one occurring during athletic activity. These findings align with prior studies suggesting that proximal hamstring avulsions can also occur from low-energy mechanisms such as slipping or tripping [11]. A systematic review of operative versus non-operative management found that surgical repair of proximal hamstring avulsions provides significant benefits, including higher patient satisfaction, restored muscle strength, and earlier return to physical activity [12]. In contrast, non-operative treatment of complete avulsions has been linked to persistent strength deficits and lower functional outcomes, underscoring the value of surgery, especially for active individuals. These findings reinforce the role of surgical repair for complete hamstring tendon avulsions. The timing of surgical intervention is critical. Early repair (preferably within 5 weeks of injury) is associated with better functional outcomes, higher patient satisfaction, and a greater likelihood of returning to pre-injury activity [6,7]. In ourpresentation, surgery was performed on average 10.2 days after injury, consistent with recommended practice for optimal recovery. Endoscopic proximal hamstring repairs have gained popularity for potential benefits, including reduced post-operative pain and improved range of motion [8,9]. However, in acute avulsion injuries with large hematomas, an open approach may be more practical, as it provides better visualization and allows evacuation of the hematoma. For our presentation, we used a minimally invasive open technique for these acute cases, though endoscopic repair might offer advantages in chronic injuries with extensive scarring. Biomechanical studies support using multiple smaller anchors for tendon repair. Repairs with several small anchors provide more even load distribution and greater strength than repairs with fewer larger anchors [13]. Similarly, knotless anchor constructs have demonstrated superior cyclic-loading performance and fewer suture-tendon interface failures [14]. Accordingly, we used a double-row repair with four 4.75 mm knotless anchors, which provides a balance between mechanical stability and technical simplicity. Post-operative management is crucial for recovery. A recent systematic review of bracing protocols after hamstring repair found that patients using a knee brace in extension had lower complication and reoperation rates, better outcomes, and higher satisfaction [15]. Accordingly, we applied a knee brace locked in full extension for 4 weeks, limiting hip flexion to 45° during the first 2 weeks. Patients were then allowed to gradually increase activity, with return to sport expected around 4 months after surgery. Our findings demonstrate excellent short-term outcomes for acute proximal hamstring avulsion repairs using a minimally invasive double-row knotless anchor technique. This approach provides reliable fixation and facilitates early rehabilitation. Compared with non-operative management, surgical repair consistently yields better functional outcomes and patient satisfaction. Our results align with this evidence and support early surgical repair within 2–3 weeks of injury as a key determinant of success.

A minimally invasive open double-row knotless repair technique for acute proximal hamstring avulsions provided excellent outcomes in four patients. All achieved full functional recovery without complications. This technique offers a safe, effective, and reproducible method for treating these injuries. Larger comparative studies are needed to confirm long-term benefits and further evaluate open versus endoscopic techniques.

Timely surgical repair of acute proximal hamstring avulsions using a minimally invasive double-row knotless anchor technique offers a safe, effective, and reproducible method that restores strength and function while minimizing complications, making it a valuable option for active patients seeking full return to activity.

References

- 1. Koulouris G, Connell D. Evaluation of the hamstring muscle complex following acute injury. Skeletal Radiol 2003;32:582-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Ahmad CS, Redler LH, Ciccotti MG, Maffulli N, Longo UG, Bradley J. Evaluation and management of hamstring injuries. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:2933-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Wangensteen A, Guermazi A, Tol JL, Roemer FW, Hamilton B, Alonso JM, et al. New MRI muscle classification systems and associations with return to sport after acute hamstring injuries: A prospective study. Eur Radiol 2018;28:3532-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Opar DA, Williams MD, Shield AJ. Hamstring strain injuries: Factors influencing recurrence. Sports Med 2012;42:209-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Yetter TR, Halvorson RT, Wong SE, Harris JD, Allahabadi S. Management of proximal hamstring injuries: Non-operative and operative treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2024;17:373-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Bodendorfer BM, Curley AJ, Kotler JA, Ryan JM, Jejurikar NS, Kumar A, et al. Outcomes after operative and nonoperative treatment of proximal hamstring avulsions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2018;46:2798-808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Best R, Meister A, Meier M, Huth J, Becker U. Predictive factors influencing functional results after proximal hamstring tendon avulsion surgery: A patient-reported outcome study after 227 operations from a single center. Orthop J Sports Med 2021;9:23259671211043097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Kurowicki J, Nawabi T. Endoscopic hamstring repair techniques. Arthroscopy 2021;37:76-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Fletcher AN, Pereira GF, Lau BC, Mather RC 3rd. Endoscopic proximal hamstring repair is safe and efficacious with high patient satisfaction at a minimum of 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 2021;37:3275-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Moatshe G, Chahla J, Vap AR, Ferrari M, Sanchez G, Mitchell JJ, et al. Repair of proximal hamstring tears: A surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech 2017;6:e311-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Looney AM, Day HK, Comfort SM, Donaldson ST, Cohen SB. Proximal hamstring ruptures: Treatment, rehabilitation, and return to play. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2023;16:103-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Rudisill SS, Kucharik MP, Varady NH, Martin SD. Evidence-based management and factors associated with return to play after acute hamstring injury in athletes: A systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med 2021;9:23259671211053833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Hamming MG, Philippon MJ, Rasmussen MT, Ferro FP, Turnbull TL, Trindade CA, et al. Structural properties of the intact proximal hamstring origin and evaluation of varying avulsion repair techniques: An in vitro biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:721-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Gerhardt MB, Assenmacher BS, Chahla J. Proximal hamstring repair: A biomechanical analysis of variable suture anchor constructs. Orthop J Sports Med 2019;7:2325967118824149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Wyatt PB, Ho TD, Hopper HM, Satalich JR, O’Neill CN, Cyrus J, et al. Systematic review of bracing after proximal hamstring repair. Orthop J Sports Med 2024;12:23259671241230045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]