Finger cellulitis, paronychias, and felons are managed by a diverse group of providers in a variety of healthcare settings where notable regional, insurance, and treatment differences exist.

Dr. Bryan G Beutel, Kansas City University, 1750 Independence Avenue, SEP 438, Kansas City, Missouri, 64106, United States. E-mail: bryanbeutel@gmail.com

Introduction: Finger cellulitis, felon, and paronychia may be treated nonoperatively if diagnosed in a timely manner. Delayed or improper treatment may result in progression to more serious conditions, which necessitate intervention by a hand surgeon. This investigation sought to evaluate national demographics and treatment patterns in finger infections.

Materials and Methods: The PearlDiver Mariner database, an insurance claims database with 151 million unique patients within the United States, was used to identify patients with finger cellulitis, felon, and paronychia from 2010 to 2015. Billing events were organized by insurance plan, treatment location, and regional geography. Antibiotics prescribed and respective course duration were also analyzed.

Results: A total of 1,937,102 coded events for finger infections, including 1,452,724 cases of cellulitis (75%), 448,548 paronychias (23%), and 35,830 felons (2%), occurred during the 5-year study period. The plurality (38%) of infections occurred in the Southern United States. Ninety-six percent of events occurred in an outpatient setting, most commonly treated by family medicine physicians, and 4% were associated with hospital admission. Seventy-two percent of claims were processed through commercial insurance, 13% through Medicaid, 12% through Medicare, and the remainder through government insurance plans or self-pay. Cephalexin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for finger cellulitis and paronychias, with a mean treatment duration of 8.6 and 8.8 days, respectively. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was prescribed more frequently than cephalexin for felons (32% vs. 30%; P < 0.01), with a mean treatment duration of 8.8 days.

Conclusion: Acute finger cellulitis, paronychias, and felons are common infections managed by a diverse group of providers in a variety of healthcare settings. Regional, insurance, and treatment differences exist. Further research is warranted to evaluate the impact of these variations and potentially refine management strategies for finger infections.

Keywords: Finger, hand infection, cellulitis, paronychia, felon.

Infections of the hand are a common pathology encountered and treated by clinicians across multiple specialties. These may arise from minor trauma, such as puncture wounds, skin breakdown, or animal bites, as well as more significant injuries, such as open fractures [1,2,3]. The severity of infection can depend, in part, upon the entry site within the hand [4]. Infections that originate in the finger tend to cross anatomic borders and travel along tendon sheaths. As a consequence, common finger infections such as cellulitis, felon, and paronychia have the capacity to rapidly progress and, therefore, their potential effects should not be underestimated [1,5]. If identified early, finger infections may be treated with elevation, warm soaks, splinting, pain management, and antibiotics. Delayed or inadequate treatment of finger infections, however, can lead to complications, including soft-tissue necrosis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and infectious tenosynovitis. More complex sequelae such as these frequently require surgical intervention and hospital admission for intravenous antibiotics [6]. Therefore, prompt identification and evidence-based treatment of finger infections is essential, particularly in populations that are more likely to experience these complications, such as diabetics, smokers, and intravenous drug users [7,8]. Furthermore, when evaluating a suspected finger infection, one should also consider inflammatory, cancerous, and rheumatic pathologies that may resemble infection [9,10]. These conditions may present similarly to superficial finger infections with pain, erythema, swelling, and decreased joint motion. Due to the vast difference in treatment recommendations across these conditions, it is essential to obtain a thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic laboratories/imaging, when appropriate, to establish an accurate diagnosis. Non-surgeon providers often manage finger infections with conservative treatments, but these infections may progress and ultimately require surgical intervention. In addition, despite the prevalence of finger infections, there is limited data on how treatment patterns have evolved in response to changes in antibiotic stewardship, healthcare access, and demographic shifts. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate national demographics and treatment patterns of finger infections. By analyzing these trends, this investigation sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiologic factors related to finger cellulitis, paronychias, and felons, and, in doing so, educate providers who treat these conditions to help mitigate their risk of progression to more complicated sequelae.

Study design and data source

This retrospective study was performed utilizing the PearlDiver patient records database and healthcare analytics platform (PearlDiver, Inc., Colorado Springs, Colo.). PearlDiver is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant database, which contains de-identified insurance claims from approximately 150 million patient records, spanning January 2010 to May 2022 [11]. All records are based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes, current procedural terminology codes, national drug codes, and prescription groupings. Claims data are collected from all U.S. states and territories, encompassing all payor types. This includes Medicare, Medicaid, commercial insurance, and self-pay. The data are verified upon entry into the database and are audited quarterly. Prior studies have employed the PearlDiver database to determine and evaluate national trends in various conditions and procedures [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Given the de-identified, aggregate nature of the data, the current study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval.

Study population

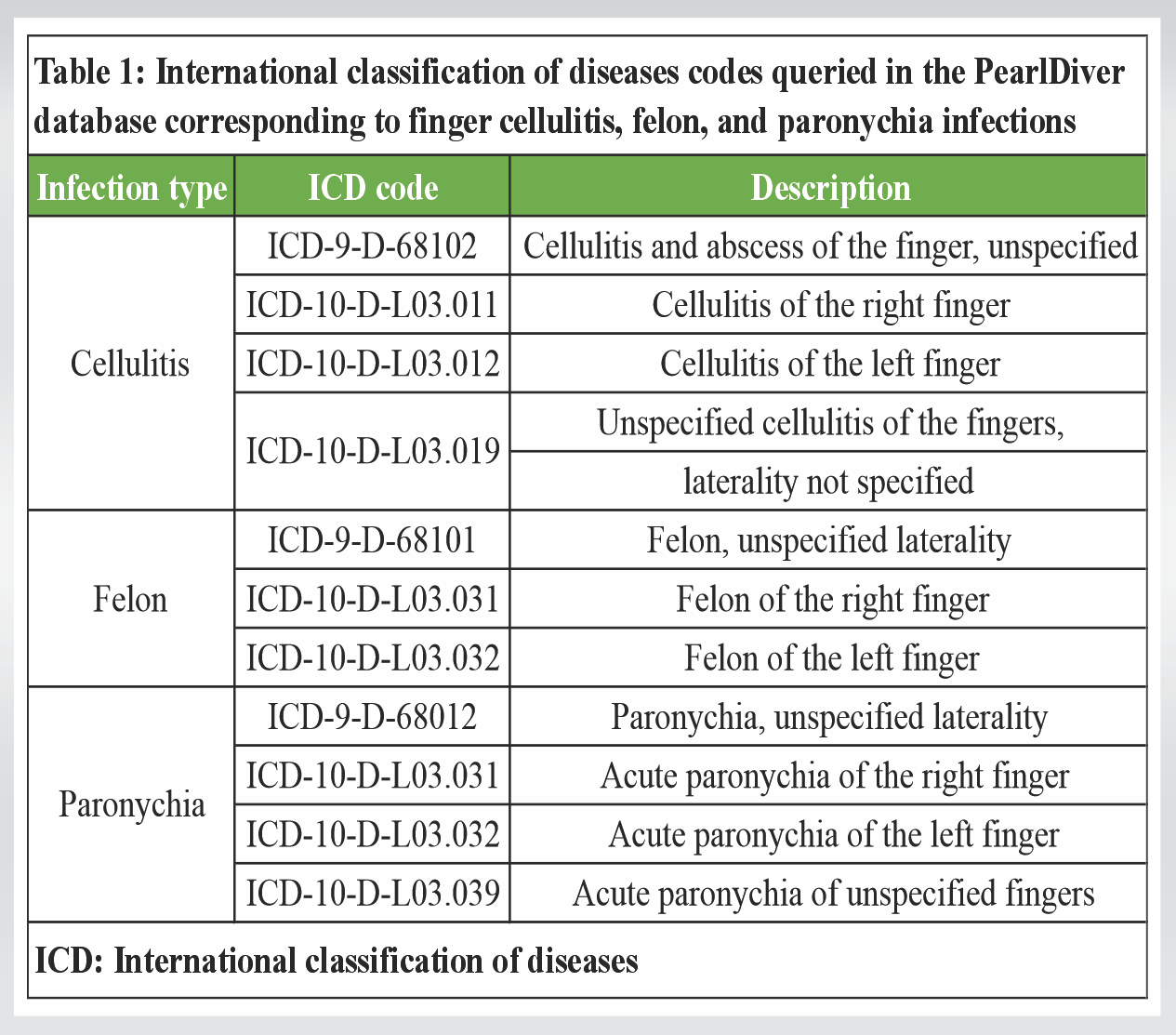

PearlDiver provides raw data that includes the following categories: Patient age, date, field number (primary, secondary, tertiary, etc.), drug group, gender, length of stay, physician specialty, physician national provider identifier, plan type, region, service location, state, and zip code. Utilizing this database, a sequence of queries was executed to identify patients who were treated for paronychia, felon, and finger cellulitis (Table 1).

Table 1: International classification of diseases codes queried in the PearlDiver database corresponding to finger cellulitis, felon, and paronychia infections

Insurance claims available for the aforementioned diagnoses spanned a 5-year period from 2010 to 2015. This reflected the subset of data available to the authors’ primary institution. Billing events associated with these diagnoses were subsequently organized by location of medical care, insurance plan, treating physician specialty, and geographic location. Antibiotics prescribed for these infections and their respective course duration were also analyzed. For each infection type, the generic drug name was grouped with the mean duration of antibiotic therapy prescribed.

Statistical analyses

Antibiotic data were listed in a comprehensive format, which permitted comparative analysis. This was performed utilizing analysis of variance testing, and all P-values are two-tailed with an alpha <0.05, indicating significance. Data pertaining to patient demographics (patient age, geographic region, and insurance coverage), treating physician specialty, and treatment location were provided in a pre-aggregated format, which did not allow for further statistical analysis. These data were analyzed using Pandas (version 1.4.2) to generate descriptive statistics across a breadth of demographic and treatment characteristics.

Demographic characteristics

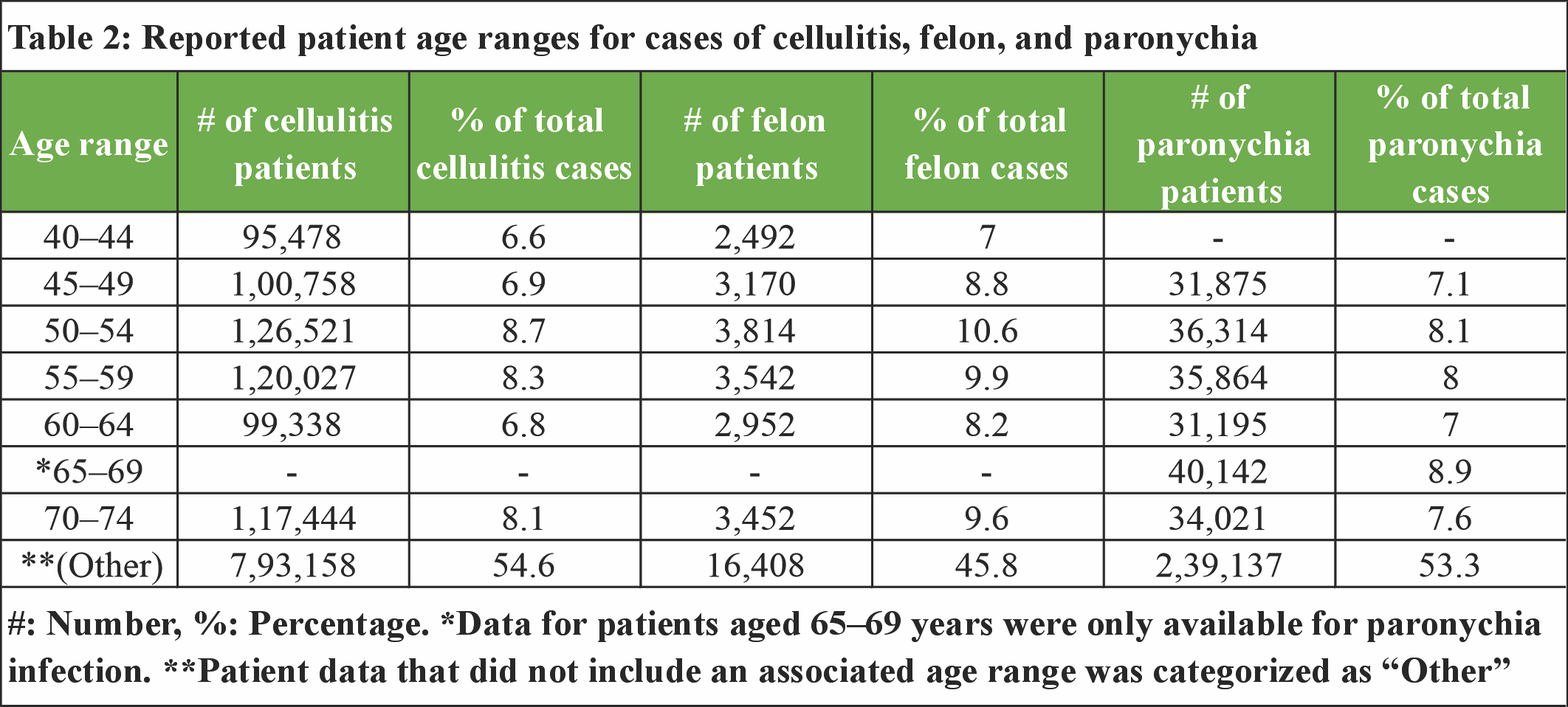

A total of 1,937,102 coded events for finger infections occurred during the study period. These included 1,452,724 cases of cellulitis (75%), 448,548 paronychias (23%), and 35,830 felons (2%). Of these patients, 55% were categorized as female and 45% were classified as male. No data regarding patient race or ethnicity were included in the dataset. The most commonly reported age range was 55–59 years for patients with cellulitis, 50–54 years for felons, and 65–69 years for paronychias (Table 2). Of note, patient data with no reported age range were categorized as “other” in Table 2.

Table 2: Reported patient age ranges for cases of cellulitis, felon, and paronychia

Geographic distribution

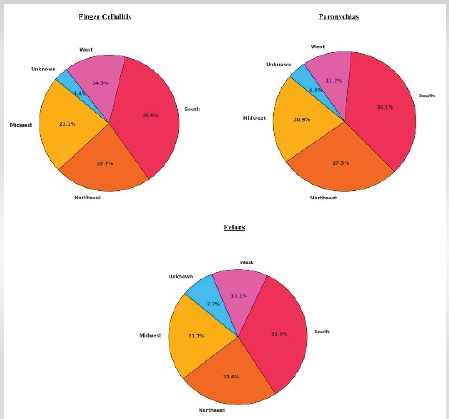

With respect to geographic distribution (Fig. 1), patient cases were reported from regions including the Midwest, Northeast, South, and West.

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of finger cellulitis, paronychias, and felons in the United States by region.

No additional stratification of states within each of these regions was provided. The relative percentage of cases in each region was comparable across all three infection types, with the plurality (36.7–37.6%) occurring in the South and the fewest (11.6–14.7%) reported in the West. A small number of cases (0.3–0.7%) were categorized as unknown regions.

Treatment settings

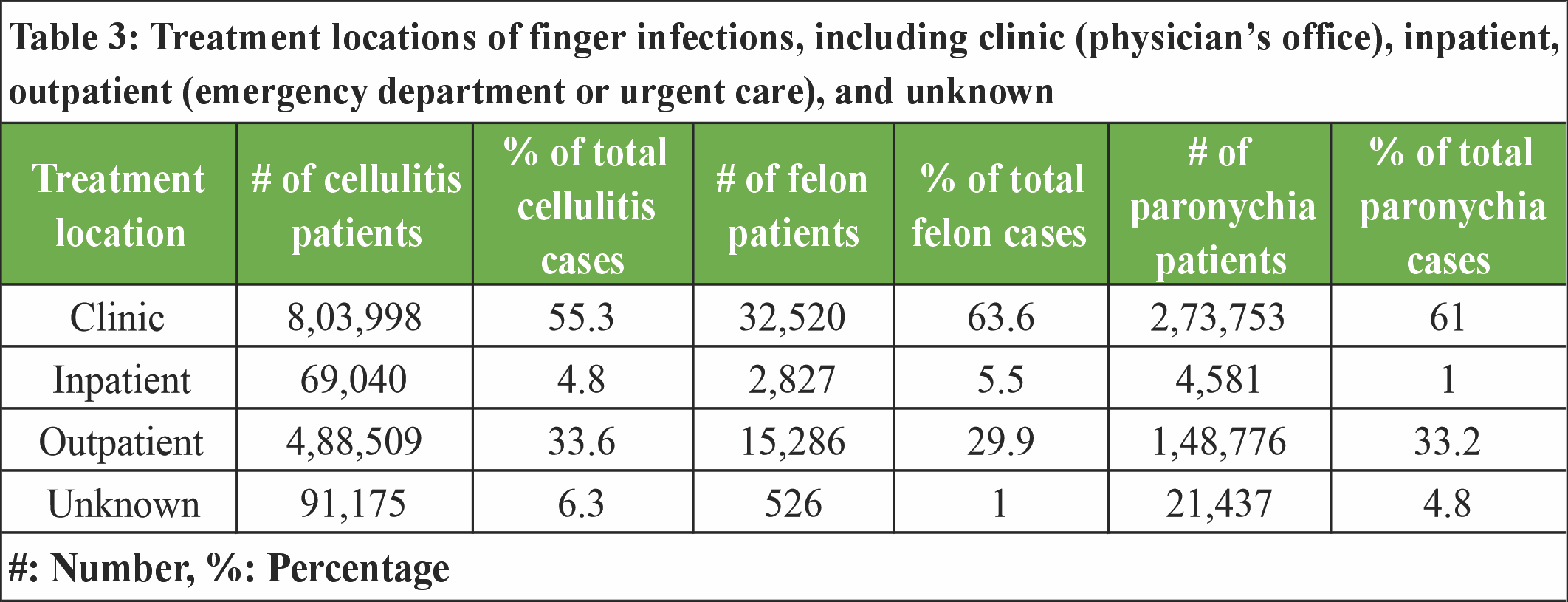

Treatment settings reported in the dataset included clinic (physician’s office), inpatient, outpatient (non-clinic outpatient settings, including emergency departments and urgent care), and unknown (Table 3).

Table 3: Treatment locations of finger infections, including clinic (physician’s office), inpatient, outpatient (emergency department or urgent care), and unknown

No further stratification was provided in the dataset. Across all three pathologies, most cases were treated in a clinic or outpatient setting, with relatively few occurring in an inpatient setting. For cellulitis, 55.3% of billing events occurred in a clinic, 33.6% in an outpatient setting, 4.8% in an inpatient setting, and 6.3% were categorized as unknown. Similarly, for felons, 63.6% of billing events occurred in a clinic setting, 29.9% in an outpatient setting, 5.5% inpatient, and 1% were categorized as unknown. In addition, for paronychia, 61% of billing events occurred in a clinic setting, 33.2% in an outpatient setting, 1% inpatient, and 4.8% were categorized as unknown.

Treating providers

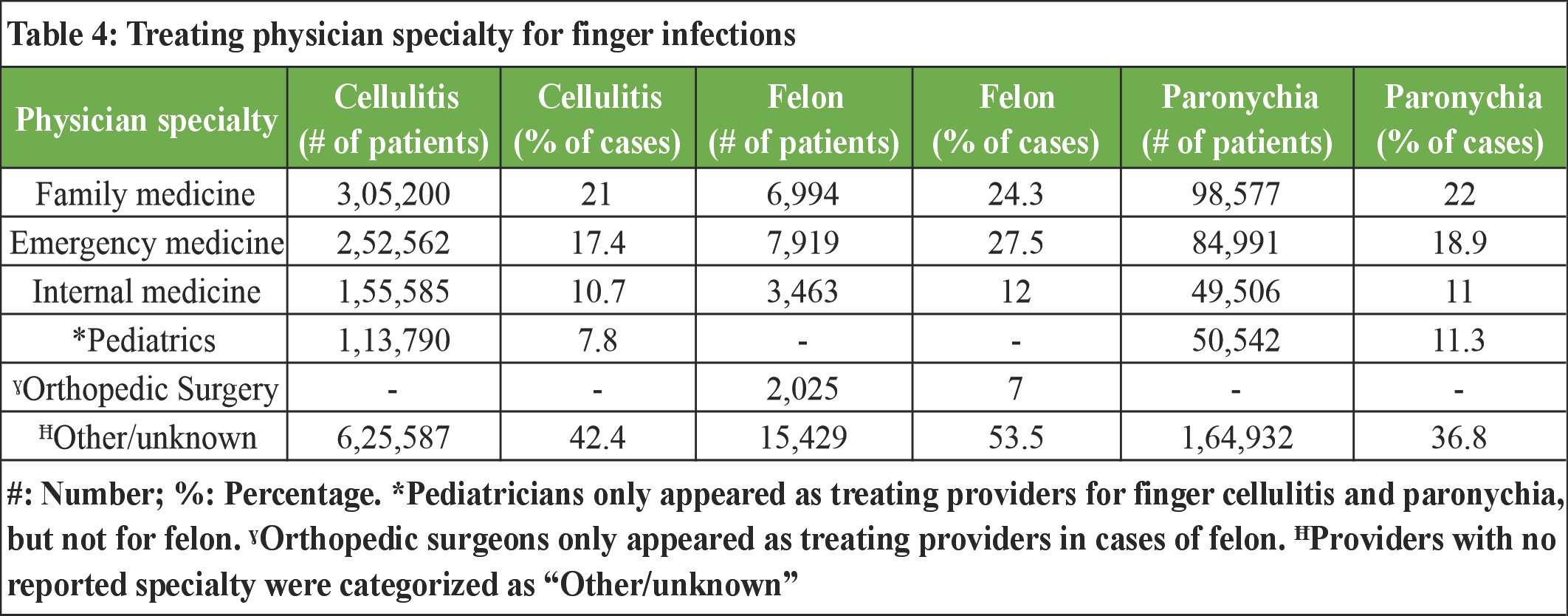

Various physician specialties contributed to the care of these infections, including family medicine, emergency medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and orthopedic surgery (Table 4).

Table 4: Treating physician specialty for finger infections

Of the specialties, family medicine physicians treated the highest percentage of finger infections (21% of cellulitis, 19.5% of felons, and 22% of paronychias), followed by emergency medicine (17.4% of cellulitis, 22.1% of felons, and 19% of paronychias) and internal medicine (10.7% of cellulitis, 9.7% of felons, 11% of paronychias). Pediatricians treated 7.8% of cellulitis cases and 11.3% of paronychias. However, pediatrics was not included as one of the treating provider types for felons. Similarly, 5.7% of felons were treated by orthopedic surgeons, but the dataset did not explicitly list orthopedic surgeons as a provider type for cellulitis or paronychia. Infections not treated by one of the aforementioned physician specialists were categorized as “Other/unknown” provider type (44% of cellulitis, 43% of felon, and 25.2% of paronychia).

Payor types

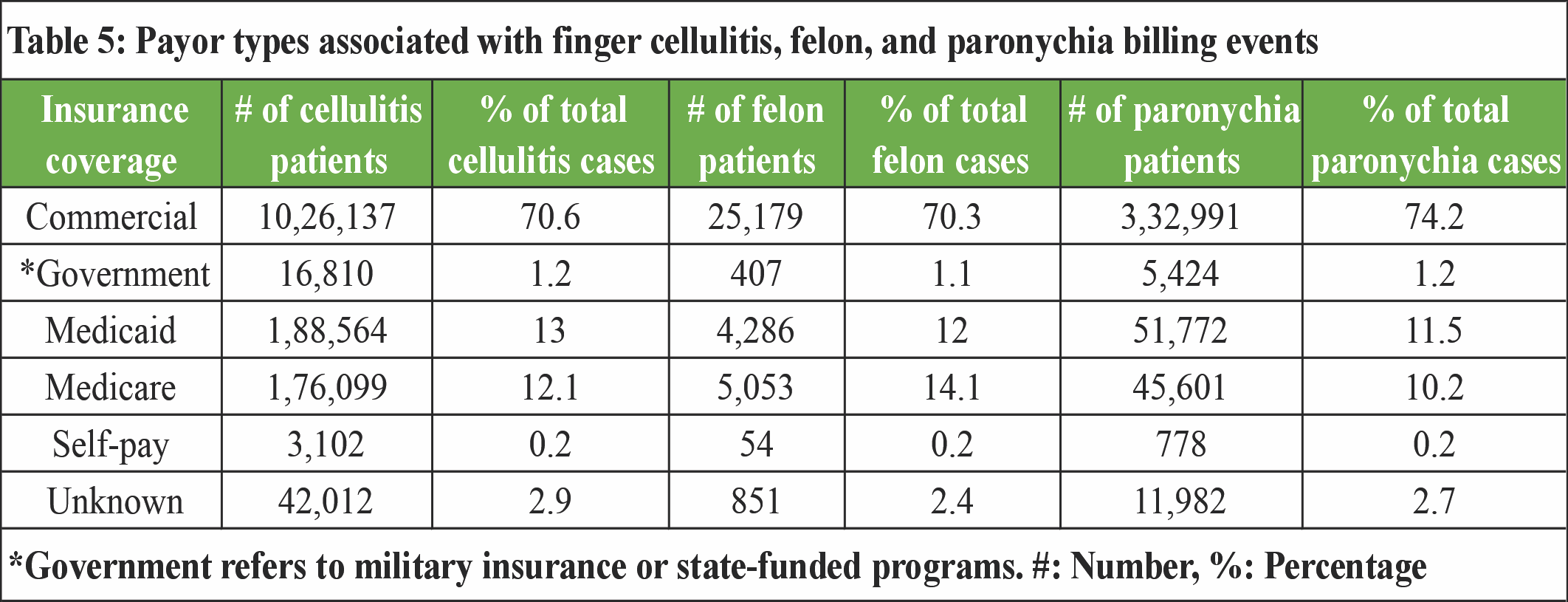

With respect to payor type, data were gathered for the following insurance coverage categories: commercial insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, Government (e.g., military insurance or state-funded programs), self-pay, and unknown (Table 5).

Table 5: Payor types associated with finger cellulitis, felon, and paronychia billing events

Commercial insurance was the most commonly utilized across all infections/billing events (70.6% of cellulitis cases, 70.3% of felon, and 74.2% of paronychia). This was followed by Medicaid (13% of cellulitis, 12% of felon, and 10.2% of paronychia), Medicare (12.1% of cellulitis, 14.1% of felon, and 10.2% of paronychia), government insurance (1.2% of cellulitis, 1.1% of felon, and 1.2% of paronychia) and self-pay (0.2% of cellulitis, 0.2% of felon, and 0.2% of paronychia). The remainder of the cases were categorized as “unknown” payor type.

Antibiotic management

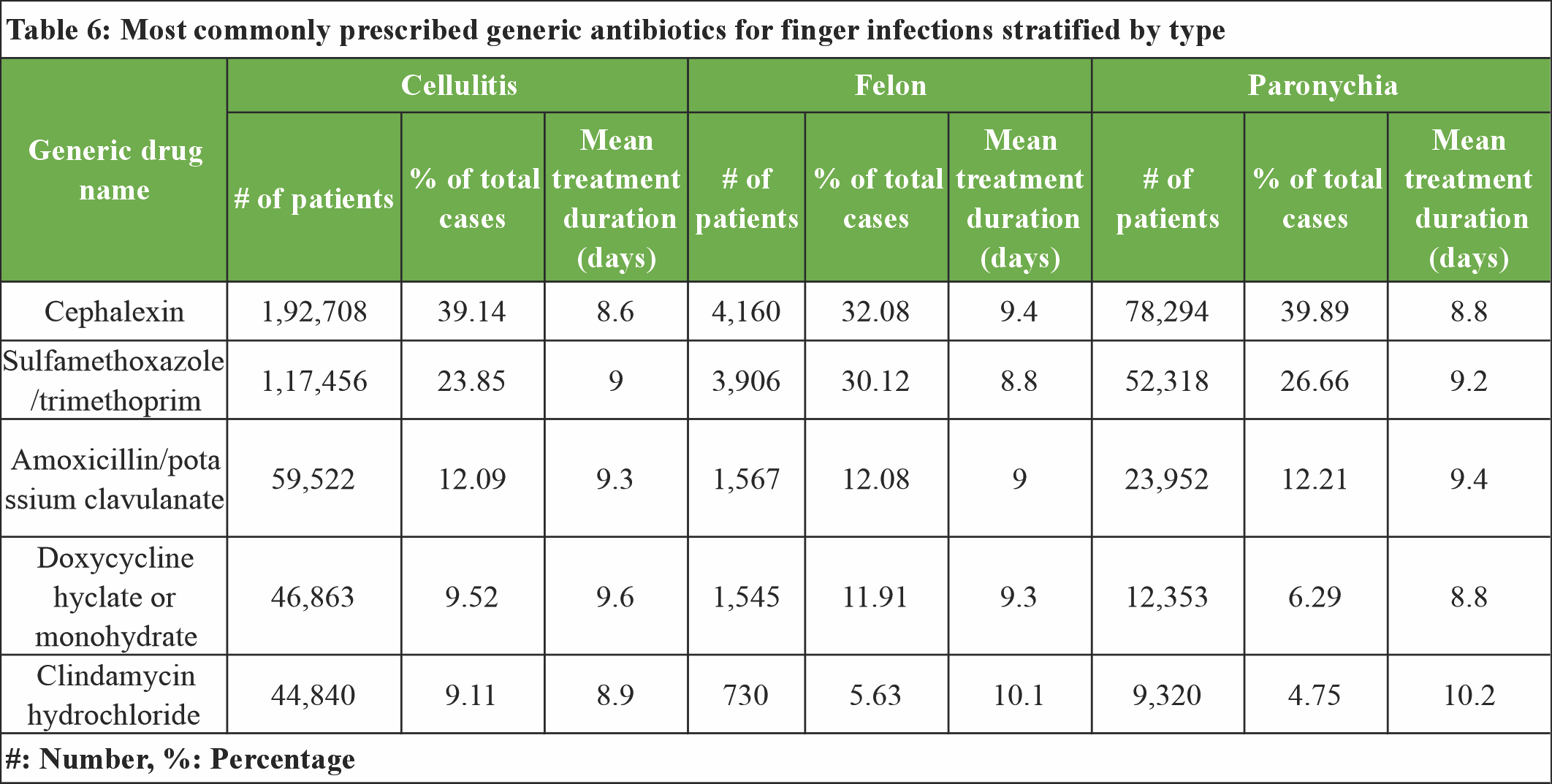

A total of 37 unique antibiotics were prescribed to treat cellulitis, 18 for felons, and 35 for paronychias. As noted in Table 6, across all three infection types, the five most commonly prescribed antibiotics were cephalexin (39.1% of cellulitis, 30.1% of felon, and 39.9% of paronychia), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (23.9% of cellulitis, 32.1% of felon, and 26.6% of paronychia), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (12.1% of cellulitis, 11.9% of felon, and 12.2% of paronychia), clindamycin (9.1% of cellulitis, 12.1% of felon, and 6.3% of paronychia), and doxycycline hyclate or monohydrate (7.2% of cellulitis, 5.6% of felon, and 4.8% of paronychia).

Table 6: Most commonly prescribed generic antibiotics for finger infections stratified by type

Cephalexin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for both cellulitis and paronychia, with a mean treatment duration of 8.6 and 8.8 days, respectively. In the case of felons, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole was most commonly prescribed (32.1%), followed by cephalexin (30.1%) (P < 0.01), with a mean treatment duration of 9.4 days.

This analysis provides an overview of patient demographics and treatment patterns for finger infections, including cellulitis, paronychias, and felons, over a 5-year period. By leveraging the PearlDiver database, this study highlights trends and gaps in the management of these infections. Within this dataset, 1.9 million cases of finger infection were identified, with the most common coded as cellulitis, followed by paronychia and felon. Across all infection types, encounters occurred most frequently in female patients in a clinic setting in the Southern United States, and were treated by either family medicine or emergency medicine physicians. While data describing the incidence of finger infections is limited, paronychias have historically been recognized as the most common. This is inconsistent with the present study, which demonstrates that finger cellulitis was diagnosed three times more frequently than paronychia. One potential explanation for this could be misdiagnosis or incorrect coding of paronychias as cellulitis. In 2018, Li et al. reported that, of 116 patients who were initially diagnosed with presumed cellulitis in the emergency department, 39 (33%) were later found to have pseudo-cellulitis (a condition mimicking the symptoms of cellulitis) [18]. Similarly, a 2011 comparative study by David et al. found that 20–28% of patients who received an initial cellulitis diagnosis later received a different diagnosis when seen by a dermatologic specialist [19]. Like cellulitis, paronychia presents with symptoms such as erythema, pain, and swelling, which may mimic cellulitis, leading to misdiagnosis [20]. Although paronychia is a common finger infection, cellulitis is among the most prevalent bacterial skin infections in the United States [21]. Its frequent occurrence may contribute to availability bias, leading less experienced clinicians to over-diagnose finger infections as cellulitis [22]. The setting in which finger infections are treated and the provider’s experience may impact diagnostic accuracy and proper coding. In the present study, the majority of infections were treated by non-hand specialists such as family medicine, emergency medicine, and internal medicine physicians, whereas many others were categorized under the specialty “other.” No further detail was provided for this category, or whether it includes non-physician providers such as advanced practice providers (APPs). A recent study analyzing Medicare claims found that one-quarter of all healthcare visits are conducted by APPs [23]. In emergency departments and primary care settings, it is common for APPs to treat low-acuity conditions independently. In a 2020 study by Pines et al., the impact of APP staffing in emergency departments nationally was analyzed over a 4-year period [24]. They found that APPs treated less complex conditions compared to physicians, allowing physicians to focus on higher-acuity conditions. Given that the majority of finger infections are uncomplicated and can be considered low acuity, it is possible that many are treated by APPs and may not be evaluated by a physician. Furthermore, data showed minimal involvement of (orthopedic) surgeons, suggesting that most cases may not be severe enough to require surgical intervention. Given the lack of unique patient identifiers, it is also possible that follow-up encounters leading to surgical interventions were not captured in the dataset. Nonetheless, it highlights the importance of training primary care and emergency medicine providers to treat uncomplicated finger infections in order to prevent complications that require involvement of a surgical specialist.

Demographics and geographic distribution

All three finger infection types occurred more frequently in female patients. Prior literature suggests that women are more likely to develop paronychia due to nail trauma during manicures or work that requires their hands to be submerged in water, such as dishwashers or cleaning staff [25,26]. This is in contrast to a recent study by Lemme et al. that focused on finger infections in the emergency department setting, in which significantly more men developed finger infections compared to women, with an incidence ratio of 1.4 [27]. The inclusion of other treatment settings in addition to the emergency department in our analysis may contribute to this discrepancy, but there is no consensus in the literature regarding the role of gender in the development of finger infections. The distribution of finger infection cases showed notable regional differences between the Midwest, Northeast, South, and West. The percentage of cases between cellulitis, paronychia, and felon was relatively similar, with the highest percentage reported in the South, followed by the Northeast and Midwest. This is consistent with prior studies. In a large database study by Peterson et al. evaluating finger cellulitis and abscesses, the authors found that the incidence of infection is highly seasonal, and the risk of hospital admission is strongly associated with warmer weather [28]. Another study by Tande et al. analyzed cases of lower extremity cellulitis across three different climates in the United States, including hot desert, humid subtropical, and humid continental [29]. Similarly, they found that the incidence of lower extremity cellulitis correlated with environmental temperature and more humid climates. This is consistent with the present findings, which demonstrate a higher rate of infection in the Southern United States.

Treatment patterns

The majority of finger infections were managed in a clinic setting, suggesting that most simple finger infections do not result in hospital admission (or are not diagnosed during admission for another medical issue) and can be managed on an outpatient basis. Notably, all surgery specialists were categorized as “orthopedic surgeons,” a potential limitation in how provider specialties are coded by insurance or reported to the PearlDiver database. In a 2022 surgical outcomes study assessing surgery practice patterns, 71.3% of hand surgeries were performed by orthopedic surgeons, 19.6% by plastic surgeons, and 9.1% by general surgeons [30]. All hand specialists in the outcomes study performed surgery to treat hand infections, but hand infection surgeries represent a small percentage relative to the other procedures performed by orthopedic and plastic hand surgeons (0.8% and 1.5%, respectively). In contrast, 43% of hand surgeries performed by general surgeons were related to hand infection. With respect to insurance coverage, over 70% of reported finger infections occurred in individuals with commercial insurance, and <0.2% of cases occurred in patients who were self-pay. This disparity highlights a barrier to the treatment of finger infections in uninsured patients, as these individuals are less likely to seek care over financial concerns. This may lead uninsured patients to delay care during the early stages of infection. Although uncomplicated finger infections can typically be treated conservatively, uninsured individuals may be more likely to experience delays in treatment and subsequent complications.

Implications for clinical practice

Accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment of finger infections are essential to prevent the spread of infection, which may necessitate more invasive treatment, hospital admission, and potential long-term disability. The results of the current study indicate that the majority of finger infections are managed in the outpatient clinic setting, indicating that hospital admission is typically not required for the treatment of finger infections. However, as noted by the discrepancy between the PearlDiver dataset (in which finger cellulitis was, by far, the most commonly coded infection) and the historical recognition that paronychias are the most common finger infection, misdiagnosis due to coding inconsistencies may be common among finger infections. This can lead to inappropriate treatment, progression of infection, and poor patient outcomes. Accurate diagnosis is also crucial to minimize overutilization of healthcare resources, such as laboratory tests or imaging.

Limitations

This study is not without its limitations. The use of pre-aggregated claims data limits access to detailed patient-level information, including clinical outcomes, complications, infection severity, and laboratory findings. Critical factors such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, which are essential for understanding healthcare disparities, are also absent. Coding inaccuracies may introduce misclassification, while reliance on billing data without original patient records makes it difficult to validate the findings. Surgeon specialties may also be categorized in many ways, including by board certification or the service line they are appointed to within a healthcare system. For example, a plastic hand surgeon may be incorrectly classified as an orthopedic or general surgeon depending upon the department in which they are hired or how these data are reported to insurance providers. In addition, the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria for conditions such as paronychias, felons, and finger cellulitis leads to variability in diagnosis and treatment. This introduces further variability in diagnosis and adherence to guidelines, impacting the reliability and generalizability of the results.

This study highlights the significant burden of finger infections on the healthcare system and identifies opportunities for improving care delivery. Specifically, it demonstrates that non-surgical providers most frequently diagnose and manage these conditions. Considering this, educating providers in medical specialties (e.g., primary care or emergency medicine) to care for these conditions is important to help mitigate the progression of uncomplicated finger infections and minimize the need for surgical intervention by hand specialists. Further research is warranted to evaluate the impact of these findings and refine both educational efforts and management strategies for finger infections.

Acute finger cellulitis, paronychias, and felons are common infections managed by a diverse group of providers in a variety of healthcare settings. Regional, insurance, and treatment differences exist. Educating non-surgical providers to treat these conditions can help mitigate the risk of progression to more complicated sequelae.

References

- 1. Ong YS, Levin LS. Hand infections. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:225e-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Rerucha CM, Ewing JT, Oppenlander KE, Cowan WC. Acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician 2019;99:228-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Osterman M, Draeger R, Stern P. Acute hand infections. J Hand Surg Am 2014;39:1628-35; quiz 1635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Dastagir K, Vehling M, Könneker S, Bingoel AS, Kaltenborn A, Jokuszies A, et al. Spread of hand infection according to the site of entry and its impact on treatment decisions. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2021;22:318-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Koshy JC, Bell B. Hand infections. J Hand Surg Am 2019;44:46-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Luginbuhl J, Solarz MK. Complications of hand infections. Hand Clin 2020;36:361-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Houshian S, Seyedipour S, Wedderkopp N. Epidemiology of bacterial hand infections. Int J Infect Dis 2006;10:315-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Dailiana ZH, Rigopoulos N, Varitimidis S, Hantes M, Bargiotas K, Malizos KN. Purulent flexor tenosynovitis: Factors influencing the functional outcome. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2008;33:280-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chui CH, Lee JY. Diagnostic dilemmas in unusual presentations of gout. Aust Fam Physician 2007;36:931-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Flevas DA, Syngouna S, Fandridis E, Tsiodras S, Mavrogenis AF. Infections of the hand: An overview. EFORT Open Rev 2019;4:183-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Ratnasamy PP, Diatta F, Allam O, Kauke-Navarro M, Grauer JN. Risk of postoperative complications after total hip and total knee arthroplasty in Behcet syndrome patients. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2024;8:e24.00040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Gouzoulis MJ, Seddio AE, Rancu A, Jabbouri SS, Moran J, Varthi A, et al. Trends in management of odontoid fractures 2010-2021. N Am Spine Soc J 2024;20:100553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Forlenza EM, Serino J, Shinn D, Gerlinger TL, Valle CJ, Nam D. No difference in postoperative complications between simultaneous and staged, bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2025;38:201-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Kozyra M, Kostyun R, Strecker S. The prevalence of multisystem diagnoses among young patients with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder: A retrospective analysis using a large healthcare claims database. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024;103:e39212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Halperin SJ, Dhodapkar MM, McLaughlin WM, Hewett TE, Grauer JN, Medvecky MJ. Rate and timing of revision and contralateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction relative to index surgery. Orthop J Sports Med 2024;12:23259671241274671 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Lasorsa F, Orsini A, Bignante G, Bologna E, Licari LC, Lambertini L, et al. Living donor nephrectomy: Analysis of trends and outcomes from a contemporary national dataset. Urology 2025;195:36-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Harkin W, Berreta RS, Williams T, Turkmani A, Scanaliato JP, McCormick JR, et al. The effect of surgeon volume on complications after total shoulder arthroplasty: A nationwide assessment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2025;34:1112-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, Dewan AK, Pallin DJ, Baugh CW, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:537-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, Ladrigan M, Papier A, Miller LG, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J 2011;17:1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Clark DC. Common acute hand infections. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:2167-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Stulberg DL, Penrod MA, Blatny RA. Common bacterial skin infections. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:119-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Mamede S, Van Gog T, Van Den Berge K, Rikers RM, Van Saase JL, Van Guldener C, et al. Effect of availability bias and reflective reasoning on diagnostic accuracy among internal medicine residents. JAMA 2010;304:1198-203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Patel SY, Auerbach D, Huskamp HA, Frakt A, Neprash H, Barnett ML, et al. Provision of evaluation and management visits by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the USA from 2013 to 2019: Cross-sectional time series study. BMJ 2023;382:e073933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Pines JM, Zocchi MS, Ritsema T, Polansky M, Bedolla J, Venkat A, et al. The impact of advanced practice provider staffing on emergency department care: Productivity, flow, safety, and experience. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:1089-99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Dulski A, Edwards CW. Paronychia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Leggit JC. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician 2017;96:44-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Lemme NJ, Li NY, Testa EJ, Kuczmarski AS, Modest J, Katarincic JA, et al. A nationwide epidemiological analysis of finger infections presenting to emergency departments in the United States from 2012 to 2016. Hand (N Y) 2022;17:302-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Peterson RA, Polgreen LA, Sewell DK, Polgreen PM. Warmer weather as a risk factor for cellulitis: A population-based investigation. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1167-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Tande A, Baddour LM, Marcelin JR, O’horo J. Seasonal and environmental variation of lower extremity cellulitis incidence among emergency department patients in three geographic locations. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017;4 Suppl 1:S113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Drinane JJ, Drolet B, Patel A, Ricci JA. Residency training and hand surgery practice patterns: A national surgical quality improvement program database analysis. J Hand Microsurg 2020;14:132-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]