In limb impalement injuries, controlled operative extraction with direct visualization, anatomical plane respect, and neurovascular preservation yield excellent outcomes, even in severe cases.

Dr. Aditya A Agarwal, Department of Orthopedics, Grant Government Medical College and Sir JJ Group of Hospitals, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dradiagr@gmail.com

Introduction: Impalement injuries of the upper limb represent a rare and striking form of penetrating trauma, often associated with significant risk of neurovascular and tendinous damage due to the compact anatomical arrangement of the forearm. Despite their alarming external appearance, actual morbidity is determined by the trajectory relative to critical structures. Effective management requires careful pre-hospital stabilization, thorough pre-operative assessment, appropriate imaging, and meticulous surgical extraction under direct visualization to minimize complications.

Case Report: A 29-year-old male presented with a trans-forearm impalement injury sustained after falling over a metal gate while under the influence of alcohol. The iron rod, approximately one inch in diameter, entered the volar aspect of the left forearm and exited dorsally near the base of the thumb. Emergency responders appropriately shortened the rod in situ with an angle grinder to facilitate transport without removing it. On arrival, the patient was hemodynamically stable, with intact motor and sensory function in the radial, median, and ulnar nerve distributions, and palpable distal pulses. Plain radiographs confirmed absence of fractures or bony involvement. Surgical exploration under general anesthesia revealed that the rod traversed a superficial subcutaneous plane, sparing major neurovascular structures and tendons. Controlled extraction under direct vision was performed without complication. The wound was irrigated thoroughly with normal saline, povidone-iodine, and hydrogen peroxide, and closed over a glove drain. The patient received broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis per protocol. Post-operative recovery was uneventful, with full preservation of neurovascular function and a complete range of motion at discharge on post-operative day ten and at subsequent follow-up.

Conclusion: This case highlights the critical importance of adhering to established trauma management principles in impalement injuries, including stabilization at the scene, avoidance of pre-mature removal, comprehensive pre-operative evaluation, and extraction under direct visualization. Despite the dramatic presentation, the foreign body followed a superficial trajectory that spared vital structures, resulting in an excellent functional outcome. This report contributes to the limited literature on upper limb impalement with complete neurovascular preservation and underscores the need for a structured, anatomy-respecting, multidisciplinary approach to optimize patient outcomes in such complex trauma scenarios.

Keywords: Upper limb trauma, impalement injury, forearm, neurovascular preservation, surgical extraction.

Impalement injuries represent a dramatic and rare subset of penetrating trauma, involving a foreign object forcibly entering and remaining embedded in the body. Although such injuries may appear severe, their actual morbidity depends on the involved anatomical structures and trajectory. Most impalement injuries are the result of high-energy mechanisms such as falls, road traffic accidents, construction site injuries, or assaults involving metallic or wooden objects [1,2]. While impalement of the torso and lower limbs has been more frequently reported, upper limb impalement remains infrequent, with only sporadic case reports available in the literature [3,4]. The forearm, being a compact region with a dense anatomical arrangement of bones, tendons, nerves (radial, ulnar, median), and major arteries (radial and ulnar), is particularly vulnerable to functional loss even from low-energy injuries. Penetrating trauma in this region often results in significant damage, requiring complex reconstruction, prolonged rehabilitation, and occasionally permanent disability [5]. The core principles in managing such injuries include non-removal of the foreign object outside a controlled surgical environment, early broad-spectrum antibiotic administration, appropriate imaging for surgical planning, and extraction under direct visualization with meticulous preservation of vital structures [6]. Timely and structured surgical exploration is critical, especially in resource-limited settings where advanced imaging may be unavailable or delayed. Our case describes a rare instance of trans-forearm impalement in which, despite the apparently perilous entry and exit wounds, all neurovascular and tendon structures were preserved. Such cases underscore the importance of not assuming severity based solely on visual presentation and highlight the value of careful, protocol-driven management.

A 29-year-old male was brought to the emergency department following accidental impalement of the left forearm by an iron rod (Fig. 1). The injury occurred while the patient was under the influence of alcohol and involved a fall over a metal gate in the Ambarnath industrial area. The rod was approximately 1 inch in diameter and had entered the volar forearm and exited dorsally near the base of the thumb. The rod was cut at the scene with an angle grinder by rescue personnel, and the patient was transported to our center.

Figure 1: Initial presentation of upper limb impalement injury. Clinical photograph showing the iron rod traversing the left forearm with the volar entry wound and dorsal exit near the base of the thumb. Plain radiograph confirming the trans-forearm trajectory of the foreign body without bony involvement.

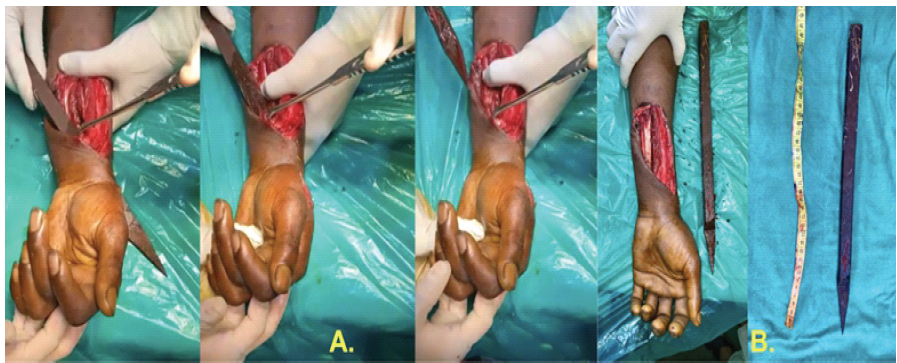

On examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and neurologically intact. Entry wound on the volar aspect measured 8 × 5 cm, and the exit wound on the dorsum of the hand measured approximately 3 × 2 cm. There was no active bleeding. Sensory and motor function in the radial, median, and ulnar nerve distributions was preserved. Radial and ulnar artery pulsations were palpable (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Surgical exploration revealed the rod passing through the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the flexor tendons and neurovascular structures. Intraoperative image (a) shows rod removal under direct vision, (b) Impaled object after removal

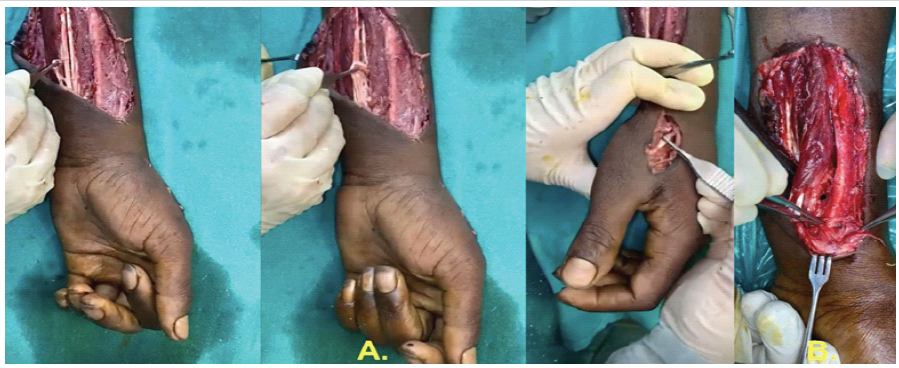

The patient was taken to the operating room for wound exploration under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, the rod was found traversing the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor carpi radialis, and palmaris longus, and above the dorsal interossei muscles. None of the neurovascular structures or tendons were injured (Fig. 3). The rod was carefully removed under direct vision. The wound was extensively irrigated with normal saline, betadine, and hydrogen peroxide. Hemostasis was achieved, and skin closure was done with Ethilon 3–0 sutures over a glove drain.

Figure 3: Intraoperative findings and assessment. Showing (a) intact flexor tendon function and (b) preserved neurovascular integrity post-rod removal.

The post-operative period was uneventful. The patient retained a full range of motion at the wrist and fingers. No signs of infection or compartment syndrome were observed. The patient was discharged on post-operative day 10 and followed up in the outpatient department with satisfactory wound healing and preserved limb function.

Impalement injuries are rare but potentially devastating forms of penetrating trauma. Their severity stems not just from the energy involved but from the complexity of anatomical structures encountered, particularly in the upper limb. Our case is noteworthy for the complete sparing of critical structures despite a trans-forearm trajectory – an uncommon and fortunate outcome.

Pre-hospital considerations and initial evaluation

The first principle in managing impalement injuries is non-removal of the object at the scene, as emphasized in the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines and multiple case-based studies. Removal can precipitate catastrophic bleeding by releasing the tamponade effect and may cause further soft tissue or neurovascular damage [5]. The object must be stabilized, shortened if necessary for transport, and the patient transferred to a trauma facility. Our patient’s impaled rod was cut in situ by first responders, allowing safe transport. However, minimal manipulation and preservation of the original trajectory during transport remain vital. On arrival, the primary survey should follow ATLS protocols, with special attention to circulatory stability and limb perfusion. In extremity trauma, detailed documentation of distal pulses, motor power, capillary refill, and sensory function is essential, as injuries may initially be occult or masked by pain [7].

Imaging and pre-operative planning

Initial imaging typically involves plain radiographs to determine the trajectory and exclude fractures, as done in our case. While X-rays suffice in many cases, computed tomography (CT) or CT angiography (CTA) becomes crucial when:

- The trajectory is near major vessels

- There are absent or diminished distal pulses

- Neurological deficits are noted

- The object is large, complex, or deeply embedded.

CTA is considered the gold standard for diagnosing vascular injuries in penetrating extremity trauma and can detect partial vessel wall injuries, pseudoaneurysms, or occlusions not evident on clinical examination [8].

Surgical approach and extraction under direct vision

Surgical management must allow safe extraction under direct visualization. Multiple authors have stressed the importance of using incisions that connect entry and exit wounds, allowing controlled dissection and minimizing further trauma [9]. In our case, the rod passed superficially in the subcutaneous plane, sparing the flexor tendons, radial and ulnar arteries, and median/ulnar nerves – a truly rare finding. The object was removed under vision without traction or blind manipulation, thereby avoiding iatrogenic injury. Ketterhagen and Wassermann first proposed the “fistulotomy” approach to incise along the tract of the object for controlled removal [10].

Infection prevention: Irrigation, debridement, and antibiotics

One of the cornerstones of impalement injury management is copious irrigation to prevent infection. Soil and rust contaminants carried by iron rods increase the risk of polymicrobial infections, including anaerobes and rare soil organisms. In our case, irrigation with normal saline, povidone-iodine, and hydrogen peroxide was performed. This is consistent with recommendations that advise high-volume lavage with saline and avoidance of soap or topical antibiotics, which may impair tissue healing [11]. Administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics at admission and continuation for 3–5 days post-operatively is advised, particularly for contaminated or deep injuries [12]. Tetanus immunoprophylaxis must be administered as per CDC guidelines, especially in cases with unknown or incomplete immunization history [13].

Post-operative care and rehabilitation

Close monitoring in the post-operative period is vital. Although our patient had an uneventful recovery, clinicians must remain vigilant for:

- Infection (especially in deep tracts)

- Compartment syndrome (especially in deep muscular impalement)

- Delayed vascular compromise, and

- Residual foreign body fragments.

Early mobilization is beneficial when tendon or skeletal injury is absent. Functional recovery is best preserved when rehabilitation is initiated promptly, avoiding stiffness and tendon adhesions. Our patient regained full wrist and finger motion by follow-up, consistent with best-case outcomes [14]. Only a handful of upper limb impalement cases with complete neurovascular and tendon preservation have been reported. Most cases involve at least partial injury to flexor tendons, digital nerves, or arteries requiring repair or reconstruction. Our case illustrates the anatomical unpredictability of impalement injuries; despite apparent severity and long trajectory, the object can traverse non-critical planes. It reinforces the value of controlled exploration and underscores that visual appearance alone is not predictive of severity. Management of impalement injuries requires a structured approach involving multidisciplinary coordination, meticulous surgical planning, and attention to neurovascular integrity. While these injuries often imply severe morbidity, early intervention, controlled extraction under direct vision, and standardized protocols can yield outstanding outcomes, as seen in our case.

Upper limb impalement injuries are rare but potentially complex due to the dense concentration of neurovascular and tendon structures in a confined space. While the external appearance may suggest severe internal damage, as shown in our case, a superficial trajectory can result in unexpectedly minimal injury. This emphasizes the importance of careful pre-operative assessment, preservation of the impaling object until operative extraction, and surgical removal under direct vision. With timely intervention, appropriate imaging, and multidisciplinary coordination, favorable outcomes – including complete functional recovery – are possible even in dramatic presentations. Our case adds to the limited literature and reinforces the value of a structured, anatomy-respecting approach in trauma care.

In cases of limb impalement, controlled operative extraction and direct visualization during removal are critical. Even seemingly devastating injuries can have excellent outcomes if anatomical planes are respected and neurovascular structures are preserved.

References

- 1. Horowitz MD, Ochsner JL. Impalement Injuries. Ann Thorac Surg 1987;44:676-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kelly IP, Attwood SE, Quilan W, Fox MJ. The management of impalement injury. Injury 1995;26:191-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. James J. Pediatric forearm impalement injury: A case report with review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2023;13:71-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Scaglia M, Negri S, Pellizzari G, Amarossi A, Pasquetto D, Samaila EM, et al. Impalement injuries of the shoulder: A case report with literature review. Acta Biomed 2021;92 Suppl 3:e2021565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Frykberg ER, Dennis JW, Bishop K, Laneve L, Alexander RH. The reliability of physical examination in the evaluation of penetrating extremity trauma for vascular injury: Results at one year J Trauma 1991;31:502-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Banshelkikar SN, Sheth BA, Dhake RP, Goregaonkar AB. Impalement injury to thigh: A case report with review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2018;8:71-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Mavrogenis AF, Panagopoulos GN, Kokkalis ZT, Koulouvaris P, Megaloikonomos PD, Igoumenou V, et al. Vascular injury in orthopedic trauma. Orthopedics 2016;39:249-59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Pieroni S, Foster BR, Anderson SW, Kertesz JL, Rhea JT, Soto JA. Use of 64-row multidetector CT angiography in blunt and penetrating trauma of the upper and lower extremities. Radiographics 2009;29:863-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Newton EJ, Love J. Acute complications of extremity trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2007;25:751-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ketterhagen JP, Wassermann DH. Impalement injuries: The preferred approach. J Trauma 1983;23:258-9 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Anglen JO. Comparison of soap and antibiotic solutions for irrigation of lower-limb open fracture wounds. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:1415-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Zalavras CG, Patzakis MJ, Holtom PD, Sherman R. Management of open fractures. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2005;19:915-29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tetanus. Atlanta: CDC; 2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Patil RK, Koul AR. Early active mobilisation versus immobilisation after extrinsic extensor tendon repair: A prospective randomised trial. Indian J Plast Surg 2012;45:29-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]