This case underscores the significance of recognizing the sacroiliac joint as a potential pain source in cases of recurrent radiculopathy post-lumbar spine surgery, with endoscopic sacroiliac joint ablation emerging as an innovative therapeutic option, expanding treatment possibilities for spine surgeons in post-operative management challenges.

Dr. Sagar Kishor Kokate, Department of Spine Surgery, Indore Spine Centre and Care CHL Hospital, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: dr.sagarkokateortho@gmail.com

Introduction: Low back pain persisting after spine surgery presents diagnostic and treatment complexities for spine surgeons. Failed back syndrome is a term usually used to characterize chronic back or leg pain following spine surgery. Research has indicated a range of persistent pain occurrences after spine surgery. The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) has been recognized as a potential source of pain for a long time but has not received sufficient attention in subsequent years. Dysfunctions in the SIJ can result in a spectrum of clinical conditions, such as low back pain and lower limb radiculopathy. Traditional treatment approaches for SIJ disorders often involve conservative measures such as physical therapy, medications, intra-articular injections, and surgical options. In the past decade, endoscopic SIJ ablation has emerged as a minimally invasive alternative for managing SIJ pain and dysfunction. This approach combines minimal invasiveness with precise targeting, potentially reducing morbidity and enabling quicker recovery compared to open surgical procedures.

Case Report: A 60-year-old female patient with grade 2 L5-S1 lytic listhesis initially underwent lumbar interbody fusion to address chronic low back pain and radiculopathy, resulting in significant symptom resolution for a brief period. The patient experienced a resurgence of symptoms within a short duration that proved refractory to conventional medical management and interventional pain management procedures. Ultimately, the patient achieved sustained relief after undergoing endoscopic SIJ ablation

Conclusion: This case report highlights the importance of endoscopic SIJ ablation as an innovative treatment for recurrent lower limb radiculopathy. Focusing on the SIJ, often neglected in lumbar spine surgery, this minimally invasive procedure shows promise in alleviating symptoms and enhancing patient outcomes.

Keywords: Recurrent radiculopathy, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, endoscopic sacroiliac joint ablation, failed back surgery syndrome.

Lytic spondylolisthesis, a condition characterized by the slippage of one vertebra over another, is known to cause a spectrum of symptoms that primarily involve the lumbar spine. On the other hand, sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction is often associated with pelvic and lower back pain. What makes these conditions particularly intriguing and challenging is the potential for their symptoms to overlap, leading to diagnostic ambiguity and clinical complexity. Dysfunctions in the SIJ can result in a spectrum of clinical conditions. Traditional treatment approaches for SIJ disorders often involve conservative measures such as physical therapy, medications, intra-articular injections, and surgical options. Endoscopic SIJ ablation, originally developed to address SIJ pain and dysfunction, has garnered increasing attention as a potential therapeutic option for patients suffering from recurrent refractory lower limb radiculopathy. The rationale for exploring this technique lies in the intricate interplay between the SIJ and the lumbosacral nerve roots, where referral pain from the SIJ can mimic or exacerbate the symptoms of lumbar radiculopathy. Consequently, endoscopic SIJ ablation is gaining recognition for its role in managing radiculopathy that proves refractory to conventional treatments.

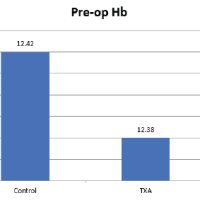

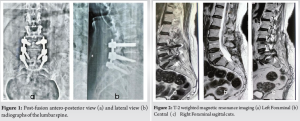

A 60-year-old female presented to us following a painless interval of 4 days after undergoing L4-L5 postero-lateral and L5-S1 interbody fusion with recurrent left-sided low back pain and left lower limb radiculopathy (Fig. 1). In view of the non-dermatomal pattern of pain and tenderness over SIJ, the patient was administered SIJ injections on the 5th day post-surgery after which the patient reported near-complete resolution of pain.

The patient subsequently had a fall 10-day post-surgery and presented at the outpatient department 2 weeks post-operatively, manifesting recurrent severe left lower limb pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 2 and 3) and X-ray assessments were repeated, and the findings did not indicate the presence of any untreated or recurring compressive factors within the lumbar spine. The predominant pain manifestation was localized to the L5 and S1 dermatome areas. Palpation of the lateral terminal branch of the deep peroneal nerve and the terminal branches of the sural nerve elicited pain. Relief of radicular pain was noted on injecting lignocaine 2% plain at the peripheral nerve endings [1].

Examination

The patient had a positive flexion abduction external rotation test. The pelvic compression and thigh thrust tests were positive. Palpation over the SIJ was tender. There was no neurological deficit. Active and passive straight leg raising produced pain. Gentle palpation over the distal ends of the deep peroneal nerve at the lateral terminal branch and sural nerve produced a pain response [1]. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score at the time was 9.

Radiology

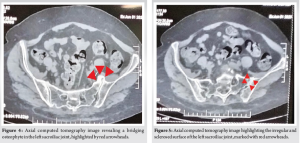

A combiscan revealed changes in the joint space of the SIJ with increased density in the subchondral bone and large osteophytes around the lower 1/5th of the joint (Fig. 4 and 5). There was no evidence of any untreated or recurring compressive factors within the lumbar spine.

Planning:

Considering the clinical evaluation, radiological assessments, and a positive response to prior SIJ injection, the identification of the SIJ as the pain generator was established. An endoscopic left SIJ ablation was planned.

Procedure

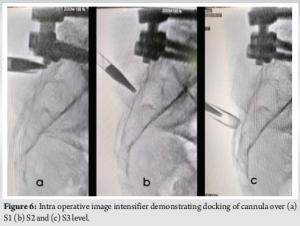

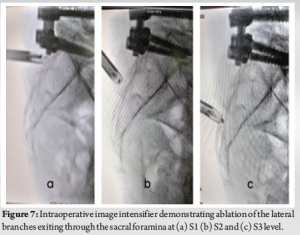

In view of the severe pain which did not allow the patient to lie down in a prone position, the procedure was done under general anesthesia. An anteroposterior fluoroscopic view was captured utilizing an image intensifier. Subsequently, a transducer was inclined cephalad by approximately 15° and obliquely tilted contralaterally by 15° to achieve optimal visualization of the foramen. The cutaneous entry point was situated at the lower aspect of the foramen. An 18-gauge needle was precisely positioned on the interosseous ligament covering the posterior SIJ. Subsequently, a guide wire was advanced through the needle, followed by the withdrawal of the needle, and a small skin incision was performed at the entry site. A beveled working cannula was advanced along the obturator until reaching the posterior aspect of SIJ (Fig. 6). Following obturator removal, the endoscope was introduced through the cannula. The ultimate placement of the cannula was validated using fluoroscopic imaging. The cannula tip was moved along the subcutaneous plane toward the region lateral to the S1–S3 sacral foramina. We attempted to visually confirm the lateral branches exiting the sacral foramina and the branches coursing toward the SIJ when possible to ensure accurate nerve ablation (Fig. 7). Using the radiofrequency (RF) ablation wand, ablation was performed from 12 o’clock to 6 o’clock (counter clockwise) from S1 to S3 (Fig. 8). Sustained saline irrigation was consistently upheld throughout the procedure to mitigate potential thermal injury to adjacent structures. Following the ablation of the specified target points, both the endoscope and cannula were subsequently withdrawn.

Post-operative management

The postoperative period was uneventful. Ambulation was initiated on the same day. The patient was discharged the next day. The patient was followed up sequentially at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks. No recurrence or new-onset symptoms were reported during the follow-up period. Post-procedure the VAS score was 2 at 6 weeks as compared to the pre-procedure score of 9.

Studies have reported a 10% – 40% incidence of persistent pain following spine surgery [2–8]. SIJ was identified as a potential pain generator in 1905 but has not been given enough attention later [9]. The SIJ is the largest axial joint in the body and serves to transmit forces from the upper body to the lower limbs [10]. Its surfaces are irregular, indicating that its function is stability rather than motion. In SIJ complex pain, patients tend to complain of buttock pain, but many experience lower leg pain on the involved side as well, which can be confused with radiculopathy or referred pain from other low back structures [11]. Lumbar spinal fusion can result in changes in the spinopelvic profile of the patient and undue stresses on the surrounding structures which include the SIJ [12]. Biomechanical studies also showed increased stress on the SIJ following lumbar fusion [13]. In 2016, Unoki et al. [14] noted a 10.7% occurrence of new-onset SIJ pain among patients who underwent lumbosacral fusion. Lee et al. [15] in 2019 identified a 12% occurrence of new-onset SIJ pain subsequent to fusion. Managing SIJ pain poses challenges, with therapies categorized as addressing underlying pathology or alleviating symptoms. Limited evidence results from a lack of controlled outcome studies. Initial treatment involves conservative approaches such as physical therapy, chiropractic care, and medical therapy, including Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain relief. After pain relief, essential measures include ambulation with aids or physical therapy to prevent recurrence. Correcting posture is imperative, with guidance on proper weightlifting techniques. Education on lifestyle modifications, including maintaining a healthy weight and regular exercise, is essential. If conservative management fails to improve symptoms within a few weeks, other treatment options include intra-articular injections, peri-articular injections, or nerve blocks. RF treatment of the SIJ is also recommended. A current treatment option is RF ablation of the sacral dorsal rami. There are two fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous techniques for RF lesioning, the peri-foraminal and the lateral sacral crest approaches. Both techniques require the use of multiple punctures that can cause pain in the patient after the procedure [16, 17]. Dorsal innervation variability among subjects hinders the efficacy of fluoroscopy-guided RF ablation in some patients. The endoscopic-assisted SIJ denervation was described by Choi et al. in 2016 with the aim of better visualization of pain generators of the SIJ, which is difficult using the fluoroscopy-guided RF ablation technique [18]. Endoscope-guided RF ablation ensures targeted treatment of pain-causing structures. By stimulating these structures, patients can confirm the source of pain before ablation. Multiple RF ablations are possible with one approach, minimizing discomfort. Direct visualization ensures precise RF probe placement over key structures, ensuring safe ablation. When all therapeutic options fail to improve pain, surgical intervention may be considered. Arthrodesis has demonstrated efficacy in individuals experiencing severe SIJ pain unresponsive to conservative therapeutic interventions.

This case report underscores the significance of endoscopic SIJ ablation as an innovative and effective therapeutic approach in the management of recurrent refractory lower limb radiculopathy. By targeting the SIJ, a region often overlooked in the context of lumbar spine surgery, this minimally invasive procedure offers a promising avenue for mitigating recurrent symptoms and improving patient outcomes.

In instances of recurrent radiculopathy subsequent to lumbar surgery, our findings underscore the importance of considering the SIJ as a potential pain generator. Endoscopic SIJ ablation emerges as a valuable, minimally invasive intervention, offering effective relief and enhancing outcomes for patients with refractory lower limb radiculopathy. In summary, our recommendation advocates for a systematic approach integrating clinical evaluation, diagnostic blocks, and imaging studies to differentiate between lumbar spine pathology and SIJ dysfunction. This comprehensive approach facilitates the provision of tailored management plans aligning with individual patient needs, thereby optimizing outcomes.

References

- 1.Gore S, Nadkarni S. Sciatica: Detection and confirmation by new method. Int J Spine Surg 2014;8:15. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: Reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: A report of 182 operative treatments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:626-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Frymoyer JW, Hanley E, Howe J, Kuhlmann D, Matteri R. Disc excision and spine fusion in the management of lumbar disc disease. A minimum ten-year followup. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1978;3:1-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Javid MJ, Hadar EJ. Long-term follow-up review of patients who underwent laminectomy for lumbar stenosis: A prospective study. J Neurosurg 1998;89:1-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.North RB, Kidd DH, Zahurak M, James CS, Long DM. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic, intractable pain: Experience over two decades. Neurosurgery 1993;32:384-94; discussion 394-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Ross JS, Robertson JT, Frederickson RC, Petrie JL, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, et al. Association between peridural scar and recurrent radicular pain after lumbar discectomy: Magnetic resonance evaluation. ADCON-L European Study Group. Neurosurgery 1996;38:855-61; discussion 861-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Wilkinson HA. The Failed Back Syndrome: Etiology and Therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Springer New York; 1992. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Yorimitsu E, Chiba K, Toyama Y, Hirabayashi K. Long-term outcomes of standard discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: A follow-up study of more than 10 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:652-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Goldthwait JE, Osgood RB. A Consideration of the pelvic articulations from an anatomical, pathological and clinical standpoint. Boston Med Surg J 1905;152:593-601. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Cohen SP. Sacroiliac joint pain: A comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1440-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: Pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: Asymptomatic volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1475-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Ould-Slimane M, Lenoir T, Dauzac C, Rillardon L, Hoffmann E, Guigui P, et al. Influence of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion procedures on spinal and pelvic parameters of sagittal balance. Eur Spine J 2012;21:1200-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Ivanov AA, Kiapour A, Ebraheim NA, Goel V. Lumbar fusion leads to increases in angular motion and stress across sacroiliac joint: A finite element study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E162-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Unoki E, Abe E, Murai H, Kobayashi T, Abe T. Fusion of multiple segments can increase the incidence of sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:999-1005. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Lee YC, Lee R, Harman C. The incidence of new onset sacroiliac joint pain following lumbar fusion. J Spine Surg 2019;5:310-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Roberts SL, Burnham RS, Ravichandiran K, Agur AM, Loh EY. Cadaveric study of sacroiliac joint innervation: Implications for diagnostic blocks and radiofrequency ablation. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014;39:456-64. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Ho KY, Hadi MA, Pasutharnchat K, Tan KH. Cooled radiofrequency denervation for treatment of sacroiliac joint pain: Two-year results from 20 cases. J Pain Res 2013;6:505-11. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Choi WS, Kim JS, Ryu KS, Hur JW, Seong JH, Cho HJ. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation of the sacroiliac joint complex in the treatment of chronic low back pain: A preliminary study of feasibility and efficacy of a novel technique. BioMed Res Int 2016;2016:2834259. [Google Scholar | PubMed]