Minimally invasive surgical technique with navigation assistance would ensure enhanced patient safety and surgical precision in complex spine surgeries and corridors of difficult surgical access.

Dr. Guna Pratheep Kalanchiam, Clinical Fellow, Spine Surgery Unit, Department of Orthopedics, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore. E-mail: guna.hytech@gmail.com

Introduction: Surgeries in the occipitocervical and upper cervical region are always quite challenging and need adequate surgical experience and expertise. Especially in cases, where both anterior and posterior surgical access is required, complication rates could be significantly high. The transoral approach for the ventral pathologies of the upper cervical region has been previously described using the conventional open technique where post-operative morbidity is a concern. Moreover, problems such as dysphagia, risk of injury to the oral components, and surgical site infection are always an issue. In patients requiring a combined posterior approach, surgical morbidity, and post-operative recovery is always an area of concern. We describe a case report of upper cervical myelopathy managed under full navigation using a combined tubular transoral (minimally invasive) and posterior approach.

Case Report: A 74-year-old male patient presented with myelopathy and weakness in bilateral upper and lower limbs (MRC Grade 4/5) due to a cystic lesion at C1 causing ventral cord compression. A staged anterior (minimally invasive transoral tubular approach) – posterior procedure was performed under full navigation for decompression and stabilization of C1-C2. Postoperatively, the patient showed neurological improvement (MRC Grade 5/5) in all four limbs.

Conclusion: A 360° navigation-guided approach to the upper cervical spine is a safer and more effective procedure with less risk of neurological and vascular complications. Furthermore, combining minimally invasive access anteriorly to the odontoid ensures reduced surgical morbidity of the overall procedure.

Keywords: Upper cervical, circumferential, navigation, minimally invasive, transoral.

The occipitocervical and upper cervical spine pathologies are unique, owing to the complex anatomy of neural and vascular structures and they always pose a challenge to the treating surgeon. Recent advances such as navigation and robotics have revolutionized the way surgeons approach these complex surgeries. By enabling real-time visualization and feedback, a better understanding of the intraoperative anatomical relationships is possible, thereby mitigating the learning curve in spine surgeries [1]. This ensures improved safety of the surgical procedures especially in areas of difficult surgical access. The transoral approach is direct access across the occipital-cervical region and enables optimal surgical decompression of the spinal cord [2]. Most often it is used in managing ventral spinal cord pathologies like basilar invagination, tumors, and infections. Although the open transoral surgical technique has been described previously in the literature, the navigation-guided minimally invasive (MIS) transoral approach has not been reported. Our manuscript briefly elaborates on the technique of navigation-guided combined anterior (tubular transoral approach)-posterior approach, and its advantages in treating O-C and upper cervical pathologies.

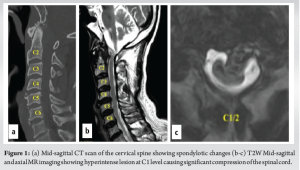

A 74-year-old male patient, a known case of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and with a history of rheumatic heart disease presented to our outpatient clinic with complaints of upper cervical pain for 1½ months, associated with unsteadiness while walking. He used to work as a bus driver but had to stop due to loss of hand dexterity, weakness, and pain. Neurological examination revealed weakness in all four limbs (motor power- 4/5 according to MRC grading). Both biceps and knee reflexes were exaggerated (3+), plantar response was extensor and he was unable to perform tandem walking. Cervical radiographs showed spondylotic changes without signs of any obvious instability and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a hyperintense lesion at the C1 level in the T2W mid-sagittal image causing significant compression and thinning of the spinal cord (Fig. 1). CT angiogram was performed and revealed a normal course of the bilateral vertebral arteries. After careful evaluation, surgical decompression of the spinal cord using a transoral approach and posterior stabilization of the upper cervical region was planned for the patient.

All procedures performed in this study were under the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees and the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this surgical technique and accompanying images.

Pre-surgical protocol

The patient was planned for a staged anterior and posterior procedure. Preoperatively, the oral cavity was thoroughly examined for dentures, tooth decay, or oral ulcers. The mouth opening was examined to check the adequacy of placing the tubular retractors as it is the surgical corridor for the transoral approach. The ability to pass three fingers into the oral cavity was considered adequate. Swabs were isolated from the buccal mucosa and posterior pharyngeal wall the day before surgery. Anti-septic aqueous mouthwash solution was used every 8 h after the swab isolation for oral hygiene.

Anesthesia and patient positioning

General anesthesia was administered with orotracheal intubation using a cuffed endotracheal tube. The patient was then positioned supine on the operating table using a Mayfield skull clamp (Integra LifeSciences Co.; USA) (Fig. 2). Neutral alignment of the cervical spine was confirmed using anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopy. Care was taken to avoid any pressure over the tongue or pressing the tongue against the teeth. To facilitate navigation, the dynamic reference array was attached to the Mayfield clamp and a continuous intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) was used in our case.

Surgical procedure

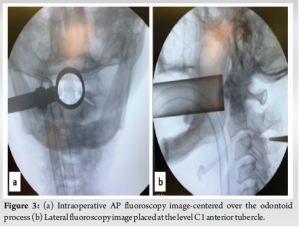

After appropriate positioning, anteroposterior (AP) and lateral fluoroscopy radiographs were performed for optimal placement of the tubes. In the AP view, trochar was placed initially and after sequential dilator (METRX Dilator) placement, a 8 cm × 26 mm tubular retractor (METRX 2; Medtronic) was docked centering the odontoid process and in the lateral view, the tube was placed at the level of the C1 anterior tubercle (Fig. 3). Intraoperative computed tomography (CT) scan was then performed using O-arm navigation (Stealth Station S8; Medtronic, Inc., USA), and high-resolution 3D reconstructed CT images of the cervical spine were obtained. All the further surgical steps were performed through the tubular retracting system using an operating microscope.

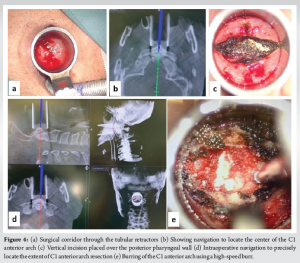

The mucosa at the incision site was infiltrated with a mixture of Lignocaine and 1:200,000 Adrenaline. A straight midline incision of about 3 cm was placed over the posterior pharyngeal wall at the level of the C1 anterior tubercle (Fig. 4). The mucosal flaps were then undermined for retractor placement and stay sutures were applied. Longus colli muscle was reflected bilaterally using monopolar electrocautery and the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) was incised to reach the C1 arch. Using the navigation, the extent of superior-inferior and mediolateral dissection was identified (Fig. 4).

Using periosteal elevators, the C1 arch was skeletonized and the bony limits of the C1 arch were confirmed using navigation. The C1 anterior arch was resected using a high-speed match head burr (60,000 rpm). Mediolaterally, the resection was performed till the outer borders of the odontoid process, and the full thickness of the C1 arch was removed. The odontoid process was visualized and the outer cortex was carefully burred (Fig. 5). After removing the cortical shell, further decancellation was performed using navigation-guided burring (Stealth-Midas System) and microcurettes. Once the inner cortex of C2 was reached, burring was discontinued. Alar and apical ligaments were detached from the odontoid peg and using bayoneted kerrison rongeur (METRX 2mm 45°) the inner cortical shell of the odontoid was removed.

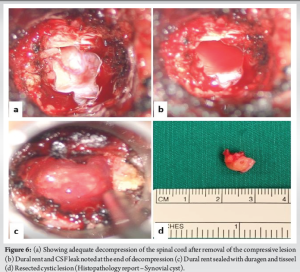

Transverse Atlantal Ligament (TAL) was noted (Fig. 5) and removed piecemeal using Kerrison rongeur. The compressive lesion was then clearly visualized and blunt dissection of the mass was performed by teasing off the adhesions from the dura. Intraoperatively, it was found that the mass was firmly adherent to the dura, and careful dissection was performed using a METRX 45° Woodson Probe (Medtronic; REF 9560640). The cystic mass was removed en bloc, resulting in an unavoidable dural defect on the anterior aspect of the dura (Fig. 6). Primary repair of the dura could not be performed and the tear was sealed with a dural substitute (Duragen XS; Integra Life Sciences Corporation, Plainsboro, New Jersey) and fibrin sealant (Tisseel, Baxter, Westlake Village, CA). After the removal of the mass, decompression was completed and the cord pulsation was visible. Throughout the procedure, no major bleeding was encountered and after achieving adequate hemostasis closure was performed in two layers (muscular and mucosal) using continuous non-absorbable sutures (3-0 vicryl).

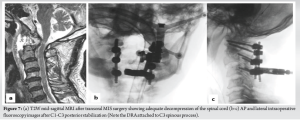

After 24 h of overnight intubation, staged posterior stabilization from C1-C3 was performed 7 days later. The patient was positioned prone on a Jackson table and the head was stabilized using a Mayfield head holder. Using a midline skin incision, C1–C3 was exposed bilaterally by exposing the C1–C2 joint and C1 lateral masses. For this, we exposed the venous plexus and cut the C2 nerve roots B/L. Bleeding from the vascular plexus was controlled using a combination of bipolar cautery, hemostatic matrix – Floseal; Baxter Healthcare Corporation Fremont, CA 94555, USA) and, gel foam. Using the navigation, it was noted that the pedicle on the right side of C2 was very narrow and precluded the placement of a pedicle screw, hence, a pars screw was preferred. A pilot hole was created with the aid of navigation, followed by insertion of the probes, taps, and screws according to the measured lengths. Finally, rods were inserted and C1–C3 stabilization was performed (Fig. 7). Bone grafts (allografts with demineralized bone matrix – Grafton DBM; Osteotech, Eatontown, New Jersey) were placed on the lateral gutters and no decompression was performed.

During both stages, there were no changes in the neuromonitoring signals. The patient was extubated and monitored in the high-dependency ward for 48 h and shifted to room air ventilation. His neurological examination showed improvement in motor strength to MRC grade 5/5 in all four limbs. Ambulation was initiated on the 2nd post-operative day under the guidance of a trained physiotherapist. The patient was maintained on a nasogastric tube for 2 weeks and then gradually advanced from liquids to soft regular foods. The biopsy report suggested the lesion as a synovial cyst. Regular follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. At our last follow-up of 3 years, clinical and radiological results were satisfactory (there was complete recovery of motor power in all four limbs, and was able to ambulate independently. Radiologically, there were no signs of C1-C2 instability and implants were in place without any evidence of screw loosening, pullout, or rod breakage).

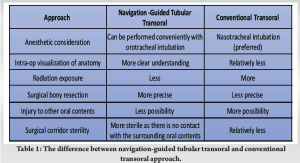

Various approaches (anterior, posterior, and lateral) have been described in the literature for the management of craniocervical pathologies [3-5]. Still, these surgeries are always complex due to the surrounding critical anatomical structures. In most instances, patients would require combined procedures for adequate decompression and optimal stabilization. Especially in ventral pathologies of the O-C and upper cervical region, an ideal decompression could be performed using an anterior approach. However, the stabilization would be biomechanically stronger using the posterior approach. Anteriorly, the transoral approach has been described initially as early as 1919, where it was performed to dislodge a bullet entrapped between the skull base and C1 [6]. Since then, it has been one of the mainstay surgical corridors in the spine surgeon’s armamentarium, especially in managing pathologies like basilar invagination, infections, and tumors in the O-C region. Techniques for the surgical stabilization of the upper cervical spine using the posterior approach have been described by various authors [7,8], however, variations in bone morphology and vertebral artery course could preclude screw placement. Our report highlights the use of tubular retractors and CT-guided intraoperative navigation in a combined anteroposterior approach in the upper cervical spine. As far as our knowledge, this is the first technical report on the use of navigation in tubular transoral combined with a posterior approach. Our technique combines the advantages of both the minimally invasive (tubular system) approach and 3D navigation. The patient had a cystic lesion at the C1 level, which is extremely rare [9,10] resulting in myelopathy. Several authors have reported surgical resection of a ventrally located C1 cyst (as in our case) using a modified posterolateral approach [9]. However, an anterior approach would be ideal for the decompression of a ventral mass. The use of a relatively safer, less invasive tubular transoral approach reduces the morbidity of the surgical procedure. The major advantage of navigation in this technique is the intraoperative understanding of the extent of bony limits and optimal dissection of bone and soft tissues. This could help avoid complications like neural and vascular injury. In our case, identifying the mediolateral and superior-inferior extent of dissection of the C1 arch was very crucial to avoid injury to the vertebral artery. Furthermore, the assessment of the thickness of the C1 arch during the burring of the bone was important to understand the depth of the surgical maneuver and prevent catastrophic spinal cord injury. Both these were evaluated precisely using the real-time navigation system. Furthermore, by conventional transoral approach, placement of the oral retractors increases the chances of injury to oropharyngeal, and perioral areas, lip lacerations, and traumatic contusion and this could be potentially minimized using the tubular retractor system [2]. As the tube system was directly placed in the oral cavity and externally mounted to a table, there was no need for mouth retractors in this technique. One other proposed advantage of tubular access was by utilizing a narrow surgical corridor, there was a reduction in the potential risk of oropharyngeal microbial contamination (Table 1).

Tubular retractors also help retract the soft palate, thereby avoiding the need for the palatal split, especially in cases that also need a clivus resection. Most of the previous studies in the literature have reported the transoral surgical procedure using nasotracheal intubation [11], as the surgical steps would be arduous to perform with an oral endotracheal tube in the surgeon’s access. In our case, we performed the surgery using the conventional orotracheal intubation. This is because the use of a tubular retractor enables the surgical steps to be performed in a minimal surgical space. Furthermore, the necessity of post-operative tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation following the transoral approach has been reported in several studies [11]. This could be mainly attributed to the edema and post-operative swelling in the oral cavity and oropharynx. However, with this minimally invasive approach, we believe that the incidence would be relatively less. Table 1 shows the differences between the conventional and the minimally invasive transoral approach. One of the most common concerns regarding spine surgical procedures is the magnitude of overall radiation exposure to the surgeons. Theocharopoulos et al. in their study showed that the radiation exposure to spine surgeons was 50 times more compared to the lifetime radiation dose of a hip surgeon [12]. Especially in complex anatomical areas like the occiptocervical region, the usage of fluoroscopy is even higher, further escalating the radiation risk to the surgeons. The use of navigation has been found to significantly reduce the occupational radiation exposure of surgeons [12,13], especially in our case, where a two-staged procedure was performed under navigation guidance. As the TAL was removed in our patient, it would result in C1-C2 instability. Hence, we performed the second stage of posterior stabilization. Screw placement in the upper cervical spine must be performed with meticulous care as the risk of screw breeches in the cervical spine is reported to be about 1.1–29% [14,15]. Using real-time navigation, the placement of screws could be performed relatively safely as it provides a precise intraoperative trajectory of the bony corridors. A meta-analysis by Tarawneh et al. [16] showed that the efficacy of navigation-guided cervical pedicle screws was significantly higher compared with fluoroscopy-guided screws, with lesser adverse events. In our case, all the screws were placed using navigation and also we were able to identify the narrow pedicle in C2, helping us to avoid cortical breach and prevent adverse events. The availability and use navigation are very important for such high cervical approaches and otherwise, it could be technically challenging in a resource-deficient setting.

This case presents the benefits of combining both minimally invasive surgical techniques with navigation assistance, thereby ensuring patient safety. Compared to the conventional techniques previously described, this navigation-guided combined technique enables direct decompression and optimal stabilization of the upper cervical region with more precision and fewer complications.

Image-guided navigation could be an invaluable tool to minimally invasive spine surgeons as it allows for a larger area of visualization of bony and soft tissues through a smaller area of surgical dissection.

References

- 1.Virk S, Qureshi S. Navigation in minimally invasive spine surgery. J Spine Surg 2019;5 Suppl 1:S25-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Araneta KT, Bundoc R. Transoral approach using a tubular retractor system in the treatment of atlantoaxial Pott’s disease: A novel method of surgical decompression. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e239240. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Rossmann T, Veldeman M, Nurminen V, Lehecka M. How I do it: Lateral approach for craniocervical junction tumors. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2023;165:1315-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Baird CJ, Conway JE, Sciubba DM, Prevedello DM, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Kassam AB. Radiographic and anatomic basis of endoscopic anterior craniocervical decompression: A comparison of endonasal, transoral, and transcervical approaches. Oper Neurosurg 2009;65:ons158. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Patel R, Solanki AM, Acharya A. Surgical outcomes of posterior occipito-cervical decompression and fusion for basilar invagination: A prospective study. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;13:127-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Kanavel K. Bullet located between the atlas and the base of the skull : Technic of removal through the mouth. Surg Clin Chicago 1917;1:361-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Du JY, Aichmair A, Kueper J, Wright T, Lebl DR. Biomechanical analysis of screw constructs for atlantoaxial fixation in cadavers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;22:151-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Goel A, Laheri V. Plate and screw fixation for atlanto-axial subluxation. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994;129:47-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Chibbaro S, Gubian A, Zaed I, Hajhouji F, Pop R, Todeschi J, et al. Cervical myelopathy caused by ventrally located atlanto-axial synovial cysts: An open quest for the safest and most effective surgical management. Case series and systematic review of the literature. Neurochirurgie 2020;66:447-54. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Okamoto K, Doita M, Yoshikawa M, Manabe M, Sha N, Yoshiya S. Synovial cyst at the C1-C2 junction in a patient with atlantoaxial subluxation. J Spinal Disord Tech 2004;17:535-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Chatain GP, Chee K, Finn M. Review of transoral odontoidectomy. Where do we stand? Technical note and a single-center experience. Interdiscip Neurosurg 2022;29:101549. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Kim CW, Lee YP, Taylor W, Oygar A, Kim WK. Use of navigation-assisted fluoroscopy to decrease radiation exposure during minimally invasive spine surgery. Spine J 2008;8:584-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Webb JE, Regev GJ, Garfin SR, Kim CW. Navigation-assisted fluoroscopy in minimally invasive direct lateral interbody fusion: A cadaveric study. SAS J 2010;4:115-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Heo Y, Lee SB, Lee BJ, Jeong SK, Rhim SC, Roh SW, et al. The learning curve of subaxial cervical pedicle screw placement: How can we avoid neurovascular complications in the initial period? Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2019;17:603-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Yoshimoto H, Sato S, Hyakumachi T, Yanagibashi Y, Kanno T, Masuda T. Clinical accuracy of cervical pedicle screw insertion using lateral fluoroscopy: A radiographic analysis of the learning curve. Eur Spine J 2009;18:1326-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Tarawneh AM, Salem KM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing the accuracy and clinical outcome of pedicle screw placement using robot-assisted technology and conventional freehand technique. Global Spine J 2021;11:575-86. [Google Scholar | PubMed]