Aberrant atypical presentation of osteomyelitis is more often than not, caused by unusual organisms especially in young immunocompetent patients, propagated by associated hypovitaminosis D and often misdiagnosed due to bizarre clinical findings.

Dr. Shreya Shenoy, Department of Orthopaedics, SKS Hospital and Postgraduate Medical Institute, Alagapuram, Salem - 636004, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: shreyasemail2@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteomyelitis in adults is most commonly associated with Staphylococcus aureus or epidermidis. Healthy bone is inherently resistant to infection, until seeding of a source of infection occurs either by hematogenous spread or by direct inoculation. Salmonella spp. has been accountable for 0.45% of all osteomyelitis regardless of the age. Due to a culmination of factors, the infection is rarely seen in an immunocompetent young adult. Here, we report a case of Salmonella osteomyelitis in a young female.

Case Report: A 24-year-old otherwise healthy female patient presented with acute-onset pain of right mid shaft of femur and proximal tibia. She had a normal radiograph with raised inflammatory parameters. She had a hypointense lesion in the T1-weighted imaging, features suggestive of osteomyelitis. A second lesion hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was seen in the proximal tibia with a fracture line in the anteromedial cortex of proximal tibia of the right leg, possibly osteomyelitis. The patient was taken up for open biopsy, sampling for culture and debridement. The culture grew Salmonella spp. The patient was treated with 6 weeks on intravenous ertapenem and 2 weeks of oral cotrimoxazole. She was completely symptom free by 6 weeks and repeat MRI at 6 months showed healed status of the index site.

Conclusion: Adult-onset acute bifocal Salmonella osteomyelitis is extremely rare. Early diagnosis and prompt debridement with tailored antibiotics help in preventing the spread of the disease and is curative.

Keywords: Salmonella osteomyelitis, adult-onset osteomyelitis, bifocal osteomyelitis, healthy individual.

Osteomyelitis in adults is most commonly associated with Staphylococcus aureus or epidermidis [1,2]. Healthy bone is inherently resistant to infection, until seeding of a source of infection occurs either by hematogenous spread or by direct inoculation [3]. The incidence of osteomyelitis has a bimodal distribution with peaks in children (<18 years) and adults above the age of 50 years [4]. The most common presentation is a focal lesion in a single bone with features of infection [5]. Recently, there has been a rise in the reports of varied presentations of adult-onset osteomyelitis adding to the challenge of diagnosis and management. Salmonella spp. has been accountable for 0.45% of all osteomyelitis regardless of the age [6]. There are over 2600 strains of Salmonella that have been identified to cause infections in humans [7]. The organism is known for its high virulence, rapid development of antibiotic resistance, and facultative anaerobic nature promoting a long latent carrier state [8]. More often associated with infections in immunocompromised individuals and children, it is rare for Salmonella spp. to be associated with osteomyelitis in a healthy adult. Here, we report a case of subacute salmonella osteomyelitis in a young immunocompetent female.

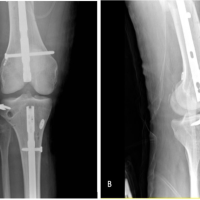

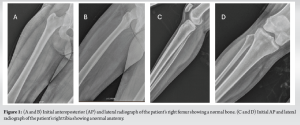

A 24-year-old female patient, with no comorbidities, presented to the Department of Orthopedics, SKS Hospital, Salem, Tamil Nadu, India, with chief complaints of severe pain of the right proximal leg and thigh for 1 week, in March 2023. She gives no history of trauma, travel, fever, or other constitutional symptoms. She gave history of diarrhea, loss of appetite with post-prandial abdominal pain 3 months ago which was left unevaluated. She had noticed one episode of blood in stool for which she presented to a local general practitioner who advised symptomatic treatment with antipyretics and iron supplements. She took treatment in alternative medicine (Siddha) for 3 months, thereafter. On clinical examination, she had severe tenderness and warmth of the mid-thigh. She had normal range of movement of the hip and a normal gait. On clinical examination of the knee, she had warmth and tenderness over the proximal tibia. A complete clinical examination of the knee showed normal range of motion at the knee. She was able to do active straight leg raising. Initial X-ray of the right leg and thigh was found to be normal (Fig. 1). As the patient had a high score on the pain scale, she was evaluated further. Laboratory investigations showed a positive C-reactive protein (CRP) value of 28.88 mg/L, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 46 mm/h, normal white blood cell count, a normal metabolic profile with a normal calcium, phosphorous, and alkaline phosphatase but low Vitamin D3 level of 16.86 ng/mL. As the inflammatory markers were raised, the patient was advised a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

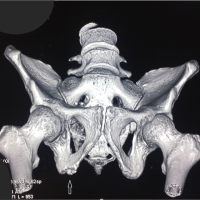

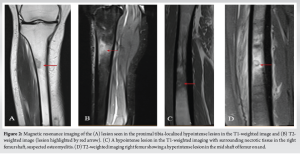

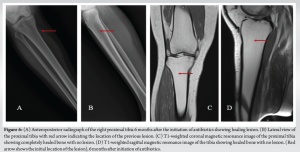

On the MRI, the patient had a hyperintense lesion in the mid shaft of the right femur with small intramedullary and subperiosteal collection on the T2-weighted imaging with hypointense lesion in the T1-weighted imaging, features suggestive of osteomyelitis. A second lesion hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted MRI was seen in the proximal tibia with a fracture line in the anteromedial cortex of proximal tibia of the right leg (unicortical), possibly osteomyelitis (Fig. 2).

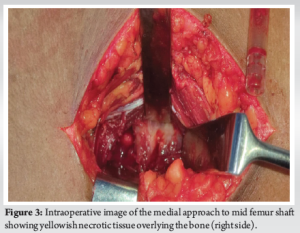

With the working diagnosis of osteomyelitis in mind, Cierny-Mader Pennick classification (9) type III A (localized osteomyelitis in a host with normal immune system) and considering the symptomatic status of the patient with persistently high CRP and ESR values, she was planned for open biopsy and debridement of the osteomyelitis. Under spinal anesthesia, aseptic precautions, the patient was positioned supine with leg in figure of four position, direct medial approach to the osteomyelitis lesion, and the lesion was exposed. The mid-shaft of femur showed periosteal reaction with necrotic tissue around the bone (Fig. 3). Thorough debridement of the periosteum and sub-periosteal tissue was done. Drill holes were made into the femoral cortex to look for intramedullary pus. No active pus was drained. Thorough wash was given and debridement done until bleeding bone and healthy tissues were seen. Antibiotic impregnated beads (vancomycin and gentamycin) (Stimulan® Rapid Cure, Biocomposites, UK) were placed in the bone. Adequate hemostasis was achieved. Wound was closed in layers.

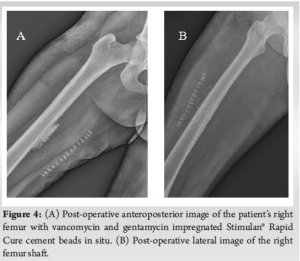

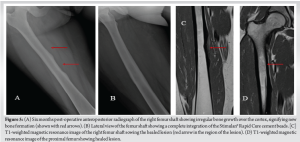

The tissue samples were sent for histopathological examination, culture and sensitivity, and X-PERT analysis for tuberculosis. The culture grew Salmonella spp. Sensitivity pattern showed the organism to be resistant to amikacin, ciprofloxacin, gentamycin, levofloxacin, and cefaperazone-sulbactam. It was sensitive to ofloxacin, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin- clavulanic acid, and ertapenem. The X-PERT analysis was negative for tuberculous bacilli. Species identification of the bacillus could not be done. The histopathological examination showed acute inflammatory exudate with necrotic tissue, consistent with features of osteomyelitis of femur. Postoperatively, we ruled out sickle cell disease by a peripheral smear. She was started on intravenous ertapenem based on the MIC level and continued for 6 weeks, followed by 2 weeks of oral cotrimoxazole. Only partial weight-bearing with support was allowed till 6 weeks postoperatively, full-weight-bearing thereafter. She presented for follow-up on day 7, 14, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. Serial CRP level monitoring was done. Follow-up radiograph showed healing of the cortex and integration of the antibiotic beads (Fig. 4 and 5). Repeat MRI was done at 6-month mark postoperatively which showed healed lesions at both mid shaft of femur and proximal tibia (Fig. 6). The patient is currently asymptomatic and doing all activities of daily living.

Salmonella is a rod shaped Gram negative, non-spore forming bacillus of the Enterobacteriaceae family, usually associated with systemic diseases in adults [9]. Clinical spectrum of Salmonella infections range from enteric fever or typhoid to sepsis [10]. Only 0.8% of all Salmonella infection results in osteomyelitis, seen more frequently in immunocompromised children, usually associated with thalassemia trait or sickle cell disease [10-12]. However, the reports on incidence of Salmonella osteomyelitis in otherwise healthy adults have been on the rise world over [2]. Huang et al. [2], in their systematic review, discuss around 70 case reports of Salmonella osteomyelitis in healthy individuals till 2021. They report a middle age male preponderance with most common reported sites to be femur, tibia, and the vertebra. Salmonella is generally acquired though food or drinking water from a carrier [10]. The spread of the organism is usually hematogenous and seeding [11]. Multiple predisposing factors such as travel, diabetes mellitus, sickle cell anemia, immunocompromised status, chronic steroid abuse, and exposure to reptiles have been identified [13,14]. There have also been reports of hypovitaminosis D precipitating osteomyelitis in healthy individuals [15,16]. Our patient had low Vitamin D levels which could have helped in early disease progression. Salmonella osteomyelitis has been more often reported in diaphysis of long bones such as femur, humerus, and rarely in the metaphyseal region [2,9,17,18]. It is unusual for osteomyelitis to occur in more than one bone [5]. Our patient had simultaneous lesion in the ipsilateral femur and proximal tibia, making this is a rare occurrence. Often mistaken for tumors, the actual diagnosis of osteomyelitis or a Brodie’s abscess is missed [7]. Similar to children, the adult “typhoid” osteomyelitis usually begins as a osteitis, well localized lesion with delayed onset of clinical symptoms [19]. With the progression of time, the infection becomes chronic (>3 months duration). The investigation of choice for the early diagnosis of these lesion would be the MRI. MRI is more sensitive to the early changes in osteomyelitis, well before clinical disease sets in [6]. Management of the osteomyelitis is multimodal. Tailored antibiotics as per the resistance profile of the organism and the patient’s response along with surgical debridement is the treatment of choice. Previously, the Cierny regime of staged debridement and bone grafting was followed for all cases [20,21]. However, studies report that with advancing antibiotics and earlier diagnosis of the disease, we can eliminate the need for a secondary procedure in all patients and shift to a patient specific approach to the management of osteomyelitis, especially in the case of acute onset osteomyelitis [22,23]. Of the two lesions in our patient, we did open debridement of the mid-femur shaft lesion. The proximal tibia lesion was not addressed due to the smaller diameter on the MRI. We did not anticipate Salmonella osteomyelitis preoperatively. Multiple treatment options are described in literature, notably in the Indian context; there have been reports of use of antibiotic impregnated K-nails showing promising results in osteomyelitis [24]. The use of antibiotic filled cement beads are an excellent method to address the dead space left behind by the necrotic bone and the residual organism [25]. Unfortunately, 85% of the Salmonella strains are found to be multi drug resistant [8]. The propensity of the bacterium to develop drug resistance, high virulence, and property to form biofilms makes the eradication of the organism difficult. In our case, the bacillus was found to be resistant to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and to beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combination. But the availability of other antibiotics with a good MIC helped our case. Furthermore, the evidence regarding the use of intravenous and oral antibiotic postoperatively is deficient. We advised a total antibiotic duration of 2 months with 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotic-ertapenem and 2 weeks of oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim [14,26]. This ensured good bone penetration and targeted the lesion in the proximal tibia which was not debrided. With a combination of surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy, the prognosis of Salmonella osteomyelitis has been found to be good, with a cure rate of 77.7% [4].

Adult-onset acute bifocal Salmonella osteomyelitis is extremely rare. Early diagnosis and prompt debridement with tailored antibiotics help in preventing the spread of the disease and is curative.

When a young immunocompetent otherwise healthy patient presents with features of osteomyelitis, it is extremely important to isolate the organism of concern and administer the right treatment, a combination of surgical debridement and antibiotics as per culture sensitivity for optimal results. A high index of suspicion would help the surgeon, and the microbiologist work together to identify organisms like Salmonella even in unusual presentations.

References

- 1.Ingram R, Redding P. Salmonella virchow osteomyelitis. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:440-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Huang ZD, Wang CX, Shi TB, Wu BJ, Chen Y, Li WB, et al. Salmonella osteomyelitis in adults: A systematic review. Orthop Surg 2021;13:1135-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Waldvogel FA. Acute osteomyelitis. In: Schlossberg D, editor. Orthopedic Infection. Clinical Topics in Infectious Disease. New York: Springer; 1988. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Kremers HM, Nwojo ME, Ransom JE, Wood-Wentz CM, Melton LJ 3rd, Huddleston PM 3rd. Trends in the epidemiology of osteomyelitis: A population-based study, 1969 to 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:837-45. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Sipahioglu S, Askar H, Zehir S. Bilateral acute tibial osteomyelitis in a patient without an underlying disease: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2014;8:388. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Rentmeister V, Lorenzo-Villalba N, Gorur Y, Yerna M, Ali D. Salmonella osteomyelitis of unknown origin: An underestimated infection. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 2023;10:004092. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Charosky CB, Marcove RC. Salmonella Paratyphi osteomyelitis. Report of a case simulating a giant cell tumor. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1974;99:190-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Mina SA, Hasan MZ, Hossain AK, Barua A, Mirjada MR, Chowdhury AM. The prevalence of multi-drug resistant Salmonella typhi isolated from blood sample. Microbiol Insights 2023;16:11786361221150760. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Salem KH. Salmonella osteomyelitis: A rare differential diagnosis in osteolytic lesions around the knee. J Infect Public Health 2014;7:66-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Declercq J, Verhaegen J, Verbist L, Lammens J, Stuyck J, Fabry G. Salmonella typhi osteomyelitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1994;113:232-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Carroll DS, Hughes JG. Salmonella osteomyelitis complicating sickle cell disease. Pediatrics 1957;19:184-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Atkins BL, Price EH, Tillyer L, Novelli V, Evans J. Salmonella osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease children in the East end of London. J Infect 1997;34:133-8.Atkins BL, Price EH, Tillyer L, Novelli V, Evans J. Salmonella osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease children in [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Willen J, Mayer J, Habeck C, Weiner S. Chronic Salmonella Osteomyelitis in a Healthy, Immunocompetent Man: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2021 Dec 22;11(4). doi: 10.2106/JBJS.CC.21.00356. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 14.McAnearney S, McCall D. Salmonella osteomyelitis. Ulster Med J 2015;84:171-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Chen X, Zhang Q, Song T, Zhang W, Yang Y, Duan N, et al. Vitamin D deficiency triggers intrinsic apoptosis by impairing SPP1-dependent antiapoptotic signaling in chronic hematogenous osteomyelitis. Gene 2023;870:147388. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Zargaran A, Zargaran D, Trompeter AJ. The role of vitamin D in orthopaedic infection: A systematic literature review. Bone Jt Open 2021;2:721-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Hashimoto K, Nishimura S, Iemura S, Akagi M. Salmonella osteomyelitis of the distal tibia in a healthy woman. Acta Med Okayama 2018;72:601-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Kim BK, Dan J, Lee YS, Kim SH, Cha YS. Salmonella osteomyelitis of the femoral diaphysis in a healthy individual. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2014;43:E237-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Veal JR. Typhoid and paratyphoid osteomyelitis. Am J Surg 1939;43:594-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Cierny G, Mader JT. Adult chronic osteomyelitis. Orthopedics 1984;7:1557-64. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Arora A, Singh S, Aggarwal A, Aggarwal PK. Salmonella osteomyelitis in an otherwise healthy adult male-successful management with conservative treatment: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2003;11:217-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Lari A, Esmaeil A, Marples M, Watts A, Pincher B, Sharma H. Single versus two-stage management of long-bone chronic osteomyelitis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2024;19:351. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.McNally MA, Ferguson JY, Lau AC, Diefenbeck M, Scarborough M, Ramsden AJ, et al. Single-stage treatment of chronic osteomyelitis with a new absorbable, gentamicin-loaded, calcium sulphate/hydroxyapatite biocomposite: A prospective series of 100 cases. Bone Joint J 2016;98-B:1289-96. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Jain M, Parija D, Nayak M, Ajay SC. Garre’s sclerosing chronic osteomyelitis of femur in an adolescent. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:15-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Bor N, Dujovny E, Rinat B, Rozen N, Rubin G. Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis with antibiotic-impregnated polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) - the Cierny approach: Is the second stage necessary? BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:38. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Santos EM, Sapico FL. Vertebral osteomyelitis due to salmonellae: Report of two cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:287-95. [Google Scholar | PubMed]