The article discusses the challenges of treating aggressive giant cell tumors of the proximal femur through personalized strategies involving curettage, fixation, and cement, emphasizing the need for precise surgical techniques and long-term follow-up to prevent recurrence and preserve joint function.

Dr. Abhishek Singh, I Block, Room no-204, MMU Campus, Mullana - 133207, Ambala, Haryana, India. E-mail: avi2391994@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a locally aggressive, benign neoplasm, accounting for approximately 20% of all bone tumors. While the distal femur and proximal tibia are the most common locations for GCTs, with the majority arising in the epiphyseal regions, their occurrence in the proximal femur is relatively rare, representing only 5.5% of cases. These tumors pose significant management challenges due to their tendency to cause pathological fractures, aggressive local behavior, and involvement of critical weight-bearing bones. Effective treatment requires careful consideration of both oncological control and functional preservation.

Case Report: A 43-year-old male presented with a GCT in the proximal femur, complicated by a pathological fracture of the femoral neck. Given the tumor’s size and location, the patient underwent extended curettage (EC) to remove the tumor, followed by internal fixation with a dynamic hip screw and the application of bone cement for additional stabilization. Post-operative monitoring, including clinical and radiological assessments, showed favorable results. After a 12-month follow-up period, the patient had no signs of recurrence, and his functional and radiological outcomes were excellent, with restored mobility and the ability to bear weight on the affected limb.

Conclusion: This case emphasizes the need for a tailored treatment strategy when managing GCTs of the proximal femur, particularly in resource-limited settings. The combination of EC, internal fixation, and bone cement was effective in achieving both oncological control and functional recovery. Long-term follow-up remains essential to monitor for recurrence and to ensure the integrity of the fixation device. The positive outcomes in this case highlight the potential for successful management of GCTs in challenging anatomical locations with appropriate surgical intervention and post-operative care.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, proximal femur, pathological fracture, dynamic hip screw.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a common primary bone tumor that exhibits erratic biological behavior, significant bone erosion, and a high recurrence rate [1]. According to studies, GCT accounts for approximately 20% of all benign bone tumors, with malignant transformation occurring in approximately 10% and lung metastasis occurring in 1–4% of patients. The age of onset is primarily between 20 and 40 years old, with women being more common [2]. It is also classified as a locally destructive intermediate bone tumor due to its extensive bone and soft-tissue invasion. The most prevalent sites are the epiphyseal areas of the distal femur and proximal tibia, which account for approximately 60–70% of GCT in all body parts [3]. The incidence of GCT in the proximal femur is relatively low, accounting for about 5.5% of GCT. Nonetheless, it has the characteristics of a high recurrence rate and poor prognosis [4]. The lesions are primarily located in the femoral neck and intertrochanteric region, which are crucial areas for the mechanical function of the human body. As these regions play a key role in weight-bearing and movement, the likelihood of pathological fractures is higher compared to GCT around the knee joint. Although it is less common for these tumors to extend into the joint cavity, they can infiltrate the subchondral bone, which can significantly impair the function of the hip joint [5]. The treatment of proximal femoral GCT is more challenging. At present, there are few literature reports on proximal femoral GCT, and there is no unified treatment principle [6]. The choice of surgical methods is also controversial, which mainly includes extended curettage (EC) and bone cement filling, segmental resection, and tumor hip prosthesis reconstruction [7]. The aim of treatment of proximal femoral GCT at this stage is primarily to completely remove the lesions, reduce the recurrence rate, restore the flatness of the joint surface, and prevent complications. These will help restore the normal biological function of the hip joint to the greatest extent and achieve a satisfactory survival prognosis.

A 43-year-old male presented with the chief complaints of pain and inability to bear weight over his right lower limb. He had a history of falling from stairs 3 months ago, after which he developed pain in his right hip but was still able to perform all activities. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done outside at the time of injury suggested the presence of an expansile lytic lesion measuring approximately 5.6 × 4.1 cm in the meta-diaphyseal region of the proximal femur, primarily involving the greater trochanter, with no evidence of a pathological fracture (Fig. 1).

One day prior to the presentation, the patient experienced sudden pain in his right hip while performing hip movements. Upon evaluation, the patient’s right lower limb was found to be in extension, abduction, and external rotation. Radiological examination revealed a fracture of the femoral neck along with a lytic lesion in the proximal femur (Greater trochanter region) on the right side (Fig. 2). An MRI of the pelvis with both hip joints was performed to assess the extent of the lesion. The results indicated an expansile, lobulated soft tissue mass involving the greater trochanter of the right femur, extending into the femoral neck. This was associated with cortical thinning and a pathological fracture of the femoral neck, suggesting a possible GCT (Fig. 3).

The patient underwent EC followed by open reduction and internal fixation using a dynamic hip screw (DHS), with simplex bone cement through the lateral approach.

Surgical procedure

The patient was placed in a supine position on a fracture table. Fracture reduction was achieved through manual traction and digital manipulation, with confirmation under fluoroscopy. A curvilinear skin incision, approximately 10 cm in length, was made distal to the greater trochanter. Superficial dissection was performed, the iliotibial band was incised along the incision line, and the vastus lateralis was split and retracted anteriorly. The proximal femur was exposed, and the lateral cortex over the proximal femur was opened. Intralesional curettage of the tumor was done utilizing fluoroscopy. The cavity was packed with hydrogen peroxide soaked gauge. An intraoperative biopsy sample was collected for histopathological examination. A DHS angle guide (135°) was used, and a guidewire was inserted through it up to the subchondral location in the femoral head, confirmed under fluoroscopy in both anteroposterior and lateral views. Triple reaming was performed along the same path. An 80 mm Richard screw was inserted, followed by the introduction of the DHS plate with cortical screws. Bone cement was then injected into the scooped area of the proximal femur (Fig. 4). The remaining screws were inserted, and the fracture reduction, along with the position of the plate and screws, was confirmed under fluoroscopy (Fig. 5).

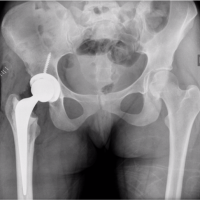

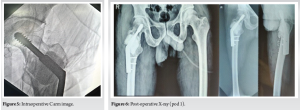

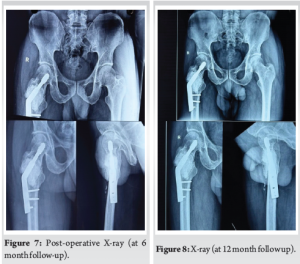

Postoperatively, X-rays were taken (Fig. 6), and no complications were seen. The patient was advised non-weight-bearing mobilization for 6 weeks, and then weight-bearing was started gradually.

Follow-up and evaluation

The first re-examination was started in the 1st month after surgery, and follow-ups were conducted at 2 months, 4 months, 6 months (Fig. 7), and 12 months (Fig. 8). The follow-up examinations included local X-rays, surgical site inspection, and range of motion.

GCT of bone is characterized by its locally aggressive nature, potential for recurrence, and rare but serious complications like malignant transformation and metastasis[8]. Unlike GCTs around the knee, proximal femoral lesions pose unique challenges due to their mechanical significance in weight-bearing and mobility. Lesions in this location often lead to structural instability, cortical thinning, and increased susceptibility to pathological fractures [9]. The tumor’s biological behavior varies significantly depending on its location, with proximal femoral GCTs being associated with higher recurrence rates and poorer prognosis compared to those in the distal femur or proximal tibia. This is attributed to the difficulty in achieving complete tumor excision while preserving joint function in this critical area [10]. Infiltration into the subchondral bone and surrounding soft tissues further complicates surgical intervention. The treatment of GCT aims to achieve local tumor control, minimize recurrence, and restore joint functionality. The choice of procedure depends on the extent of the tumor, the presence of pathological fractures, and available resources [11]. Common approaches include EC with bone cement; curettage remains the preferred method for most GCTs, especially in cases where joint preservation is desired. Bone cement is frequently used to fill the tumor cavity, providing mechanical stability and allowing immediate post-operative weight-bearing [12]. In addition, cement can facilitate early detection of recurrence on imaging. However, studies report recurrence rates of 25–50% after curettage, necessitating meticulous removal of tumor tissue and possible adjuvant therapies such as cryotherapy, phenol application, or argon beam coagulation [13]. Pathological fractures in proximal femoral GCTs require additional stabilization beyond simple curettage and cementation. The use of a DHS provided fracture fixation and load-sharing capacity, enabling gradual mobilization and early functional recovery. This approach is particularly suitable for patients with financial constraints or in settings where prosthetic replacement is not feasible [14]. For campanacci stage III GCTs or recurrent cases, wide excision followed by endoprosthetic replacement offers better local control and lower recurrence rates. However, it is associated with significant morbidity, loss of native joint function, and high financial costs, making it less desirable for select patients [9]. Silva et al. (2016) presented a case report on a rare occurrence of GCT in the femoral neck, highlighting the complexities in diagnosis and treatment. The case involved a 36-year-old female who experienced progressive hip pain and difficulty walking. Imaging studies revealed an osteolytic lesion in the femoral neck with cortical thinning, raising concerns about a potential pathological fracture [15]. To address these challenges, the authors opted for an EC followed by bone grafting and internal fixation with a DHS. This treatment strategy was chosen to: Preserve the native hip joint and avoid the significant morbidity associated with endoprosthetic replacement, provide immediate structural stability through internal fixation, minimize recurrence risk through meticulous curettage and the use of adjuvant therapies. This technique has also been supported by studies such as et al. (2014), which showed superior functional outcomes and reduced complication rates when internal fixation was used in conjunction with curettage [16]. The treatment choice in this case resulted in satisfactory oncological and functional outcomes over a 12-month follow-up period. The patient demonstrated stable implant fixation, no evidence of recurrence, and progressive weight-bearing without complications such as cement breakage or implant failure. These results are consistent with reports in the literature suggesting that the combination of curettage, cementation, and internal fixation can provide durable outcomes for select patients.

GCT of the proximal femur, particularly with associated pathological fractures, represents a significant clinical challenge due to the tumor’s aggressive nature and the mechanical demands of the hip joint. This case demonstrates that EC combined with DHS fixation and bone cement can provide satisfactory oncological and functional outcomes, particularly in resource-limited environments. While wide excision and prosthetic reconstruction remain the gold standard for advanced cases, this approach offers a cost-effective alternative for select patients. Long-term follow-up is essential to monitor for recurrence, assess the durability of the implant and cement, and ensure sustained functional recovery.

The clinical takeaway from this article is that managing GCTs of the proximal femur requires a personalized approach due to the tumor’s aggressive nature and its involvement in a critical weight-bearing area. A combination of EC, DHS fixation, and bone cement provides an effective treatment option, particularly in resource-constrained settings, addressing both tumor excision and fracture stabilization. Careful surgical technique, use of fluoroscopic guidance, and thorough long-term follow-up are essential for achieving positive oncological and functional outcomes. Continuous monitoring is necessary to detect recurrence, ensure implant stability, and support long-term recovery, given the higher recurrence rates and poorer prognosis in proximal femoral GCTs.

References

- 1.Klenke FM, Wenger DE, Inwards CY, Rose PS, Sim FH. Recurrent giant cell tumor of long bones: Analysis of Surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;469:1181-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Niu X, Zhang Q, Hao L, Ding Y, Li Y, Xu H, et al. Giant cell tumor of the extremity: Retrospective analysis of 621 Chinese patients from one institution. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:461-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.He H, Zeng H, Luo W, Liu Y, Zhang C, Liu Q. Surgical treatment options for giant cell tumors of bone around the knee joint: Extended curettage or segmental resection? Front Oncol 2019;9:946. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Shi J, Zhao Z, Yan T, Guo W, Yang R, Tang X, et al. Surgical treatment of benign osteolytic lesions in the femoral head and neck: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:549. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Wijsbek AE, Vazquez-Garcia BL, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Abudu AA, Tillman RM, et al. Giant cell tumour of the proximal femur: Is joint-sparing management ever successful? Bone Joint J 2014;96-B:127-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Montgomery C, Couch C, Emory CL, Nicholas R. Giant cell tumor of bone: Review of current literature, evaluation, and treatment options. J Knee Surg 2018;32:331-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Dabak N, Gocer H, Cirakli A. Advantages of pressurized-spray cryosurgery in giant cell tumors of the bone. Balkan Med J 2016;33:496-503. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Gulia A, Puri A, Prajapati A, Kurisunkal V. Outcomes of short segment distal radius resections and wrist fusion with iliac crest bone grafting for giant cell tumor. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019;10:1033-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:106-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Balke M, Schremper L, Gebert C, Ahrens H, Streitbuerger A, Koehler G, et al. Giant cell tumor of bone: Treatment and outcome of 214 cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2008;134:969-78. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Persson BM, Ekelund L, Lovdahl R, Gunterberg B. Favourable results of acrylic cementation for giant cell tumors. Acta Orthop Scand 1984;55:209-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Von Steyern FV, Kristiansson I, Jonsson K, Mannfolk P, Heinegard D, Rydholm A. Giant-cell tumour of the knee: The condition of the cartilage after treatment by curettage and cementing. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:361-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Errani C, Tsukamoto S, Leone G, Righi A, Akahane M, Tanaka Y. Giant cell tumor of bone: current treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010 Jul;22(4):412–9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Schwab JH, Tadros A, Athanasian EA, Morris CD, Boland PJ, Healey JH. Management of large skeletal defects following curettage of giant cell tumor of bone. Skeletal Radiol 2009;38:421-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Silva P, Amaral RA, Oliveira LA, Moraes FB, Chaibe ED. Giant cell tumor of the femoral neck: Case report. Rev Bras Ortop 2016;51:739-43. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.van der Heijden L, Dijkstra PD, van de Sande MA, Kroep JR, Nout RA, van Rijswijk CS, et al. The clinical approach toward giant cell tumor of bone. Oncologist. 2014;19(5):550–61. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0432. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]