3D printing as a valuable tool in pre-operative planning.

Dr. Suraj Prakash , Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, M S Ramaiah Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: suraj.prakash2210@gmail.com

Introduction: A neglected Monteggia fracture refers to a proximal ulna fracture accompanied by a dislocated radial head that remains untreated for a duration exceeding 4 weeks following the initial injury. We present the case of a complex neglected Monteggia fracture and its unique pre-operative approach for radial head osteotomy using 3D-printed models.

Case Report: An 8-year-old girl presented with a delayed diagnosis of a Monteggia fracture, which had become increasingly complex due to late intervention and prior inadequate management. We discuss the clinical presentation, radiological features, differential diagnosis, treatment options, and long-term outcomes using a unique pre-operative approach.

Conclusion: 3D printing has been used around the world in orthopaedics for a myriad of fractures but we present the novel technique used in this case of a neglected Monteggia fracture which gave us access to tactile feedback of the radial head deformity with its relation to the ulnar and the capitellum which served as a blueprint in planning the osteotomy/reconstruction procedure thus improving our accuracy, efficiency intraoperatively and better overall patient outcome post-operatively.

Keywords: Neglected, monteggia, osteotomy, 3D, tactile.

A Monteggia fracture involves a break in the proximal ulna accompanied by displacement of the radial head from its normal position. Neglected Monteggia fractures are defined as fractures with presentation of more than 4 weeks [1]. Chronic untreated Monteggia fractures lead to severe complications such as ulnar displacement, malunion, and disruption, leading to angulation or shortening [2]. Bado had classified the Monteggia lesion into 4 types with respect to the angulation of the radial head, with type IV being the most common type [3]. In pediatric cases, prolonged dislocation of the radial head often results in hypertrophy of both the radial head and the proximal portion of the radius. The radial head is stimulated post-traumatically, probably due to traction on the periosteum or the interosseous membrane [4]. Various modalities of treatment, such as closed or open reduction, trans-articular, fixation, osteotomy of the ulna or radius, annular ligament reconstruction, or a combination of these procedures. In this case, we report a young girl with a Bado type IV Monteggia lesion presented to us 1 year after her injury.

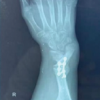

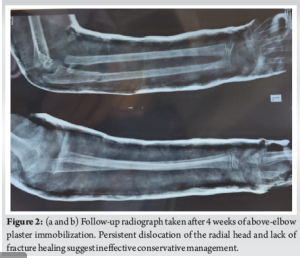

A young girl had a history of trauma to the left elbow during a school activity. The parents give a history of a fall on an outstretched hand planted firmly on the ground, suggestive of varus stress on the left elbow. There were no external wounds or distal neurovascular deficit in the upper limb. She had complaints of sudden onset pain, swelling, and restriction of movements in the left elbow. She was taken to a local hospital wherein radiographs were taken (Fig. 1) and was managed conservatively with above elbow plaster of paris application for 4 weeks (Fig. 2). She presented to our out patient department almost 1 year post the injury with complaints of pain on rest and pain at terminal flexion and extension with restriction of movements of her left elbow.

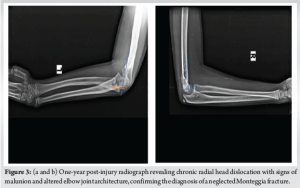

On examination, the patient had complete flexion and extension of the left elbow which was compared to the opposite side. Pain on terminal flexion and extension was noted. The patient had a reduction of pronation and supination of the left elbow compared to the opposite side. The wrist joint was duly examined and was found to be normal. Radiographs were taken of both elbow joints, and the patient was diagnosed to have a neglected left Monteggia fracture (Bado type IV) with a malunited radial head (Fig. 3).

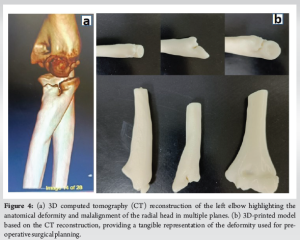

A computed tomography (CT) of the left elbow was ordered with due stress on 3D reconstruction to visualise the deformity from different planes. The parents were counselled regarding the need for surgery to correct the deformity and to restore the appropriate radial head alignment. Using the CT 3D reconstruction video (Fig. 4a), a plan was formulated to form a 3D model of the malunited radial head with its articulation at the radio-ulnar and radio-humeral joint. The 3D reconstruction models were brought to life (Fig. 4b), and with it, our osteotomy methodology was envisioned.

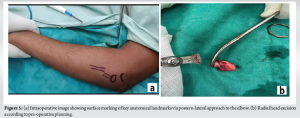

With the help of the 3D model, the corrective osteotomy of the radial head was planned and performed, which helped in understanding the most suitable radial head alignment for the best possible surgical outcome. Hence, the surgical team was able to anticipate the intra-operative obstacles that may arise while diving into an osteotomy planned on a 2D platform but executed on a 3D structure. Pre-operative workup was done, and the patient was taken up for surgery. She was placed in a supine position with her forearm resting on a hand table. Surface marking of the anatomical landmarks was done. Postero-lateral approach to the radial head was taken (Fig. 5a). The plane between the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris was identified. The capsule of the elbow joint was incised to expose the malunited radial head, capitellum, and annular ligament.

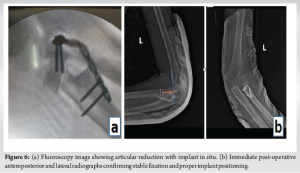

The radial head osteotomy with resurfacing was done (Fig. 5b) as planned pre-emptively on our 3D model, and fixation and alignment were done and held in place using AO 5-holed radial head ring plate (Fig. 6a). Fluoroscopy was used to confirm appropriate articular reduction and position of implants in situ. Intraoperatively, full range of motion was executed passively on the table. The elbow joint appeared to be stable throughout its range of motion. The wound was closed in layers, and sterile dressing was done. Post-operative X-rays were taken (Fig. 6b and c). The patient was placed in an arm pouch. Dressing was done once every 3 days.

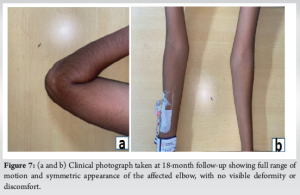

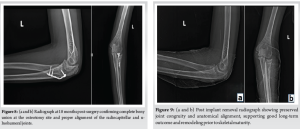

The patient was reviewed 1 year 6 months after surgery and presented with full, painless range of motion of the left elbow compared to the opposite side (Fig. 7). Radiographs taken showing union of radial head at the time of follow up (Fig. 8). The patient also underwent implant removal before skeletal maturity to allow the natural course of remodelling and preventing limb length discrepancy (Fig. 9).

Monteggia fractures are fractures most commonly seen in the paediatric age group. They are often misdiagnosed as the ulnar component typically receives more clinical attention than the associated radial head dislocation. Bado type 4 fractures are when anterior dislocation with a fracture of the radius (1%). This type occurs chiefly in adults and is exceedingly rare in pediatric patients [4]. There is documented evidence of long-term consequences of missing the diagnosis. Delpont et al. states that in children, chronic radial head dislocation results in hypertrophy, not only of the radial head, but also of the overall proximal radius [4]. Such post-traumatic growth is likely influenced by persistent traction forces on soft-tissue structures such as the periosteum or interosseous membrane [5]. The radial head plays a key role in lateral elbow stability, and chronic misalignment may contribute to valgus deformity and subsequent ulnar nerve stress. These may lead to decreased range of motion associated with elbow affliction, neurologic deficits, and valgus deformity [6]. The axis of rotation proximally passes through the center of the radial head and distally through the fovea of the ulna [7]. Osteotomies for neglected radial head dislocations have been well documented. Futami et al. described a rotation osteotomy of the radius based on the principle of functional anatomy, according to which the radial head attains its largest stability when the forearm is externally rotated. It reduces the tension of the biceps muscle, which is considered the main factor responsible for recurrent anterior dislocation, and increases the tension of the pronator teres and pronator quadratus muscle [8]. Typically, the long axis of the radius is angled slightly near the radial tuberosity. During forearm pronation, the radial head is oriented forward, while in forearm supination, it faces backward. Therefore, a transverse osteotomy of the radial shaft with supination of the proximal fragment can help correct an anterior dislocation of the radial head [9]. Freedman et al. reported reduction of a neglected radial head through radial shortening and deeping of the radial notch without repair on the annular ligament [10]. The treatment for chronic Monteggia fractures was a proximal opening-wedge osteotomy of the ulna (Bouyala technique). The Bouyala technique was described as ulnar flexion osteotomy associated with annular ligament repair. The so-called golden standard treatment of the Monteggia dislocation is the open reduction and internal fixation of the ulna fracture accompanied by closed reduction of the radial head [11]. According to Nakamura et al. favorable outcomes can be expected in the long term in delayed cases, when the patient presents before 12 years of age and within 3 years after the trauma. Monteggia fractures with Bado type IV, chiefly seen in adults and exceedingly rare in pediatric age group (1%) have shown to have poor outcomes post-surgery [4]. The most frequent complications are peri-implant infections, implant failure, loss of reduction, stiffness or instability, however none of these complications were tackled in our case. The excellent outcome of the patient suggests that 3D printing with the present technology can be used as an integral tool to treat malunited fractures and radial head dislocations. This case emphasizes the value of using 3D-printed models in pre-operative planning for radial head osteotomy which helped us understand the altered anatomy of the malunited radial head. The model facilitated accurate realignment of the radial head, restoring joint congruity at both the radiocapitellar and ulnohumeral interfaces. Thus, 3D-printed models can aid the surgeon in pre-operative planning in complex cases. This helps in anticipating our approach, obstacles and reduces the intra-operative time and soft tissue handling thus aiding in faster recovery.

A case of neglected Monteggia is being reported. Its presentation involving the malunion of the radial head is rare and unconventional, underscoring the need for awareness and consideration of this condition. Monteggia fractures require early early diagnosis and prompt management. If neglected and treatment is delayed, it could progress to cubitus varus/valgus deformity leading to chronic elbow instability and neurological deficit causing functional impairment at an early age. Early diagnosis and timely intervention of this condition are necessary to preserve joint function and prevent deformity. By implementing newer techniques, this article explores ability to bridge the gap between technology and conventional surgery and aids clinicians in better pre-operative planning through bone models supplementing with tactile information in order to achieve accurate intraoperative results. This provides effective care, accuracy and can prevent post-operative complications.

This case highlights the critical role of 3D printing in the pre-operative planning of complex orthopedic surgeries, particularly in managing neglected Monteggia fractures. Utilizing 3D-printed models enhances understanding of the anatomical deformities, allows for precise surgical planning, and improves intraoperative accuracy. Early recognition and intervention in neglected fractures are essential to prevent long-term complications. Incorporating advanced technologies like 3D printing can significantly aid clinicians in achieving better patient outcomes, ultimately enhancing surgical precision, reducing recovery time and providing good prognosis to the patient.

References

- 1.Khatri K, Rajpal K, Singh J. Bilateral monteggia fracture: A rare case presentation. J Orthop Case Rep 2020;10:76-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Dandi S, Mishra NR, Rana R, Behera HB. Old monteggia fracture-dislocation treated with plating and forearm fascial slip annular ligament reconstruction: A rare method of treatment and review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2023;13:92-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Bado JL. The monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1967;50:71-86. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Delpont M, Louahem D, Cottalorda J. Monteggia injuries. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018;104:S113-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Loubignac F, Giugliano V, Bertrand JG. A rare case of monteggia’s lesion in children. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2001;11:243-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Olney BW, Menelaus MB. Monteggia and equivalent lesions in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:219-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Fischer KJ, Manson TT, Pfaeffle HJ, Tomaino MM, Woo SL. A method for measuring joint kinematics designed for accurate registration of kinematic data to models constructed from CT data. J Biomech 2001;34:377-83. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Futami T, Tsukamoto Y, Fujita T. Rotation osteotomy for dislocation of the radial head. 6 cases followed for 7 (3-10) years. Acta Orthop Scand 1992;63:455-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Tajima T, Yoshizu T. Treatment of long-standing dislocation of the radial head in neglected monteggia fractures. J Hand Surg Am 1995;20:S91-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Freedman L, Luk K, Leong JC. Radial head reduction after a missed monteggia fracture: Brief report. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70-B:846-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Josten C, Freitag S. Monteggia and monteggia-like-lesions: Classification, indication, and techniques in operative treatment. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2009;35:296-304. [Google Scholar | PubMed]