Harvesting the peroneus longus tendon for ACL reconstruction results in only mild and transient donor site complications, making it a safe and functionally effective alternative autograft with minimal long-term ankle morbidity.

Dr. Tribhuwan Narayan Singh Gaur, Department of Orthopaedics, Government Medical College, Datia, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: tribhuwan_dr@rediffmail.com

Introduction: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common and debilitating, often requiring surgical reconstruction. The peroneus longus tendon (PLT) is a promising autograft for ACL reconstruction, with less donor site morbidity than traditional grafts like bone-patellar tendon-bone and hamstring tendons. This study evaluates donor site ankle morbidity after PLT harvesting for ACL reconstruction.

Materials and Methods: A retrospective observational study at an Indian Government Medical College and Hospital from February 2023 to October 2024 involved 56 patients with symptomatic ACL tears who underwent arthroscopic ACL reconstruction using PLT grafts. Donor site morbidity was assessed preoperatively and postoperatively using the visual analog scale for foot and ankle (VAS-FA) and American orthopaedic Foot and Ankle society (AOFAS) scores at 14 days, 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Data were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance.

Results: Participants had a mean age of 36.8 years and an average injury duration of 13.3 months. Donor site morbidity occurred in 66.1% of patients, mainly as mild pain and swelling, which improved significantly over time. VAS-FA scores dropped from 7.52 preoperatively to 2.05 at 6 months, and AOFAS scores increased from 54.8 to 80.0. Chronic injury duration (over 16 months) was associated with poorer recovery, while preoperative pain, gender, graft size, and weight-bearing duration had no significant impact on recovery outcomes.

Conclusion: PLT harvesting for ACL reconstruction leads to minimal donor site morbidity, with mild pain and swelling that improve over time. PLT grafts offer a promising alternative to traditional autografts, providing comparable outcomes and fewer complications. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to confirm these results.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, peroneus longus tendon, visual analog scale for foot and ankle, American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society score.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries represent one of the most common and debilitating conditions encountered in orthopedic and sports medicine. The ACL plays a crucial role in maintaining knee joint stability, and its rupture often necessitates surgical reconstruction to restore normal function and prevent long-term complications, such as osteoarthritis and meniscus damage [1]. Over the past few decades, various autograft options have been explored for ACL reconstruction, including the bone-patellar tendon-bone graft and hamstring tendon (HT) graft. While these grafts have demonstrated favorable outcomes, concerns regarding donor site morbidity, such as anterior knee pain and muscle weakness, have driven the search for alternative graft sources [2]. The peroneus longus tendon (PLT) has emerged as a promising autograft option for ACL reconstruction. Several studies have highlighted the biomechanical strength of the PLT, noting its comparable tensile properties to the native ACL and other commonly used grafts [3,4]. In addition, the PLT offers the advantage of minimal donor site morbidity and reduced risk of quadriceps or hamstring muscle weakness [5]. Recent clinical studies and systematic reviews have demonstrated that ACL reconstruction using PLT results in satisfactory knee stability and functional outcomes, comparable to or exceeding those achieved with traditional autografts [6,7]. Research by Agarwal et al. and He et al. has shown that patients undergoing PLT-based ACL reconstruction experience significant improvements in international knee documentation committee and Lysholm scores, with no significant differences in donor site pain or functional deficits [3,4]. Furthermore, comparative studies have indicated that PLT grafts provide larger graft diameters, which may contribute to enhanced graft strength and longevity [8,9]. This attribute makes the PLT particularly suitable for patients with larger body frames or those undergoing revision ACL reconstruction [10]. Despite these promising findings, some studies have reported minor ankle-related complications, such as reduced eversion and plantarflexion strength at the donor site [11,12]. However, these effects are generally transient and do not significantly impact overall patient satisfaction or return to physical activity [13]. In light of the growing body of evidence, the PLT is increasingly being recognized as a viable and effective alternative for ACL reconstruction, offering comparable outcomes to traditional autografts while mitigating the risk of donor site complications [12,13]. The objective of the study is to assess the clinical and functional assessment of donor site ankle morbidity after harvesting PLT graft for arthroscopic ACL reconstruction.

The retrospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedics of a Government Medical College and Hospital in India between February 2023 and October 2024. The study aimed to evaluate the donor site ankle morbidity in patients undergoing arthroscopic ACL reconstruction using PLT graft.

Ethical considerations

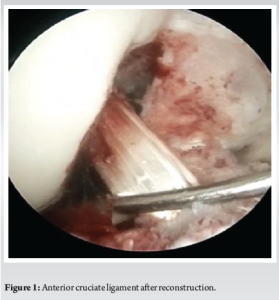

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Research Committee. The study included 56 patients with symptomatic partial or complete ACL tears requiring arthroscopic reconstruction who underwent surgery in the specified duration. Patients were selected based on specific inclusion criteria: They were ages between 18 and 50 years and whose follow up data was available. Exclusion criteria included pre-existing ankle deformity, professional athletes, history of ankle or foot pathology, prior ankle surgeries, and patients with systemic illnesses that could affect healing or rehabilitation. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were fully briefed on the study’s objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits. The methodology involved preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative assessments to evaluate donor site ankle morbidity. Clinical evaluation included the use of the visual analogue scale for foot and ankle (VAS-FA) score to assess pain and functional status, and the American orthopaedic foot and ankle society (AOFAS) score for a comprehensive ankle function evaluation. All patients underwent arthroscopic ACL reconstruction using a PLT graft (Fig. 1).

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure involves harvesting the autogenous PLT through a vertical incision near the distal fibula. The tendon is exposed, and the distal portion is sutured to the peroneus brevis tendon. The proximal end is sutured with a non-absorbable suture, then harvested using a tendon stripper. The graft is pre-tensioned, tripled for thickness, and sized for the femoral and tibial tunnels. Arthroscopic portals (anterolateral, anteromedial, posteromedial, and superolateral) are used for visualization and preparation of the femoral and tibial tunnels. The graft is passed through the tunnels and fixed with Endobutton and interference screw. Postoperative rehabilitation included physiotherapy and strengthening exercises, with weight-bearing restrictions for the first 2 weeks, followed by progressive loading. Follow-up evaluations were conducted at 14 days, 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months postoperatively, during which VAS-FA and AOFAS scores were recorded to assess functional outcomes and donor site morbidity. Outcome assessments were conducted by independent evaluators who were blinded to the surgical details and patient grouping. This blinding was maintained throughout the follow-up period to minimize observer and performance bias, particularly during the assessment of subjective outcome measures such as VAS-FA and AOFAS scores. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess changes in VAS-FA and AOFAS scores over time. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for paired non-parametric comparisons between timepoints, while repeated measures ANOVA was applied to assess overall trends across multiple timepoints with approximately normal distributions.

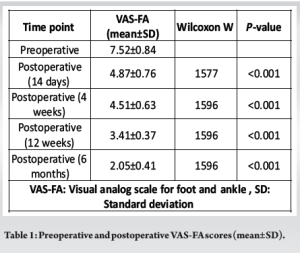

The study included participants with a mean age of 36.8 years (± 6.98) and an average injury duration of 13.3 months (± 4.35). Full weight-bearing was attained at an average of 6.43 weeks (± 0.87), with a mean graft size of 8.34 mm (± 0.695). Males constituted 51.8% of the study cohort. A total of thirty-seven participants (66.1%) reported experiencing complications following tendon harvesting, with twenty-seven individuals indicating mild pain and others reporting swelling at the donor site. Table 1 presents the preoperative visual analog scale for functional assessment (VAS-FA) scores, which averaged 7.52 ± 0.84, indicating a considerable level of discomfort at the donor site. Postoperative scores demonstrated improvement at all follow-up intervals: 4.87 ± 0.76 at 14 days, 4.51 ± 0.63 at 4 weeks, 3.41 ± 0.37 at 12 weeks, and 2.05 ± 0.41 at 6 months. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests revealed statistically significant improvements at each time point (P < 0.001), thereby reflecting a reduction in donor site morbidity.

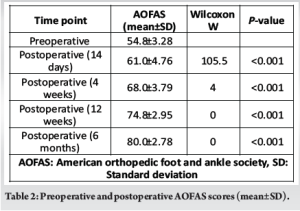

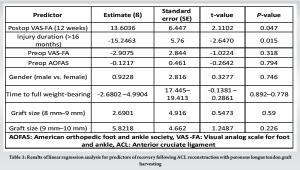

As presented in Table 2, the average preoperative AOFAS scores were 54.8 ± 3.28, which suggests the presence of functional limitations in the donor ankle. Postoperative assessments demonstrated significant improvements at all evaluated time points: 14 days (61.0 ± 4.76), 4 weeks (68.0 ± 3.79), 12 weeks (74.8 ± 2.95), and 6 months (80.0 ± 2.78). All observed changes were statistically significant (P < 0.001). As indicated in Table 3, the postoperative Visual Analog Scale for Functional Assessment (VAS-FA) at 12 weeks (β = 13.6036, P = 0.047) serves as a significant predictor of recovery. This finding underscores the importance of pain management and functional improvement at 12 weeks post-surgery as strong indicators of long-term recovery following tendon graft harvesting. The duration of the injury, particularly when exceeding 16 months (β = −15.2463, P = 0.015), significantly influences the outcome, with longer injury durations associated with poorer recovery. This suggests that the chronicity of the injury may adversely affect the healing process and overall recovery. Conversely, preoperative pain (VAS-FA) (β = −2.9075, P = 0.318) and preoperative function (AOFAS) (β = −0.1217, P = 0.794) were not identified as significant predictors, indicating that early assessments of pain and function may have less impact on recovery compared to later postoperative evaluations. In addition, gender (β = 0.9228, P = 0.746), time to full weight-bearing (β = −2.6802–4.9904, P = 0.892–0.778), and graft size (β = 2.6901–5.8218, P = 0.590–0.226) were also found to be non-significant predictors, suggesting that these factors do not substantially affect the recovery process following ACL reconstruction utilizing PLT graft harvesting.

Our study included participants with a mean age of 36.8 years and an average injury duration of 13.3 months. Full weight-bearing was achieved in 6.43 weeks, with a mean graft size of 8.34 mm. Donor-site morbidity was reported by 66.1% of participants, primarily as mild pain and swelling. Postoperative improvements in VAS-FA and AOFAS scores indicated reduced discomfort and functional limitations. The VAS-FA at 12 weeks strongly predicted recovery, while chronic injuries (over 16 months) negatively affected outcomes. Gender, weight-bearing duration, and graft size were not significant recovery predictors. A study on donor site morbidity after harvesting the PLT for ACL reconstruction found reduced postoperative ankle range of motion compared to preoperative levels and the contralateral side, but no significant impact on ankle strength or functional outcomes, indicating minimal donor-site morbidity [14]. Another study showed that PLT grafts had a larger diameter and shorter harvesting time than HT grafts, with patients returning to sports earlier and reporting better knee outcomes at 6 months. However, there were no significant differences in graft rupture or long-term outcomes at 24 months, suggesting PLT supports early recovery without compromising long-term success [15]. A long-term study on HT grafts indicated good clinical stability and low failure rates at a median follow-up of 21 years, but nearly half of the patients showed radiographic signs of osteoarthritis, particularly those with meniscectomy [16]. Research on postural control after ACL reconstruction with PLT showed significant improvements in balance 6 months post-surgery, concluding that PLT grafts do not negatively affect postural control [17]. A randomized study by Dwidmuthe et al. [18] found that PLT grafts had longer lengths and shorter surgery times than HT grafts, with similar functional outcomes. PLT grafts had fewer donor-site complications, while HT grafts had more muscle atrophy and sensory changes. Acharya et al. [19] found that while the PLT group had a larger graft diameter and fewer complications, the HT group experienced more persistent thigh pain and paraesthesia, suggesting PLT may offer advantages in donor site complications, though tailored rehabilitation is necessary for optimal recovery. Rajani et al. [20] found that peroneus longus autograft used in ACL reconstruction resulted in excellent functional outcomes and clinical stability, with 90.27% of patients showing no laxity, a mean foot and ankle disability index of 94.8, and good graft uptake on magnetic resonance imaging after 3 years, with minimal donor site morbidity. However, this study has several limitations. Follow-up period in this study was limited to 6 months. Although early functional recovery was well documented, potential late complications such as residual weakness, ankle instability, or degenerative changes could not be assessed. Longer-term follow-up studies are warranted to fully evaluate the durability of functional outcomes and donor site morbidity. The absence of a comparator group, such as patients undergoing ACL reconstruction with hamstring or patellar tendon autografts, restricts the ability to directly compare donor site morbidity and graft efficacy. Future randomized controlled studies comparing PLT grafts with other autograft options would strengthen the comparative evidence. No objective measurements of ankle strength (such as isokinetic dynamometry) were employed. Objective biomechanical assessments would have provided a more precise evaluation of functional impairments following PLT harvesting.

Our study highlights that harvesting the PLT for ACL reconstruction results in minimal donor site morbidity, with 66.1% of participants reporting mild pain and swelling that significantly improved over time. Functional assessments using the VAS-FA and AOFAS scores showed considerable recovery by 12 weeks, with continued improvement at 6 months. Factors such as preoperative pain and function were not significant predictors of recovery, but chronic injuries (lasting more than 16 months) negatively affected outcomes. Gender, time to full weight-bearing, and graft size also had no significant impact on recovery. These findings suggest that PLT grafts provide a promising alternative to traditional autografts for ACL reconstruction, offering comparable functional outcomes while reducing donor site complications. Further research with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up is needed to confirm these results and assess long-term outcomes, but overall, PLT harvesting is an effective and viable option for ACL reconstruction with minimal impact on donor ankle function and recovery.

PLT grafts offer a reliable and safe alternative for ACL reconstruction, with minimal donor site morbidity. Although mild ankle pain and swelling are common early postoperative complications, they tend to resolve significantly by 6 months, without affecting functional outcomes. PLT harvesting can be considered a viable autograft option, particularly in patients requiring larger grafts or those undergoing revision ACL surgery.

References

- 1.Wiradiputra AE, Febyan, Aryana GN. Peroneus longus tendon graft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2021;83:106028. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Goyal T, Paul S, Choudhury AK, Sethy SS. Full-thickness peroneus longus tendon autograft for anterior cruciate reconstruction in multi-ligament injury and revision cases: Outcomes and donor site morbidity. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2023;33:21-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Agarwal A, Singh S, Singh A, Tewari P. Comparison of functional outcomes of an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction using a peroneus longus graft as an alternative to the hamstring tendon graft. Cureus 2023;15:e37273. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.He J, Tang Q, Ernst S, Linde MA, Smolinski P, Wu S, et al. Peroneus longus tendon autograft has functional outcomes comparable to hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021;29:2869-79. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Butt UM, Khan ZA, Amin A, Shah IA, Iqbal J, Khan Z. Peroneus longus tendon harvesting for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. JBJS Essent Surg Tech 2022;12:e20.00053. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Marín Fermín T, Hovsepian JM, Symeonidis PD, Terzidis I, Papakostas ET. Insufficient evidence to support peroneus longus tendon over other autografts for primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. J ISAKOS 2021;6:161-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Zhang S, Cai G, Ge Z. The efficacy of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon and its impact on ankle joint function. Orthop Surg 2024;16:1317-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Joshi S, Shetty UC, Salim MD, Meena N, Kumar RS, Rao VK. Peroneus longus tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A safe and effective alternative in nonathletic patients. Niger J Surg 2021;27:42-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Keyhani S, Qoreishi M, Mousavi M, Ronaghi H, Soleymanha M. Peroneus longus tendon autograft versus hamstring tendon autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A comparative study with a mean follow-up of two years. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2022;10:695-701. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Hossain GM, Islam MS, Khan MM, Islam MR, Rahman SM, Jahan MS, et al. A prospective study of arthroscopic primary ACL reconstruction with ipsilateral peroneus longus tendon graft: Experience of 439 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102:e32943. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Bi M, Zhao C, Zhang Q, Cao L, Chen X, Kong M, et al. All-inside anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using an anterior half of the peroneus longus tendon autograft. Orthop J Sports Med 2021;9:2325967121991226. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Viswanathan VK, Iyengar KP, Jain VK. The role of peroneus longus (PL) autograft in the reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): A comprehensive narrative review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2024;49:102352. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Punnoose DJ, Varghese J, Theruvil B, Thomas AB. Peroneus longus tendon autografts have better graft diameter, less morbidity, and enhanced muscle recuperation than hamstring tendon in ACL reconstruction. Indian J Orthop 2024;58:979-86. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Ertilav D, Ertilav E, Dirlik GN, Barut K. Donor site morbidity after removal of full-thickness peroneus longus tendon graft for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: 4-year follow-up. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 2024;91:170-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Saeed UB, Ramzan A, Anwar M, Tariq H, Tariq H, Yasin A, et al. Earlier return to sports, reduced donor-site morbidity with doubled peroneus longus versus quadrupled hamstring tendon autograft in ACL reconstruction. JBJS Open Access 2023;8:e23.00051. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Hagemans FJ, Jonkers FJ, Van Dam MJ, Von Gerhardt AL, Van der List JP. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon graft and femoral cortical button fixation at minimum 20-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2020;48:2962-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Sahoo PK, Sahu MM. Analysis of postural control following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with ipsilateral peroneus longus tendon graft. Malays Orthop J 2023;17:133-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Dwidmuthe S, Roy M, Bhikshavarthi Math SA, Sah S, Bhavani P, Sadar A. Functional outcome of single-bundle arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using peroneus longus graft and hamstring graft: An open-label, randomized, comparative study. Cureus 2024;16:e60239. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Acharya K, Mody A, Madi S. Functional outcomes of anatomic single bundle primary ACL reconstruction with peroneus longus tendon (without a peroneal tenodesis) versus hamstring autografts. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2024;12:116-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Rajani AM, Shah UA, Mittal AR, Rajani A, Punamiya M, Singhal R. Functional and clinical outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with peroneus longus autograft and correlation with MRI after 3 years. J Orthop 2022;34:215-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]