Digital infrared thermography imaging (DITI) offers a promising, non-invasive approach to detect physiological changes in degenerative spinal disorders by analyzing thermal asymmetry associated with inflammation and nerve dysfunction.

Dr. Sathish Muthu, Department of Spine Surgery, Orthopaedic Research Group, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: drsathishmuthu@gmail.com

Abstract Degenerative spinal disorders are a growing concern, affecting millions worldwide and often leading to chronic pain, functional impairment, and reduced quality of life. Traditional imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans primarily focus on structural abnormalities, limiting real-time physiological assessments. Digital infrared thermography imaging (DITI) has emerged as a promising non-invasive diagnostic tool that evaluates thermal emissions from the body, offering valuable insights into musculoskeletal dysfunction. This review explores the principles of DITI, its application in diagnosing degenerative spinal disorders, and its clinical implications. DITI operates on the principle that physiological disturbances – such as inflammation, neuropathy, and vascular irregularities –alter skin temperature distribution, which can be captured using infrared technology. It has shown promise in detecting conditions such as herniated discs, spinal stenosis, and facet joint degeneration by identifying abnormal thermal asymmetry. While DITI offers advantages such as real-time functional assessment, cost-effectiveness, and early disease detection, challenges related to standardization, environmental variability, and specificity persist. Recent advancements, including artificial intelligence-driven thermal analysis and hybrid imaging approaches, are improving DITI’s diagnostic precision and clinical utility. Establishing standardized protocols for environmental control, patient preparation, and image validation is crucial for ensuring reproducibility in spinal evaluations. As research progresses, integrating DITI with conventional imaging methods may enhance its role in clinical practice, optimizing diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes for patients with degenerative spinal disorders.

Keywords: Spine, thermography, digital infrared thermography imaging, degenerative, diagnosis, prognosis.

Degenerative spinal disorders encompass a range of conditions affecting the vertebral structures, intervertebral discs, and adjacent tissues, leading to chronic pain and functional limitations with multiple risk factors contributing to its development [1,2]. Over time, these conditions contribute to musculoskeletal imbalances, nerve compression, and altered biomechanical stress distribution within the spinal column [3]. Traditional imaging techniques, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, and X-rays, have served as primary diagnostic tools for evaluating spinal pathology [4]. However, their reliance on anatomical visualization often limits functional assessment, particularly in early disease detection. Digital infrared thermography imaging (DITI) has emerged as a promising, non-invasive diagnostic approach that captures temperature variations linked to underlying physiological changes [5,6]. By analyzing thermal emissions from the body, DITI offers valuable insights into inflammatory responses, nerve dysfunction, and vascular irregularities associated with degenerative spinal disorders [7]. This review evaluates the fundamental principles of DITI, its clinical applications in spinal pathology, diagnostic accuracy, advantages, limitations, and recent advancements in thermographic imaging.

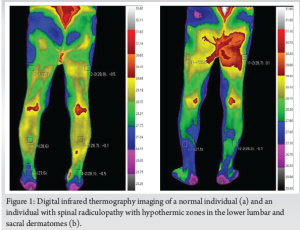

DITI operates on the principle that physiological disturbances – such as inflammation, neuropathy, and circulatory changes – affect heat distribution on the skin’s surface. Infrared cameras detect these temperature variations, producing thermographic maps that can be analyzed for diagnostic purposes [8]. In spinal disorders, the presence of physiological disturbances, such as neuropathy, inflammation, or circulatory irregularities, alters normal thermal balance [5,6]. When a nerve root becomes compressed due to degenerative changes (e.g., disc herniation or spinal stenosis), the affected region may show hypothermic patterns, indicating reduced blood flow and metabolic activity. Conversely, areas of hyperthermia suggest ongoing inflammatory processes, wherein tissue irritation leads to increased vascularization and localized heat production [8,9]. The key feature of thermographic evaluation is identifying thermal asymmetry, which is the abnormal variations in temperature between corresponding anatomical regions. In healthy individuals, temperature distribution across symmetrical body parts remains relatively uniform. However, in patients with spinal dysfunction, one side may exhibit heightened temperature due to inflammation, whereas the opposing side may show lower thermal emissions, suggesting compromised circulation as shown in Fig. 1. Studies have demonstrated that hyperthermia often aligns with inflamed nerve roots, whereas hypothermia is indicative of vascular insufficiency resulting from nerve compression. Such thermal imbalances provide critical clues regarding the severity, location, and nature of spinal dysfunction [10,11].

Since DITI depends on detecting subtle variations in skin temperature, maintaining a controlled environment and following strict patient preparation protocols are essential to ensure accurate and reproducible diagnostic results [5]. Room conditions play a crucial role, as external temperature fluctuations, humidity levels, and air movement can interfere with thermal readings. The imaging should be conducted in a temperature-controlled room, ideally maintained between 18°C and 22°C, to minimize external influences. Humidity and airflow must also be regulated to prevent artificial cooling or heating effects on the patient’s skin. Lighting conditions influence the results since direct exposure to sunlight or infrared heat sources can skew thermal measurements. Therefore, thermography rooms should be shielded from external heat-emitting sources and designed to minimize unwanted infrared interference. Equally important is patient preparation, which ensures that observed temperature variations reflect actual physiological changes rather than external artefacts. Before undergoing thermographic imaging, patients must follow specific guidelines designed to eliminate transient thermal fluctuations. Physical activity should be avoided for at least 24 h before the procedure, as exercise increases circulation and temporarily elevated skin temperature. In addition, patients should refrain from consuming hot beverages, caffeine, alcohol, and smoking a few hours before the test, as these factors can cause vascular responses that lead to artificial temperature variations. Topical applications such as lotions and creams must be avoided on the day of imaging, as they can act as insulators and alter heat distribution. To ensure consistency in measurements, patients should acclimate to the controlled room temperature for at least 15–20 min before imaging, allowing their skin temperature to stabilize naturally. During the imaging process, standardized posture and positioning should be strictly maintained to avoid asymmetry that could affect temperature readings. Image validation is another crucial step in thermographic evaluation. To ensure reliable interpretation, infrared cameras must be calibrated before each imaging session to maintain accuracy in temperature measurements. Reference temperature markers within the imaging frame help the system adjust for ambient conditions, preventing misleading variations. Conducting multiple imaging sessions at different intervals further enhances reliability by confirming thermal consistency and ruling out transient fluctuations. Advances in artificial intelligence (AI)-driven thermal analysis software have improved accuracy in detecting abnormal thermal patterns, refining the diagnostic utility of DITI. In addition, thermal normalization techniques are applied to standardize readings, ensuring that final temperature maps align with established clinical diagnostic criteria. By integrating standardized environmental controls, patient preparation protocols, and image validation techniques, DITI could be made a reliable and clinically meaningful diagnostic tool. These measures help mitigate external influences, ensuring that thermal assessments accurately reflect underlying physiological conditions rather than external variables.

DITI has been explored in multiple spinal conditions, demonstrating its potential for early diagnosis and functional assessment [12]. A variety of studies have documented conflicting data on the effectiveness of infrared thermography in evaluating different types of spinal pathologies [13,14]. One of the primary applications of DITI is in the diagnosis of herniated discs and radiculopathy, where asymmetric thermal patterns along affected dermatomes indicate nerve root compression [12,14,15] as shown in Fig. 1. Spinal stenosis, particularly cases presenting with neurogenic claudication, has been assessed through infrared imaging to identify vascular changes contributing to symptoms. In addition, spondylolisthesis has been linked to distinct thermographic abnormalities, aiding in the early identification of biomechanical instability. DITI has also proven useful in evaluating facet joint syndrome and spinal osteoarthritis, where localized inflammation results in measurable temperature deviations [15,16]. Furthermore, infrared imaging has been applied in post-surgical assessment, particularly in monitoring adjacent segment disease following lumbar fusion procedures [16] and also in prognosticating the outcome by normalization of the symmetrical thermographic pattern postoperatively [16].

The diagnostic accuracy of DITI varies based on the spinal disorder being assessed and the methodology used for thermographic analysis. Some studies indicate that DITI achieves sensitivity levels of up to 90% in detecting nerve-related dysfunctions, making it a reliable screening tool [12,13]. However, specificity remains a challenge, as external factors such as ambient temperature, patient positioning, and physiological variability can influence readings [5,11,12]. Comparative evaluations have demonstrated that DITI can effectively complement MRI and electromyography in assessing inflammatory responses and nerve dysfunction [12,16]. While thermography lacks the anatomical precision of conventional imaging modalities, its ability to highlight physiological changes contributes to a holistic diagnostic approach [12,17]. However, there exists a lack of specificity in the condition responsible for the changes noted in the thermographic pattern, which needs further analysis.

DITI offers several benefits in spinal diagnostics, making it an attractive adjunctive tool. It is non-invasive, eliminating the risks associated with radiation exposure and contrast agents [6]. In addition, it allows real-time functional assessment, capturing dynamic physiological changes rather than static anatomical abnormalities [6]. Furthermore, DITI is cost-effective, providing a lower-cost alternative to MRI and CT scans while maintaining diagnostic relevance [12,16,17]. Its early detection capabilities help identify abnormal thermal distributions before significant structural damage occurs, facilitating timely intervention [18]. Finally, thermography is useful in monitoring progression and treatment response, enabling clinicians to evaluate the impact of therapeutic interventions [18,13]. Having said all that, thermographic imaging is subjective to a lot of other local factors that determine the specificity; hence, standardization of the procedure remains crucial to improve its diagnostic capability.

Despite its promising applications, DITI has several limitations. Environmental factors such as room temperature and humidity can influence thermographic readings, leading to variability in diagnostic outcomes, which, however, could be controlled by standardization of the procedure. In addition, the lower specificity for structural diagnosis means that DITI cannot replace conventional imaging techniques for detailed anatomical assessments [6]. There is also a lack of standardized diagnostic thresholds, making interpretation of results subjective and dependent on clinical expertise. Moreover, patient-specific factors, including skin temperature regulation, body fat distribution, and underlying vascular conditions, can affect the accuracy of infrared imaging.

Recent advancements in DITI have focused on improving diagnostic precision through machine learning algorithms and AI-driven thermal pattern recognition. These innovations enable more accurate differentiation between pathological and physiological thermal variations, refining diagnostic capabilities [12]. Hybrid imaging approaches that integrate DITI with MRI and ultrasound have also shown promise in enhancing diagnostic accuracy. In addition, developments in portable infrared devices have made thermographic assessments more accessible for clinical and research applications.

DITI represents a valuable diagnostic tool for degenerative spinal disorders, offering functional insights that complement conventional imaging techniques. While challenges related to standardization and specificity remain, advancements in technology continue to enhance the clinical utility of thermography. Further research is necessary to establish standardized diagnostic thresholds, refine AI-driven analyses, and integrate DITI into multimodal diagnostic frameworks. As technology evolves, infrared thermography holds the potential to improve early detection and patient outcomes in spinal medicine.

References

- 1.Corluka S, Muthu S, Yoon T, Cunha C, Gary M, Vadala G, et al. Decompression-only for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis - what are the risk for failure? - A systematic review. Global Spine J 2025;21925682251342230. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Gallucci M, Limbucci N, Paonessa A, Splendiani A. Degenerative disease of the spine. Neuroimaging Clin North Am 2007;17:87-103. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Chen X, Xu L, Qiu Y, Chen ZH, Zhou QS, Li S, et al. Higher improvement in patient-reported outcomes can be achieved after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for clinical and radiographic degenerative spondylolisthesis classification type d degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. World Neurosurg 2018;114:e293-300. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Sasiadek MJ, Bladowska J. Imaging of degenerative spine disease--the State of the art. Adv Clin Exp Med 2012;21:133-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Diakow PR, Ouellet S, Lee S, Blackmore EJ. Correlation of thermography with spinal dysfunction: Preliminary results. J Can Chiropr Assoc 1988;32:77-80. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Kim TS, Hur JW, Ko SJ, Shin JK, Park JY. Thermographic findings in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis before and after walking. Asian J Pain 2018;4:25-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Plaugher G. Skin temperature assessment for neuromusculoskeletal abnormalities of the spinal column. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992;15:365-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Hoffman RM, Kent DL, Deyo RA. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of thermography for lumbar radiculopathy. A meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16:623-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.BenEliyahu DJ. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of thermography for lumbar radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17:456-7; author reply 457-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Roggio F, Petrigna L, Trovato B, Zanghì M, Sortino M, Vitale E, et al. Thermography and rasterstereography as a combined infrared method to assess the posture of healthy individuals. Sci Rep 2023;13:4263. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.So YT, Olney RK, Aminoff MJ. A comparison of thermography and electromyography in the diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. Muscle Nerve 1990;13:1032-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Liu H, Zhu Z, Jin X, Huang P. The diagnostic accuracy of infrared thermography in lumbosacral radicular pain: A prospective study. J Orthop Surg Res 2024;19:409. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Pawl RP. Thermography in the diagnosis of low back pain. Neurosurg Clin N Am 1991;2:839-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.So YT, Aminoff MJ, Olney RK. The role of thermography in the evaluation of lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurology 1989;39:1154-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Polidori G, Kinne M, Mereu T, Beaumont F, Kinne M. Medical infrared thermography in back pain osteopathic management. Complement Ther Med 2018;39:19-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Chafetz N, Wexler CE, Kaiser JA. Neuromuscular thermography of the lumbar spine with CT correlation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;13:922-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Raskin MM, Martinez-Lopez M, Sheldon JJ. Lumbar thermography in discogenic disease. Radiology 1976;119:149-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Lubkowska A, Pluta W. Infrared thermography as a non-invasive tool in musculoskeletal disease rehabilitation-the control variables in applicability-a systematic review. Appl Sci 2022;12:4302. [Google Scholar | PubMed]