The use of custom 3D-printed scaffolds (Osteopore®) may be considered in the management of critical-sized bone defects in calcaneal fractures

Ping Yen Yeo, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Singapore. E-mail: pingyenyeo@gmail.com

Introduction: Intra-articular calcaneal fractures are generally treated with open reduction and internal fixation in order to restore calcaneal anatomy as well as subtalar and calcaneocuboid joint congruency. Bone loss is common due to the impaction of cancellous bone beneath the posterior facet as a result of axial loading. Critical-sized bone defects are commonly addressed with the Masquelet “induced membrane technique” incorporating autogenous or allogenous bone graft. Synthetic bone scaffolds are readily available and customizable through three-dimensional (3D) printing. This case report describes the novel use of a custom 3D-printed polycaprolactone-tricalcium phosphate (PCL-TCP) scaffold (Osteopore®) in conjunction with the Masquelet technique in the management of a critical-sized bone defect for a patient with an open intra-articular calcaneal fracture.

Case Report: A gentleman sustained an open right calcaneal intra-articular fracture after a fall from height. The fracture was initially stabilized with a joint spanning external fixator while the patient underwent multiple surgeries for wound debridement and insertion of cement spacer. The skin defect was covered using a contralateral anterolateral thigh flap and the external fixator was converted to an Ilizarov circular frame 1 month after soft-tissue reconstruction surgery. Ten weeks after the initial injury, a custom scaffold was utilized to fill the bone defect encapsulated by a pseudomembrane formed by the cement spacer from earlier surgeries. Autogenous bone graft and BMAC was harvested from the ipsilateral iliac crest and packed into the scaffold. A cancellous screw was inserted, from the posterior calcaneal tuberosity through the subtalar joint into the talus, to anchor the scaffold. The Ilizarov frame was removed 3 months later. The bone defect was adequately addressed resulting in good restoration of calcaneal anatomy as well as joint congruency. At 3 years post-operation, the patient is ambulant without walking aids, reports minimal pain, and remains infection-free. Repeat radiographs show callus formation, bony fusion, and graft incorporation.

Conclusion: This case report shows promising early results from the use of a custom PCL-TCP scaffold (Osteopore®) in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique in the management of a critical-sized bone defect for a patient with an open intra-articular calcaneal fracture.

Keywords: Orthopedics, trauma, critical bone defect, calcaneal fracture, bone scaffold, Masquelet.

Calcaneal fractures are challenging to treat and associated with high morbidity and socioeconomic costs [1-3]. Displaced intra-articular fractures are generally treated with open reduction and internal fixation to restore calcaneal width, height, and alignment as well as subtalar and calcaneocuboid joint congruency [4]. Critical-sized bone defects are common in intra-articular calcaneal fractures due to the impaction of cancellous bone beneath the posterior facet as a result of the axial loading mechanism of injury [2,5]. While controversial, such bone defects are commonly addressed with the use of autogenous and allogenous bone grafts [3]. Synthetic bone scaffolds have gained traction in recent decades due to their abundant availability and ease of customization facilitated by technological advances such as in three-dimensional (3D) printing [6-8]. This case report describes the novel use of a Food and Drug Administration and Health Sciences Authority-approved custom biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL)-tricalcium phosphate (TCP) synthetic bone scaffold (Osteopore®) in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique in the management of a critical-sized bone defect in a patient with an open intra-articular calcaneal fracture.

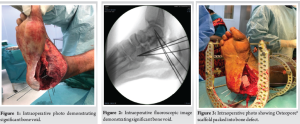

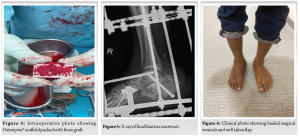

A 45-year-old gentleman sustained a Gustilo-Anderson 3B open right calcaneal intra-articular fracture after a fall from height of approximately 3 m. There were no other bony injuries besides the calcaneal fracture. The calcaneal fracture was initially stabilized with a joint spanning external fixator while the patient underwent multiple surgeries for wound debridement. K-wires were used to reconstruct the subtalar joint, and a cement spacer was utilized to fill the significant bone void (Fig. 1 and 2). Twenty days after the initial injury, the large skin defect was covered using a contralateral anterolateral thigh flap. The external fixator was converted to an Ilizarov circular frame 1 month after soft-tissue reconstruction surgery. Approximately 10 weeks after the initial injury, a biodegradable PCL-TCP synthetic bone scaffold (Osteopore®) was utilized to fill the critical-sized bone defect encapsulated by a pseudomembrane formed by the cement spacer from earlier surgeries (Fig. 3). The scaffold was a custom 3D-printed cuboid-shaped block measuring approximately 8 × 4 × 4 cm which was further cut to fit the exact bony defect. The approximate size of the scaffold needed was based on estimates of the size of the bone defect from pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scans. Autogenous bone graft and bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) was harvested from the ipsilateral iliac crest and packed into the porous scaffold (Fig. 4). A 6.5 mm cancellous screw was inserted, from the posterior calcaneal tuberosity through the subtalar joint into the talus, to anchor the scaffold (Fig. 5). The Ilizarov circular frame was removed 3 months later. Subsequently, the patient underwent elective removal of the right calcaneal screw and liposuction-assisted debulking of right foot flap 1 year postoperatively.

There was good restoration of calcaneal width, height, and alignment as well as subtalar and calcaneocuboid joint congruency. The critical-sized bone defect was adequately addressed with the use of the synthetic scaffold in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique incorporating autogenous iliac crest bone graft and BMAC. At 3 years post-operation, the patient is ambulant without walking aids, reports minimal pain, and remains infection-free. The surgical wounds are well healed, and the flap is healthy (Fig. 6). Repeat radiographs and CT scans show callus formation, bony fusion, and graft incorporation (Fig. 7 and 8). While there is some degree of interval collapse of the calcaneal height as well as subtalar and calcaneocuboid arthritis, the use of the synthetic scaffold provided a significant restoration of height as compared to the index injury radiographs.

Historically, calcaneal fractures were almost exclusively treated conservatively and resulted in poor outcomes [9]. Despite improved understanding of fracture anatomy and advancements in radiological and surgical capabilities, there is still no consensus on optimal treatment. Gougoulias et al. highlighted uncertainty whether general health outcome measures, injury specific scores and radiographic parameters improve with operative management, and whether the benefits of surgery outweigh the risks [10]. However, other studies have found better restoration of anatomy [11], improved patient-reported visual analogue pain, and functional scores such as the 36-item short form survey (SF-36) score [12], improved shoe-wear and walking [1], as well as reduced incidence of post-traumatic subtalar arthritis [1,13] with operative management. Amidst this debate, there is an apparent trend toward operative management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures [12]. The decision for operative management in this case was made because it involved an open intra-articular calcaneal fracture with a critical-sized bone defect. Bone loss in calcaneal fracture is a common problem arising from the impaction of cancellous bone beneath the posterior facet as a result of the axial loading mechanism of injury [2,5]. There is further controversy over whether bone grafting is necessary, with proponents citing improved bone healing and better mechanical strength [14,15], while opponents highlight high infection rates, donor site morbidity, increased pain, and good healing with internal fixation even without bone grafting due to high calcaneal vascularity [16-19]. A recent meta-analysis concluded that further substantiation is required for the routine use of bone graft in operative management of calcaneal fractures due to the lack of significant differences in restoration of calcaneal height, American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society hindfoot scores, Maryland foot evaluation, and rate of wound infection [20]. When the degree of bone loss is significant enough to cause a critical-sized bone defect – defined as those that are unlikely to heal spontaneously within the patient’s lifetime without intervention – bone grafting is often necessary [21]. In this case, there was a critical-sized bone defect in the calcaneum, and local vascularity was disrupted due to the significant soft-tissue injury. Various techniques have been described to address critical-sized bone defects. As bone healing requires osteogenesis, osteoinduction, and osteoconduction [22], techniques are often combined to maximize success. The Masquelet “induced membrane” technique is a two-stage procedure that first uses a cement spacer to induce the formation of an osteogenic and osteoinductive fibrous membrane followed by bone grafting [21]. Autogenous bone grafts such as cancellous bone graft from the iliac crest remain the preferred choice as an osteogenic bone void filler, while structural grafts such as a free vascularized fibula grafts provide additional osteoconductivity. Allogenous bone grafts are an excellent alternative due its availability and abundance. Specific to the management of critical-sized bone defects in calcaneal fractures, the use of osteoconductive synthetic bone-graft substitutes such as TCP products has yielded good results [15,23-25], while circumventing the common problems with allografts such as host reaction to foreign antigens and the risk of disease transmission [21,26,27], or autografts such as donor site morbidity and pain [17,28]. Platelet-rich-plasma has also been used in addition to allografts to promote osteoinduction [29]. In recent decades, synthetic scaffolds are becoming increasingly popular due to the ability to customize them using 3D-printing in order to promote osteoconduction for large segmental bone defect [30,31]. Scaffolds serve as carriers for bone graft and act as templates for tissue growth and remodeling, optimizing the physical environment for bone regeneration [32]. PCL is a popular biopolymer for synthetic scaffolds due to its excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability [33]. The use of PCL-TCP scaffolds and meshes has been well-described in ophthalmic surgery [34], neurosurgery [35], and craniofacial surgery [36]. In the field of orthopedic surgery, Kobbe et al. described an effective amalgamation of these techniques in the managing a critical-sized bone defect in a patient with an open femoral shaft fracture. A patient-specific PCL-TCP scaffold (Osteopore®) that fitted the anatomical defect and intramedullary nail used for fixation was utilized in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique involving autogenous bone graft harvested using the reamer-irrigator-aspirator system and bone morphogenetic protein-2. At 12 months post-operation, radiographs showed shows advanced bony fusion and bone formation inside and outside the fully interconnected scaffold architecture [37]. Laubach et al. also published good early outcomes from the use of scaffold guided bone regeneration using customized synthetic scaffolds (Osteopore®) combined with autologous bone grafting in four patients with complex post-traumatic long bone defects [32]. Post-operative radiographs and/or CT scans showed bony consolidation and scaffold incorporation, and all four patients were able to ambulate pain-free. Similarly, this case report demonstrates the effective use of a custom scaffold in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique involving autogenous bone graft and BMAC in managing a critical-sized bone defect, this time in the context of an open calcaneal fracture. At 3 years post-operation, although there is radiographic collapse of the fracture reduction as well as subtalar and calcaneocuboid arthritis, the patient is ambulant with minimal pain, does not require walking aids, and has returned to work.

This case report shows promising early results from the novel use of a custom biodegradable PCL-TCP synthetic bone scaffold (Osteopore®) in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique in the management of a critical-sized bone defect for a patient with an open intra-articular calcaneal fracture.

Critical bone defects are a common problem in intra-articular calcaneal fractures. When faced with this clinical issue, readers may consider the technique described in this case report. The use of a custom scaffold in conjunction with the Masquelet “induced membrane” technique has been shown to be effective in the management of a calcaneal fracture with critical bone defect.

References

- 1.Brauer CA, Manns BJ, Ko M, Donaldson C, Buckley R. An economic evaluation of operative compared with nonoperative management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:2741-9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barei DP, Bellabarba C, Sangeorzan BJ, Benirschke SK. Fractures of the calcaneus. Orthop Clin North Am 2002;33:263-85, x. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh AK, Vinay K. Surgical treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: Is bone grafting necessary? J Orthop Traumatol 2013;14:299-305. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schepers T. Fixation by open reduction and internal fixation or primary arthrodesis of calcaneus fractures: Indications and technique. Foot Ankle Clin 2020;25:683-95. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thordarson DB, Bollinger M. SRS cancellous bone cement augmentation of calcaneal fracture fixation. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26:347-52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Lim J, Teoh SH. Review: Development of clinically relevant scaffolds for vascularised bone tissue engineering. Biotechnol Adv 2013;31:688-705. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichte P, Pape HC, Pufe T, Kobbe P, Fischer H. Scaffolds for bone healing: Concepts, materials and evidence. Injury 2011;42:569-73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodruff MA, Hutmacher DW. The return of a forgotten polymer-polycaprolactone in the 21st century. Prog Polym Sci 2010;35:1217-56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razik A, Harris M, Trompeter A. Calcaneal fractures: Where are we now? Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr 2018;13:1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gougoulias N, Khanna A, McBride DJ, Maffulli N. Management of calcaneal fractures: Systematic review of randomized trials. Br Med Bull 2009;92:153-67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei N, Yuwen P, Liu W, Zhu Y, Chang W, Feng C, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A meta-analysis of current evidence base. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e9027. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agren PH, Wretenberg P, Sayed-Noor AS. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:1351-7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo X, Li Q, He S, He S. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Foot Ankle Surg 2016;55:821-8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsner A, Jubel A, Prokop A, Koebke J, Rehm KE, Andermahr J. Augmentation of intraarticular calcaneal fractures with injectable calcium phosphate cement: Densitometry, histology, and functional outcome of 18 patients. J Foot Ankle Surg 2005;44:390-5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang SD, Jiang LS, Dai LY. Surgical treatment of calcaneal fractures with use of beta-tricalcium phosphate ceramic grafting. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:1015-9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumgaertel FR, Gotzen L. Two-stage operative treatment of comminuted os calcis fractures. Primary indirect reduction with medial external fixation and delayed lateral plate fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;290:132-41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurie SW, Kaban LB, Mulliken JB, Murray JE. Donor-site morbidity after harvesting rib and iliac bone. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;73:933-8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebraheim NA, Elgafy H, Sabry FF, Freih M, Abou-Chakra IS. Sinus tarsi approach with trans-articular fixation for displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. Foot Ankle Int 2000;21:105-13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grala P, Twardosz W, Tondel W, Olewicz-Gawlik A, Hrycaj P. Large bone distractor for open reconstruction of articular fractures of the calcaneus. Int Orthop 2009;33:1283-8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian H, Guo W, Zhou J, Wang X, Zhu Z. Bone graft versus non-bone graft for treatment of calcaneal fractures: A protocol for meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e24261. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roddy E, DeBaun MR, Daoud-Gray A, Yang YP, Gardner MJ. Treatment of critical-sized bone defects: Clinical and tissue engineering perspectives. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2018;28:351-62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimitriou R, Tsiridis E, Giannoudis PV. Current concepts of molecular aspects of bone healing. Injury 2005;36:1392-404. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Zhang G, Hong J, Lu X, Yuan W. Comparison of percutaneous screw fixation and calcium sulfate cement grafting versus open treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Foot Ankle Int 2011;32:979-85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biggi F, Di Fabio S, D’Antimo C, Isoni F, Salfi C, Trevisani S. Percutaneous calcaneoplasty in displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Traumatol 2013;14:307-10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labbe JL, Peres O, Leclair O, Goulon R, Scemama P, Jourdel F. Minimally invasive treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures using the balloon kyphoplasty technique: Preliminary study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99:829-36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyce T, Edwards J, Scarborough N. Allograft bone. The influence of processing on safety and performance. Orthop Clin North Am 1999;30:571-81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wee J, Thevendran G. The role of orthobiologics in foot and ankle surgery: Allogenic bone grafts and bone graft substitutes. EFORT Open Rev 2017;2:272-80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, Rhim R, Li L, Martha J, Swaim BH, Banco RJ, et al. Prospective study of iliac crest bone graft harvest site pain and morbidity. Spine J 2009;9:886-92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei LC, Lei GH, Sheng PY, Gao SG, Xu M, Jiang W, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma combined with allograft bone in the management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A prospective cohort study. J Orthop Res 2012;30:1570-6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rai B, Oest ME, Dupont KM, Ho KH, Teoh SH, Guldberg RE. Combination of platelet-rich plasma with polycaprolactone-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds for segmental bone defect repair. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007;81:888-99. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Han Q, Wang C, Liu Y, Chen B, Wang J. Porous scaffold design for additive manufacturing in orthopedics: A review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020;8:609. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laubach M, Suresh S, Herath B, Wille ML, Delbrück H, Alabdulrahman H, et al. Clinical translation of a patient-specific scaffold-guided bone regeneration concept in four cases with large long bone defects. J Orthop Translat 2022;34:73-84. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue W, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Polycaprolactone coated porous tricalcium phosphate scaffolds for controlled release of protein for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2009;91:831-8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teo L, Teoh SH, Liu Y, Lim L, Tan B, Schantz JT, et al. A novel bioresorbable implant for repair of orbital floor fractures. Orbit 2015;34:192-200. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velho V, Naik H, Survashe P, Guthe S, Bhide A, Bhople L, et al. Management strategies of cranial encephaloceles: A neurosurgical challenge. Asian J Neurosurg 2019;14:718-24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castrisos G, Gonzalez Matheus I, Sparks D, Lowe M, Ward N, Sehu M, et al. Regenerative matching axial vascularisation of absorbable 3D-printed scaffold for large bone defects: A first in human series. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2022;75:2108-18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobbe P, Laubach M, Hutmacher DW, Alabdulrahman H, Sellei RM, Hildebrand F. Convergence of scaffold-guided bone regeneration and RIA bone grafting for the treatment of a critical-sized bone defect of the femoral shaft. Eur J Med Res 2020;25:70. [Google Scholar]