Regular long-term monitoring, early detection, and timely intervention are essential in managing metallosis and its complications in metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty.

Dr. Jai Thilak, Department in Orthopaedics, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Kochi, Kerala, India. E-mail: jaithilak@aims.amrita.edu

Introduction: Metallosis is a pathological condition associated with the release of metal debris from joint implants, particularly metal-on-metal (MoM) articulations in total hip arthroplasty (THA). The metal debris triggers adverse local tissue reactions, including aseptic lymphocyte-vasculitis-associated lesions (ALVALs), pseudotumor formation, and progressive implant loosening.

Case Report: Case 1 - A 64-year-old male presented with hip pain and limping 15 years after an uncemented MoM THA. Investigations revealed femoral stem loosening. Intraoperatively, dark synovial fluid, necrotic tissue, elevated cobalt, and chromium levels were consistent with metallosis were identified. Revision surgery replaced the components with alternative bearings, and the patient returned to normal activities within a year. Case 2 - A 63-year-old female with bilateral MoM THAs reported similar symptoms 15-year post-surgery. Imaging identified a pseudotumor and femoral loosening. Elevated serum metal ion levels confirmed the diagnosis. Revision surgery revealed ALVAL, and components were replaced with ceramic-on-polyethylene implants, resolving symptoms.

Conclusion: Metallosis poses a significant risk in MoM THA, caused by wear and corrosion, leading to systemic and local tissue damage. Timely diagnosis through clinical evaluation, imaging, and serum metal ion levels is critical for intervention. Revision surgeries are effective in managing metallosis and restoring function. These cases highlight the importance of long-term monitoring and the consideration of alternative bearing surfaces in hip arthroplasty.

Keywords: Metallosis, metal-on-metal, total hip arthroplasty, adverse local tissue reactions, aseptic lymphocyte- vasculitis-associated lesions, adverse local tissue reactions, pseudotumor.

Metal-on-metal (MoM) total hip replacements (THRs) were initially introduced with the promise of superior advantages compared to traditional hip replacement options, such as reduced wear and increased stability due to the MoM articulation [1]. However, increased awareness of adverse effects was noted from metal ions and nanoparticles released by arthroplasty components, notably in large diameter MoM total hip arthroplasties [2]. These components were eventually determined to have revision rates significantly higher, up to 3 times more, compared to modern hip implants [3]. This resulted in a notable decrease in their usage, indicating that despite their initial promise, the drawbacks of MoM articulations outweigh their advantages, leading to a preference for alternative bearing options [3]. Most of these failures result from metal debris being produced, causing adverse reactions in nearby tissues termed adverse local tissue reaction (ALTR) [4]. This encompasses a range of pathological changes, including extensive tissue death, bone erosion, significant fluid accumulation around the hip joint, and the formation of solid or cystic masses near the implant, often referred to as pseudotumor [4]. While originally attributed solely to MoM articulations, there is an increasing association of these nonmalignant and noninfectious masses and ALTRs with other types of total hip arthroplasty (THA) articulations, including metal-on-polyethylene. This is likely due to the release of metal ions from the modular junctions, suggesting a wider problem extending beyond MoM bearings [5]. The enduring success of THA relies on the effective bonding between the patient’s bone and the prosthetic implant which can be achieved through various methods, including the use of cement, or through bone ingrowth or ongrowth. In cementless THA models, the initial stability of the femoral stem is achieved through a press fit between the bone and the implant. However, for long-term stability, it is essential for cancellous bone to undergo osseointegration with the hydroxyapatite (HA)-porous coated stem [6]. One of our case studies has demonstrated a high risk of loosening of previously osseointegrated HA-coated femoral stems when paired with a MoM bearing. The mechanism of loosening appears progressive in nature and related to the MoM bearing, possibly interacting with the HA coating [7]. The elevation of metal ion concentrations, notably chromium and cobalt, has been observed in individuals with MoM articular surface replacements, exceeding normal physiological levels [8].

Case 1

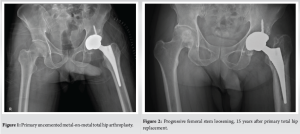

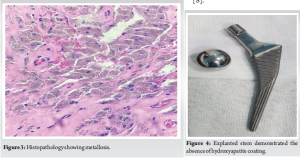

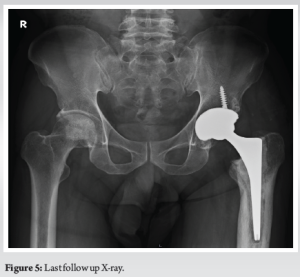

The patient, a 64-year-old male, had been leading a normal life until 15 years ago when he began experiencing left hip pain and difficulty walking. Over the following year, these issues worsened, impending his daily activities. He had a history of chronic smoking and was undergoing steroid treatment for psoriasis. Upon clinical and radiological evaluation, he was diagnosed with avascular necrosis of the left hip leading to secondary osteoarthritis. He underwent uncemented MoM THA (Corail stem with Pinnacle Cementless Acetabular cup, Metal head and Metal liner – DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana) (Fig. 1). For 15 years, he was happy with his surgery. 15 years following his index surgery, he returned with complaints of painful left hip and limping persisting for 3 months. Radiography revealed femoral stem loosening, (Fig. 2) prompting further investigation including metal artefact reduction sequences (MARS) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out pseudotumors, which came back negative, but revealed features of synovial fluid collections around the implant site and features suggestive of aseptic loosening of the hip implant. Although his inflammatory markers were normal, his cobalt and chromium levels were 6.25 (normal range 0.01–0.91) and 5.85 mcg/L (normal range 0.70–28) indicating high cobalt levels and he underwent revision THR with the suspected cause being aseptic stem loosening due to a MoM reaction. During the procedure, we encountered dark brown synovial fluid, indicating potential metallosis, and tissue deposition around the proximal femur and intramedullary canal, which were biopsied for analysis. Biopsy report revealed pigment deposition, pigment laden macrophages and areas of necrosis consistent with metallosis (Fig. 3). The explanted Corail stem demonstrated the absence of its HA coating, which was associated with the presence of a MoM bearing (Fig. 4). He underwent a revision THR. Clinically at 1 year, he is asymptomatic and back to his day today activities(Fig 5).

Case 2

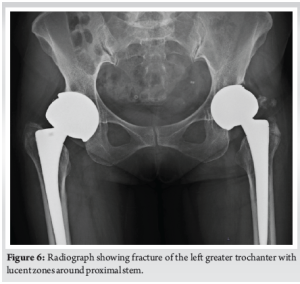

A 63-year-old female who presented to our outpatient department with complaints of bilateral hip pain, more pronounced on the left side, accompanied by a limp for the past 3 months. The patient had undergone bilateral MOM THRs 15 years ago (VerSys Fiber Metal tapered femoral stem with Metasul Component- Metal on Metal articulation, Zimmer Biomet, USA) due to secondary osteoarthritis, and had experienced an uneventful post-operative course until the recent onset of symptoms. On clinical evaluation and radiographic imaging, a fracture of the left greater trochanter was identified, along with lucent zones in both femurs (Fig. 6). Laboratory tests ruled out infection, and MARS MRI revealed features suggestive of metal on metal pseudotumor which confirmed the presence of metallosis. Elevated serum cobalt and chromium levels of 227 mcg/L (normal range 0.01–0.91) and 104 mcg/L (normal range 0.70–28) further supported the diagnosis.

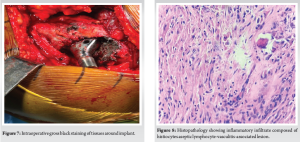

Following comprehensive pre-operative assessment, the patient was scheduled for revision THR on the left side. Intraoperatively, we encountered dark brown synovial fluid, gross black staining of tissues consistent with metallosis, similar to a previous case (Fig. 7). Synovial fluid and tissue samples were sent for histopathological examination, which revealed an aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vasculitis-associated lesion (ALVAL) reaction (Fig. 8). The femoral and acetabular components were revised with ceramic-on-polyethylene implants(Fig 9).

Approximately one out of every eight metal-on metal (MoM) THRs necessitate a revision within a decade, with roughly 60% attributed to complications stemming from arthroplasty wear [9]. Despite advancements in bearing technology, aseptic loosening persists as a primary reason for undergoing revision hip arthroplasty [10]. Metallosis is when metal exposure induces synovitis, causing abnormal dark staining of soft tissues, which can lead to issues such as loosening, tissue necrosis, and excessive fibrosis due to metal corrosion and wear. The absorption of metal debris by macrophages through phagocytosis is a critical mechanism through which implants can instigate inflammatory reactions, ultimately resulting in metallosis [11]. Once macrophages recognize particles, they initiate a sequence of responses that produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, interleukin-18, and tumor necrosis factor-α, along with chemokines such as CXCL8, CCL2, and CCL3, as well as other inflammatory markers. This local inflammation often leads to intense pain, potentially accompanied by tissue or bone death. Moreover, the accumulation of fluid and tissue around the joint, known as pseudotumors, can develop, resulting in a soft tissue lesion [12]. The metal debris released from the implant can also elevate metal-ion levels in the blood, deposit in tissues, and trigger a harmful local tissue response diagnosed as an adverse reaction to metal debris, which encompasses various conditions such as metallosis, ALVAL, and pseudotumors [12]. In MoM hip implants, movement can cause the release of metal ions and particles from the rubbing of the metal components [13]. These particles, especially cobalt and chromium, can have both local and systemic effects. Locally, they cause inflammatory response in the tissues surrounding the implant, altering cytokine expression and causing tissue damage and bone deterioration. While pseudotumor are usually symptomatic and histological analysis often reveals aseptic ALVAL. ALVAL is distinguished by the infiltration of lymphocytes into the tissues adjacent to the implant, contributing to pain, inflammation, and the formation of pseudotumors, often accompanied by a dense perivascular inflammatory infiltrate observable on histopathological examination, serving as a hallmark of ALVAL. This histological confirmation is crucial for diagnosing ALVAL, which is believed to represent a cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction, specifically a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction [14]. Davies et al. further elaborated on this distinct perivascular lymphocytic inflammation within the synovium [15]. Notably, this response deviates from the typical reaction seen in polyethylene devices, which involves a macrophage-driven response to polyethylene debris resulting in osteolysis. In addition to local reactions, elevated systemic metal ion levels have been linked to reduced osseointegration of the femoral stem. Metal ions can also directly interfere with HA by replacing calcium in the HA crystals, which disrupts the mineralization process [16]. Gascoyne et al. noticed a connection between the extent of taper corrosion and the likelihood of aseptic loosening. They proposed that corrosion byproducts might activate macrophages, leading to osteolysis, or that metal particles could trigger lymphocytes to release cytokines. This process could cause osteoclastic bone resorption, which would lead to the breakdown of the proximal HA coating [7]. Consequently, this would result in increasing radiolucencies and eventual loosening of the implant. Metallosis typically lacks distinct clinical signs or symptoms, thus making a comprehensive evaluation of symptoms and physical examination crucial for diagnosis. Our patients presented with limping and hip pain despite having a well- functioning THA in place for over 15 years. The threshold for elevated cobalt levels in the blood indicative of hyper-cobaltemia is typically above 1 μg/L, with patients having MoM implants often showing average blood cobalt levels of 2 μg/L, which may exceed 3 μg/L in cases of bilateral hip arthroplasty [17]. Bolognesi and Ledford suggested a cut off of 7 parts per billion for cobalt or chromium ions as a guideline for treatment decisions [2]. “Both the patients’ cobalt and chromium values were found to be 6.29 mcg/L and 5.87 mcg/L, respectively, for the first patient, and 226.84 mcg/L and 104.38 mcg/L respectively for the second patient”. MARS MRI for the first patient revealed features suggestive of aseptic loosening of the femoral stem and synovial fluid collections around the implant site. In the second patient, the MARS MRI report indicated features suggestive of MoM pseudotumor (left>right). Intraoperative biopsy samples revealed pigment deposition, pigment laden macrophages and areas of necrosis which are consistent with metallosis. In addition to this second case’s biopsy samples revealed an ALVAL reaction.

Our case reports showed that aseptic loosening after THA was likely caused by metallosis resulting from a MoM bearing. Early detection and prompt intervention are crucial in managing metallosis to prevent further complications. Revision THA by replacing bearing surfaces is commonly practiced for addressing these problems and improving long-term outcomes of patients. This study has demonstrated a high risk of loosening of previously osseointegrated femoral stems when paired with a MoM bearing. The loosening mechanism appears to be progressive and associated with the MoM bearing, possibly interacting with the HA coating, even in the in stems lacking HA coating. Both hips functioned well for over 15 years before the onset of loosening and other symptoms. All MoM THA need regular long-term follow-up to closely watch for implant loosening.

This report highlights long-term complications of MoM THA, particularly progressive aseptic loosening due to metallosis. It emphasizes the importance of early detection through imaging (MARS MRI) and elevated metal ion levels, and details successful revision strategies. The findings underscore material compatibility issues, including interactions between MoM bearings and HA coatings, which may accelerate implant loosening. This case reports contributes valuable insights into managing late-onset complications, guiding implant selection, and improving follow-up protocols. The thorough analysis of complications, diagnostic methods, and successful treatments makes this case report a meaningful contribution to orthopedic research.

References

- 1.Girard J, Bocquet D, Autissier G, Fouilleron N, Fron D, Migaud H. Metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in patients thirty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:2419-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Bolognesi MP, Ledford CK. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: Patient evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;23:724-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Bozic KJ, Browne J, Dangles CJ, Manner PA, Yates Adolph J Jr., Weber KL, et al. Modern metal-on-metal hip implants. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:402-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Desai BR, Sumarriva GE, Chimento GF. Pseudotumor recurrence in a post-revision total hip arthroplasty with stem neck modularity: A case report. World J Orthop 2020;11:116-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Raju S, Chinnakkannu K, Puttaswamy MK, Phillips MJ. Trunnion corrosion in metal-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty: A case series. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2017;25:133-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Elias JJ, Nagao M, Chu YH, Carbone JJ, Lennox DW, Chao EY. Medial cortex strain distribution during noncemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;370:250-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Gascoyne T, Flynn B, Turgeon T, Burnell C. Mid-term progressive loosening of hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stems paired with a metal-on-metal bearing. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:225. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Thilak J, Madanan A. Midterm follow-up study of metal on metal total hip replacement. Int J Orthop Sci 2018;4:810-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Bradberry SM, Wilkinson JM, Ferner RE. Systemic toxicity related to metal hip prostheses. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52:837-47. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Bennett D, Delanois RE, Saleh KJ, Thongtrangan I, et al. Total hip arthroplasties: What are the reasons for revision? Int Orthop 2008;32:597-604. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Yang S, Zhang K, Jiang J, James B, Yang SY. Particulate and ion forms of cobalt-chromium challenged preosteoblasts promote osteoclastogenesis and osteolysis in a murine model of prosthesis failure. J Biomed Mater Res Part A 2019;107:187-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Salem KH, Lindner N, Tingart M, Elmoghazy AD. Severe metallosis-related osteolysis as a cause of failure after total knee replacement. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:165-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Agarwal N, To K, Khan W. Cost effectiveness analyses of total hip arthroplasty for hip osteoarthritis: A PRISMA systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 2020;75:e13806. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Koster G, et al. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:28-36. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Davies AP, Willert HG, Campbell PA, Learmonth ID, Case CP. An unusual lymphocytic perivascular infiltration in tissues around contemporary metal-on-metal joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:18-27. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Mabilleau G, Filmon R, Petrov PK, Baslé MF, Sabokbar A, Chappard D. Cobalt, chromium and nickel affect hydroxyapatite crystal growth in vitro. Acta Biomater 2010;6:1555-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Gessner BD, Steck T, Woelber E, Tower SS. A systematic review of systemic cobaltism after wear or corrosion of chrome-cobalt hip implants. J Patient Saf 2019;15:97-104. [Google Scholar | PubMed]