UKA is an effective, bone-preserving option for isolated compartment knee osteoarthritis, with outcomes that can be optimized through proper patient selection, modern implant designs, and advances such as cementless fixation and robotic-assisted techniques.

Dr. Amyn M Rajani, OAKS Clinic, 707, Panchshil Plaza, N S Patkar Marg, Opposite Ghanasingh Fine Jewels, Next to Dharam Palace, Gamdevi, Mumbai - 400 007, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dramrajani@gmail.com

Abstract Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) has emerged as a reliable, bone-preserving option for patients with isolated compartment knee osteoarthritis (OA). Initially limited by poor early outcomes and narrow indications, advances in implant design, patient selection, and surgical technique have led to a resurgence in its use. Contemporary diagnostics rely on precise clinical and imaging assessments to confirm unicompartmental disease while ruling out contraindications. Importantly, traditional exclusion criteria, such as age under 60, high body mass index, patellofemoral OA, anterior cruciate ligament deficiency, and chondrocalcinosis, are being re-evaluated in light of newer evidence, suggesting they are not absolute barriers in all patients. Operative options now include cemented and cementless fixation, fixed- and mobile-bearing designs, and all-polyethylene versus metal-backed components, each with specific advantages and limitations. Robotic-assisted techniques offer improved alignment accuracy and reproducibility compared to conventional manual approaches, potentially enhancing survivorship, although cost and learning curve remain considerations. Post-operative protocols support early mobilization and weight-bearing, facilitating faster recovery than total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Return to sports activity is generally higher after UKA, meeting the expectations of increasingly active patient populations. Surgeon-related factors, particularly experience and case volume, significantly influence outcomes, underscoring the importance of appropriate training and patient selection. As the understanding of UKA indications and techniques continues to evolve, it offers a compelling, less invasive alternative to TKA for well-selected patients. This editorial review highlights current best practices, emerging evidence, and ongoing challenges in optimizing outcomes for UKA.

Keywords: Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, knee osteoarthritis, surgical technique, patient selection, robotic-assisted surgery.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common musculoskeletal disorders globally, and it represents a major source of disability. It limits daily activities, contributes to work-related disability, lowers quality of life, and imposes significant costs on health-care systems [1,2]. When non-surgical management fails to provide adequate relief, surgical options such as partial or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are considered. Both procedures are routinely performed in high-income countries, with demand projected to rise substantially in the coming years [2,3]. In recent years, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) has attracted increasing attention. Evidence suggests UKA offers several advantages over TKA, including a less invasive approach, shorter operative time, greater post-operative range of motion, superior pain relief, faster return to daily activities and sports, and lower overall costs [4,5]. National registry data indicate that UKA utilization has been steadily rising over the past decade, with usage rates in 2014 reported at approximately 5–11% worldwide [6-9]. This review aims to explore key aspects of UKA, highlighting current best practices, emerging evidence, and ongoing challenges in optimizing outcomes for UKA.

The concept of replacing only one knee compartment originated in the 1950s with McKeever and MacIntosh’s metallic tibial plateau [10]. In 1972, Marmor advanced the idea by resurfacing both femoral and tibial components within a single compartment [11]. Despite theoretical advantages, early results were poor, with over 30% requiring revision within 10 years due to issues such as tibial loosening and polyethylene wear [12,13]. By the mid-1970s, high failure rates and complications such as poor alignment correction and patellofemoral OA (PFOA) led to declining use [14]. A turning point came in 1989 when Kozinn and Scott proposed strict selection criteria, improving outcomes [15]. Subsequent studies reported 10-year survival rates of 97–98% with refined implants such as the Miller–Galante and Oxford mobile-bearing designs [16]. Minimally invasive techniques were introduced to reduce tissue damage, though results have varied [17]. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a better understanding of biomechanics, improved implant designs, and clearer patient selection criteria paved the way for the modern resurgence and wider acceptance of UKA [18].

Diagnostics

Careful clinical and radiographic evaluation remains essential for diagnosing knee OA and selecting appropriate candidates for UKA. History, physical examination, and imaging together ensure precise identification of isolated medial or lateral compartment disease, guiding surgical decision-making.

Physical examination

Key aspects of the examination include localization of pain (medial or lateral joint line), assessment of range of motion, limb alignment, ligament stability (including anterior cruciate ligament [ACL] integrity through Lachman or anterior drawer tests), and evaluation for patellofemoral discomfort. Varus and valgus stress tests help assess collateral ligaments and the correctability of deformity. Pain confined to one compartment is a basic requirement for UKA candidacy.

Radiographic assessment

Standard imaging includes weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral knee radiographs. Additional views, such as the Rosenberg (45° flexion posteroanterior) view, improve sensitivity for detecting unicompartmental disease. Merchant views evaluate the patellofemoral joint. Alignment radiographs can reveal deformity and joint space preservation in the contralateral compartment. Stress radiographs help assess deformity, correctability, and ligament integrity. Magnetic resonance imaging is increasingly used to detect early degenerative changes in the opposite compartment, offering superior assessment of cartilage, subchondral bone, ligaments, and menisci.

Indications and contraindications

Historically, Kozinn and Scott’s criteria [15] for UKA were strict, including age over 60, low body weight (<82 kg), low activity demands, minimal deformity (<15°), and correctable alignment. While these criteria improved outcomes at the time, advances in implant design and surgical technique have led to broader indications.

Age

Historically, being under 60 years old was viewed as a relative contraindication for UKA due to concerns about increased polyethylene wear in more active patients. However, more recent studies, including those from the Oxford Group, have challenged this assumption. They found comparable 10-year survival rates in younger patients (around 97%) to those seen in patients over 60 (approximately 95%) [19,20]. The anticipated risk of early implant wear in younger, more active individuals has not been supported by evidence. In fact, these patients often achieve even better functional outcomes. This may be because their higher activity levels and demands align well with the advantages of UKA, such as faster recovery and greater post-operative range of motion.

Body mass index (BMI)

Obesity has traditionally been viewed as a relative contraindication due to the risks of implant loosening and wear. Yet large series have found no significant difference in survival rates across BMI categories, supporting UKA use even in patients with higher BMI [21,22].

PFOA

Originally considered a contraindication, PFOA has been re-evaluated. Multiple studies, including large series, have found no association between pre-operative PFOA and worse UKA outcomes. Improvements in alignment with UKA may even reduce patellofemoral contact forces [23,24].

ACL

ACL deficiency was historically seen as a contraindication due to concerns over instability and loosening. Current evidence suggests that, in selected patients, UKA combined with ACL reconstruction can yield good results. In older, less active patients, UKA alone may still be an option with careful selection and a fixed bearing implant [25,26].

Chondrocalcinosis

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease has been viewed with caution due to concerns over accelerated OA in the contralateral compartment. However, studies have not confirmed higher progression rates or reduced implant survival, and functional outcomes remain favorable [27,28]. Modern evidence suggests that many of the original strict contraindications for UKA – including age under 60, higher BMI, PFOA, chondrocalcinosis, and even ACL deficiency – are not absolute. Careful patient selection, thorough diagnostic work-up, and refined surgical technique have expanded UKA eligibility, supporting its role as a viable, bone-preserving option for isolated compartment knee OA.

UKA is most commonly performed on the medial tibiofemoral compartment, accounting for around 90% of cases. Variations in technique include choices between cemented and cementless fixation, fixed- or mobile-bearing designs, metal-backed or all-polyethylene components, and conventional versus robotic-assisted implantation.

Cemented versus cementless fixation

Cemented fixation has long been the standard in UKA, offering reliable outcomes and high survivorship [29]. Recent Indian data confirm these advantages, with Rajani et al. reporting a 96.85% 5-year survivorship and significant functional gains, including improved range of motion and the ability to squat and sit cross-legged, highlighting the procedure’s suitability for cultural needs and underlining the importance of surgeon training to ensure success [30]. However, its main limitation is aseptic loosening, often linked to cementation errors, thermal damage, or fibrous tissue formation at the interface. To address these issues, interest in cementless designs has grown [31]. Modern cementless implants use porous titanium and hydroxyapatite coatings to promote bone ingrowth or ongrowth, achieving stable, press-fit fixation [32]. The Oxford UKA is now a widely used cementless option. While cementless techniques reduce risks such as radiolucent lines and eliminate cementation errors, they require greater impaction, raising concerns about periprosthetic fractures, especially in older women with osteoporosis. Recent studies and systematic reviews suggest cementless UKA provides comparable mid-term outcomes with advantages such as shorter surgical time and reliable fixation, though longer-term evidence is still needed to confirm its lasting benefits [32,33].

Fixed-bearing versus mobile-bearing designs

Early fixed-bearing UKAs had higher point loading, increasing polyethylene wear and loosening risk. Mobile-bearing designs, such as the Oxford implant, aim to reduce these stresses with congruent articulation and better load distribution [34]. However, mobile bearings require precise ligament balancing to avoid dislocation, particularly in the more lax knees. Modifications such as domed lateral designs have improved outcomes, achieving survival rates exceeding 90% at 4-year follow-up. Registry and comparative studies generally find no clear long-term survival advantage between fixed- and mobile-bearing designs, with both showing similar reasons for revision, such as OA progression and loosening [35,36].

All-polyethylene versus metal-backed components

Two main tibial component designs exist: all-polyethylene (inlay) and metal-backed (onlay). All-polyethylene implants conserve more bone but rely on subchondral support. Metal-backed designs offer improved load distribution and allow cementless fixation but require a deeper tibial cut. Both are used in current practice, with metal-backed components favored for cementless approaches.

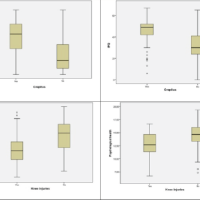

Conventional versus robotic-assisted techniques

Traditional UKA uses manual guides to achieve alignment and balance, with registry data indicating survivorship around 91–92% at 10 years [37]. Accurate implant positioning is crucial for longevity. Advances such as computer navigation and robotic assistance aim to improve precision, component alignment, and soft-tissue balance. Robotic systems provide real-time feedback and have demonstrated superior alignment accuracy compared to conventional methods. Early studies suggest potential improvements in short-term outcomes and survivorship. However, costs, the need for pin placement, and limited long-term data remain concerns.

Post-operative care and rehabilitation

Rehabilitation protocols for UKA typically allow immediate full weight-bearing, with patients often experiencing faster recovery than after TKA. Enhanced pain management and rapid recovery protocols enable earlier mobilization, reducing risks of complications such as DVT and infections. Early discharge and home recovery further improve patient comfort and outcomes.

Return to sports

Patient expectations for activity after UKA are high. Studies show higher return-to-sport rates for UKA than TKA, with 93% returning to low-impact sports and significant participation even in intermediate- and some high-impact activities. Return typically occurs around 12 weeks postoperatively, with UKA patients more likely to maintain or increase pre-operative activity levels compared to TKA recipients.

Surgeon-related considerations

Both technical and non-technical skills play a crucial role in the success of UKA. Evidence shows that surgeons with higher case volumes tend to achieve better outcomes and have fewer complications. This relationship is even more pronounced for UKA compared to TKA, with low-volume surgeons experiencing significantly higher revision rates. Patient selection and adherence to clear indications are equally important. Surgeons who perform UKA in more than 20% of their knee arthroplasties tend to have lower revision rates, with optimal results seen when UKA comprises around half of their knee replacements. Meta-analyses suggest that the proportion of UKA within a surgeon’s practice is more predictive of outcomes than overall caseload alone [38]. A major barrier to the wider adoption of UKA is many surgeons’ reluctance to offer it, often due to limited training or lack of exposure during their education. This gap can be addressed through dedicated training programs, courses, and fellowships under experienced surgeons who routinely perform high-quality UKA, ensuring new practitioners develop the skills and confidence needed to deliver reliable outcomes.

Given the strong mid-term results and advantages of cementless UKA – such as reliable fixation and faster recovery – it is expected that cementless designs will see wider adoption, with more manufacturers likely to expand their offerings. At present, UKA accounts for roughly 8–11% of knee replacements, but studies suggest many more patients could be appropriate candidates. Improving awareness among surgeons about its role in isolated compartment OA could help increase its use. Meanwhile, robotic-assisted techniques are poised to further transform UKA by enhancing surgical precision, customization, and consistency. Future developments may streamline planning and execution, reduce the learning curve, and integrate advanced features such as real-time sensing and image-free kinematic planning. Such innovations aim to better reproduce natural joint mechanics while simplifying workflows, potentially broadening access to high-quality UKA and improving outcomes for a larger patient population.

UKA has evolved from a procedure with limited indications and variable early results into a well-established, evidence-based option for managing isolated compartment knee OA. Advances in implant design, fixation, and robotic-assisted techniques have improved surgical precision and mid-term outcomes. Broader patient selection criteria, supported by robust contemporary evidence, now challenge traditional contraindications such as younger age, higher BMI, patellofemoral disease, and ACL deficiency. Nevertheless, success with UKA depends critically on careful patient evaluation, meticulous surgical technique, and the surgeon’s experience. As expectations rise for faster recovery and higher functional demands, UKA offers an attractive, bone-preserving alternative to total knee arthroplasty.

UKA is a reliable, bone-preserving option for isolated compartment osteoarthritis, with expanded indications supported by contemporary evidence. Optimal outcomes depend on careful patient selection, surgeon experience, and adoption of modern techniques such as fixation and robotic assistance.

References

- 1.Bindawas SM, Vennu V, Auais M. Health-related quality of life in older adults with bilateral knee pain and back pain: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:2095-101. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Hooper G, Lee AJ, Rothwell A, Frampton C. Current trends and projections in the utilisation rates of hip and knee replacement in New Zealand from 2001 to 2026. N Z Med J 2014;127:82-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Jt Surg Am 2007;89:780-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Amin AK, Patton JT, Cook RE, Gaston M, Brenkel IJ. Unicompartmental or total knee arthroplasty? Results from a matched study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;451:101-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Lyons MC, MacDonald SJ, Somerville LE, Naudie DD, McCalden RW. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty database analysis: Is there a winner? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:84-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.American Joint Replacement Registry. American Joint Replacement Registry-Annual Report 2014; 2014. Available from: https://www.ajrr.net/images/annual_reports/ajrr_2014_annual_report_final_11-11-15.pdf. Last accessed June 2025. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Registry. Hip and knee Arthroplasty Annual Report 2015; 2015. Available from: https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/217745/hip/and/knee/arthroplasty Last accessed June 2025. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland. 12th Annual report 2015; 2015. Available from: https://www.njrreports.org.uk/portals/0/pdfdownloads/njr12thannualreport2015.pdf Last accessed June 2025. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.New Zealand Joint Registry. The New Zealand Registry Annual Report; 2014. Available from: https://nzoa.org.nz/system/files/web_dh7657_nzjr2014report_v4_12nov15.pdf Last accessed June 2025. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.McKeever DC. The choice of prosthetic materials and evaluation of results. Clin Orthop 1955;6:17-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Marmor L. The modular knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1973;94:242-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Marmor L. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Ten- to 13-year follow up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;226:14-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Lindstrand A, Stenstrom A, Lewold S. Multicenter study of unicompartmental knee revision. PCA, Marmor, and St Georg compared in 3,777 cases of arthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand 1992;63:256-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Insall J, Aglietti P. A five to seven-year follow-up of unicondylar arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;62:1329-37. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Kozinn SC, Scott R. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989;71:145-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Berger RA, Nedeff DD, Barden RM, Sheinkop MM, Jacobs JJ, Rosenberg AG. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clinical experience at 6- to 10-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;87-A:50-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Repicci JA. Total knee or uni? Benefits and limitations of the unicondylar knee prosthesis. Orthopedics 2003;26:274. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill HS, Barker K, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Minimally invasive Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee replacement: Results of 1000 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:198-204. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill HS, Smith G, Price AJ, Dodd CA, et al. Unnecessary contraindications for mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:622-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Van der List JP, Chawla H, Zuiderbaan HA, Pearle AD. The role of preoperative patient characteristics on outcomes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis critique. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2617-27. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Murray DW, Pandit H, Weston-Simons JS, Jenkins C, Gill HS, Lombardi AV, et al. Does body mass index affect the outcome of unicompartmental knee replacement? Knee 2013;20:461-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Plate JF, Augart MA, Seyler TM, Bracey DN, Hoggard A, Akbar M, et al. Obesity has no effect on outcomes following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;25:645-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Goodfellow JW, O’Connor J. Clinical results of the Oxford knee. Surface arthroplasty of the tibiofemoral joint with a meniscal bearing prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;205:21-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Beard DJ, Pandit H, Gill HS, Hollinghurst D, Dodd CA, Murray DW. The influence of the presence and severity of pre-existing patellofemoral degenerative changes on the outcome of the Oxford medial unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:1597-601. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Posterior slope of the tibial implant and the outcome of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:506-11. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Goodfellow JW, Kershaw CJ, Benson MK, O’Connor JJ. The Oxford Knee for unicompartmental osteoarthritis. The first 103 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:692-701. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Hernigou P, Pascale W, Pascale V, Homma Y, Poignard A. Does primary or secondary chondrocalcinosis influence long-term survivorship of unicompartmental arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:1973-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 28.Kumar V, Pandit HG, Liddle AD, Borror W, Jenkins C, Mellon SJ, et al. Comparison of outcomes after UKA in patients with and without chondrocalcinosis: A matched cohort study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;25:319-24. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 29.Bert JM. 10-year survivorship of metal-backed, unicompartmental arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1998;13:901-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 30.Rajani AM, Mittal AR, Shah UA, Kulkarni VU, Dubey R. Midterm functional outcomes and survivorship of Oxford cemented medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A comprehensive analysis of the Indian scenario. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2025;68:103115. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 31.Yoshida K, Tada M, Yoshida H, Takei S, Fukuoka S, Nakamura H. Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in Japan--clinical results in greater than one thousand cases over ten years. J Arthroplasty 2013;28 9 Suppl:168-71. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 32.Pandit H, Jenkins C, Beard DJ, Gallagher J, Price AJ, Dodd C, et al. Cementless Oxford unicompartmental knee replacement shows reduced radiolucency at one year. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:185-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 33.Kendrick BJL, James AR, Pandit H, Gill HS, Price AJ, Blunn GW, et al. Histology of the bone-cement interface in retrieved Oxford unicompartmental knee replacements. Knee 2012;19:918-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 34.Kannan A, Lewis PL, Dyer C, Jiranek WA, McMahon S. Do fixed or mobile bearing implants have better survivorship in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty? A study from the Australian orthopaedic association national joint replacement registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2021;479:1548-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 35.Migliorini F, Bosco F, Schäfer L, Cocconi F, Kämmer D, Bell A, et al. Revision of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:985. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 36.Albishi W, AbuDujain NM, Aldhahri M, Alzeer M. Unicompartmental knee replacement: Controversies and technical considerations. Arthroplasty 2024;6:21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 37.Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Alignment influences wear in the knee after medial unicompartmental arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;423:161-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 38.Hamilton TW, Rizkalla JM, Kontochristos L, Marks BE, Mellon SJ, Dodd CA, et al. The interaction of caseload and usage in determining outcomes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:3228-37.e2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]