This article describes a novel technique of simultaneous ACL and MCL reconstruction by modifying the Lind technique which provides a stable fixation of grafts in cases with high BMI.

Dr. Rajkumar S Amaravathi,Professor Department of Orthopedics, Head Division of Arthroscopy, Sports Injury,Joint Preservation,& Regenerative Medicine St John’s Medical College & Hospital Bangalore 560034 India. E-mail: rajkumar_as@yahoo.co.in

Introduction: Multiligamentous knee injury (MLKI) is a difficult and devastating injury of the knee defined as tear/disruption (involving grade III) of at least 2 of the 4 major ligaments of the knee. Combined anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries are the most common type of MLKI. MCL injuries are concurrent in 20–38% of ACL injuries and are common in sports activities that involve pivoting of the knee joint, forced hyperextension, and rapid deceleration. Many techniques have been described for superficial MCL (sMCL) reconstruction, with single-bundle and double-bundle techniques used for the associated posterior oblique ligament (POL) using both allografts and autografts. Among these, one of the most common techniques with a good outcome (keeping the semitendinosus tibial attachment intact) was described by Lind et al. Our technique for sMCL and POL reconstruction is a modification of the Lind technique. In this technique, the semitendinosus with its intact tibial attachment is rerouted anatomically in the tibial tunnel with an adjustable loop, and on the femoral side, an adjustable loop UltraButton is used with a 2-incision technique. The remaining graft is reattached to the posteromedial tibia as POL using an interference screw

Material and Methods: We treated patients with chronic ACL injuries combined with grade III valgus laxity. A total of 5 patients met the inclusion criteria of the study, and there were no patients lost to follow-up. The mean age was 26.5 years with a standard deviation of 4.05 years. All surgeries were performed by a single experienced author, Dr RK, at our institution between September 2023 and May 2024. The mean time from injury to surgery was 2.5 months, and the duration of follow-up was 6 months. 3 patients were female and 2 were male patients.

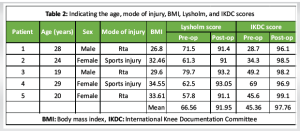

Results: Out of 5 patients who were treated, 2 were in the age group of 15–20 years and 3 were 20–30 years. 2 were male patients and 3 were females. Road traffic accidents accounted for 66% (3 cases) of the total cases as the most common mechanism of injury followed by sports injuries (34%, 2 cases). All 5 patients operated on with simultaneous ACL and MCL reconstruction (modified Lind technique) had excellent results based on the Lysholm scoring system. Comparative analysis was done between pre-surgery and post-surgery Lysholm scores and we found that there was a statistically significant difference between them with P < 0.001. A significant improvement in the International Knee Documentation Committee subjective score was detected at follow-up.

Conclusion: In patients with high body mass index >25 kg/m2, chronic ACL-MCL (grade III) injuries, simultaneous ACL-MCL reconstruction with the modified Lind technique improves anterior, valgus, and rotatory stability of the knee and produces a good functional result.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, superficial medial collateral ligament, multiligamentous knee injury, medial collateral ligament, posterior oblique ligament.

Multiligamentous knee injury (MLKI) is a difficult and devastating injury of the knee defined as tear/disruption (involving grade III) of at least 2 of the 4 major ligaments of the knee [1]. With an increase in the number of people engaging in sports activities and with an increase in high velocity road traffic accidents (RTA), the incidence of MLKI is on the rise. Combined anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries are the most common type of MLKI [2]. MCL injuries are concurrent in 20–38% of ACL injuries and are common in sports activities that involve pivoting of the knee joint, forced hyperextension, and rapid deceleration [3]. Medial instability is quantified from Grade I to III. A grade I injury has microscopic tearing with no instability or joint widening. Grade II injuries are partial tears with 5–10 mm of joint widening and no instability. Grade III lesions have >10 mm of joint opening with instability [4]. The ACL comprises two bundles: Anteromedial and posterolateral. The anteromedial bundle restricts anterior tibial translation; the posterolateral bundle contributes to rotatory stability [5]. The MCL is composed of superficial and deep components. The superficial MCL (sMCL) is the primary restraint to valgus stress with the posteromedial capsule, including the posterior oblique ligament (POL), contributing in full extension, where it also controls internal rotation [6]. The deep portion is a major secondary restraint to anterior tibial translation and provides minor static stabilization against valgus stress [7]. Deep MCL and sMCL have a synergistic role in restraining external rotation of the tibia. The World Health Organization classified the body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 30 kg/m2 as overweight, more than 30 kg/m2 as obesity and more than 40 kg/m2 as morbid obesity [8]. High BMI levels increase the compression forces on the knee joint, increasing the cartilage and meniscus injury risk in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction (ACLR)/MCLR. Hence, BMI is one of the important predictors of the outcomes of ACLR and MCL reconstruction [9]. Higher BMI levels adversely affect quadriceps and hamstring strength recovery, hop performance, dynamic balance, and self-reported knee function in patients who have undergone ACLR. High BMI individuals have a higher post-operative complication rate, greater incidence of surgical revision, and reinjury of ACL. The choice of graft and technique of reconstruction of ACL and MCL is important to prevent failure, and there is no single graft and technique that ticks all the boxes [9]. Treatment of combined ACL-MCL injuries in these individuals remains controversial, with a variety of surgical and conservative management options. In general, conservative management is reserved for grade I and II MCL injuries, while ACLR is usually recommended if the ACL is torn. Successful outcomes from grade III MCL treatment, with return to high-level sporting activities, are shown from surgical management. Many techniques have been described for sMCL reconstruction, with single-bundle and double-bundle techniques used for the associated POL using both allografts and autografts [10]. Among these, one of the most common techniques with a good outcome (keeping the semitendinosus tibial attachment intact) was described by Lind et al. [11]. Our technique for sMCL and POL reconstruction is a modification of the Lind technique. In this technique, the semitendinosus with its intact tibial attachment is rerouted anatomically in the tibial tunnel with an adjustable loop, and on the femoral side, an adjustable loop UltraButton is used with a 2-incision technique. The remaining graft is reattached to the posteromedial tibia as POL using an interference screw.

Patients

We treated patients with chronic ACL injuries combined with grade III valgus laxity.

The inclusion criteria for this case series were (1) combined ACL-MCL injury, (2) BMI >25 kg/m2, and (3) subjective medial instability with a chronic III MCL injury (medial joint opening >10 mm based on radiographs compared with the contralateral knee) for more than 6 weeks.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

(1) Diagnosis of a MLKI (such as a posterior cruciate ligament injury or posterolateral corner injury), (2) BMI <25 kg/m2 (3) active infection (septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or soft tissue infection), (4) malalignment of lower limb, and (5) any previous surgery on the affected knee.

A total of 5 patients met the inclusion criteria of the study, and there were no patients lost to follow-up. The mean age was 26.5 years. All surgeries were performed by a single experienced author, Dr RK, at our institution between September 2023 and May 2024. The mean time from injury to surgery was 2.5 months, and the duration of follow-up was 6 months. Three patients were female and 2 were male.

Case 1

A 28-year-old male was involved in a high-energy RTA resulting in combined ACL and MCL disruption. His BMI was 26.8 kg/m2, placing him in the overweight category. He underwent simultaneous reconstruction of both ligaments using the Modified Lind Technique. At the final follow-up, the Lysholm score was 91.4, and the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score was 96.1 – demonstrating a significant gain in knee stability and function.

Case 2

A 24-year-old female sustained combined ACL and MCL injuries during a pivoting sports incident. She had a BMI of 32.46 kg/m2, in the obese range. The dual-ligament reconstruction led to remarkable recovery, with post-operative scores improving to 91.0 (Lysholm) and 98.5 (IKDC). She reported a return to near-normal activity levels with no ligamentous instability.

Case 3

A 19-year-old male, involved in a RTA, presented with ACL and MCL tears. His BMI was 29.6 kg/m2. Baseline Lysholm and IKDC scores were moderately impaired at 79.7 and 49.2, respectively. Following the Modified Lind single-stage reconstruction, his scores elevated to 93.2 and 98.2. Postoperative assessment revealed excellent ligament integrity and restoration of full knee range of motion (ROM).

Case 4

A 29-year-old female injured her knee during athletic sports activity, resulting in ACL and MCL rupture. Her BMI was 34.55 kg/m2 (obese). After undergoing simultaneous reconstruction, she achieved Lysholm and IKDC scores of 93.05 and 96.9, respectively. Her outcome was notable given the BMI-associated risks for ligament healing and rehabilitation.

Case 5

A 20-year-old female sustained a knee injury in an RTA, with combined ACL-MCL damage. Her BMI was 33.61kg/m2. She underwent the modified Lind single-stage procedure, resulting in postoperative scores of 91.1 (Lysholm) and 99.1 (IKDC). She regained full knee function and reported satisfaction with stability and performance.

Surgical technique

Under spinal anesthesia patient is positioned supine with the knee in 90° flexion with foot and lateral supports. Skin marking done (Fig. 1). Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed; ACL tear is confirmed. Now, a valgus stress test was done to intraoperatively check for instability and opening of the medial joint line. Peroneus longus graft harvested from the ipsilateral leg using standard technique (Fig. 2). Graft is prepared and tubularized in a standard fashion. Femoral tunnel and tibial tunnel were prepared using Sironix ACL jig (Healthium Medtech Peenya, Bangalore), and graft was passed and fixed with Infiloop (Healthium Medtech Peenya, Bangalore) on the femoral side and interference screw on the tibia side in 30° flexion and by applying posterior drawer force. An arthroscopic drive-through test (Fig. 3) was done after ACL reconstruction. If it is found to be a grade three injury, MCL reconstruction is done using a hamstring graft by preserving the tibial insertion through an open technique (modified Lind technique).

Our procedure of sMCL and POL reconstruction is a 2-incision technique for exposure of the tibial and femoral anatomic attachment points. It begins with surface marking as shown in (Fig. 1), followed by a 4 cm oblique incision between the tibial tuberosity and the posterior border of the tibia centered over the palpable pes tendons (the same incision which is already used for interference screw fixation of ACL graft in tibia). The semitendinosus tendon is palpated over the sartorius fascia by rolling the index finger over the tendon, and the fascia is incised just above it. The semitendinosus is isolated with mixter forceps, and a loop suture is placed and secured over the graft. The semitendinosus vincula are identified and cut to avoid premature amputation of the graft. The graft is harvested using an open tendon stripper, keeping its insertion on the tibia as described in the Lind technique. The graft is cleaned and prepared. Harvested semitendinosus is tubularized doubling the graft upon itself in a standard fashion. The graft diameter is confirmed. Isometric point (6 cm distal to joint line) for the sMCL on the tibia is identified and drilled using 4.5 mm cannulated drill (Smith and Nephew, Andover). The anteromedial cortex of the tunnel is rounded off to avoid graft abrasion. 15 mm is marked on the graft, which is mounted on an adjustable UltraButton (Smith and Nephew, Andover) (Fig. 4) and is shuttled through the tibial tunnel from medial to lateral side for secure fixation on the proximal tibia. Synching of the adjustable loop is done in such a way that 15 mm of the semitendinosus double looped graft is inside the tunnel.

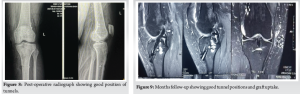

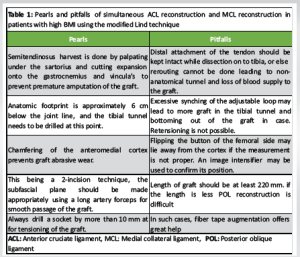

The free end of the remaining semitendinosus is passed in the subfascial plane on the medial side of the tibia. It is looped on itself so that only 2.5 cm of graft can now be fixed in the femoral isometric point for sMCL, posterior and proximal to the medial epicondyle. The remaining free end of the graft is whipstitched with fiber tape (Healthium MedTech Peenya, Bangalore) to be used to recreate POL. The graft is fixed at the isometric point on the femur using an adjustable UltraButton (Smith and Nephew Andover) to create sMCL in a standard fashion (Fig. 5). Knee is maintained at 30° valgus stress during the fixation. The 6 mm diameter POL tunnel is drilled at the isometric point on the posteromedial proximal tibia, 1.5 cm below the joint line, making sure the Acl and pol tunnel do not coalesce. The graft is secured with 7 mm bio screw (Healthium Medtech Peenya, Bangalore) (Fig. 6) with the knee at 0 degrees and valgus stress. Tension in the graft is checked, and Image intensifier is used to cross-verify the fixation. Furthermore, negative drive through on the medial side is visualized. There is room for further tightening of the adjustable button if the fixation is little lax. The line diagram for this technique is as shown in Fig. 7. Wound is closed in layers, and check X-ray is done postoperatively (Fig. 8). Pearls and pitfalls of the technique are tabulated in (Table 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was done after 6 months to check for ligamentization, tunnel widening, and tunnel positions which was found to be satisfactory. The 6-month follow-up MRI images are as in (Fig. 9).

Rehabilitation as per Ohio State University Protocol [12]

The knee was locked with a hinged knee brace at 0–60° flexion during the first 4 post-operative weeks. Early postoperative knee motion was recommended for patients to decrease the risk of post-operative intra-articular adhesion and to minimize the risk of post-operative stiffness of the knee.

Exercises included straight-leg raises, quadriceps strengthening exercises, and calf pumps, which were encouraged beginning at day 1 after surgery.

From 4 to 6 weeks, the patients were allowed 0–90° of ROM. After 6 weeks, the patients were encouraged to reach full ROM.

The patients were advised to bear partial weight while walking during the 2 to 6-week post-operative period. Full weightbearing began 6–8 weeks postoperatively according to each patient’s tolerance.

Evaluation

Patients were evaluated both preoperatively and postoperatively, at 6-month follow-up using IKDC objective scores and Lysholm score.

Out of 5 patients who were treated, 2 were in the age group of 15–20 years and 3 were 20–30 years. 2 were male patients and 3 were females. RTA accounted for 66% (3 cases) of the total cases as the most common mechanism of injury, followed by sports injuries (34%, 2 cases). All 5 patients operated on with simultaneous ACL and MCL reconstruction (modified Lind technique) had excellent results based on the Lysholm scoring system. ACL and MCL stability showed excellent results in all 5 patients (Fig. 10). Comparative analysis was done between pre-surgery and post-surgery Lysholm scores, and we found that there was a statistically significant difference between them with P < 0.001. The mean post-operative Lysholm scores were 91.95 with an SD of 5.593 and a P < 0.001 compared to the mean pre-operative Lysholm score of 66.56. All patients completed the IKDC criteria evaluations, and their pre-operative and final follow-up test results were compared and tabulated in (Table 2). A significant improvement in the IKDC subjective score was detected, as it increased from a pre-operative mean of 45.36 (range, 28.7–69.0) to a mean of 97.76 (range, 95.5–100.0) at the last follow-up. No significant difference was found in the outcomes between genders and side of the injury.

Involvement of both the ACL and MCL represents the most common presenting pattern for MLKIs [1]. The optimal management of combined ACL-MCL injuries lacks a global consensus. Several approaches exist, which can be broadly divided based on surgical intervention for one or both ligaments [13]. Ramakanth et al. reported no difference between MCL suture tape augmentation and non-operative treatment of MCL during ACL reconstruction. More clinical data on the use, indications, outcomes, and complications of suture tape augmentation are still needed [14]. Further uncertainty surrounds the best interval between injury and surgery, as well as the choice of surgical technique. For grade I and II MCL injuries, ACLR alone is often sufficient. For grade III MCL injuries, surgical intervention for medial stability is recommended for a better outcome of reconstructed ACL [15]. Acute injuries (<8 weeks) mandate repair, and chronic (>8 weeks) injuries require reconstruction of MCL. All 5 cases in our series were operated after 8 weeks after injury [16]. After reconstruction of ACL and MCL, our study showed an average post-operative Lysholm score of 91.95, and there was a statistically significant improvement in the functional outcome assessed using Lysholm score with a P < 0.001. 100% (5 cases) of our patients showed excellent results. This is comparable to the findings in the study by Halinen et al. [17] which had 96% of study population with an excellent score. The mean IKDC score in our series was 97.76 which is comparable to another study by Zhang et al. [18]. There has been a growing interest in the use of suture tape augmentation (“internal bracing”) in ligament surgery. There are several concerns regarding its use for MCL surgery, such as fixation location on the tibia and femur, tensioning, and the risks of over-constraining the knee, joint stiffness, and the different biomechanical properties of non-biologic material compared to collagen. LaPrade and Chahla in an expert consensus statement found over 90% agreement that the evidence for polyethylene tape re-enforcement does not support combined acute “Internal Bracing” of the Medial side and ACL reconstruction for the treatment of combined, complete ACL and MCL rupture [19]. For medial reconstruction (MCL along with POL), double-bundle non-anatomic and anatomic techniques are described. Yoshiya et al. used autologous semi-T and/gracilis tendons as free grafts in the anatomic reconstruction of the sMCL. In their series, the graft was fixed proximally with screws and distally with extracortical fixation [20]. LaPrade and Wijdicks used 2 tunnels in the femur and 2 in the tibia for anatomic MCL and POL reconstruction. Although more anatomical, the techniques described previously used interference screw fixation, which led to complications like graft amputation while trying to secure a screw into hard cortical tibial bone. Tunnel coalescence is also a problem in the setting of MLKI [21]. Lind et al. described a technique for combined MCL and POL injuries in which the semitendinosus attachment is kept intact on the tibia, which avoids a potential problem of screws on the tibial side [11]. Furthermore, it is more biological as the blood supply to the graft is preserved. A drawback of their technique is that the semitendinosus is anterior to the MCL, which is non-anatomic and anisometric [22]. Hence, we modified this Lind technique by rerouting the semitendinosus anatomically. Furthermore, our technique uses suspensory fixation, thus avoiding the use of an interference screw on the tibial tunnel and femoral tunnel. Rerouting of the semitendinosus, also described by Joshi et al., uses a weave technique, but it cannot be used in cases of MCL avulsion from the tibia side, and weaving is a less-secure fixation, with chances of soft tissue cut through after mobilization [23]. Our technique is a modification of the Lind technique, but it differs in several ways. In our technique, the semitendinosus graft is rerouted and placed anatomically in the tibial tunnel and fixed with, femoral attachment that is also by adjustable suspensory button fixation which gives the advantage of better healing in the tunnel, fewer hardware problems, and a choice of differential tensioning on both the femur and tibia. Wijdicks et al. have proved that cortical suspensory fixation of soft tissue grafts is superior to interference screw fixation [24]. Watson et al. demonstrated better results with dual adjustable suspensory cortical fixation with better valgus stability because this technique helps to re-tension the graft after fixation, thus improving graft healing [25].

In patients with high BMI >25 kg/m2, chronic ACL-MCL (grade III) injuries, simultaneous ACL-MCL reconstruction with the modified Lind technique improves anterior, valgus, and rotatory stability of the knee and produces a good functional result at a minimum follow-up of 6 months.

Simultaneous ACL and MCL reconstruction using the modified Lind technique is a reliable and effective option in patients with high BMI and chronic grade III MCL injuries, providing excellent anterior, valgus, and rotatory stability. Preserving the semitendinosus tibial attachment with suspensory fixation ensures better graft healing and anatomic reconstruction.

References

- 1. Verma N, Singh H, Mohammad N, Srivastav S. Concomitant multiligamentous knee injury and patellar tendon tear- a rare injury pattern. J Arthrosc Jt Surg 2018;5:183-6. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van der List JP, DiFelice GS. Primary repair of the medial collateral ligament with internal bracing. Arthrosc Tech 2017;6:e933-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ateschrang A, Döbele S, Freude T, Stöckle U, Schröter S, Kraus TM. Acute MCL and ACL injuries: First results of minimal-invasive MCL ligament bracing with combined ACL single-bundle reconstruction. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2016;136:1265-72. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hughston JC, Andrews JR, Cross MJ, Moschi A. Classification of knee ligament instabilities. Part I. The medial compartment and cruciate ligaments. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1976;58:159-72. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elkin JL, Zamora E, Gallo RA. Combined anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament knee injuries: Anatomy, diagnosis, management recommendations, and return to sport. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2019;12:239-44. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robinson J, Fink C, Moatshe G. Grade III MCL management strategies in patients having ACL reconstruction vary depending on injury pattern and patient factors. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2024;41:2033-2036. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andrews K, Lu A, Mckean L, Ebraheim N. Review: Medial collateral ligament injuries. J Orthop 2017;14:550-4. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mall NA, Chalmers PN, Moric M, Tanaka MJ, Cole BJ, Bach BR Jr., et al. Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:2363-70. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kluczynski MA, Marzo JM, Bisson LJ. Factors associated with meniscal tears and chondral lesions in patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:2759-65. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Encinas-Ullán CA, Rodríguez-Merchán EC. Isolated medial collateral ligament tears: An update on management. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3:398-407. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lind M, Jakobsen BW, Lund B, Hansen MS, Abdallah O, Christiansen SE. Anatomical reconstruction of the medial collateral ligament and posteromedial corner of the knee in patients with chronic medial collateral ligament instability. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1116-22. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenkins SM, Guzman A, Gardner BB, Bryant SA, Sol SR, McGahan P, et al. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Review of current literature and recommendations. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2022;15:170. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Papalia R, Osti L, Del Buono A, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Management of combined ACL-MCL tears: A systematic review. Br Med Bull 2010;93:201-15. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramakanth R, Sundararajan SR, Sujith BS, D’Souza T, Arumugam P, Rajasekaran S. Medial collateral ligament repair, isolated suture-tape-bracing and no repair for grade III Medial collateral ligament tears during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction have similar outcome for combined anterior cruciate ligament with medial collateral ligament injury: A 3-arm randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy 2024;41:2021-32. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grant JA, Tannenbaum E, Miller BS, Bedi A. Treatment of combined complete tears of the anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligaments. Arthroscopy 2012;28:110-22. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Razi M, Soufali AP, Ziabari EZ, Dadgostar H, Askari A, Arasteh P. Treatment of concomitant ACL and MCL injuries: Spontaneous healing of complete ACL and MCL tears. J Knee Surg 2021;34:1329-36. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Halinen J, Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E, Santavirta S. Operative and nonoperative treatments of medial collateral ligament rupture with early anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective randomized study. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:1134-40. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang H, Sun Y, Han X, Wang Y, Wang L, Alquhali A, et al. Simultaneous reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament in patients with chronic ACL-MCL lesions: A minimum 2-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:1675-81. [Google Scholar]

- 19. LaPrade RF, Chahla J. Evidence-Based Management of Complex Knee Injuries: Restoring the Anatomy to Achieve Best Outcomes. New York: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020. p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshiya S, Kuroda R, Mizuno K, Yamamoto T, Kurosaka M. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction using autogenous hamstring tendons: Technique and results in initial cases. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:1380-5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laprade RF, Wijdicks CA. Surgical technique: Development of an anatomic medial knee reconstruction. ClinOrthop Relat Res 2012;470:806-14. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gupta S, Ashish BC, Chavan SK, Gupta P. Reconstruction of Superficial medial collateral ligament: Modified Danish technique with dual adjustable loop suspensory fixation. Arthrosc Tech 2023;12:e2141-51. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joshi A, Singh N, Thapa S, Pradhan I. Weave technique for reconstruction of medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament: An anatomic approach using semitendinosus tendon. Arthrosc Tech 2019;8:e1417-23. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wijdicks CA, Brand EJ, Nuckley DJ, Johansen S, LaPrade RF, Engebretsen L. Biomechanical evaluation of a medial knee reconstruction with comparison of bioabsorbable interference screw constructs and optimization with a cortical button. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:1532-41. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watson ST, Pichiotino ER, Adams JD. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction with dual adjustable-loop suspensory fixation: A technique guide. Arthrosc Tech 2021;10:e621-8. [Google Scholar]