Hip abductor muscle strength post-hip arthroplasty plays a key role in maintaining pelvic stability, facilitating hip movements, and ensuring efficient gait mechanics.

Dr. P Pradeep, Department of Orthopaedics, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: jppradeep.dr@gmail.com

Aims and Background: A subset of people has persistent functional impairment due to hip abductor muscle weakness post-hip arthroplasty. Hip abductor muscles collectively play a crucial role in maintaining pelvic stability, facilitating hip movements, and ensuring efficient gait mechanics. We aimed to prospectively evaluate the static abductor strength and lower extremity strength in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty and it’s effect on functional outcome.

Materials and Methods: Twenty patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) or bipolar hemiarthroplasty were included in our study. Their static and dynamic hip abductor strength was prospectively assessed at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. Static abductor strength was measured using dynamometer and manual muscle testing, while dynamic abductor strength using 6 min walk test, stand and sit test, and timed up go test and its effect on functional outcome by Harris Hip Score (HHS).

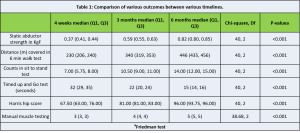

Results: Of 20 patients in our study, 16 underwent hemiarthroplasty and four underwent THA. Posterolateral approach was the most used approach. The median static abductor strength at 4 weeks was 0.37 kgf, 3 months was 0.59 kgf, and 6 months was 0.82 kgf (P < 0.001) which is statistically significant. Dynamic abductor strength was checked using 6- min walk test which showed improvement from 230 m at 4 weeks to 446 m at 6 months. Counts in sit and stand test increased from a median of 7 at 4 weeks to 14 at 6 months. Timed up and go test decreased from 32 s in 4 weeks to 15 s in 6 months. The functional outcome assessed by HHS showed 67. 50 at 4 weeks to 96 at 6 months.

Conclusion: My study confirms that there is significant improvement in hip static and dynamic abductor strength and functional outcome within 6 months following hip arthroplasty. The lateral approach for hip arthroplasty has better static hip abductor strength than the posterolateral approach. There is no statistically significant difference in hip abductor strength recovery between THA and bipolar hemiarthroplasty.

Keywords: Hip arthroplasty, abductor muscle strength, gait mechanics.

The human hip joint, the largest ball and socket joint in the body, is designed to meet the demands of ambulation and weight-bearing activities [1]. The cup-shaped acetabulum of the hip joint is formed by the innominate bone, comprising contributions from the ilium (40%), ischium (40%), and pubis (20%) [2]. In skeletally immature individuals, these bones are separated by the triradiate cartilage, which begins to fuse around ages 14–16 and completes by age 23 [3]. The acetabulum features a lunate-shaped articular surface, with a central area known as the central inferior acetabular fossa, housing a synovial-covered fat pad, and the acetabular attachment of the ligamentum teres. The acetabular socket is completed by the inferior transverse ligament [4]. Although labrum contributes less to joint stability, it helps restrict synovial fluid movement to the peripheral compartment of the hip, exerting a negative pressure effect [5]. The primary hip abductor muscles – gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae – along with secondary abductors such as the piriformis, sartorius, and superior fibers of the gluteus maximus, play a crucial role in stabilizing the pelvis [6]. Weakness in these muscles can lead to an unstable pelvis and impaired gait mechanics, highlighting their importance in everyday movements. Proper function of the hip abductors is therefore vital for both effective movement and managing conditions that affect hip stability and comfort [7]. Despite the importance of hip abductor strength in post-surgical rehabilitation, there is still much to learn about its specific impact on functional outcomes [8]. While clinical observations and anecdotal evidence suggest a relationship between hip abductor weakness and suboptimal recovery, a comprehensive investigation is needed to better understand this connection [9]. Our study aims to address this gap in knowledge by conducting a thorough examination of hip abductor strength in patients undergoing hip replacement surgery. By evaluating both the static strength of the hip abductors and the overall strength of the lower extremities, this study seeks to determine the extent to which hip abductor strength influences functional recovery post-surgery [10]. By gaining a deeper understanding of these relationships, we hope to identify effective strategies for optimizing rehabilitation protocols and improving outcomes for individuals undergoing hip replacement surgery and ensuring that they have benefits of improved mobility and reduced pain for years to come [11]. The aim of this study is to evaluate the hip abductor strength post-hip arthroplasty and its effect on functional outcome, to evaluate the static abductor strength in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty, and to evaluate the dynamic abductor strength and lower extremity strength in patients undergoing hip arthroplasty.

Our study is a prospective observational study of 20 patients who underwent hip arthroplasty in our institute between November 2023 and May 2024. Our study included patients above 50 years of age, both males and females who had unilateral hip arthritis and fracture neck of femur. Patients with Bilateral hip arthritis, polyarthritis, secondary arthritis with fixed deformity, ipsilateral surgical history in the past, joint ankylosis or stiffness, musculoskeletal impairments, and ipsilateral total knee arthroplasty were excluded in our study.

Hip abductor function assessment

Static abductor

Dynamometer

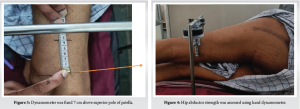

Using a handheld dynamometer (Fig. 1) fixed against a solid bar. Patient is in lateral decubitus position with the operated side above. Patient will be asked to abduct the hip joint against the dynamometer which is placed at a distance of 7 cm from the superior pole of patella and hold for a period of 5 s and measure the abduction strength in kgf. Repeat the procedure for 3 times. Now repeat the same procedure for the contralateral hip. The study was carried out at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months (Fig. 2, 3, and 4).

Manual muscle testing

On lateral decubitus position with the operated side above, using medical research council (MRC) grading system, check for the power of hip abduction at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

Dynamic abductor

6 min walk test

We use a 30 m indoor walkway. The start and end point was marked with a cone. The patient should take a rest of about 5 min before the start of the test. Measure the total number of laps the patient can walk in 6 min and calculate the total distance in meter. I will repeat the test for 3 times with 10 min interval between two test. The average distance covered will be measured. The study was carried out at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months (Fig. 5).

Stand and sit tests (SSTs)

Test performed for 30 s. Ask the patient to stand and Sit for 30 s. Total number of stand and sit repeat is counted. Test is performed for 2 times. Average count is noted. The study was carried out at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months (Fig. 6).

Timed up and go (TUG) test

Time was taken to complete the test in seconds. Test is repeated for 2 times. Average of 2 is taken in seconds. The study was carried out at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months (Fig. 7).

Harris hip score (HHS)

The analysis was carried out at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

Case illustration – I: Fig. 8

Static and dynamic abductor strength was assessed at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

Readings at 4 weeks postoperatively:

- A: Static dynamic strength: 0.51 1 B: MRC grading: Grade 3.

- 6 min walk test: 230 m 3: SST: 7 Count.

- TUG test: 29 s 5: HHS: 63.

Readings at 3 months postoperatively:

1 A: Static dynamic strength: 0.68 1 B: MRC grading: Grade 4.

2: 6 min walk test: 345 m 3: SST: 11 Count.

4: TUG test: 20 s 5: HHS: 81.

Readings at 6 months postoperatively

- A: Static dynamic strength: 0.84 1 B: MRC grading: Grade 5.

- 6 min walk test: 455 m 3: SST: 14 Count.

- TUG test: 16 s 5: HHSs: 96.

Case illustration – II: Fig. 9

Static and dynamic abductor strength was assessed at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

Readings at 4 weeks postoperatively:

- A: Static dynamic strength: 0.4 1 B: MRC grading: Grade 3.

- 6 min walk test: 206 m 3: SST: 5 Count.

- TUG test: 42 s 5: HHS: 63.

Readings at 3 months postoperatively:

- A: Static dynamic strength: 0.59 1 B: MRC grading: Grade 4.

- 6 min walk test: 306 m 3: SST: 9 count.

- TUG test: 30 s 5: HHS: 76.

Readings at 6 months postoperatively:

- A: Static dynamic strength: 0.78 1 B: MRC grading: Grade 5.

- 6 min walk test: 416 m 3: SST: 11 count.

- TUG test: 16 s 5: HHS: 96.

The median age of the participants was 66 years, with ages ranging from 52 to 85 years. The gender distribution of the participants was 9 males (45%) and 11 females (55%). Regarding past medical and surgical history, 11 participants (55%) had no significant medical history, 5 participants (25%) had systemic hypertension, 3 participants (15%) had type 2 diabetes mellitus, and 1 participant (5%) had hepatitis B. The diagnosis for the participants was distributed as follows: 9 participants (45%) had a left neck femur fracture, 7 participants (35%) had a right neck femur fracture, 3 participants (15%) had left hip primary arthritis, and 1 participant (5%) had right hip primary arthritis. Concerning the approach used for surgery, 3 participants (15%) underwent a lateral approach, while 17 participants (85%) underwent a posterolateral approach. As for the procedures performed, 14 participants (70%) had a bipolar hemiarthroplasty, and 6 participants (30%) had a total hip arthroplasty (THA). The period of immobilization before surgery had a median of 4 days. The duration of surgery had a median of 62.50 min. The post-operative day of mobilization was consistently 12 days, indicating that all patients were mobilized on the 12th day post-operation. At 4 weeks, the median static abductor strength was 0.40 kgf for posterolateral and 0.44 kgf for lateral (P = 0.312). At 3 months, medians were 0.58 kgf and 0.64 kgf, respectively (P = 0.056), and at 6 months 0.81 kgf and 0.86 kgf (P = 0.029). The static abductor strength at 6 months showed statistically significant difference for lateral approach than posterolateral approach. At 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months, the median static abductor strength showed statistically no significant difference for THA and bipolar hip arthroplasty. The median static abductor strength at 4 weeks was 0.37 kgf, 3 months was 0.59 kgf, and 6 months was 0.82 kgf (P < 0.001) which is statistically significant. Manual muscle testing was evaluated using MRC grade which showed progressive increasing trend of grade 3 at 4 weeks to Grade 4 at 3 months to Grade 5 at 6 months (P < 0.001). While dynamic abductor strength was checked using 6 min walk test, SST, and TUG test. The distance covered 6 min walk test improved from 230 m at 4 weeks to 340 m at 3 months and 446 m at 6 months (P < 0.001). Counts in the SST increased from median of 7.00 at 4 weeks to 10.50 at 3 months and 14 at 6 months (P < 0.001). The TUG test times decreased from 32 s in 4 weeks to 22 s in 3 months to 15 s in 6 months (P < 0.001). All dynamic abductor strength assessment showed statistically significant results. The functional outcome was assessed using HHS at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months which showed from 67.50 at 4 weeks to 81.00 at 3 months and 96.00 at 6 months. In our study, the improvement in static and dynamic abductor strength following HA have a positive prognostic effect on the HHS at the end of 6 months (Table 1).

The findings of our study contribute to the growing body of literature on the recovery of hip abductor muscle strength following THA and bipolar hemiarthroplasty [12]. Our results demonstrate significant improvements in static abductor strength, manual muscle testing scores with MRC grading and dynamic abductor strength by distance covered in the 6-min walk test, counts in the SST, TUG test times, and HHSs over a 6-month period postoperatively. These improvements are consistent with the existing literature, which highlights the progressive recovery of hip abductor muscle strength and overall function after hip arthroplasty. Our study found a significant increase in static abductor strength from a median of 0.37 kgf at 4 weeks to 0.82 kgf at 6 months postoperatively. This aligns with the findings of Ismailis et al. [13], who reported progressive improvements in hip abductor strength at various intervals post-THA, with a 49.8% increase at 18–24 months compared to pre-operative values. However, despite these improvements, Ismailis et al. indicate that hip abductor strength does not fully recover to the level of the healthy contralateral side even after extended follow-up periods. However, in our study, extended periods of follow-up were not done. The manual muscle testing scores in our study showed a consistent improvement from a median of 3 at 4 weeks to 5 at 6 months. This is in line with the systematic review findings [14], which also reported gradual improvements in muscle strength postoperatively. Our study’s findings on the 6-min walk test, which showed an increase from 230 m at 4 weeks to 446 m at 6 months, align with previous research indicating enhanced functional capacity and endurance over time. While previous studies did not specifically use the 6-min walk test, the observed improvement in functional outcomes is consistent with general trends reported in the literature [15]. In terms of the SST, our results showed a significant increase in the number of counts from a median of 7 at 4 weeks to 14 at 6 months. The TUG test times in our study decreased from a median of 32 s at 4 weeks to 15 s at 6 months, reflecting improved mobility and balance. The HHSs in our study improved from a median of 67.50 at 4 weeks to 96.00 at 6 months, indicating substantial recovery in hip function and patient satisfaction. Our study did not find significant differences in outcomes between the lateral and posterolateral surgical approaches, which contrasts with some literature suggesting varying impacts on muscle strength recovery based on surgical technique. For instance, Rosenlund et al. (2016) reported better outcomes for hip abductor strength with the posterior approach compared to the lateral approach. However, our results did show a trend toward better static abductor strength at 6 months in the lateral approach group, which warrants further investigation with a larger sample size. Similarly, no significant differences were found between THA and bipolar hemiarthroplasty in our study, although the latter showed a trend toward higher HHSs and better performance in the 6-min walk test and TUG test at later follow-up. This suggests that both procedures are effective in improving hip function and muscle strength, but patient-specific factors and surgical technique nuances might influence the choice of procedure and its outcomes.

Strengths, Limitations

One limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size, particularly in the comparison of different surgical approaches and procedures. In addition, the absence of a healthy control group prevents direct comparison of recovery levels to normal hip function. The strengths of this research are manifold. It utilized a comprehensive set of outcome measures, including static abductor strength, manual muscle testing, 6-min walk test, SST, TUG test, and HHSs, allowing for a thorough assessment of both muscle strength and functional recovery.

Our study confirms that there are significant improvements in hip static and dynamic abductor strength and functional outcomes can be achieved within 6 months following hip arthroplasty. The lateral approach for hip arthroplasty has better static hip abductor strength at 6 months than the posterolateral approach. There is no statistically significant difference in hip abductor strength recovery between THA and bipolar hemiarthroplasty. These findings are consistent with the broader literature, underscoring the importance of comprehensive rehabilitation programs and the need for personalized approaches to optimize recovery for patients undergoing hip replacement surgery.

Hip arthroplasty is done to offer pain relief and restoration of function. Hip abductor muscle strength both static and dynamic is essential for pelvic stability, efficient gait mechanics post-hip arthroplasty. We assessed these parameters and suggested rehabilitation protocol following hip arthroplasty.

References

- 1. Anderson LC, Blake DJ. The anatomy and biomechanics of the hip joint. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 1994;4:145-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Schünke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U, Lamperti ED. Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2006. p. 541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Moore K, Dalley AF, Agur AM. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Byrne DP, Mulhall KJ, Baker JF. Anatomy and biomechanics of the hip. Open Sports Med J 2010;4:51-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kim YH. Acetabular dysplasia and osteoarthritis developed by an eversion of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;215:289-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Thomas Byrd JW. Indications and contraindications. In: Thomas Byrd JW, editor. Operative Hip Arthroscopy. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 6-35. Available from: ??? [Last accessed on 2024 May 20]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Mansfield P. Essentials of kinesiology for the physical therapist assistant. In: Structure and Function of the Hip. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 233-77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Melegrito RA. Medically reviewed by wiznia D. In: Bipolar Hemiarthroplasty. United Kingdom: Medical News Today; 2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Total Hip Replacement – Ortho Info – AAOS. Available from: https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/treatment/total-hip-replacement [Last accessed on 2024 May 22]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Singh A. Bipolar Hemiarthroplasty vs. Total Hip Replacement; 2023. Available from: https://knyamed.com/blogs/difference/between/bipolar/hemiarthroplasty/vs/total/hip/replacement [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Menschik F. The hip joint as a conchoid shape. J Biomech 1997;30:971-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Romain G, Henri M, Paul EB. Hip Anatomy and Biomechanics Relevant to Hip Replacement. Ch. 2. 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk565771 [Last accessed on 2024 May 20]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Lespasio MJ, Sultan AA, Piuzzi NS, Khlopas A, Husni ME, Muschler GF, et al. Hip osteoarthritis: A primer. Perm J 2018;22:17-084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ismailidis P, Kvarda P, Vach W, Cadosch D, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Mündermann A. Abductor muscle strength deficit in patients after total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2021;36:3015-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Aggarwal VK, Iorio R, Zuckerman JD, Long WJ. Surgical approaches for primary total hip arthroplasty from charnley to now: The quest for the best approach. JBJS Rev 2020;8:e0058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]