Vitamin D supplementation, when used alongside standard therapy, not only reduces pain and improves functional outcomes in patients with knee osteoarthritis but also helps in slowing down cartilage loss.

Dr. Siddharth Singh, Department of Orthopedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: siddharth271295@gmail.com

Introduction: Vitamin D treatment reduces osteoarthritis (OA) pain, inflammation, and cartilage degradation, indicating that it may have therapeutic advantages in the management of OA symptoms. Thus, the present study was conducted to assess the effect of Vitamin D in treatment of Knee OA.

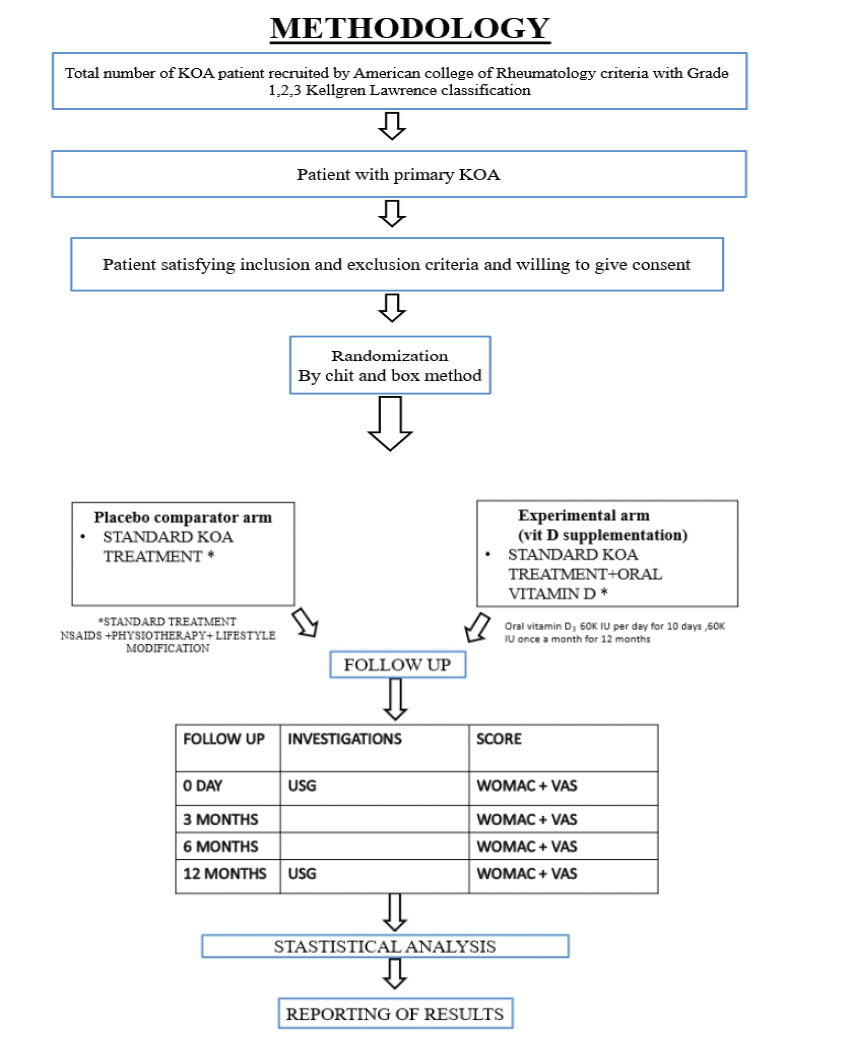

Materials and Methods: A randomized control study was done on 78 cases, fulfilling American College of Rheumatology criteria for diagnosis of OA knee. Patients were randomized into an experimental (vitamin D supplement along with standard treatment for Knee OA [KOA]) and placebo group (standard treatment for KOA). All patients were followed up from baseline till 12 months. Pain was assessed using Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and functional outcome by Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score. Cartilage thickness of medial, sulcus, and lateral femoral condyle was evaluated at baseline and after a year using ultrasound imaging. Data collected and recorded on MS Excel. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 software.

Results: Mean VAS and WOMAC score were comparable (P > 0.05), but less in experimental than placebo group at all-time intervals. Average cartilage thickness of medial and lateral femoral condyle was comparable (P > 0.05), but more in experimental than placebo group. Average cartilage thickness of sulcus femoral condyle was considerable (P < 0.05) and more in experimental than placebo group at 12 months. Thickness of cartilage decreased in both groups from baseline to 12 months; but not considerably (P > 0.05) in experimental group.

Conclusion: Patients with OA discomfort in their knees were benefited in terms of pain and functionality, after taking Vitamin D supplements. There is a necessity of standardized, carefully planned studies to gain a deeper understanding of vitamin D’s function in KOA treatment.

Keywords: Knee, osteoarthritis, Vitamin D, cartilage, pain.

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a common musculoskeletal problem worldwide affecting 3.8% of the world’s population [1,2]. The prevalence of KOA is expected to increase dramatically in low and middle-income nations [3]. Thereby causing a substantial direct and indirect economic burden [3].

Where there are clear guidelines on the surgical management of OA, there is a lack of any consensus on the role of conservative management in the treatment of OA. Vitamin D, mesenchymal stem cells, intra-articular corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid, and platelet-rich plasma injections have been used in past with varying results [4]. Vitamin D in particular has got a lot of attention as Vitamin D deficiency has been found to be associated with Knee OA [5]. Low levels of Vitamin D may alter the stability of cartilage metabolism by reducing the synthesis of proteoglycan and/or increasing the metalloproteinases activity, leading to cartilage loss [4]. It has been reported that Vitamin D supplementation can aid in regeneration of articular cartilage, provide pain relief, and can improve the physical functions [6,7].

Although in vitro studies have demonstrated the role of Vitamin D in promoting articular cartilage regeneration [8], there is a notable lack of clinical trials evaluating its efficacy in regenerating cartilage and preventing its degeneration in human subjects.

Therefore, a study is warranted to evaluate the efficacy of Vitamin D supplementation in promoting cartilage regeneration, alleviating pain, and improving physical function in patients with KOA.

This prospective, comparative study was undertaken at a tertiary care institution over a period of 16–18 months (from November 21, 2023 to April 01, 25).

The study comprised 78 patients of both sexes, aged over 20 years, who were diagnosed with primary KOA based on anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knee joints. Radiographic severity was graded according to the Kellgren and Lawrence classification system (Grades I-III). In addition, all participants satisfied the diagnostic criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology for KOA. Patients with secondary forms of KOA, prior surgical intervention, or history of fracture involving the index knee, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, disorders of the thyroid or parathyroid glands, any malignancy, chronic hepatic or renal disease, known hypersensitivity to Vitamin D or any study-related substances were excluded from the study.

Before the initiation of the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (TMU/IEC November 23/120).

Eligible participants (n = 78) were randomly allocated into two groups using the chit-and-box randomization technique: Experimental Group who received oral Vitamin D supplementation in conjunction with the standard treatment protocol for KOA and placebo group who received standard KOA treatment alone.

The standard treatment regimen comprised indomethacin (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug), administered orally at a dose of 3 times daily for 2 weeks, with subsequent use on an as-needed (SOS) basis along with structured physiotherapy, lifestyle, and activity modifications.

The Vitamin D supplementation protocol included oral administration of Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) at a dose of 60,000 IU daily for 10 consecutive days, followed by 60,000 IU once monthly for the subsequent 12 months.

All participants underwent comprehensive follow-up assessments at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. The outcome measures recorded were pain intensity, assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and functional status, evaluated using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC).

In addition, ultrasonographic evaluation of femoral cartilage thickness (medial, intercondylar sulcus, and lateral regions) was conducted at bas and at the 12-month follow-up to monitor structural changes.

All data were systematically recorded in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Chicago Ltd).

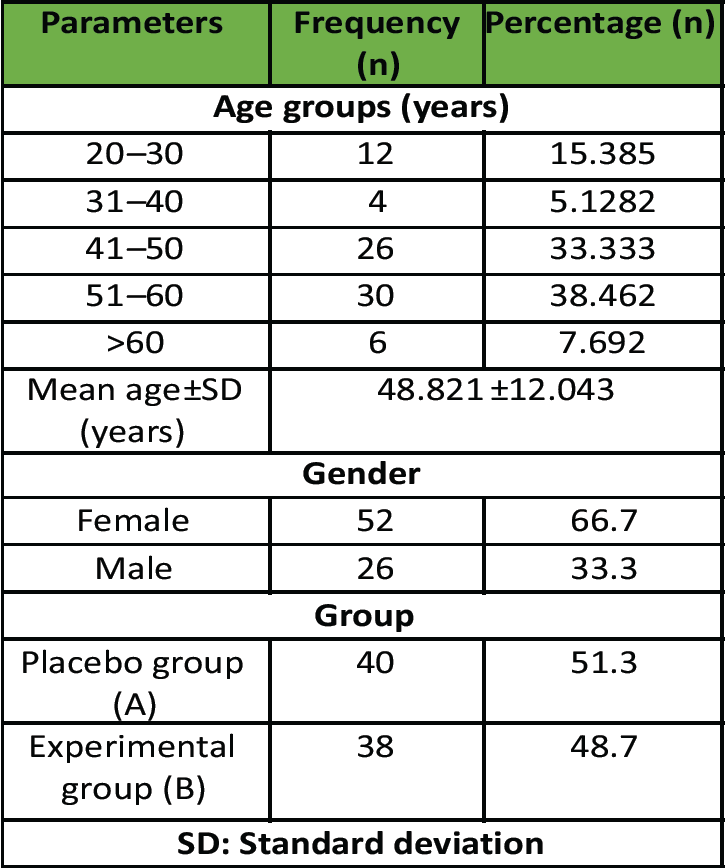

A female predominance was observed among the study participants, accounting for 66.7% of the total cases. The majority of subjects (38.5%) were aged between 51 and 60 years, with a mean age of 48.8 years. The study included 78 participants, who were randomly assigned into two groups: Group A (placebo group, 51.3%) and Group B (experimental group, 48.7%) (Table 1). The majority of participants in Group A (57.5%) and Group B (52.6%) presented with Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) Grade 3 osteoarthritis (OA). The distribution of KL grades between the groups showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05).

Table 1: Distribution of study subjects according to demographic parameters

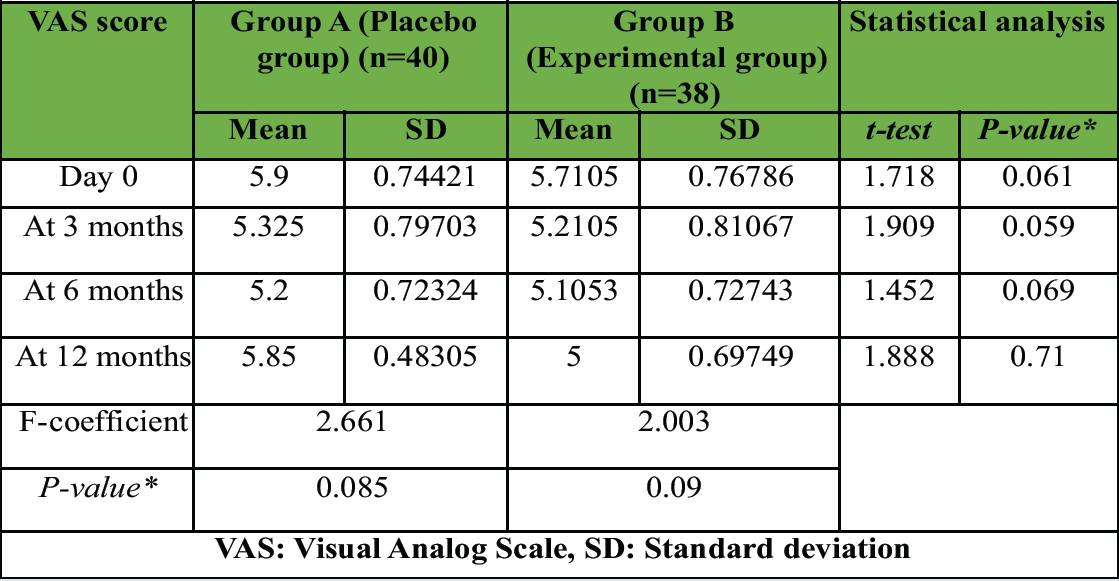

The mean pain scores were evaluated in both groups from baseline to 12 months. Although the pain scores were comparable between groups (P > 0.05), the experimental group consistently demonstrated lower scores than the placebo group at all time points. In the experimental group (Group B), pain scores showed a continuous decline from baseline through 12 months. In contrast, the placebo group (Group A) exhibited a reduction in pain scores up to 6 months, followed by an increase at 12 months (Table 2).

Table 2: Average VAS score

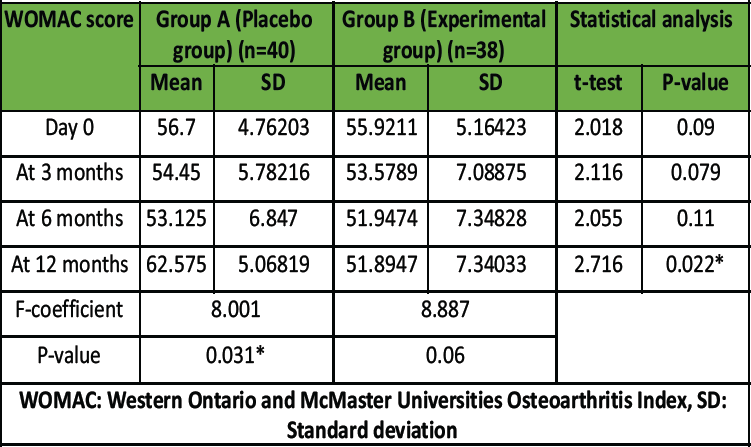

At baseline, the mean WOMAC scores were comparable between Group A (56.70 ± 4.76) and Group B (55.92 ± 5.16), with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.090). Similar non-significant differences were observed at 3 months (P = 0.079) and 6 months (P = 0.110).

However, by 12 months, a statistically significant difference in WOMAC scores was observed between the two groups. Group A showed a marked increase in WOMAC score (62.58 ± 5.07), indicating worsening symptoms, whereas Group B maintained a lower score (51.89 ± 7.34), reflecting sustained improvement. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.022; t-test = 2.716) (Table 3).

Table 3: Average WOMAC score

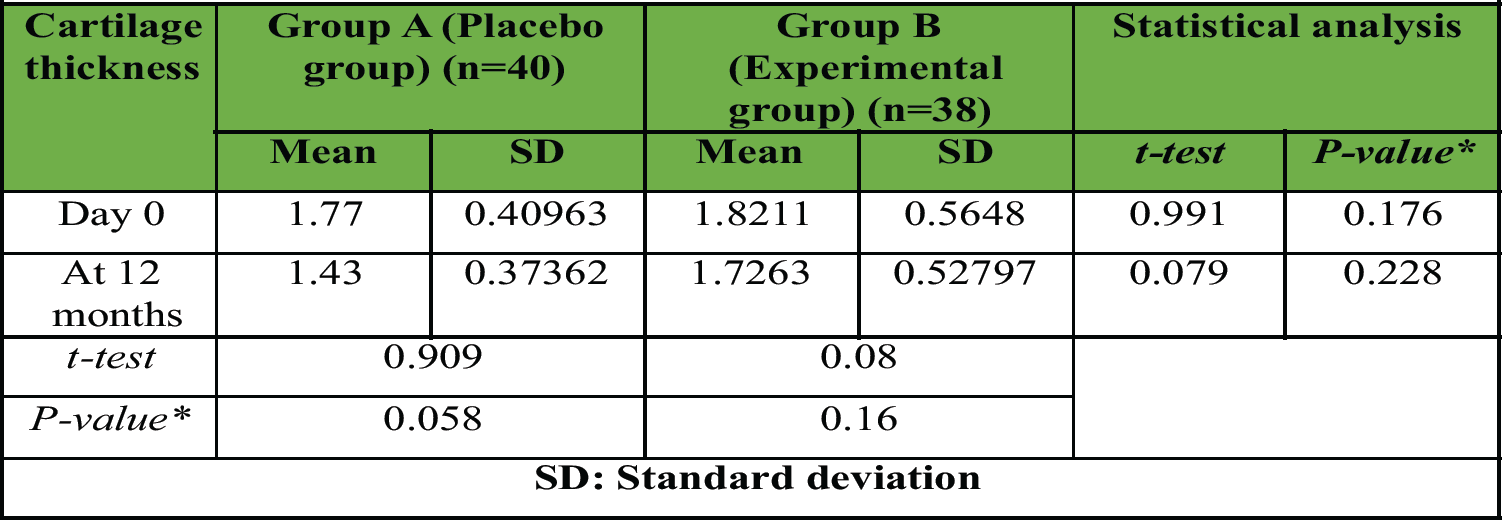

At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in cartilage thickness between Group A (1.7700 ± 0.4096 mm) and Group B (1.8211 ± 0.5648 mm; P = 0.176). After 12 months, both groups exhibited a reduction in cartilage thickness. Group A decreased to 1.4300 ± 0.3736 mm and Group B to 1.7263 ± 0.5279 mm. The difference between the groups at 12 months remained statistically non-significant (P = 0.228).

Within-group comparisons showed a reduction in cartilage thickness over time in both groups; however, these changes were not statistically significant. The within-group P-value for Group A was 0.058 and for Group B was 0.160 (Table 4).

Table 4: Average cartilage thickness of medial femoral condyle

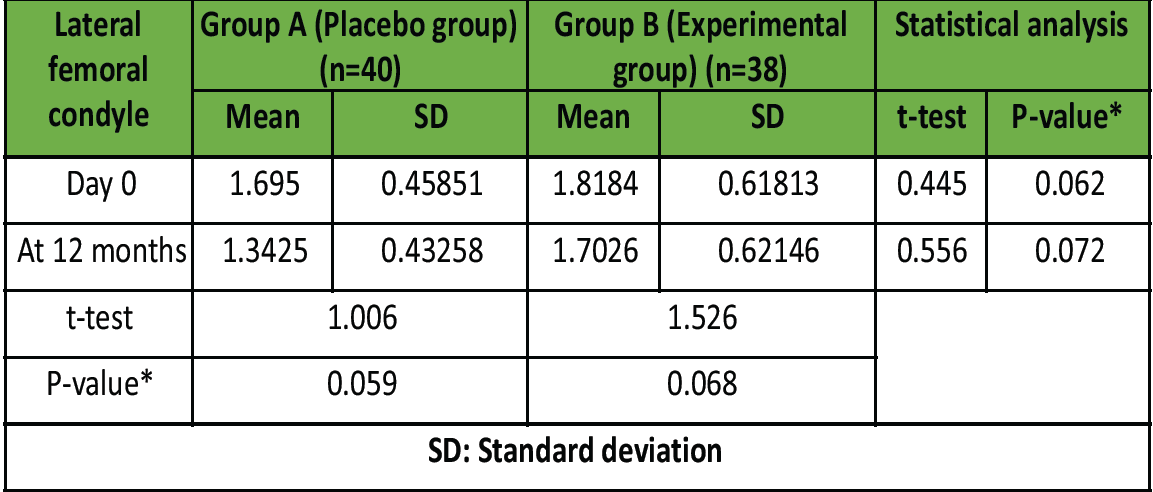

At baseline, the mean cartilage thickness of the lateral femoral condyle was slightly higher in the experimental group (1.8184 ± 0.6181 mm) compared to the placebo group (1.6950 ± 0.4585 mm), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.062). At 12 months, both groups showed a reduction in cartilage thickness. The placebo group declined to 1.3425 ± 0.4326 mm, while the experimental group declined to 1.7026 ± 0.6215 mm. However, this intergroup difference also remained statistically non-significant (P = 0.072).

Within-group comparisons showed reductions in cartilage thickness over time in both groups, with P = 0.059 (Group A) and 0.068 (Group B), indicating trends toward significance, though not reaching the conventional threshold (P < 0.05).

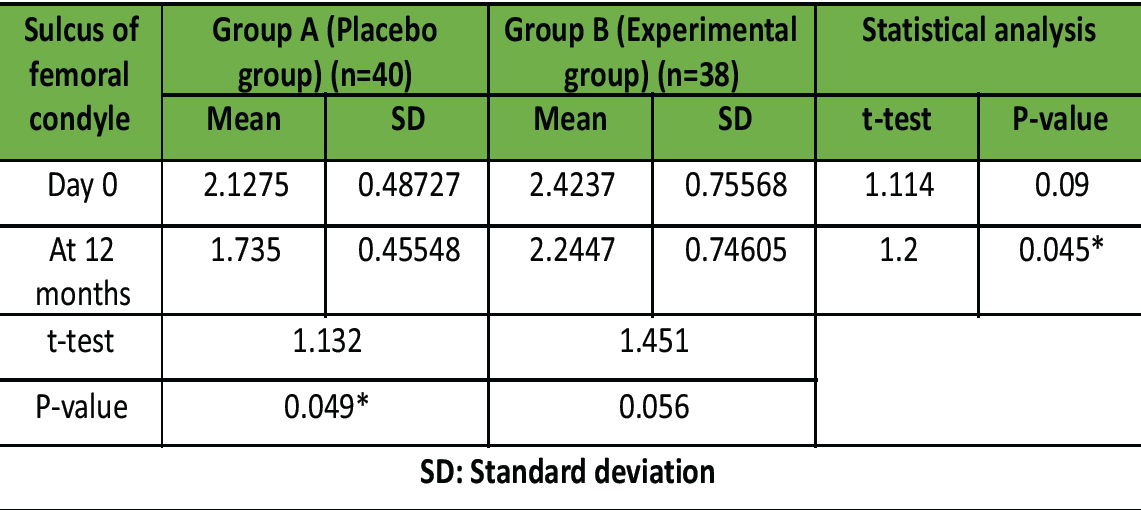

At baseline, the mean cartilage thickness of sulcus of femoral condyles was similar between groups, with Group A recording 2.1275 ± 0.4873 mm and Group B 2.4237 ± 0.7557 mm, showing no statistically significant difference (P = 0.090). At the 12-month follow-up, Group A showed a notable reduction in cartilage thickness (1.7350 ± 0.4555 mm), whereas Group B maintained a higher mean thickness (2.2447 ± 0.7461 mm). The difference between the two groups at 12 months was statistically significant (P = 0.045; t = 1.200). Within-group analysis demonstrated a statistically significant decline in cartilage thickness over time in Group A (P = 0.049), while the experimental group showed no significant reduction (P = 0.056) (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5: Average cartilage thickness of lateral femoral condyle at different time intervals

Table 6: Average cartilage thickness of sulcus of femoral condyle at different time intervals

In our trial, we found female predominance (66.7%), with average age being 48.8 years. Likewise, Arden et al. [9] depicted female predominance (>60%) with average age of 64 years. Wang et al., [10] revealed that average age of cases of KOA was 61.8 years, with 63.5% females. Thati [11] revealed female predominance (51%); with incidence increasing with age. Most cases in our research had KL Grade 3. In study by, Jin et al. [12] revealed with 44% of KL Grade 3 and 56% of Grade 2.

We found that in the experimental group, pain scores were less than placebo. Likewise, Jin et al. [12] also revealed that Vitamin D supplementation had a considerable effect on pain scores, showing an evident decrease. Wang et al. [10] revealed a considerable decrease in VAS score with time, in cases with Vitamin D supplements. Similarly, Sanghi et al. [13] also recognized a similar decrease in knee’s pain score by using Vitamin D supplements. Manoy et al. [14] depicted a considerable betterment in VAS score with Vitamin D supplementation.

We found that in the experimental group, WOMAC scores were less than placebo. WOMAC score decreased in Group B, but not considerably. In group A, WOMAC scores decreased at 6 months and then increased considerably. Wang et al. [10] revealed a considerable decrease in WOMAC score with time, though this decrease was considerable in Vitamin D supplementation. Zheng et al. [15] revealed that WOMAC scores showed improvement with vitamin D supplements. Sanghi et al. [13] also stated that KOA patients, Vitamin D treatment did help with WOMAC pain reduction and functional improvement. Improved function of joint and WOMAC score further supported the vitamin’s capacity to reduce pain and enhance quality of life in KOA patients. Zuo et al. [16] observed a considerable linear association of Vitamin D supplements in improving WOMAC scores.

Average cartilage thickness of medial and lateral femoral condyle was comparable (P > 0.05), but more in experimental than control group. Thickness decreased in both groups from baseline to 12 months; but not considerably (P > 0.05). Average cartilage thickness of sulcus femoral condyle was considerable (P < 0.05) and more in the experimental than placebo group at 12 months. Thickness of cartilage decreased in both groups from baseline to 12 months, but not considerably (P > 0.05) in the experimental group. Jin et al. [12] also revealed that Vitamin D supplementation had a considerable effect on cartilage thickness. Zheng et al. [15] revealed that cartilage thickness decreased considerably in cases with Vitamin D supplements as compared to placebo.

Our study had limitations of having a limited sample size, thus future studies are recommended to be carried on a larger sample. This research is dependent on the outcomes taken from a single center, so the results could not be applied to whole Indian population. Our suggestion is to do more number of prospective research studies as well as clinical trials involving elaborated population of India, so as to generalize the study results. There is considerable variation throughout research about the dosage, type of Vitamin D (D2 ergocalciferol or D3 cholecalciferol), and treatment duration because there is no agreement on the typical duration of Vitamin D administration. It was challenging to reach firm findings regarding the long-term efficacy because different trials had different outcomes and varied follow-up times.

For individuals with KOA, Vitamin D treatment has various advantages. It increases muscle strength, decreases inflammation, lesser pain perception, and improves quality of life. According to this study, persons with OA discomfort in their knees may benefit from taking Vitamin D supplements. Comprehensive studies on the amount of Vitamin D in the blood as well as various Vitamin D formulations, dosages, and treatment plans, should be carried out in the future.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. The sample size was relatively small and conducted at a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the wider population. Second, serum Vitamin D levels were not measured, so the direct correlation between baseline deficiency, achieved Vitamin D status, and clinical outcomes could not be established. Safety monitoring for toxicity was omitted, and confounders such as body mass index, sun exposure, and physical activity were not controlled. Third, the follow-up period was limited to 12 months, which may not adequately capture long-term effects of supplementation on the structural progression of knee OA. Finally, variability in individual compliance to Vitamin D supplementation and lifestyle modifications may have influenced the results. This study is limited by weak randomization (chit-and-box method), absence of blinding, and reliance on ultrasound – an operator-dependent tool – instead of magnetic resonance imaging for cartilage assessment. These limitations reduce the strength of the conclusions and highlight the need for larger, better-designed multicenter trials.

Routine Vitamin D supplementation in patients with knee OA can be a simple, cost-effective, and safe adjunct to conventional management, providing symptomatic relief and potential structural benefits. Larger, multicentric trials are warranted to establish standard dosage protocols and long-term efficacy.

References

- 1. Wieland HA, Michaelis M, Kirschbaum BJ, Rudolphi KA. Osteoarthritis – an untreatable disease? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2005;4:331-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Das SK, Farooqi A. Osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2008;22:657-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Jang S, Lee K, Ju JH. Recent updates of diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment on osteoarthritis of the knee. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:2619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Vaishya R, Vijay V, Lama P, Agarwal A. Does vitamin D deficiency influence the incidence and progression of knee osteoarthritis? – A literature review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019;10:9-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Gao XR, Chen YS, Deng W. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on knee osteoarthritis: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg 2017;46:14-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Diao N, Yang B, Yu F. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Biochem 2017;50:1312-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Muraki S, Dennison E, Jameson K, Boucher BJ, Akune T, Yoshimura N, et al. Association of vitamin D status with knee pain and radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:1301-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Arden NK, Cro S, Sheard S, Doré CJ, Bara A, Tebbs SA, et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on knee osteoarthritis, the VIDEO study: A randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1858-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Wang R, Wang ZM, Xiang SC, Jin ZK, Zhang JJ, Zeng JC, et al. Relationship between 25-hydroxy vitamin D and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Med 2023;10:1200592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Thati S. Gender differences in osteoarthritis of knee: An Indian perspective. J Midlife Health 2021;12:16-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Jin X, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Wluka A, Zhu Z, Han W, et al. Effect of Vitamin D supplementation on tibial cartilage volume and knee pain among patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:1005-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Sanghi D, Mishra A, Sharma AC, Singh A, Natu SM, Agarwal S, et al. Does vitamin D improve osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;11:3556-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Manoy P, Yuktanandana P, Tanavalee A, Anomasiri W, Ngarmukos S, Tanpowpong T, et al. Vitamin D supplementation improves quality of life and physical performance in osteoarthritis patients. Nutrients 2017;9:799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Zheng S, Tu L, Cicuttini F, Han W, Zhu Z, Antony B, et al. Effect of Vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:1634-40.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Zuo A, Jia Q, Zhang M, Zhou X, Li T, Wang L. The association of vitamin D with knee osteoarthritis pain: An analysis from the osteoarthritis initiative database. Sci Rep 2024;14:30176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]