Timely diagnosis, anatomical reduction of ulna fracture by restoring the length and angulation and confirming intraoperative radial head reduction are a key to manage the Monteggia fractures and avoiding revision surgery.

Dr. Yogesh Mudholkar, Department of Orthopaedics, Seth G.S. Medical College and King Edward Memorial Hospital, 82 A/6A 44 SBI Colony Bhawani Peth, Solapur - 413002, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: yogeshmudholkar4@gmail.com

Introduction: Missed lesions, myositis, nerve palsies, and compartment syndrome are the listed complications of Monteggia fracture dislocations. There is a lot of literature on missed or neglected Monteggia fractures, but we could not find any series or studies on how to tackle failed primary fixations. We report the first case series of analysis and management of failed fixation of Monteggia fractures.

Materials and Methods: In this case series, we discuss four cases that were identified as failure of fixation of the Monteggia fracture dislocation. Three children, 6-year-old female child, 7-year-old male child, 6-year-old male child, and one adult male of 39 years of age were operated on with open or closed reductions of the forearm fractures with rigid or flexible fixation. Two of these patients presented with Bado Type I, one with Type I equivalent and one Type IV fracture. In all the cases, the surgeon had correctly diagnosed the Monteggia fracture but was unable to reduce and fix it properly. We discuss the technical reasons for failure and the process by which they were corrected. After the revision surgery, the anatomy was restored in all the patients and the functional outcome was satisfactory.

Conclusion: Based on these cases, the authors conclude that a thorough clinical evaluation, careful pre-operative assessment of potential failure factors, and meticulous surgical planning are essential to reduce the risk of revision surgeries and prevent further complications.

Keywords: Monteggia, radiocapitellar joint, failed fixation, revision surgery.

First described in the year 1814, by Giovanni Battista Monteggia, the Monteggia fracture dislocation refers to a group of fractures of the proximal ulna with radiocapitellar joint and proximal radio-ulnar dislocation. It occurs in both adults and children and is classified based on the direction of dislocation of the radial head and whether only the ulna or both bones are fractured. These fractures are not common and are the most misdiagnosed [1]. Although the diagnosis of these fractures has improved over the years with the help of imaging technology and research, these fractures are difficult to diagnose clinically and can have severe complications if treatment is not done properly. Injuries happen when there is a forceful impact to the forearm while the elbow is straightened and the arm is overly pronated, transmitting pressure through the interosseous membrane, which results in the tearing of the proximal quadrate and annular ligaments, thereby affecting the radiocapitellar joint [2]. Various classifications, Bado classification, Jupiter classification, and Proximal Ulnar and Radial fracture-dislocation Comprehensive Classification System are used to assess the prognosis and the treatment plan for the patients from the choice of fixation, management of head of radius and ligament injuries, including the sequence of surgeries to be done [3]. There are several mentioned complications of Monteggia fractures including the chronic Monteggia, acute or tardy nerve palsies, myositis ossificans, non-union, malunion, recurrent radial head dislocation, and compartment syndrome [4]. However, failure of primary fixation is rarely mentioned. In this article, we discuss four cases that were identified as failures of fixation of the Monteggia fracture dislocation. In all these cases, radial head remained dislocated with malreduction of the ulna and or radius.

Case 1

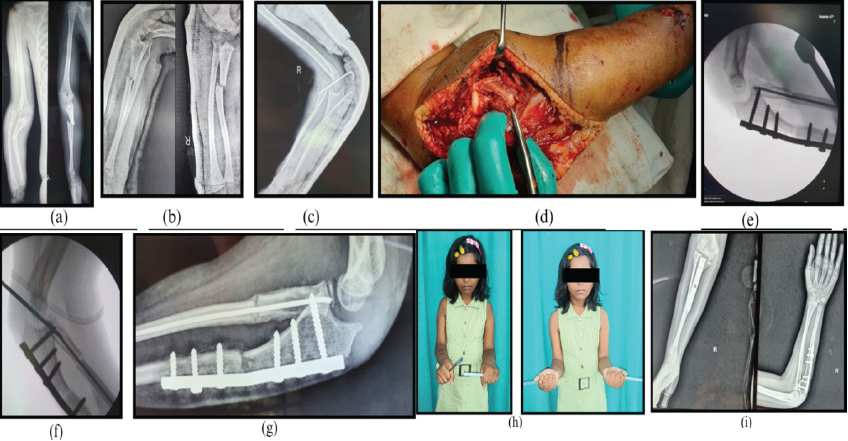

A 6-year-old school-going female child sustained trauma to the right forearm due to a fall on the outstretched hand, resulting in a closed injury in August 2021. Plain radiography of the elbow revealed right proximal ulna and radius fracture with radial head dislocation seen in (Fig. 1a). Although initially thought to be type IV Monteggia fracture, upon close observation, it was seen that the radius was fractured proximal to the ulna. Hence, as per Bado classification, it was diagnosed as a type I equivalent due to the radial head being dislocated anteriorly (Fig. 1b). The patient had a history of soft tissue injury around the elbow a year back, treated with plaster casting. The current fracture was treated within 48 h, where the radial and ulnar fractures were closed reduced and fixed with intramedullary titanium elastic nailing (TENS) system and the radiocapitellar joint was closed reduced and fixed with a K-wire. However, following surgery, it was observed that radiocapitellar joint was dislocated as seen in (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1: (a and b) Plain X-rays of the elbow showing proximal radius and ulna fracture with anterior dislocation of the radial head. As the radius is fractured proximal to the ulna, it is a type I equivalent under the Bado classification. (c) Post-operative X-ray showing persistent dislocation of radial head. (d) A single incision is made to expose both the radial head and the ulna shaft. The posterior interosseous nerve is identified. (e and f) The radio-capitellar joint is fixed to improve the rotational stability of the radius. (g) The wire is removed at 3 weeks, showing a stable joint. (h and i) At 3-year follow-up the elbow is stable, with limited pronation.

Revision plan

The ulna needs rigid fixation to maintain length and control the anterior angulation. As the radius fracture was too proximal to the plate, the nail was retained. The radiocapitellar joint needs to be open reduced and temporarily fixed till the radius fracture gums up.

Surgical steps

The ulna nail was removed. A single skin incision was taken to expose both the radiocapitellar joint and the ulna (Fig. 1d). In this case, the posterior interosseous nerve was identified as the proximal radius was fractured (Fig. 1e). The radiocapitellar joint was reduced. Ulna plating was done with a 3.5 mm dynamic compression plate giving a 10° posterior angulation to it. Just below the proximal physis in the radius, the TENS nail was advanced. Finally, the radiocapitellar joint was fixed with the elbow in 90° with a K-wire (Fig. 1f). With the use of an above-elbow slab, the limb was immobilized in full supination with elevation. The transcapitellar wire was removed at 3-week post-surgery (Fig. 1g). In 2024, at 3-year follow-up, the fracture was well reduced, with the patient having complete flexion at the elbow but with limited pronation (Fig. 1h and i).

The disability of arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) score at the end of 3-year follow-up is 5.8 with a good functional outcome and no difficulty in performing activities of daily living.

Case 2

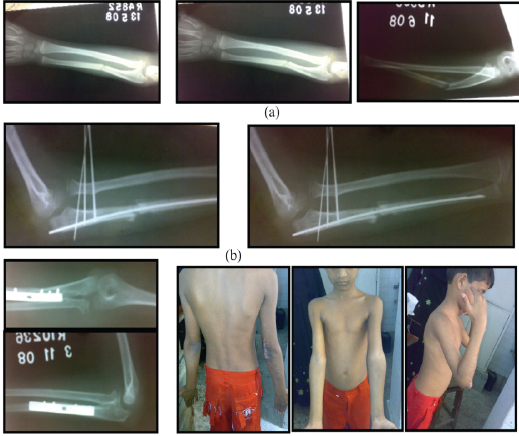

A 7-year-old male child sustained closed trauma to the right forearm due to a fall in May 2008. Plain radiographs showed a fracture of the right proximal ulna with anterior radiocapitellar joint dislocation. The diagnosis was type 1 Monteggia fracture (Fig. 2a). The primary surgeon initially tried to conserve the fracture. After 6 weeks, the patient was taken up for a closed reduction and intramedullary nailing of the ulna. An attempt was made to reduce the radiocapitellar joint by passing three trans-radiocapitellar K-wires from the radius to the ulna. However, this failed to reduce the radiocapitellar joint (Fig. 2b). The patient presented to us 1 week after the index surgery.

Figure 2: (a) Type I Monteggia fracture. (b) Ulna fracture and radio-capitellar joint not reduced. (c) Six months after open reduction and the Bell-Tawse procedure. (d) Range of motion.

Surgical steps

The length and dorsal angulation of the ulna were not maintained. Fortunately, no nerve palsy resulted from the randomly placed K-wires. A second surgery was performed using Speed and Boyd’s (Global posterior) approach to expose the radiocapitellar joint and to fix the ulna. The previous implant was removed, and the ulna was open reduced and fixed using a 3.5 mm dynamic compression plate. The length of ulna was restored with slight dorsal angulation. The radiocapitellar joint was reduced under vision with annular ligament reconstruction using tricipital fascia as it was not stable (the Bell-Tawse procedure). At 6-month follow-up, the reduction was well maintained (Fig. 2c) with functional range of motion (Fig. 2d).

The DASH score at 4-year follow-up is 10.2 with a good functional outcome.

Case 3

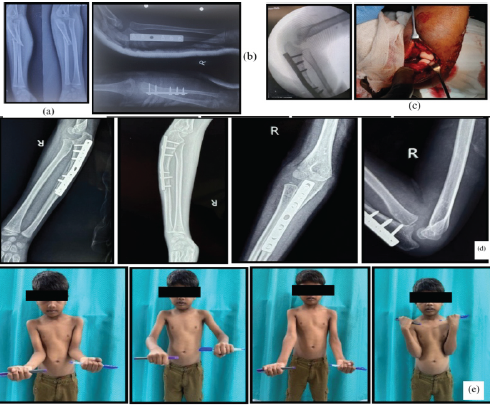

A 6-year-old male patient presented with closed trauma to the right forearm due to a fall from bed in 2024. The radiographs showed a right proximal oblique fracture of the ulna with anterior angulation and dislocation of the radiocapitellar joint. This was a type-1 Monteggia fracture as seen in (Fig. 3a). The patient was operated on the same day in the emergency operating theater with open reduction and rigid ulna fixation with 3.5 mm dynamic compression on the lateral surface of ulna. Intraoperatively, the radiocapitellar joint seemed to have been reduced; however, the post-operative radiograph showed a non-reduced joint (Fig. 3b). It was suspected that either enough tension was not given to the interosseous ligament by improper dorsal angulation to the ulna or that there was soft tissue interposition which hampered the radiocapitellar reduction. A second surgery was thus planned and the ulna plate was repositioned over the dorsal aspect and fixation was done with 15° dorsally angulated 3.5 mm dynamic compression plate to indirectly reduce the radial head. However, the C-arm showed radiocapitellar joint was still dislocated. The radiocapitellar joint was opened through Kocher’s interval. It was observed that the radial head was button holed through the capsule. The obstructing structure was incised, following which the radial head was reduced and stable (Fig. 3c and d).

Figure 3: (a) Type I Monteggia fracture. (b) Radio-capitellar joint still not reduced after ulna plating. (c) Radial head is reduced after incising obstructing tissue. (d and e) Clinical and radiological outcome at 6 months.

In retrospect, there was no need to revise the ulna plating. The surgeon should have opened the radiocapitellar joint instead of revising the ulna plate. Final outcome at 6-month follow-up was excellent (Fig. 3e).

The DASH score at 1-year follow-up is 6.1 with an excellent functional outcome.

Case 4

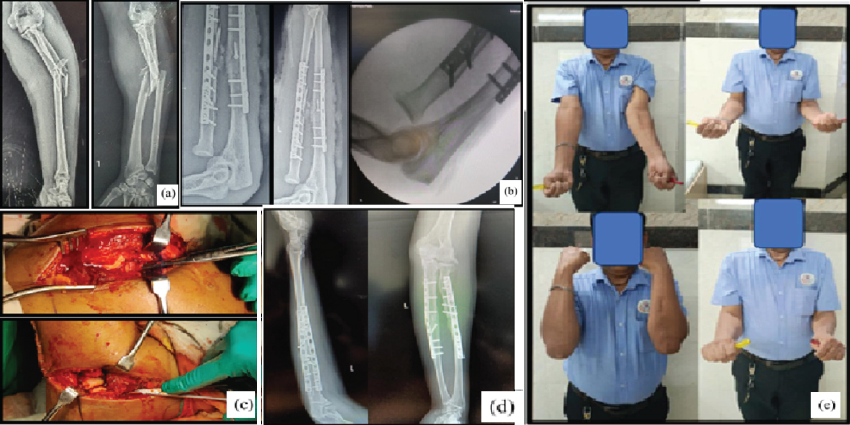

An adult male, 39 years of age, suffered trauma to the left forearm due to a fall from a bike in 2021. Radiographs of the closed injury revealed a comminuted fracture of radius and ulna in the proximal one third, at the same level, with anterior dislocation of radiocapitellar joint and was diagnosed as type IV Monteggia fracture (Fig. 4a).

The case was initially managed with open reduction and rigid fixation of the radius and ulna with 3.5 mm dynamic compression plate. The ulna was approached through the standard subcutaneous border between flexor carpi ulnaris and extensor carpi ulnaris, whereas Henry’s approach was used for the radius. Ulna plating was done over the subcutaneous border, with volar plating for the radius. Despite this, it was observed that the radiocapitellar joint was not reduced (Fig. 4b). Although the bones were fixed rigidly, the bow of the radius was not maintained. The possibility of soft tissue interposition could also have prevented reduction at the radiocapitellar joint. A revision surgery was done within 48 h of surgery, where the original incision was reopened and all implants were removed. Kaplan’s approach for radiocapitellar joint and Henry’s approach for ulna were used. Soft tissue interposition which was preventing the reduction was incised and then the radial head was reduced (Fig. 4c). Radius plating was done over the dorsal-lateral surface to maintain the radial bow and the ulna plate was replaced by a longer 3.5 mm dynamic compression plate and an angulation of about 10° was given. The annular and collateral ligaments were repaired. The radial head was observed to be reduced and stable in pronation and supination. An above-elbow slab was given in full supination for 3-week duration to ensure soft tissue healing at the proximal radio-ulnar joint (Fig. 4d). The Patient now has full range of motion with no instability, though cubitus valgus is seen clinically (Fig. 4e).

Figure 4: (a) Type IV Monteggia fracture. (b) Radio-capitellar joint not reduced in spite of rigid fixation of radius and ulna. (c) Soft tissue obstruction is removed following which radio capitellar joint is reduced and stable. (d) Good reduction after revision of radius plate. (e) Good clinical and radiological outcome with some degree of cubitus valgus.

The DASH score at 3-year follow-up is 6.7 with excellent functional outcome.

The primary goal when it comes to Monteggia fractures, as per the study by Josten et al., is the maintenance of the ulna and radius length, with stable reduction of the radiocapitellar joint while also maintaining the axis and rotation of the ulna [5]. They also summarized in their study that an insufficiently stabilized ulna with soft tissue imposition can cause a persistent radial head subluxation, which was seen in all our cases, warranting a revision surgery [5], though Leonidou et al., have stated that acute Monteggia fractures in pediatric age group can be treated with closed reduction and serial casting procedures [6]. Similarly, Siebenlist et al., stated that open reduction and internal fixation is the standard of care for Monteggia fractures and Monteggia-like fractures, where reconstruction of the anatomy of the ulna with stabilization is paramount for unrestricted elbow function [1]. Zhang et al., in their review states that despite the various treatment modalities available, there are no standard guidelines or protocol for the treatment of Monteggia fractures [7]. A study by Xiao et al., states that adult Monteggia fractures are unstable inherently and multiple revision surgeries should be avoided to improve patient outcomes as they will not help in establishing the alignment of the fractured bones. They also stated that gentle traction lengthens the ulna and realigns the radiocapitellar joint [8]. The persistence of cubitus valgus in our adult patient, in comparison to the other pediatric cases, could also be attributed to the same. Ramski et al., in their study state that acute pediatric Monteggia fractures can have early clinical and radiographic results with minimum instability or late displacement if ulnar fracture pattern-based strategy was used [9]. A meta-analysis by Tan et al., states that in patients who have failed the initial closed reduction, open reduction has to be performed, as seen in our case series, implying adherence to the widely used treatment protocols [10]. However, the reasons for failure of management at the first surgery in all our cases can be attributed to suboptimal fixation with intramedullary nailing of the ulna fracture which in turn does not restore the ulna length, especially in cases of short oblique or comminuted fractures, as ulna nailing is recommended only in transverse fractures. Factors such as Bado type, age, sex, and rate of displacement of radius and ulna could not be proven to be good predictors of treatment failure [9], similar to our cases as well. Other factors include failure to correct the volar angulation of ulna, correct radial bow in cases where the radius is fractured, and failure to open radiocapitellar joint and to address structures preventing the reduction of radiocapitellar joint.

Based on the cases, the authors thus conclude that thorough clinical examination, a proper pre-operative analysis for possible reasons for failure, and proper planning will alleviate the need for revision surgeries and prevent any further complications as seen with these cases.

Despite Monteggia fractures making up <1% of all pediatric forearm fractures, their treatment is fraught with difficulties including missed diagnosis and improper management, making a well-executed treatment plan non-negotiable. A good outcome is assured if forearm fractures are rigidly and anatomically fixed with attention to maintaining both length and angulation, opting to open the radiocapitellar joint without hesitation, when in doubt, and especially in young children with poorly ossified physis, removing soft tissue obstructions and avoiding taking up such cases in an emergency setting.

References

- 1. Siebenlist S, Buchholz A, Braun KF. Fractures of the proximal ulna: Current concepts in surgical management. EFORT Open Rev 2019;4:1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Johnson NP, Silberman M. Monteggia fractures. Medizinische Welt 2023;50:210-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. ElKhouly A, Fairhurst J, Aarvold A. The MonteggiaFracture: literature review and report of a new variant. J Orthop Case Rep 2018;8:78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Soderlund T, Zipperstein J, Athwal GS, Hoekzema N. Monteggia fracture dislocation. J Orthop Trauma 2024;38:S26-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Josten C, Freitag S. Monteggia and Monteggia-like-lesions: Classification, indication, and techniques in operative treatment. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2009;35:296-304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Leonidou A, Pagkalos J, Lepetsos P, Antonis K, Flieger I, Tsiridis E, et al. Pediatric monteggia fractures: A single-center study of the management of 40 patients. J Pediatr Orthop 2012;32:352-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Zhang R, Wang X, Xu J, Kang Q, Hamdy RC. Neglected Monteggia fracture: A review. EFORT Open Rev 2022;7:287-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Xiao RC, Chan JJ, Cirino CM, Kim JM. Surgical management of complex adult monteggia fractures. J Hand Surg Am 2021;46:1006-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Ramski DE, Hennrikus WP, Bae DS, Baldwin KD, Patel NM, Waters PM, et al. Pediatric monteggia fractures: A multicenter examination of treatment strategy and early clinical and radiographic results. J Pediatr Orthop 2015;35:115-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Tan SHS, Low JY, Chen H, Tan JY, Lim AK, Hui JH. Surgical management of missed pediatric monteggia fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2022;36:65-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]