Early recognition of elbow synovial chondromatosis with timely synovectomy and ulnar nerve decompression is key to restoring function and preventing recurrence.

Dr. Anirudh Dwajan, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bilaspur - 174001, Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: anirudhdwajan@gmail.com

Introduction: Primary synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon benign disorder characterized by cartilaginous metaplasia of the synovium, leading to the formation of intra-articular nodules. The elbow joint is an unusual site, and neurological involvement, particularly ulnar nerve compression, is exceptionally rare.

Case Report: A 42-year-old female presented with progressive pain, stiffness, and weakness of grip in her dominant elbow, accompanied by numbness along the ulnar border of the hand. Radiographs revealed a single calcified nodule in the medial compartment of the elbow, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a well-defined intra-articular mass compressing the ulnar nerve. Nerve conduction studies confirmed delayed conduction across the elbow. The patient underwent open excision of the lesion via a medial approach with decompression of the ulnar nerve. Histopathology confirmed primary synovial chondromatosis. At the 6-week follow-up, the patient showed improvement in pain and strength with enhanced ulnar conduction parameters. At 6 months, she regained full motion and complete functional recovery without recurrence.

Conclusion: Solitary synovial chondromatosis of the elbow causing ulnar nerve compression is extremely uncommon. Early diagnosis with MRI and timely surgical decompression can prevent permanent neurological deficits and ensure excellent functional outcomes.

Keywords: Synovial chondromatosis, elbow joint, ulnar nerve compression, primary synovial chondromatosis, synovectomy, case report.

Primary synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon benign condition characterized by cartilaginous metaplasia of the synovium, leading to the formation of intra-articular nodules of hyaline cartilage. These nodules may detach over time, becoming free bodies within the joint cavity, and can subsequently calcify or ossify – a condition referred to as synovial osteochondromatosis [1]. Although its exact pathogenesis remains unclear, cytogenetic studies have identified clonal chromosomal rearrangements involving chromosome 6, supporting a possible neoplastic etiology rather than a purely reactive process [2].

Bell et al. proposed that prior trauma might act as a triggering factor for primary or secondary synovial chondropathy [3]. More recent research, however, suggests that local synovial cells may play an active role in nodule formation. Studies have demonstrated expression of cluster of differentiation markers CD105 and CD90 within the synovial membrane adjacent to cartilaginous nodules, indicating a proliferative or neoplastic component. Furthermore, signaling molecules, such as fibroblast growth factor-2 and transforming growth factor-β3 are thought to promote cartilaginous metaplasia and the development of intra-articular loose bodies, contributing to disease progression [4,5].

The disease most frequently involves the knee joint, followed by the elbow, hip, and shoulder. The elbow is particularly vulnerable because of its complex articulation and exposure to repetitive mechanical stress [6]. Milgram outlined a triphasic-phase progression of the condition:

- Phase I: Active intrasynovial proliferation without loose bodies,

- Phase II: Nodular synovial activity with formation of loose bodies, and

- Phase III: Presence of multiple ossified loose bodies with inactive synovium [7].

Patients often present with pain, swelling, and restriction of movement in the affected joint. Mechanical symptoms, such as locking or clicking may appear as loose bodies enlarge. In rare cases, extension of the lesion may compress adjacent neurovascular structures, leading to neurological deficits, such as paresthesia or weakness [8].

The differential diagnosis includes secondary synovial chondromatosis – a similar process occurring secondary to osteoarthritis, trauma, or osteochondritis dissecans – as well as other conditions, such as synovial chondrosarcoma, pigmented villonodular synovitis, hydroxyapatite deposition disease, tuberculous arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Initial management may involve non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroid injections for symptomatic relief in early disease. However, in progressive or advanced stages, surgical excision of the nodules with partial or total synovectomy remains the treatment of choice. Both open and arthroscopic approaches have been described, with the arthroscopic technique offering quicker rehabilitation and comparable long-term outcomes [9,10].

A woman in her 40’s presented with pain and swelling over the central and medial aspect of her right elbow for 2 months. The pain was dull and persistent, radiating along the forearm and hand. She also complained of numbness and tingling over the ring and little fingers, progressive weakness of grip strength, and mild difficulty in performing daily activities, such as buttoning clothes and holding small objects. There was no preceding trauma, fever, or history suggestive of infection or systemic illness.

She was a known hypertensive for the past 15–16 years, well controlled on medication, with no history of diabetes or tuberculosis.

On local examination, diffuse swelling was noted over the central and medial aspect of the right elbow. The overlying skin was normal, with no redness, warmth, or sinus. A firm, well-defined, non-tender mass was palpable in the cubital fossa on the medial side. The elbow range of motion was restricted, with flexion limited to 100° and incomplete extension. Sensory examination revealed hypoesthesia in the ulnar nerve distribution, particularly over the ring and little fingers. Grip strength was reduced compared to the opposite side, and early clawing of the ulnar two fingers was noted. The radial and ulnar pulses were palpable and normal.

Investigations

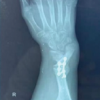

Plain radiographs of the right elbow (anteroposterior and lateral views) demonstrated a soft-tissue density with faint calcific foci over the medial aspect of the joint without evidence of bony erosion or joint-space narrowing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative radiographs of the right elbow showing a single, well-defined calcified nodular opacity in the medial compartment adjacent to the distal humerus – (a) anteroposterior view and (b) lateral view.

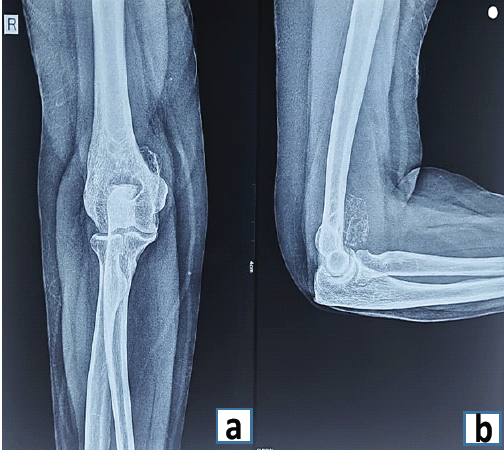

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the right elbow revealed a well-defined periarticular ossified lesion measuring approximately 32 × 18 mm along the distal aspect of the humerus in the cubital fossa. The lesion appeared lobulated and demonstrated low-to-intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequences, consistent with cartilaginous tissue. It was associated with moderate joint effusion and mild synovial thickening, suggestive of synovitis. The adjacent bony structures appeared intact, without cortical erosion or marrow involvement. The lesion was closely related to the ulnar nerve. The overall imaging features were suggestive of primary synovial chondromatosis or synovial osteochondromatosis, with a low likelihood of neoplastic etiology (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Magnetic resonance imaging of the right elbow showing a well-defined periarticular ossified lesion along the distal aspect of the humerus in the cubital fossa, measuring approximately 32 × 18 mm, associated with moderate joint effusion and synovitis. The lesion is seen adjacent to the ulnar nerve without evidence of osseous destruction – features suggestive of synovial osteochondromatosis. (a) Axial T2-weighted image, (b) coronal section, and (c) sagittal section showing the extent and localization of the lesion.

In addition to imaging, a nerve conduction velocity (NCV) study was performed, which demonstrated reduced conduction velocity and prolonged distal latency of the ulnar nerve across the elbow segment, consistent with compressive neuropathy. The median and radial nerves were within normal limits. These findings correlated with the patient’s clinical symptoms and imaging evidence of nerve compression.

These findings were consistent with primary synovial chondromatosis of the elbow presenting with secondary ulnar nerve compression. Routine hematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits.

Treatment

A direct medial approach to the elbow was utilized. After careful dissection, the ulnar nerve was identified and found to be compressed by a firm, nodular mass arising from the synovium near the cubital tunnel. The lesion was encapsulated, measuring approximately 3 × 2 cm, and was located deep to the fascia adjacent to the medial epicondyle.

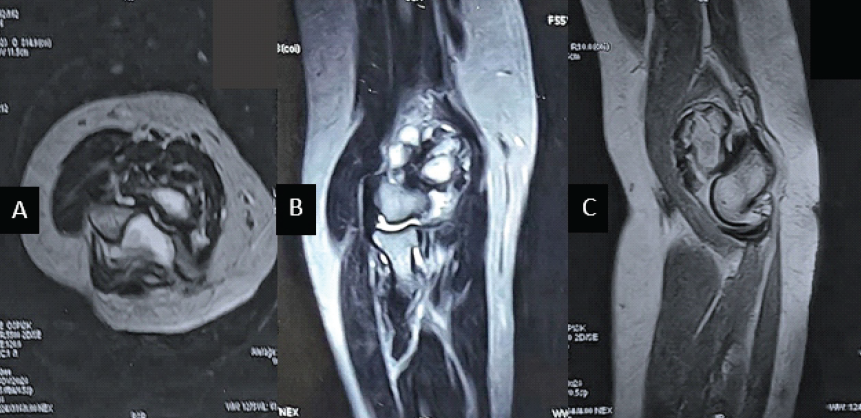

The nerve was gently mobilized and protected throughout the procedure. The mass, along with a cuff of adjacent synovium, was excised in toto and sent for histopathological evaluation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Clinical photograph showing the excised specimen – a single, well-encapsulated nodular mass measuring approximately 3 × 2 cm. A pair of surgical scissors is placed adjacent to the specimen for size reference. The mass appeared firm, smooth-surfaced, and consistent with the gross features of synovial chondromatosis.

Following excision, the ulnar nerve was transposed anteriorly to prevent recurrent compression and was stabilized in a subcutaneous tunnel. Hemostasis was achieved and the wound closed in layers over a suction drain.

Histopathological examination revealed lobules of mature hyaline cartilage with benign-appearing chondrocytes and absence of atypia or mitotic figures, confirming the diagnosis of primary synovial chondromatosis.

Outcome

The post-operative period was uneventful. The patient was started on gentle elbow range-of-motion exercises under physiotherapy supervision from the 1st post-operative day. Analgesics (indomethacin 75 mg twice daily for 5 days) were prescribed for pain control and to reduce post-operative inflammation.

At the 6-week follow-up, she reported marked improvement in pain and numbness along the ulnar border of the hand. Grip strength had improved noticeably, and the early clawing of the ring and little fingers had resolved. The elbow had a painless active range of motion of 0–130°, and there was no residual swelling or tenderness at the operative site. A NCV study performed at this stage demonstrated improved conduction parameters across the ulnar nerve compared with pre-operative values, indicating early neural recovery following decompression.

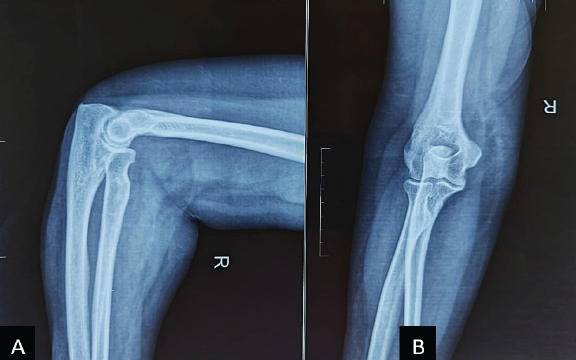

At the 6-month follow-up, the patient maintained her recovery. Radiographs of the right elbow showed complete excision of the previously noted ossified lesion, with no evidence of recurrence, calcified loose bodies, or new periarticular ossification. The joint space and articular margins appeared well preserved, with no degenerative changes or subchondral irregularities (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Six-month post-operative lateral (a) and anteroposterior (b) radiographs of the right elbow showing complete excision of the lesion with well-preserved joint architecture and no evidence of recurrence or periarticular calcification.

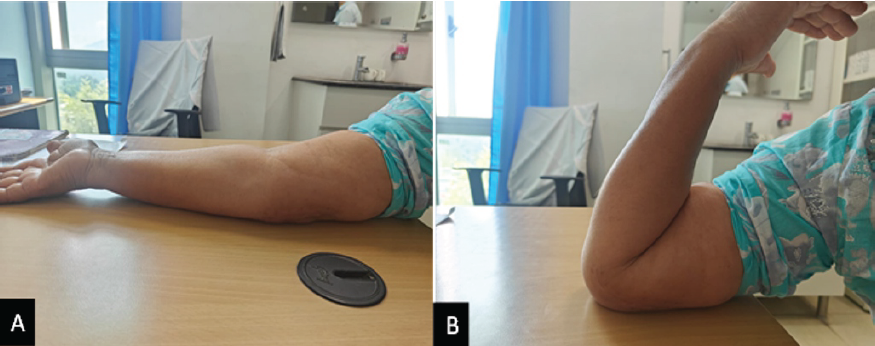

She had no recurrence neurological deficit, and full functional use of the limb was achieved. Elbow motion remained pain-free, and she was able to carry out all household and occupational activities without limitation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Clinical photographs at 6-month follow-up demonstrating full, pain-free range of motion of the right elbow – (a) full extension and (b) flexion – with resolution of pre-operative stiffness and ulnar neuropathic symptoms.

Synovial chondromatosis of the elbow is an uncommon entity and accounts for a small fraction of benign monoarticular pathologies. Although the disease is typically intra-articular, it can occasionally extend to involve the extra-articular tissues or neurovascular structures, resulting in compressive neuropathies [1-8]. In the present case, the patient developed ulnar nerve involvement secondary to a single large cartilaginous nodule located in the medial compartment of the elbow. Such a presentation is distinctly rare, as most reports describe multiple intra-articular loose bodies rather than a solitary lesion causing neurological symptoms [11].

The ulnar nerve is particularly vulnerable at the elbow due to its superficial course in the cubital tunnel. Synovial expansion or a large chondral nodule in this region can lead to chronic compression, manifesting as sensory loss, weakness of intrinsic hand muscles, and impaired grip strength. Only a handful of cases in the literature have documented ulnar nerve compression secondary to synovial chondromatosis, emphasizing its rarity and diagnostic challenge.

MRI remains the most sensitive modality for diagnosis, as it delineates both the cartilaginous and calcified components of the lesion and identifies its relationship to the neurovascular structures. In our patient, MRI revealed a well-defined nodular lesion in close proximity to the ulnar nerve, correlating with the clinical findings of weakness and sensory loss.

The mainstay of treatment is surgical excision of the cartilaginous nodule with decompression of the involved nerve. In this case, a direct medial approach to the elbow allowed adequate exposure for complete excision of the mass and meticulous ulnar nerve decompression. The lesion was removed en bloc, preventing recurrence from residual disease. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of primary synovial chondromatosis, excluding secondary causes and malignant transformation [12,13,14].

Post-operatively, the patient demonstrated marked symptomatic relief with gradual return of motor function and improvement in grip strength. At the 6-week follow-up, NCV testing revealed significant improvement in ulnar nerve function, though not complete normalization. By 6 months, the patient achieved full, pain-free range of motion with near-complete sensory recovery and no radiological evidence of recurrence.

The overall prognosis after complete excision is excellent; however, recurrence rates up to 20–25% have been reported, particularly in cases with incomplete synovectomy or residual nodules. Long-term follow-up is therefore essential to identify early recurrence or malignant transformation into synovial chondrosarcoma, although such progression remains extremely rare [15].

This case is notable because of its atypical presentation with a solitary intra-articular nodule causing compressive neuropathy, rather than the classical multiple loose bodies. Early surgical intervention led to satisfactory neurological recovery and functional restoration of the elbow joint.

Synovial chondromatosis of the elbow is an uncommon benign condition that can occasionally present with compressive neuropathy when the proliferative synovium or cartilaginous nodules extend near neurovascular structures. Although most cases involve multiple intra-articular bodies, a solitary nodule causing ulnar nerve compression is distinctly rare. Early recognition of this presentation and timely surgical excision can prevent permanent neurological deficits and restore joint mobility. MRI remains the investigation of choice for diagnosis and surgical planning, while long-term follow-up is essential to monitor for recurrence.

Synovial chondromatosis, though a benign condition, can occasionally present in unusual ways, such as compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve, particularly when the lesion arises near the medial elbow. Even a solitary nodule can produce significant neurological symptoms and functional limitation. Awareness of this rare presentation and early surgical intervention are crucial to prevent permanent nerve damage and to achieve excellent recovery of motion and function.

References

- 1. Kamineni S, O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Synovial osteochondromatosis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:961-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Buddingh EP, Krallman P, Neff JR, Nelson M, Liu J, Bridge JA. Chromosome 6 abnormalities are recurrent in synovial chondromatosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2003;140:18-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Bell G, Sharp CW, Fourie LR, Hutchinson D. Conservative surgical management of synovial chondromatosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997;84:592-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Wake S, Yoshitake H, Kayamori K, Izumo T, Harada K. Expression of CD90 decreases with progression of synovial chondromatosis in the temporomandibular joint. Cranio 2016;34:250-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Li Y, El Mozen LA, Cai H, Fang W, Meng Q, Li J, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 3 involved in the pathogenesis of synovial chondromatosis of temporomandibular joint. Sci Rep 2015;5:8843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Patted SM, Kyalakond HK, Aurad R. Synovial chondromatosis of elbow in an adolescent girl: An uncommon site in an uncommon age group-a case report. J Orthop Rep 2024;3:100343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: A histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:792-801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Mo J, Pan J, Liu Y, Feng W, Li B, Luo K, et al. Bilateral synovial chondromatosis of the elbow in an adolescent: A case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020;21:377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Roy M, Das D, Shahare P, Dwidmuthe S, Chandrakar D. Management of synovial chondromatosis of the elbow with ulnar nerve palsy by open approach: A case report. Cureus 2024;16:e59807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Zhu W, Wang W, Mao X, Chen Y. Arthroscopic management of elbow synovial chondromatosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Muramatsu K, Miyoshi T, Moriya A, Onaka H, Shigetomi M, Nakashima D, et al. Extremely rare synovial chondrosarcoma arising from the elbow joint: Case report and review of the literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21:e7-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Narasimhan R, Kennedy S, Tewari S, Dhingra D, Zardawi I. Synovial chondromatosis of the elbow in a child. Indian J Orthop 2011;45:181-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. De Smet L. Synovial chondromatosis of the elbow presenting as a soft tissue tumour. Clin Rheumatol 2002;21:403-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Sachinis NP, Sinopidis C, Baliaka A, Givissis P. Odyssey of an elbow synovial chondromatosis. Orthopedics 2015;38:e62-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. McCarthy C, Anderson WJ, Vlychou M, Inagaki Y, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, et al. Primary synovial chondromatosis: A reassessment of malignant potential in 155 cases. Skeletal Radiol 2016;45:755-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]