Even in properly reduced pediatric both-bone forearm fractures, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for median nerve entrapment when neurological symptoms persist or develop post-reduction. Early recognition and timely decompression are essential to prevent long-term functional deficits.

Dr. Joshua Lyndon Dale, William Carey College of Osteopathic Medicine, 710 William Carey Parkway Hattiesburg - 39401, Mississippi, United States. E-mail: joshuadaledo@gmail.com

Introduction: Both-bone forearm fractures are common in pediatric patients and most often result from a fall onto an outstretched hand. Although rare, nerve entrapments, particularly of the median nerve, can occur, especially following closed reduction.

Case Report: We present the case of a 13-year-old male who sustained a both-bone forearm fracture while on vacation in Mexico. The injury was managed with closed reduction and casting. Despite appropriate treatment, the patient developed progressive numbness, tingling, and thenar atrophy in the median nerve distribution. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies confirmed significant median nerve dysfunction. Surgical exploration revealed the median nerve entrapped in dense scar tissue with an hourglass deformity approximately 18 cm proximal to the wrist. The patient underwent successful median nerve neurolysis and open carpal tunnel release. Postoperatively, he experienced steady neurological recovery, with full restoration of motor and sensory function by the 8-month follow-up. This case is notable for the delayed onset of median nerve entrapment symptoms despite proper fracture alignment and management. It highlights the potential for dense periosteal scarring to cause nerve compression even in the absence of radiographic abnormalities. Comparison with similar cases in the literature emphasizes the importance of early recognition and timely surgical intervention.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for nerve entrapment in pediatric both-bone fractures, even when reduction appears satisfactory. Early diagnosis and surgical decompression are crucial to prevent long-term functional deficits.

Keywords: Orthopedics, pediatric, both-bone forearm fracture, median nerve entrapment, neurolysis, carpal tunnel release.

Both-bone fractures involve concurrent fractures of the radius and ulna and account for 3–6% of pediatric fractures, with peak incidence between 10 and 14 years of age [1,2]. The most common mechanism is a fall onto an outstretched hand [3]. Nerve injuries following forearm fractures are rare, but when they occur, the median nerve is most commonly affected [4]. Entrapment neuropathies result from compression or irritation of peripheral nerves as they pass through anatomically constrained spaces [5,6]. The median nerve may be compressed at several sites, including the ligament of Struthers, pronator teres, flexor digitorum superficialis arch, and carpal tunnel [6]. We present the case of a 13-year-old male who developed symptoms of median nerve entrapment 4 months after treatment of a both-bone forearm fracture. The patient reported visiting a hospital in Mexico, where an attempt was made to reduce the fracture. Despite undergoing closed reduction, the patient began to experience median nerve symptoms several months after the initial injury. This case is notable due to the delayed presentation of median nerve entrapment despite prior fracture management. Given the patient’s symptoms and the severity of his condition, we opted to proceed with median nerve neurolysis and carpal tunnel release.

We present a case of delayed median nerve entrapment in a 13-year-old male following a properly reduced both-bone forearm fracture. This case emphasizes the need for vigilance in detecting neurological complications even after seemingly uncomplicated fracture management.

A 13-year-old male presented to the clinic with complaints of numbness and tingling in the median nerve distribution. He was referred to our clinic by his primary care provider due to concerns regarding inadequate recovery following a previous both-bone forearm fracture. The patient reported that while in Mexico, he sustained a both-bone forearm fracture after a fall he sought medical care at a local hospital, where he underwent closed reduction and cast application immediately after the injury, 4 months prior. Following the cast application, the patient experienced severe pain in the forearm for the first 3 days, which eventually subsided and evolved into the present symptoms of numbness and tingling. Six weeks after the injury, the cast was removed; however, the median nerve symptoms persisted. The patient expressed concern about progressive muscle wasting in both the hand and forearm. Following cast removal, he pursued physical therapy for 1 month, but reported that it exacerbated his symptoms rather than providing relief. On physical examination, the patient appeared well and was in no acute distress. Examination of the left hand and forearm revealed thenar atrophy and decreased muscle mass within the forearm. Thenar and forearm atrophy presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Patients’ left and right arms. Arrows pointing toward the forearm and thenar atrophy.

The patient retained full passive range of motion (ROM) of the fingers, with no evidence of contractures. A positive Tinel’s sign was observed over the median nerve in the mid-forearm, extending to the carpal tunnel, which localized distally to the median nerve. Strength testing demonstrated weakness of the flexor digitorum profundus and flexor pollicis longus. Sensory testing revealed two-point discrimination >15 mm in the median nerve distribution and 4 mm in the ulnar nerve distribution.

Radiographic evaluation of the left forearm showed a healed both-bone forearm fracture with good alignment (Fig. 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Lateral view X-ray demonstrating well healing both bones.

Figure 3: Anterior-posterior X-ray demonstrating well healing both bone fractures.

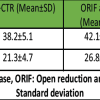

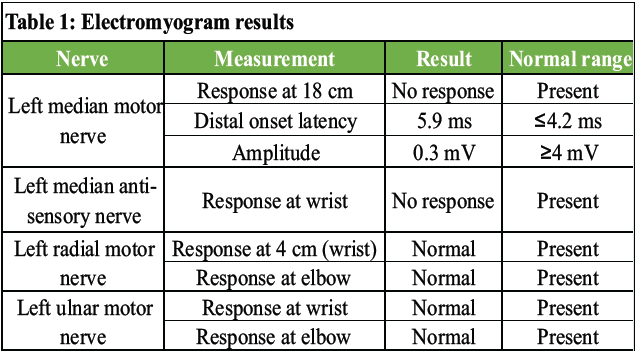

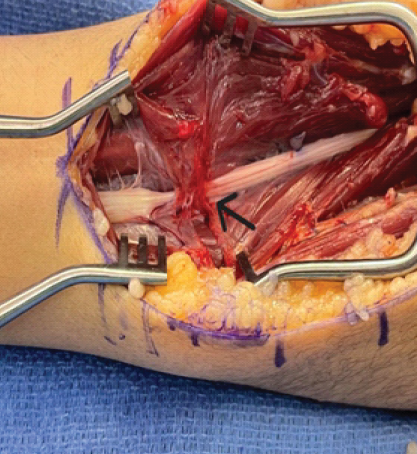

Given the patient’s neurological findings, we proceeded with electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies to localize the point of compression in the forearm. The EMG revealed that the left median motor nerve showed no response at 18 cm, with prolonged distal onset latency (5.9 ms) and reduced amplitude (0.3 mV). In addition, the left median anti-sensory nerve showed no response at the wrist. The left abductor pollicis brevis muscle demonstrated increased insertional activity, moderately increased spontaneous activity, diminished recruitment, and significantly decreased interference patterns.

Testing of the left radial motor nerve at the wrist (4 cm) and elbow, as well as the left ulnar motor nerve at the wrist and elbow, showed normal responses. All other tested muscles showed no evidence of electrical instability. These findings are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1: Electromyogram results

Table 2: Needle testing results

Although X-ray imaging did not reveal any apparent abnormalities, we decided to proceed with left forearm median nerve decompression based on the results of the patient’s EMG and needle testing. We informed the patient that the procedure would involve two operative steps: A left open carpal tunnel release and a left median nerve neurolysis in the mid-forearm. The patient and his family were thoroughly counseled about the potential risks and complications associated with these surgeries, and they agreed to proceed. Given the unique nature of this case, we obtained verbal consent from the patient and his family to generate this case report.

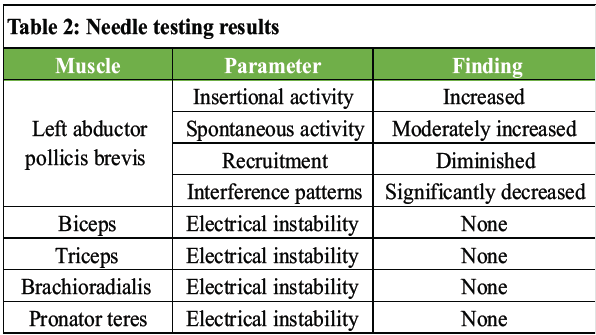

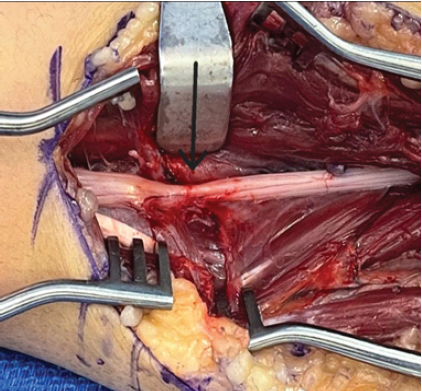

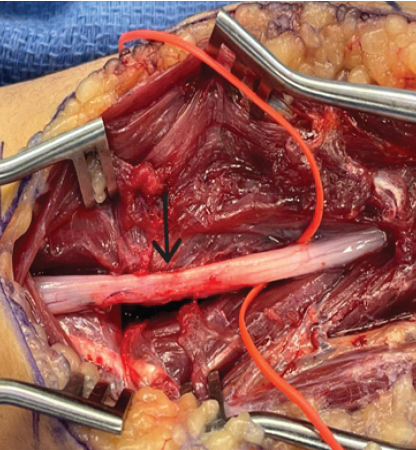

After performing the time-out, we initially focused on the carpal tunnel, aiming to release all potential points of compression along the median nerve. After decompressing the carpal tunnel, we directed our attention to the forearm. We targeted the area 18 cm proximally, where the EMG indicated the point of compression, as well as the location of the Tinel’s sign in the forearm, approximately 10 cm proximal to the wrist crease. During dissection, we encountered a region of dense scar tissue at the previous fracture site. The median nerve appeared highly compressed with an hourglass deformity, as demonstrated in Fig. 4, 5, 6. Upon closer inspection, the nerve was found to be adhered to the bone. Using loupe magnification, we carefully removed the periosteum. Once the nerve was mobilized, we opened the epineurium and resected the scarred epineurium and periosteum, allowing for effective decompression of the nerve. To minimize the risk of adhesion formation, we placed an amniotic membrane wrap between the bone and the nerve. The patient’s surgery was completed without complications and was told to follow a non-weight-bearing status until the 2-week follow-up.

Figure 4: Median nerve compressed with adhesion.

Figure 5: Median nerve with adhesions removed, still attached, arrow pointing toward the hourglass shape.

Figure 6: Nerve successfully mobilized.

The surgery was successful as the median nerve was liberated from its entrapment. The patient returned for follow-up visits at 2 weeks, 2 months, and 8 months post-operatively. At the 2-week follow-up, we removed the protective wrap from the forearm and wrist (Figs. 5 and 6). The patient reported being pain-free, and the Tinel’s sign over the median nerve had improved, now presenting at 6 cm proximal to the palmar crease compared to 18 cm before surgery.

At the 2-month follow-up, the patient reported increased sensation in the thumb, although some residual tingling and numbness persisted in the index and middle fingers. On examination, the patient could make a fist without discomfort, and the Tinel’s sign remained slightly positive over the median nerve along the forearm. At the 8-month follow-up, the patient reported that sensation in the thumb was almost normal, and the preoperative paresthesia had resolved. In addition, the patient demonstrated a full ROM of the wrist and fingers, with no Tinel’s sign and complete resolution of thenar atrophy.

Median nerve entrapment following pediatric both-bone forearm fractures is rare, with fewer than 20 cases reported [7,8]. Although transient neurapraxia is common post-fracture, persistent or delayed deficits may indicate true entrapment. Delayed entrapment, as in this case, often results from periosteal fibrosis or excessive scar formation rather than direct fracture interposition [4,5,7]. During fracture healing, fibroblasts create a collagen matrix to replace granulation tissue. Excessive fibroblast activity or dysregulated periosteal repair can lead to dense scarring capable of entrapping adjacent neurovascular structures [9,10]. In our patient, a dense periosteal scar produced an hourglass deformity of the median nerve approximately 18 cm proximal to the wrist. Unlike cases with acute entrapment at the fracture site [8], the delayed presentation underscores the need for ongoing neurovascular monitoring. Previous reports demonstrate variable presentations and outcomes. Fourati et al. [7] described delayed median neuropathy 3 months after closed reduction, whereas Hurst and Aldridge [8] reported acute entrapment at the time of fracture, successfully treated with immediate surgery. Hutchison and Wester [5] reported median nerve incarceration within the ulna despite well-aligned fractures. These cases emphasize that radiographic alignment does not exclude entrapment.

Distinguishing neurapraxia from true entrapment is essential. Progressive weakness, muscle atrophy, and abnormal EMG findings necessitate surgical exploration [6,7,8]. Pediatric patients retain excellent neuroplasticity, and even delayed decompression may achieve full recovery. Microsurgical neurolysis, careful epineurial release, and anti-adhesion measures (e.g., amniotic membrane wrap) optimize outcomes [4,9]. This case reinforces key lessons: Persistent neuropathic symptoms after closed reduction warrant thorough evaluation, including electrodiagnostic studies. Early recognition and surgical intervention prevent long-term deficits and optimize functional recovery in pediatric patients.

Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for nerve entrapment in pediatric both-bone forearm fractures, even after successful reduction. Delayed neurological symptoms should prompt careful assessment and electrodiagnostic evaluation. Early decompression is critical to restoring function and preventing permanent deficits. This case highlights the importance of continued neurological follow-up and awareness of rare complications in pediatric forearm fractures.

Both orthopedic surgeons and general practitioners must remain vigilant for nerve entrapment following closed reductions, particularly in pediatric both-bone forearm fractures. Prompt recognition and timely surgical intervention facilitate optimal recovery.

References

- 1. Sinikumpu JJ, Lautamo A, Pokka T, Serlo W. The increasing incidence of paediatric diaphyseal both-bone forearm fractures and their internal fixation during the last decade. Injury 2012;43:362-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Vopat ML, Kane PM, Christino MA, Truntzer J, McClure P, Katarincic J, et al. Treatment of diaphyseal forearm fractures in children. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2014;6:5325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Alrashedan BS, Jawadi AH, Alsayegh SO, Alshugair IF, Alblaihi M, Jawadi TA, et al. Patterns of paediatric forearm fractures at a level I trauma centre in KSA. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2018;13:327-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Padovano WM, Dengler J, Patterson MM, Yee A, Snyder-Warwick AK, Wood MD, et al. Incidence of nerve injury after extremity trauma in the United States. Hand (N Y) 2022;17:615-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: A contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep 2020;5:e829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Wertsch JJ, Melvin J. Median nerve anatomy and entrapment syndromes: A review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1982;63:623-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Fourati A, Ghorbel I, Karra A, Elleuch MH, Ennouri K. Median nerve entrapment in a callus fracture following a pediatric both-bone forearm fracture: A case report and literature review. Arch Plast Surg 2019;46:171-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hurst JM, Aldridge JM 3rd. Median nerve entrapment in a pediatric both-bone forearm fracture: Recognition and management in the acute setting. J Surg Orthop Adv 2006;15:214-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Wang H, Qi LL, Shema C, Jiang KY, Ren P, Wang H, et al. Advances in the role and mechanism of fibroblasts in fracture healing. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024;15:1350958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Liu YL, Tang XT, Shu HS, Zou W, Zhou BO. Fibrous periosteum repairs bone fracture and maintains the healed bone throughout mouse adulthood. Dev Cell 2024;59:1192-209.e6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]