Patients with ankylosing spondylitis are at increased risk for injury during surgery and positioning due to stiff and brittle spines, and therefore, special care should be taken to limit stresses placed on the spine.

Mr. Mathieu Holt, 3000 Arlington Ave, Toledo, OH 43614. E-mail: mathieu.holt@rockets.utoledo.edu

Introduction: Patients with stiff and brittle spines, such as those with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), are at an increased risk of intraoperative and post-operative complications. Specifically, patients with AS who undergo total hip arthroplasty (THA) with a direct anterior approach are at risk for vertebral fractures due to patient positioning and manipulation necessary to utilize this approach. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second publication discussing vertebral fracture following THA with direct anterior approach and the first depicting a hyperextension fracture.

Case Report: A 78-year-old male with previous medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, AS, chronic back pain, and non-union left acetabular fracture and post-traumatic arthritis following a fall and subsequent open reduction and internal fixation presented for THA. The patient did not complain of back pain preoperatively. On post-operative day (POD) 1 he began complaining of back pain when ambulating. On POD 3, he complained of acute on chronic exacerbation of back pain, and computed tomography at that time was significant for unstable L2 hyperextension fracture necessitating T12-L4 fusion.

Conclusion: Patients with a history of AS are at increased risk for vertebral fractures when having THA with a direct anterior approach. This approach subjects patients to extension forces that may cause damage to their vertebrae. Due to this risk, physicians should take care when planning their method for THA in this population and consider using alternative approaches or be more mindful of the patient’s condition when positioning them intraoperatively.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, spine, fracture, hip, ankylosing spondylitis.

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) have a risk of spinal fracture up to four times greater than the general population [1]. These patients also have up to a one-and-a-half times greater risk for hip fracture than the general population, which occurs on average 5 years younger than the general population [2]. AS results in a rigid spine that is more susceptible to fracture in the setting of trauma and excessive manipulation, which may occur in surgery [3]. Patients with stiff spine conditions (such as AS and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis) often have delayed diagnosis of thoracolumbar fractures, ranging from 15 to 41% of fractures [4]. This paper describes a 78-year-old male patient with AS who underwent a total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to acetabular fracture open reduction, and internal fixation (ORIF) non-union. This THA used a direct anterior approach; the surgery was tolerated by the patient well and proceeded without complication. The patient experienced exacerbation of chronic low back pain on post-operative day (POD) 3 after a computed tomography (CT) scan and was diagnosed with an acute unstable hyperextension fracture of L2 vertebral body that was subsequently treated with spinal decompression and fusion. To the best of our knowledge, only one other publication describes a vertebral fracture following THA in a patient with AS, the purpose of this article is to report specifically a hyperextension fracture as a novel complication and add to the existing literature of vertebral fracture following THA in this population.

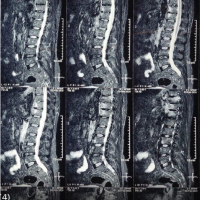

A 78-year-old male with previous medical history of rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, and AS presented for left THA due to non-union of ORIF of left acetabular fracture secondary to fall off of a ladder and post-traumatic arthritis. The patient had a pelvic X-ray significant for acute comminuted fracture of the left acetabulum with post-traumatic protrusion deformity that resulted in subsequent ORIF of left acetabulum over a year before the THA; pre-operative CT abdomen and pelvis and post-operative X-ray abdomen was not significant for vertebral fracture at this time (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (Top left) pre-operative coronal computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis significant for left acetabulum fracture and negative for lumbar fracture. (Top right) pre-operative sagittal CT abdomen and pelvis negative for lumbar fracture. (Bottom left) anterior-posterior (AP) X-ray film significant for left acetabulum fracture before open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). (Bottom right) AP X-ray 1 week s/p ORIF of left acetabulum fracture, significant for lumbar vertebral degenerative changes and negative for lumbar fracture.

In the interval he had residual pain, limb-length discrepancy, weakness of left lower extremity, hip flexion contracture, low back pain, and foot drop. Neurosensory examination and films taken in the interval and in the pre-operative period were consistent with initial findings and significant for non-union of the left acetabular fracture. 14 months s/p ORIF X-ray was significant for non-union of acetabular fracture (Fig. 2), no imaging was taken in the interval to assess for lumbar pathology.

Figure 2: Anterior-posterior X-ray film significant for left acetabular non-union 14 months s/p open reduction and internal fixation.

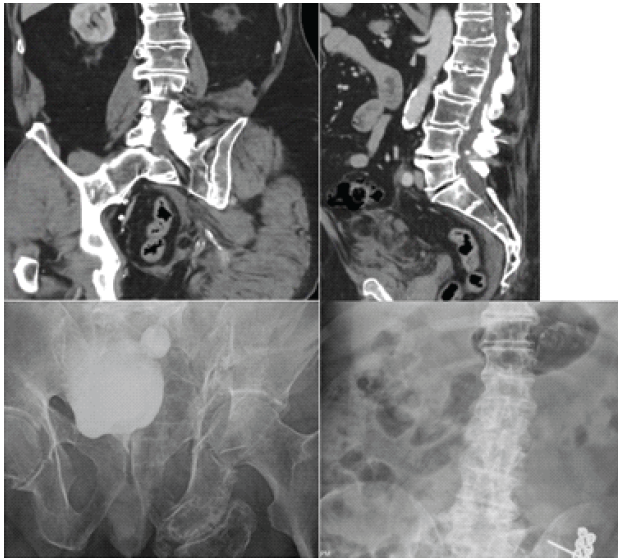

The THA was conducted with an anterior approach with the use of a table and pegboard in the lateral position without complication. Intraoperative observations included severe hip degenerative changes with severe osteophytes, heterotopic ossification (HO) that required partial excision, and persistent acetabulum fracture union with anterior column defect. The patient received cancellous bone allograft and acetabular screws for fixation of the acetabular fracture non-union, as well as a non-cemented acetabular shell, constrained femoral head, and non-cemented femoral implant. The patient had post-operative pain and hematoma on POD 0, and he did not ambulate. Pain and hematoma on POD 1 and 2 were significant; the patient also began to ambulate with a walker on POD 1. On POD 3, the patient received a CT and afterward complained of acute atraumatic exacerbation of chronic low back pain. CT was significant for acute appearing hyperextension fracture of the L2 vertebral body with paravertebral hematoma (Fig. 3), likely sustained during hyperextension of the hip and spine intraoperatively to improve anterior hip access. The patient was placed on strict bed rest on POD 4 due to CT findings.

Figure 3: (Left) Coronal computed tomography (CT) significant for L2 hyperextension fracture. (Right) Sagittal CT significant for L2 hyperextension fracture.

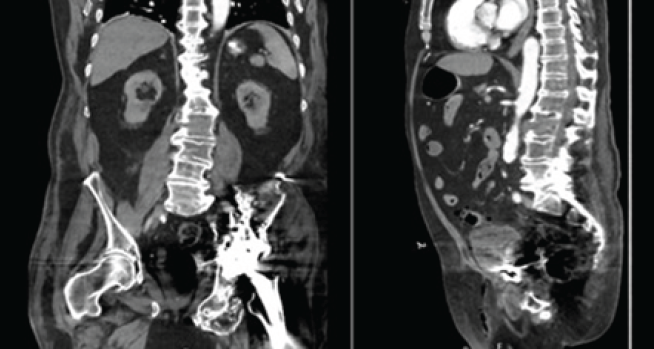

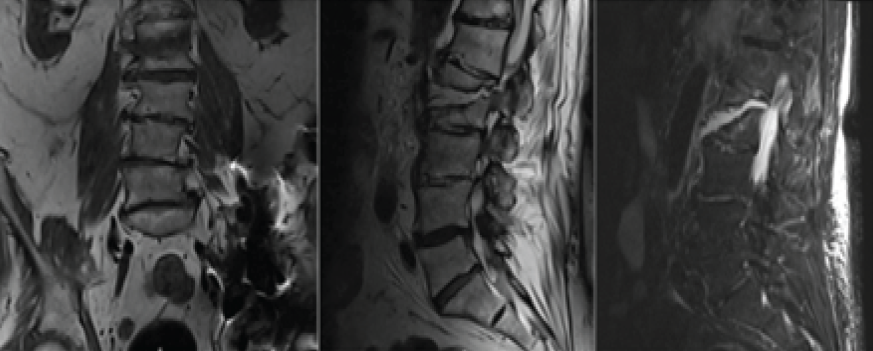

Magnetic resonance imaging on POD 5 was additionally significant for L1-L2 severe right sided neural foraminal narrowing secondary to distracted fragment of L2, at which point the patient was diagnosed with unstable L2 hyperextension fracture and neurosurgery was consulted (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: (Left) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) significant for L2 hyperextension fracture. (Middle) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI significant for L2 hyperextension fracture. (Right) Sagittal short tau inversion recovery weighted MRI significant for L2 hyperextension fracture.

On POD 6 the patient returned to the operating room for percutaneous posterolateral fusion of T12-L4 vertebrae and tolerated this operation well (Fig. 5). The patient discharged to inpatient rehabilitation on POD 8 from THA.

Figure 5: Anterior-posterior X-ray s/p lumbar spine fusion and left total hip arthroplasty.

This case presents a patient with AS who was found to have an unstable L2 hyperextension fracture after THA using a direct anterior approach. This patient had known AS without neurologic deficits. It remains unclear when this fracture occurred or what contributed to its cause. We have hypothesized that manipulation of the patient during anesthesia and during the THA could have subjected the spine to extension forces and contributed to the fracture. We also hypothesize that movement and manipulation as part of the post-operative therapy and imaging processes could have subjected his spine to extension forces and contributed. The patient’s CT scan was significant for an incidental vertebral fracture finding. Patients with AS who receive primary THA have a rare infection, mechanical, and revision complication rate (<1%) in the perioperative and 30-day period that is comparable to rates in the general population [5]. Previous studies have suggested that patients with AS have a higher complication rate than the general public, but those studies had not adjusted for shared comorbidities known to increase complication rates before making comparisons [5,6,7]. The 19-day period mortality rate is lower among patients with AS for primary THA when compared to the general population after adjusting for comorbidities (0.36% vs. 0.7%) regarding infectious and mechanical complications requiring revision [5]. When accommodating comorbidities in comparison, patients with AS tolerate THA well with perioperative complication rates similar to the general population. Patients with AS have an increased risk of HO and hip dislocation after THA when compared to the general population. HO is a trauma and surgery-related complication in which bone deposits occur in tissues such as tendons, ligaments, and other soft tissues that can lead to increased pain and decreased range of motion. Patients with AS have been observed to have increased rates of HO when compared to the general population, although further exploration of this relationship has been recommended [8]. Chung et al. report that patients with AS have a higher rate of dislocation than the control group for patients age >70 years at all-time points through a 5-year follow-up after THA with an odds ratio of 1.75–2.09, P < 0.05. They theorize that the cause of this statistically significant difference is due to the decreased spinopelvic motion in the sagittal plane common in patients with AS. Chung et al. report a difference in dislocation-free survivorship between these groups (95.7% (95% CI, 94.5–96.9%) compared to 97.3% (95% CI, 96.6–98.0%), although it is notable that there is not a statistical difference in their data at a 95% confidence interval [9]. Of note, increased rates of dislocation after THA are found in other populations with decreased spinal mobility, such as those with spinal and spinopelvic fusion. Buckland et al. report increasing rates of hip dislocation after THA corresponding to the number of levels fused (2.96% for 1–2 levels, 4.12% for levels 3–7, P < 0.0001) when compared to controls [10]. Bedard et al. conducted a review of the Humana database and found a relative risk of 2.9 for patients with a history of THA and spinopelvic fusion to experience a dislocation relative to patients without a history of spinopelvic fusion [11]. Rarely, patients with AS have reported complications of hyperextension fractures. These fractures have necessitated spinal decompression and fusion due to instability and neurologic symptoms such as pain, numbness, and weakness in the lower extremities [3]. Specifically, patients with AS who have a kyphotic deformity appear to be at a higher risk of vertebral fracture with neurologic complication [3,12]. Surgeons performing THA on patients with AS should maintain a high index of suspicion for iatrogenic vertebral fracture in patients with increased low back pain and neurologic deficits in the perioperative period, and attempt to reduce spinal hyperextension in the perioperative period.

Patients with conditions decreasing spinal mobility, such as AS and spinopelvic fusion, have increased complication rates after THA compared to the general population. Specifically, patients with AS have an increased risk for vertebral fracture, prosthesis dislocation, and HO. This case adds to the existing literature of AS patients reporting hyperextension fracture after receiving THA with the direct anterior approach. While any approach for THA can place a patient at risk for complication, the direct anterior approach includes extension of the hip and anterior pelvic tilt that subjects the non-flexible lumbar spine to an extension-distraction force associated with unstable hyperextension fractures. Surgeons should consider different approaches or take special care when manipulating the patient during a direct anterior approach to avoid excessive extension of the hip and back. In addition, surgeons should consider lumbar spine imaging after THA for early detection of iatrogenic lumbar fractures.

Surgeons performing THA on patients with AS should consider multiple approaches and/or be mindful of the forces applied to a patient’s spine when using the direct anterior approach. With this awareness, surgeons should attempt to mitigate these forces when possible and consider early post-operative evaluation of the patient’s spine.

References

- 1. Chaudhary SB, Hullinger H, Vives MJ. Management of acute spinal fractures in ankylosing spondylitis. ISRN Rheumatol 2011;2011:150484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Tsur AM, David P, Watad A, Nissan D, Cohen AD, Amital H. Ankylosing spondylitis and the risk of hip fractures: A matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2022;37:3283-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Pitta M, Wallach CJ, Bauk C, Hamilton WG. Lumbar chance fracture after direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today 2017;3:247-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Bereźniak M, Piłat K, Niwiński J, Świątkowski J, Byrdy-Daca M, Łęgosz P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of plain films in detection of thoracolumbar fractures in minor trauma patients: Comparison with CT. Pol J Radiol 2025;90:e260-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Ward MM. Complications of total hip arthroplasty in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:1101-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Blizzard DJ, Penrose CT, Sheets CZ, Seyler TM, Bolognesi MP, Brown CR. Ankylosing spondylitis increases perioperative and postoperative complications after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:2474-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Trent G, Armstrong GW, O’Neil J. Thoracolumbar fractures in ankylosing spondylitis. High-risk injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;227:61-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Anaspure O, Newsom A, Patel S, Baumann AN, Eachempati KK, Smith W, et al. Postoperative complications rates and outcomes following total hip arthroplasty in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review. J Orthop 2025;69:86-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chung BC, Stefl M, Kang HP, Hah RJ, Wang JC, Dorr LD, et al. Increased dislocation rates following total hip arthroplasty in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Hip Int 2023;33:1026-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Buckland AJ, Puvanesarajah V, Vigdorchik J, Schwarzkopf R, Jain A, Klineberg EO, et al. Dislocation of a primary total hip arthroplasty is more common in patients with a lumbar spinal fusion. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:585-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bedard NA, Martin CT, Slaven SE, Pugely AJ, Mendoza-Lattes SA, Callaghan JJ. Abnormally high dislocation rates of total hip arthroplasty after spinal deformity surgery. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2884-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Schnaser EA, Browne JA, Padgett DE, Figgie MP, D’Apuzzo MR. Perioperative complications in patients with inflammatory arthropathy undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2286-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]