Revision total hip replacement in young patients with complex acetabular defects, particularly following childhood hip trauma, requires a staged surgical approach combined with advanced imaging and patient-specific 3D-printed implants to achieve improved implant fit, stability, and early functional outcomes, highlighting the importance of personalized reconstructive strategies in managing challenging revision scenarios.

Dr. J S R G Saran, Department of Orthopaedics, M S Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences, M S R Nagar, New B E L road, Bengaluru 560054, Karnataka, India. E-mail: jsaran868@gmail.com

Introduction: Revision total hip replacement (THR) in young patients is challenging due to higher functional demands, altered anatomy from prior pathology, and increased risk of implant failure. Severe acetabular bone loss, especially following childhood hip trauma and previous reconstruction, further complicates revision procedures. Advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing now enable patient-specific implants that improve implant fit, stability, and surgical precision.

Case Report: A 36-year-old female with a history of childhood hip trauma and a left THR performed 4 years earlier presented with progressive hip pain and functional decline following a fall. Examination revealed Trendelenburg gait, painful global restriction of hip movements, joint line tenderness, and limb length discrepancy. Radiographs showed superior migration and failure of the acetabular component and metal augment. Metal artifact reduction system computed tomography (CT) demonstrated extensive superolateral and medial pelvic bone loss. A staged revision was planned. Stage one involved implant removal and placement of a cement spacer. Repeat 3D reconstruction CT was used to generate a patient-specific 3D pelvic model, guiding the design of a customized 3D-printed acetabular implant. Stage two involved implantation of the custom component with fluoroscopic guidance.

Results: Postoperatively, weight-bearing was delayed, followed by structured rehabilitation. The patient showed a decrease in visual analog scale pain score from 8 to 3 and an improvement in Harris Hip Score from 30.45% to 60.65%. She remained complication-free but was lost to follow-up after 6 months.

Conclusion: Staged revision THR supported by advanced imaging and personalized 3D-printed implants offers a viable solution for managing complex acetabular defects in young patients. Early outcomes demonstrate improved stability and function, although long-term validation is needed.

Keywords: Total hip replacement, revision, pseudo-acetabulum, bone defect, three-dimensional printing.

Total hip replacement (THR) offers reliable pain relief and functional improvement, yet revision surgery in young patients remains particularly challenging due to higher activity demands, longer life expectancy, and the increased risk of implant wear, loosening and mechanical failure [1]. These challenges are amplified in individuals with a history of childhood hip trauma or deformity, which can alter anatomy and biomechanics, often predisposing to early implant failure. Accurate pre-operative assessment and strategic planning are essential when managing severe bone loss, as conventional implants may be insufficient for complex defects [2]. Advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing now allow creation of patient-specific implants that replicate individual anatomy, improve implant fit and fixation, and enhance the predictability of reconstructive outcomes. This case report presents a difficult revision THR in a 36-year-old female with long-standing deformity from childhood hip trauma and subsequent implant failure, highlighting the value of staged reconstruction and personalized 3D-printed acetabular implants in addressing complex revision scenarios.

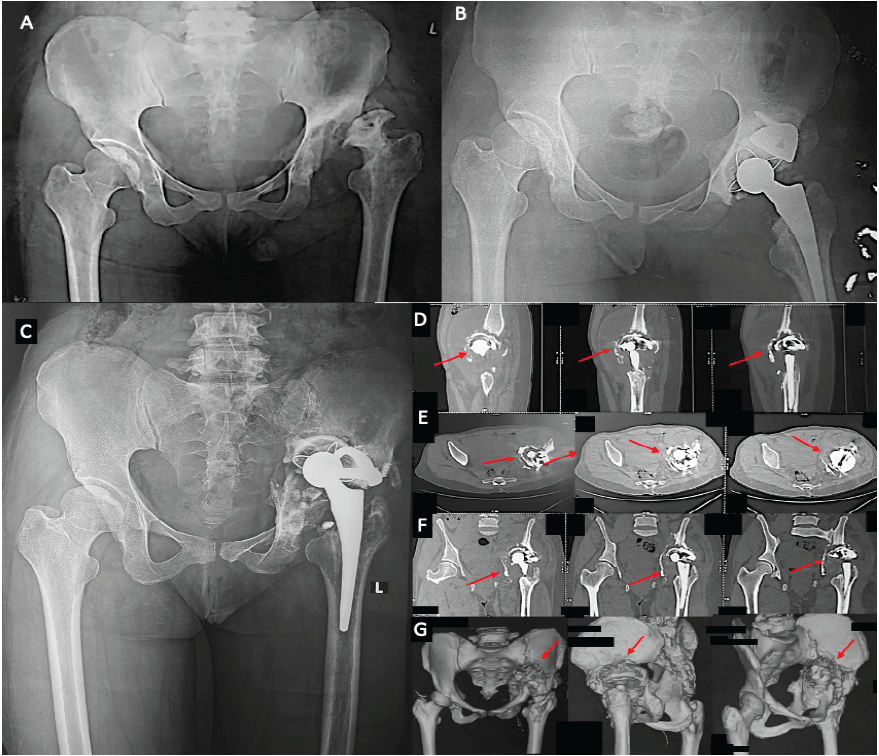

A 36-year-old female, with a history of left THR performed 4 years earlier, presented with progressively worsening left hip pain and difficulty ambulating for 8 months following a fall. The pain was insidious in onset, localized to the left hip, aggravated by prolonged standing and walking, and relieved by rest. She had no significant medical comorbidities. Her initial presentation 4 years prior had included similar hip pain, limb shortening, and restricted range of motion. She also reported a childhood limp secondary to trauma at age 12. Radiographs at that time demonstrated a deformed, fragmented femoral head; a shallow, arthritic acetabulum; and the presence of a pseudo-acetabulum. She subsequently underwent a left THR in which a metal augment was used to address the superolateral acetabular deficiency, and serial reaming was performed to accommodate the shallow acetabular morphology. Her post-operative course was uneventful, with 6 months of supported rehabilitation. At the current visit, examination revealed a bipedal assisted Trendelenburg gait, global restriction of painful hip movements, anterior and posterior joint line tenderness, and a limb length discrepancy. Radiographs showed superior migration and protrusion of the acetabular component, fracture of the anchoring screws of the metal augment, and lateral displacement of the augment. Computed tomography (CT) scan with 3D reconstruction using metal artifact reduction system (MARS) further confirmed implant failure, demonstrating extensive superolateral and acetabular bone loss (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) The pre-operative radiograph before the primary total hip replacement (THR) (first contact) and image, (b) the post-operative primary THR with a metal augment fixation. (c) The radiograph after re-occurrence of symptoms showing implant failure with screw breakage and migration supero-laterally. (d-g) The computed tomography images with three-dimensional reconstruction, showing the bony defects in acetabulum and pelvis.

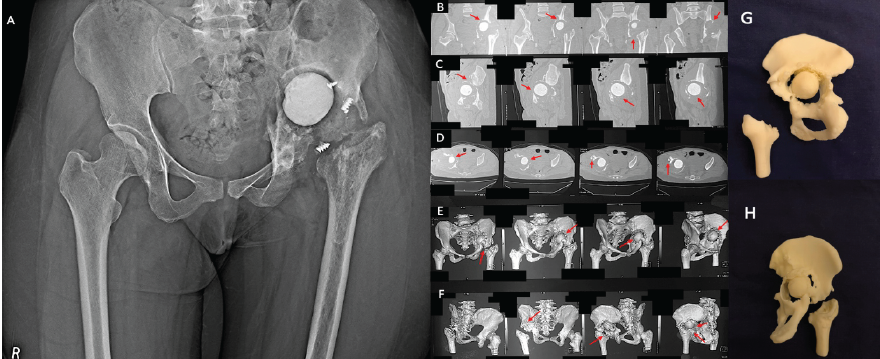

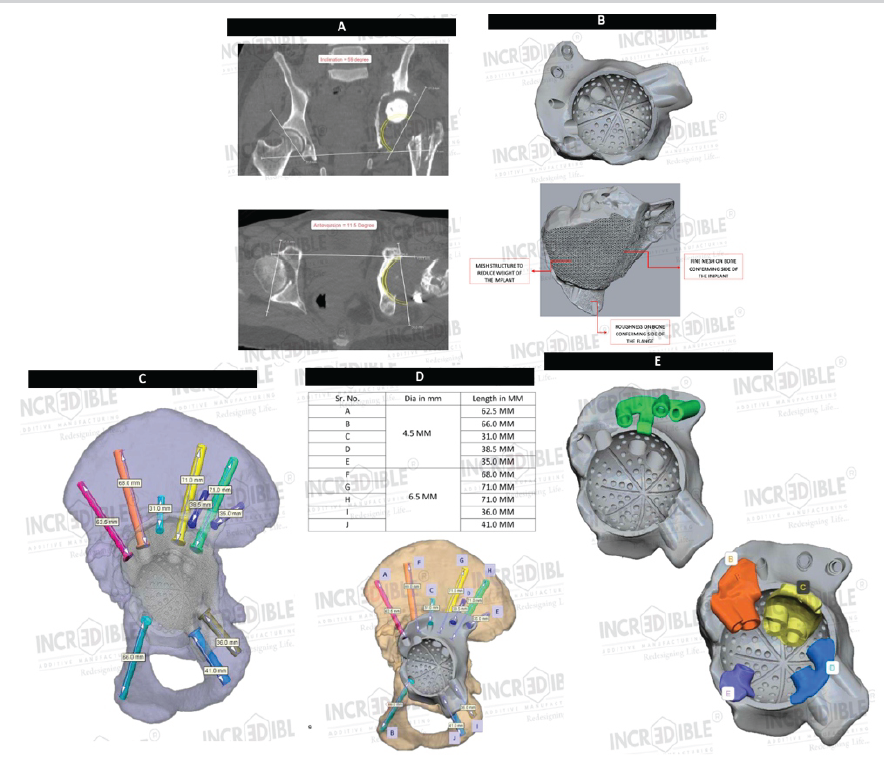

Given the magnitude of acetabular and pelvic defects, conventional revision implants were deemed insufficient. A staged reconstruction using patient-specific, 3D-printed implants was planned. In the first stage, through a Kocher-Langenbeck approach along the previous scar and under spinal anesthesia, dense fibrotic tissue was carefully dissected to facilitate complete implant removal. A cement spacer ball was inserted to temporarily fill the defect. Post-operative recovery was uneventful. A subsequent CT scan revealed persistent superolateral acetabular defects, acetabular floor deficiency, medial loss of the quadrilateral plate, and the cement spacer in situ. The defect was classified as Paprosky Type 3B and American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Type 3. Pre-operative planning for the second stage involved conversion of DICOM CT data into stereolithography (STL) format using 3D-Slicer software. Artifact trimming and STL-based resin printing were used to generate a 3D pelvic model, enabling precise delineation of bony deficiencies (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: (a) The radiograph post removal of implants and placement of cement spacer in situ (Stage 1). (b-f) The computed tomography with metal artifact reduction system sequencing and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction showing the bone loss. (g and h) The 3D printed model from a stereolithography machine for pre-operative planning.

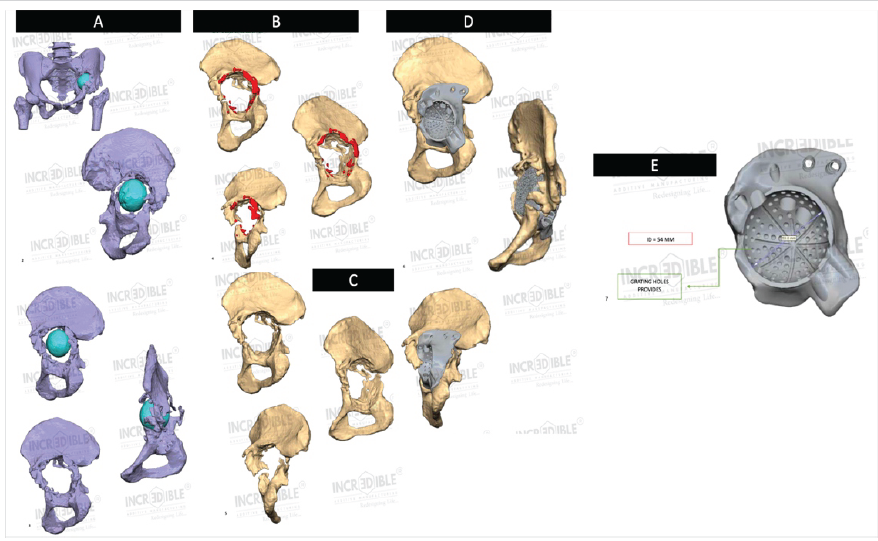

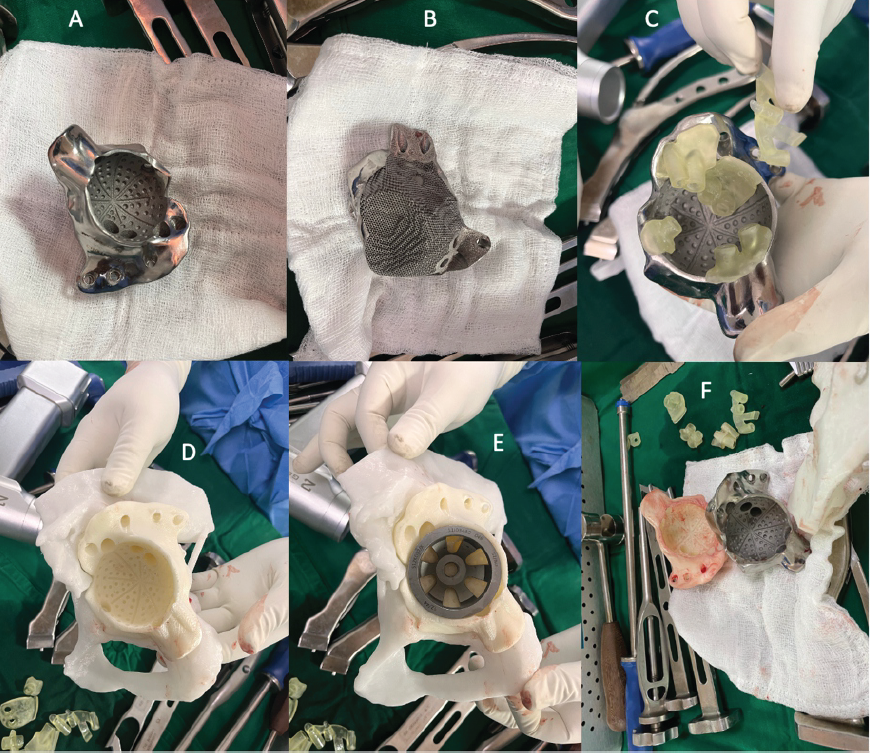

A customized 3D-printed titanium make acetabular implant was designed in collaboration with a specialized manufacturer (Incredible, LimbSal Ortho, Pune, India) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Customized implant design based on three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction DICOM image. (a) The defect anatomy images. (b) The defected left pelvis, where the red highlighted portion is to be removed before implant fixation. (c) The validated image, on which a customized implant is designed, that is, (d). The acetabular cup size measurement is depicted in image (e).

Templating refinements included resection of excess bone, correction of acetabular inclination (59°) and anteversion (11.5°), optimization of mesh architecture to reduce implant weight (Fig. 4) and enhance osseointegration with customization of screw lengths and drill guides based on the 3D model to ensure accurate intraoperative execution (Fig. 5).

Figure 4: (a) Acetabular cup alignment. (b) The implant. (c and d) Screw trajectories and screw length chart, respectively. (e) The drill guides required for screw fixation.

Figure 5: (a and b) She customized three-dimensional-printed implant with drill guides (c). (d and f) The template designs for understanding the distorted anatomy for placement of implant and sizing of total hip replacement components.

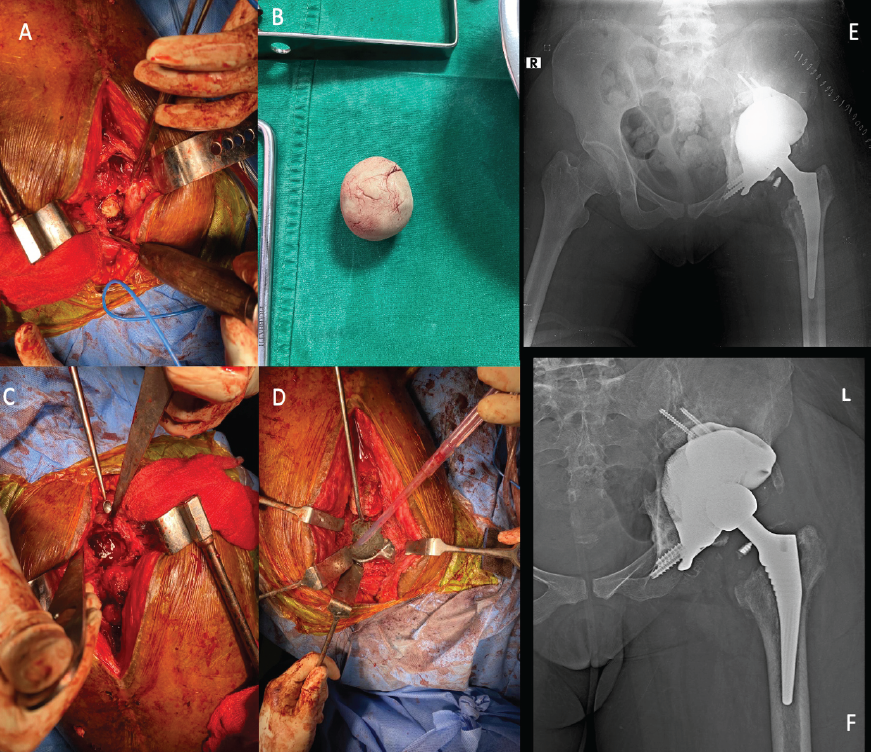

Twelve weeks after stage one, revision reconstruction was performed through the same approach. The cement spacer was removed and bony spurs were excised. The patient-specific 3D-printed acetabular component with augments was implanted and secured using pelvic and acetabular screws under fluoroscopic guidance. An acetabular liner, modular femoral head and neck, and an uncemented femoral stem (Latitud, Meril Life, India) were inserted. Intraoperative assessment demonstrated stable fixation and a satisfactory range of motion. Layered closure was completed in the standard fashion.

Postoperatively, the patient demonstrated a residual limb shortening of approximately 1 cm, which was successfully managed with a heel raise (Fig. 6). There were no early complications. Weight-bearing was intentionally delayed and ambulation initially commenced with non-weight-bearing walking alongside mobility-focused exercises. This was followed by a structured strengthening program over 10 weeks, progression to partial weight-bearing for the subsequent 6 weeks, and eventual transition to full weight-bearing. During this period, the patient’s visual analog scale pain score improved from 8 to 3 and the Harris Hip Score increased from 30.45% to 60.65%. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up after 6 months.

Figure 6: (a and b) The removal of cement spacer. (c) The defect in the acetabulum. (d) The placement of the customized three-dimensional (3D)-printed implant in situ. (e) The immediate post-operative radiograph after fixation of the customized 3D-printed implant with revision total hip replacement. (f) The follow-up radiograph after 6 months.

THR in young patients, typically defined as those under 40–50 years of age, is being undertaken with increasing frequency due to early-onset hip conditions such as osteonecrosis, congenital or developmental deformities, and post-traumatic arthritis [1]. While THR reliably improves pain and function, younger individuals face a disproportionately higher risk of implant-related complications and earlier revision surgery due to higher activity demands and longer life expectancy. As a result, complications such as aseptic loosening, dislocation, mechanical implant failure, and polyethylene wear occur more frequently in this group, underscoring the importance of precise patient selection, advanced surgical techniques, and meticulous pre-operative planning [1,2]. In the present case, the patient sustained childhood trauma to the hip, following which she developed a persistent limp, suggestive of a possible Perthes-like sequelae. This evolved into a deformed femoral head and pseudo-acetabulum formation, ultimately necessitating a primary THR supported with a metal augment. The subsequent failure of this construct in a young, high-demand patient highlights both the technical complexity of reconstruction and the increasing clinical significance of managing severe acetabular bone loss and implant failure in this age group. THR performed for childhood hip sequelae often faces failure due to the complex anatomical and biomechanical alterations from early-life pathology. These include abnormal acetabular morphology such as shallow or dysplastic sockets, femoral deformities, limb length discrepancies and pseudo-acetabulum formation, all contributing to challenges in achieving adequate implant coverage and fixation.3 Soft-tissue contractures and altered muscle balance further increase the risk of instability. Bone stock deficiencies and sclerosis from chronic deformity elevate the risk of aseptic loosening and implant migration [3]. In managing pseudo-acetabulum defects, metal augments are frequently used to provide structural support [3,4]. However, despite employing a metal augment in this case to treat the pseudo-acetabulum, failure still occurred, as evidenced by screw breakage and implant migration. Failed THR commonly presents with progressive hip pain, reduced range of motion, gait abnormalities, limb length discrepancy, and functional limitations. Clinical examination typically reveals joint line tenderness, globally restricted and painful hip movements, and gait deviations such as a Trendelenburg pattern [5]. In our case, the 36-year-old female demonstrated all the hallmark features of THR failure. Radiological assessment remains the cornerstone for diagnosing and planning surgical intervention in failed THRs. Standard radiographs help identify gross abnormalities such as component migration, screw breakage, and bone loss [6]. However, metal implants cause significant artifacts on imaging, limiting detailed evaluation. MARS CT uses advanced algorithms, such as deep learning-based or iterative reconstruction techniques, to significantly reduce metal-induced distortion, thereby enhancing visualization of periprosthetic bone and implant interfaces with higher image quality and diagnostic confidence [6,7]. For meticulous planning, especially in staged revision THR, repeat CT scans employing MARS are essential to accurately ascertain ongoing bone loss and implant status over time, enabling refined surgical strategies and better revision outcomes, as done in our case. In staged revision THR, meticulous pre-operative planning is essential, particularly following the initial stage of implant removal and preliminary assessment of bone loss. Repeat advanced imaging, most commonly CT scans employing MARS technology aid as a tool for effective reconstruction strategy, especially in cases demonstrating severe bone loss patterns. Defects such as Paprosky Type 3B and AAOS Type 3 are characterized by extensive destruction of the acetabular rim and supporting columns, superomedial migration of the hip center, compromised structural integrity, and loss of the quadrilateral plate [8,9]. Under such circumstances, the use of standard revision implants is inadequate and often biomechanically unsatisfactory [8,9]. 3D printing has emerged as a transformative tool in managing these complex defects. By converting CT-derived DICOM data into STL format, patient-specific, anatomically accurate 3D printed pelvic models can be created [10]. These life-size models provide unparalleled spatial, visual, and tactile understanding of the patients’ unique osseous anatomy, allowing the surgical team to assess the defect morphology far more effectively than with imaging alone. In addition, they facilitate precise pre-operative templating of custom acetabular components, enable optimization of implant mesh architecture to reduce weight while maintaining structural strength, and support the design of individualized screw trajectories and drill guides that enhance intraoperative accuracy and reproducibility. This patient-specific, model-guided planning approach has been shown to reduce operative time, intraoperative blood loss, and complication rates by improving implant fit, achieving superior primary stability and aiding in the accurate restoration of the hip’s anatomical center of rotation [10]. In the present case, following first-stage implant removal and cement spacer placement, repeat CT with 3D reconstruction played a pivotal role in guiding the design of a customized 3D-printed acetabular component tailored precisely to the patient’s extensive superolateral and medial pelvic defects. The second-stage reconstruction, supported by 3D printing-assisted planning and intraoperative fluoroscopic guidance, reflects current best practices in the management of advanced acetabular deficiency such as Paprosky Type 3B and AAOS Type 3 defects. Post-operative rehabilitation following staged revision THR typically involves a carefully phased protocol to optimize functional recovery while protecting the reconstruction. Initially, weight-bearing is delayed, generally for 6–10 weeks depending on defect severity and implant stability to allow implant osseointegration and graft healing [11]. Non-weight-bearing ambulation combined with exercises focusing on restoring hip joint mobility is emphasized early on. This phase includes gentle range-of-motion exercises and prevention of stiffness. Subsequent phases incorporate gradual strengthening of periarticular muscles and progressive weight-bearing, typically transitioning through partial weight-bearing for several weeks before full weight-bearing is allowed. Structured physiotherapy also targets gait normalization, proprioception, and correction of compensatory patterns like Trendelenburg gait to improve functional capacity while minimizing complication risks such as dislocation or limb length discrepancy [8,9,11]. In our case, the patient underwent delayed weight-bearing with non-weight-bearing ambulatory exercises focused on mobility and strengthening for approximately 10 weeks, followed by partial weight-bearing for 6 weeks before progressing to full-weight-bearing. The rehab program resulted in substantial improvements in pain relief and hip function. Despite this progress, loss to follow-up after 6 months limits assessment of longer-term outcomes. This rehabilitation trajectory and early functional gains align well with established staged revision THR protocols, reinforcing the need for ongoing clinical and radiological monitoring postoperatively to ensure optimal implant performance and patient function. This study has several important limitations. As a single case report, its findings lack generalizability and are inherently susceptible to selection bias, limiting their applicability to the broader population undergoing revision THR. The short duration of follow-up, restricted to 6 months before the patient was lost to follow-up prevents meaningful evaluation of long-term implant performance, osseointegration, functional outcomes, and late complications such as aseptic loosening, implant wear, or mechanical failure. Moreover, adherence to rehabilitation protocols beyond documented visits cannot be verified, which may influence the accuracy of functional outcome assessment. The complex nature of the case, involving distinctive anatomical deformities and the use of a highly individualized 3D-printed acetabular implant, further restricts the extrapolation of results to routine revision scenarios. Future studies with larger sample sizes, standardized methodologies, and extended follow-up periods are required to substantiate these preliminary observations and clarify the broader role of customized 3D-printed implants in complex acetabular reconstruction.

Revision THR in young patients with complex acetabular defects remains a formidable surgical challenge, particularly when compounded by childhood hip deformities and failure of prior reconstructive procedures. This case demonstrates the critical value of a staged approach combined with advanced imaging and patient-specific 3D-printed implant technology in managing severe Paprosky Type 3B and AAOS Type 3 acetabular deficiencies. The integration of MARS CT-based assessment, 3D pelvic modeling, and customized implant design enabled precise surgical planning, improved intraoperative accuracy, and restoration of biomechanical parameters that would not have been achievable with conventional implants. Early post-operative outcomes revealed meaningful improvements in pain and function, reinforcing the feasibility and potential benefits of personalized 3D-printed acetabular reconstruction in revision THR. Although long-term results could not be assessed due to loss to follow-up, this case highlights the growing role of customized additive-manufactured implants as a viable solution for severe bone loss and complex hip pathology, particularly in younger, high-demand patients. Further clinical studies with larger cohorts and extended follow-up are essential to validate the durability, cost-effectiveness, and broader applicability of this evolving technology in revision hip arthroplasty.

Staged revision THR utilizing advanced imaging techniques and patient-specific 3D-printed implants provides a viable and effective solution for managing complex acetabular bone loss and implant failure in young patients with challenging anatomical deformities, enabling improved implant stability, functional outcomes, and surgical precision where conventional implants are insufficient.

References

- 1. Wang JC, Liu KC, Gettleman BS, Chen M, Piple AS, Yang J, et al. Characteristics of very young patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: A contemporary assessment. Arthroplasty Today 2024;25:101268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Bessette BJ, Fassier F, Tanzer M, Brooks CE. Total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 21 years: A minimum, 10-year follow-up. Can J Surg 2003;46:257-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Oommen AT. Total hip arthroplasty for sequelae of childhood hip disorders: Current review of management to achieve hip centre restoration. World J Orthop 2024;15:683-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Jovanovic Z, Vukomanovic B, Aleksandric D, Jeremic D, Miceta L, Zarkovic ND, et al. The use of porous titanium metal augments for acetabular defects in total hip arthroplasty: Initial results from a single-center experience. Cureus 2025;17:e77307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Aqil A, Shah N. Diagnosis of the failed total hip replacement. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:2-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Selles M, Wellenberg RH, Slotman DJ, Nijholt IM, Van Osch JA, Van Dijke KF, et al. Image quality and metal artifact reduction in total hip arthroplasty CT: Deep learning-based algorithm versus virtual monoenergetic imaging and orthopedic metal artifact reduction. Eur Radiol Exp 2024;8:31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Trabzonlu TA, Terrazas M, Mozaffary A, Velichko YS, Yaghmai V. Application of iterative metal artifact reduction algorithm to CT urography for patients with hip prostheses. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;214:137-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Pandey AK, Zuke WA, Surace P, Kamath AF. Management of acetabular bone loss in revision total hip replacement: A narrative literature review. Ann Joint 2024;9:21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Morales De Cano JJ, Guillamet L, Perez Pons A. Acetabular reconstruction in Paprosky type III defects. Acta Ortop Bras 2019;27:59-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Hughes AJ, DeBuitleir C, Soden P, O’Donnchadha B, Tansey A, Abdulkarim A, et al. 3D printing aids acetabular reconstruction in complex revision hip arthroplasty. Adv Orthop 2017;2017:8925050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Konnyu KJ, Pinto D, Cao W, Aaron RK, Panagiotou OA, Bhuma MR, et al. Rehabilitation for total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2023;102:11-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]