This case underscores the need to consider rare causes, such as Giant Cell Tumor of the Tendon Sheath, in patients with trigger finger, especially when conservative treatment fails.

Dr. Wendy Ghanem, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Balamand, Beirut, Lebanon. E-mail: wendyghanem@gmail.com

Introduction: Trigger finger is a common orthopedic condition that predominantly affects middle-aged individuals. Treatment modalities range from conservative measures like corticosteroid injections to surgical intervention depending on the severity, clinical presentation, and underlying etiology.

Case Report: A 79-year-old female presented with triggering of her middle finger. After conservative treatment failed, further investigation revealed that the condition was caused by a giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath. Surgical excision and reconstruction were performed, resulting in satisfactory clinical outcomes with a full range of motion on follow-up.

Conclusion: This case underscores the importance of considering rare causes for trigger finger, such as tumors, and highlights the need for thorough diagnostic evaluations in persistent or atypical cases of hand pathology.

Keywords: Tendon sheath, trigger finger, tumor.

Trigger finger (stenosing tenosynovitis) is a commonly encountered condition in clinical orthopedic practice, typically affecting individuals between the ages of 40 and 60, with a higher incidence among women (female-to-male ratio of 6:1) [1]. First described in 1850, it is characterized by the inability to flex or extend a digit smoothly due to entrapment of the flexor tendon at the A1 pulley [2]. With an incidence of approximately 2–3% in the general population, trigger finger becomes even more prevalent among specific groups, such as those with diabetes mellitus or rheumatoid arthritis, where the incidence may reach as high as 10% [3,4]. The pathology of trigger finger involves a size mismatch between the retinacular sheath and the underlying flexor tendon. The normal gliding mechanism of the tendon is impaired when inflammation or repetitive microtrauma leads to thickening of the tendon sheath, which then becomes entrapped within the A1 pulley [5]. The diagnosis of stenosing tenosynovitis is clinical when patients often present with pain, tenderness at the base of the affected digit, and a characteristic snapping sensation when attempting to flex or extend the finger. In more advanced cases, the finger may become locked in flexion or extension, limiting hand function and daily activities [3]. While conservative treatment options like corticosteroid injections or splinting may relieve symptoms in most patients, up to 15–20% of cases are refractory to these interventions and require surgical release of the A1 pulley. The differential diagnosis of trigger finger should always include a wide range of potential underlying causes, particularly in cases where conservative treatment fails. These include systemic diseases such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis, as well as structural anomalies and tumors like giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (GCTTS) [6,7]. GCTTS is the second most common benign tumor of the hand, following ganglion cysts, and it is known for its slow, insidious growth. Although it is benign, GCTTS can cause significant functional impairment if it compresses surrounding structures, including the flexor tendons [8]. In rare cases, such as the one described in this report, GCTTS can present as trigger finger, which requires a more tailored treatment approach.

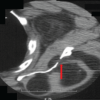

A 79-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented to our orthopedic clinic with a complaint of triggering and locking of her left middle finger. Her symptoms began 3 months prior with intermittent locking of the digit in flexion, which was initially painless. After being treated conservatively at another medical center, including a steroid injection around the A1 pulley, the patient experienced temporary relief. However, her symptoms recurred 2 weeks later, accompanied by increasing pain, swelling, and redness along the volar aspect of the finger. On physical examination, the patient had visible swelling and erythema over the volar side of the middle finger, extending from the proximal palmar crease to the proximal interphalangeal joint. There was a diffuse, palpable, tender mass along the flexor tendon, and the finger exhibited a non-reducible locking in flexion at the A1 pulley. The patient also had limited passive and active range of motion, with significant tenderness along the tendon sheath. Given the lack of response to conservative treatment and the presence of a palpable mass, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hand was obtained. The MRI demonstrated severe distention of the flexor digitorum tendinous sheath of the middle finger, with a lobulated mass of heterogeneous tissue that was hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging and hypointense on T1-weighted imaging (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Magnetic resonance imaging T2 coronal cut of the left hand showing severe distention of the third flexor digitorum tendinous sheath.

The surrounding soft-tissue edema further suggested an inflammatory or neoplastic process, and although tenosynovitis was initially considered, the possibility of a neoplastic etiology, such as a GCTTS, was raised.

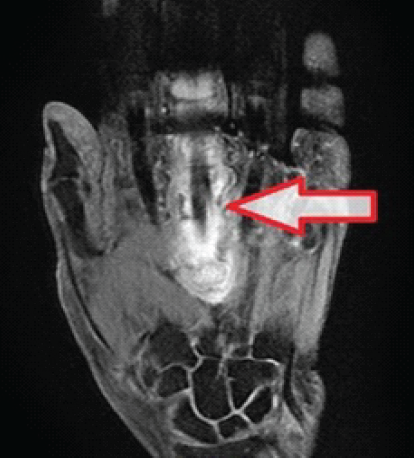

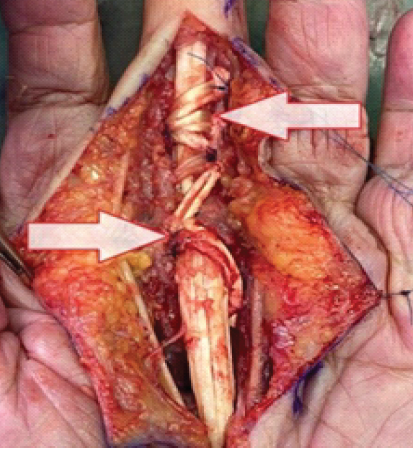

The patient was scheduled for surgical exploration due to the persistence of symptoms and the MRI findings. A Brunner incision was made over the volar aspect of the left middle finger, revealing a well-circumscribed, lobulated tumor extensively involving the flexor tendon sheath. The tumor was adherent to the A1 pulley and had caused attenuation of the surrounding pulleys (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: A lobulated and well circumscribed tumor over the plantar side of the left third finger (red arrows).

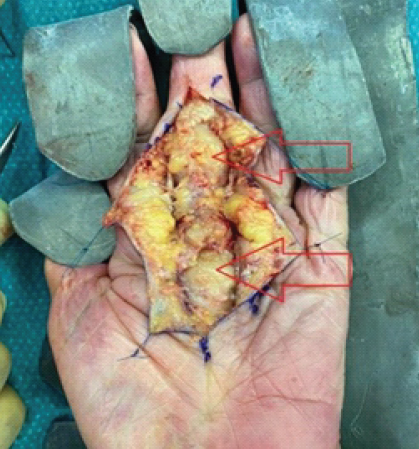

Radical tenosynovectomy was performed, with careful identification and preservation of the neurovascular bundles of the third digit (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Flexor tendon of the left third finger following fasciectomy and synovectomy showing the neurovascular bundles of the third finger (white arrows).

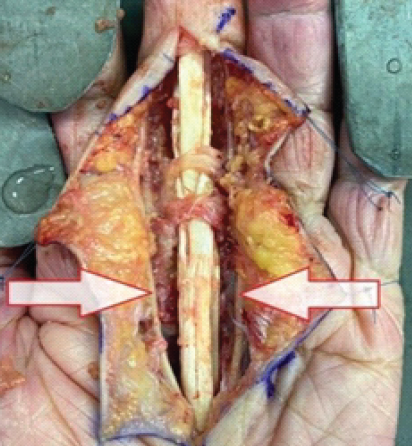

A 12 cm palmaris longus tendon graft was harvested, and reconstruction of the A1, A2, and C2 pulleys was performed using the graft (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Reconstruction of A1, A2 and C2 pulleys using the palmaris longus tendon (white arrows).

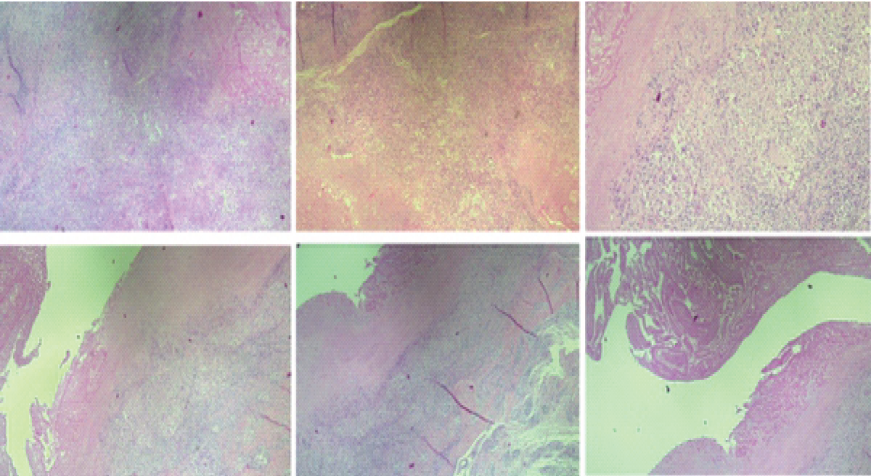

Histopathological examination of the excised tumor confirmed the diagnosis of GCTTS. The specimen showed multiple multinucleated giant cells with hemosiderin deposits, characteristic of GCTTS (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Histopathology slides showing tenosynovial tissue with necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, fibrinoid degeneration, and giant cell reaction.

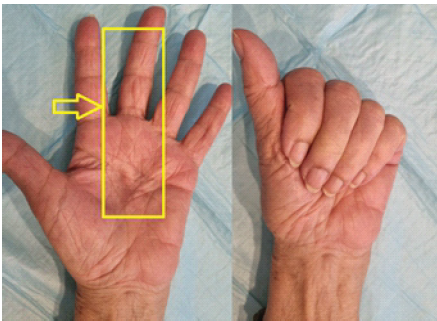

Cultures were negative for bacterial or fungal growth. The patient’s post-operative course was uneventful, and follow-up evaluations at 1, 4, and 12 weeks showed a healed incision with no signs of recurrence, and the patient regained a full range of motion in the affected finger without residual pain or tenderness (Fig. 6). Further follow-up was done at 37 months post-operative, with no evidence of clinical recurrence.

Figure 6: Full range of motion of the third finger 12 weeks post-operative with a completely healed incision (yellow arrow).

Trigger finger is most often attributed to mechanical issues such as thickening of the flexor tendon or its sheath, leading to entrapment at the A1 pulley. However, it is essential to consider less common etiologies when faced with refractory or atypical cases [9]. In particular, neoplastic processes such as GCTTS must be kept in mind when a patient presents with persistent symptoms despite conservative treatment, as in the current case. GCTTS is the second most common benign soft-tissue tumor of the hand, accounting for approximately 1–5% of all hand tumors. It is a slow-growing, benign tumor that arises from the synovial tissue of the tendon sheaths, bursae, and joints. GCTTS predominantly affects individuals between the ages of 30 and 50, with a slight female predominance [10]. The exact pathophysiology of GCTTS is not fully understood; however, some studies suggest that it may be related to chronic inflammation or local trauma, which stimulates the proliferation of synovial cells and leads to the formation of the tumor [11]. GCTTS of the hand usually presents as a painless, firm mass in the hand, often located on the volar aspect of the fingers or wrist [12]. While the tumor typically grows slowly, its location near tendons can lead to mechanical symptoms such as pain, swelling, and in rare cases, trigger finger. There are very few reports in the literature of GCTTS causing trigger finger, with most cases reporting symptoms of painless swelling and limited range of motion. Pozzatti et al. described a case in which a leiomyoma caused trigger thumb in a 61-year-old woman, while another case by Pozzatti and Jones reported pseudo-triggering caused by a giant cell tumor of the extensor tendon sheath of the index finger [13,14]. The diagnosis of GCTTS can be challenging due to its overlap with other benign hand conditions, such as ganglion cysts, fibromas, and lipomas. Imaging studies, particularly MRI, are invaluable in distinguishing GCTTS from other lesions. GCTTS typically appears as a well-defined, lobulated mass with heterogeneous signal intensity on MRI, as seen in the current case. The presence of hemosiderin deposits within the tumor leads to hypointensity on T1-weighted images, while areas of hyperintensity on T2-weighted images correspond to regions of high cellularity or necrosis [15]. Histopathologically, GCTTS is characterized by the presence of multinucleated giant cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and hemosiderin deposits. The treatment of choice for GCTTS is complete surgical excision, though recurrence rates are relatively high, ranging from 10% to 45% depending on factors such as tumor size, invasion of adjacent structures, and incomplete resection [16]. In cases where the tumor involves the flexor tendons or pulleys, as in the current case, reconstruction of the damaged structures may be necessary to restore normal tendon function.

This case highlights the importance of considering rare etiologies, such as GCTTS, in patients presenting with trigger finger, particularly when conservative treatments fail to provide long-term relief. Early imaging, particularly MRI, is critical for identifying neoplastic processes when the clinical presentation is atypical or when conservative treatments are unsuccessful. Surgical excision, with appropriate reconstruction of tendon structures when necessary, is the mainstay of treatment for GCTTS. This case demonstrates the value of a thorough diagnostic approach and timely surgical intervention, which resulted in an excellent outcome for the patient.

Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for rare etiologies, such as giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath, in patients presenting with trigger finger, particularly when symptoms are refractory to conservative treatment.

References

- 1. Schubert C, Hui-Chou HG, See AP, Deune EG. Corticosteroid injection therapy for trigger finger or thumb: A retrospective review of 577 digits. Hand (N Y) 2013;8:439-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Moore JS. Flexor tendon entrapment of the digits (trigger finger and trigger thumb). J Occup Environ Med 2000;42:526-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Green DP, Wolf JM. Trigger finger: Diagnosis and treatment. J Hand Surg Am 2015;40:2018-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Stahl S, Kanter Y, Karnielli E. Outcome of trigger finger treatment in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 1997;11:287-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Saldana MJ. Trigger digits: Diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:246-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Glowacki KA, Weiss AP. Giant cell tumors of tendon sheath. Hand Clin 1995;11:245-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Darwish FM, Haddad WH. Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath: Experience with 52 cases. Singapore Med J 2008;49:879-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Brown CR, Young SM, Hughes JM. Clinical and imaging features of giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath. Clin Imaging 2018;48:58-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Rankin EA, Reid B. An unusual etiology of trigger finger: A case report. J Hand Surg Am 1985;10:904-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Campbell RS, Grainger AJ. Imaging of soft tissue tumors of the hand. Eur J Radiol 2001;43:173-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Al-Qattan MM. Trigger finger due to unusual causes. J Hand Surg Am 2001;26:448-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Canale ST, Beaty JH. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 12th ed. Natherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Pozzatti RR, Cordeiro CP, Da Cruz Jde M, De Araújo GC. Leiomyoma in the thumb causing trigger finger. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015:bcr2015209449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Jones FE, Soule EH, Coventry MB. Fibrous xanthoma of synovium (giant-cell tumor of tendon sheath, pigmented nodular synovitis). A study of one hundred and eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1969;51:76-86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Pulvirenti M, Grasso A, Rizzo L. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath: Analysis of 29 cases. Chir Organi Mov 2015;94:120-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Wilgus BP, Derkash RS. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath: A clinicopathologic review and study of treatment recurrences. J Hand Surg Am 1996;21:636-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]