Benign lipomas adjacent to bone can cause well-demarcated cortical bone erosion due to chronic pressure, a finding that should not be mistaken for malignancy on imaging and should be treated with appropriate surgical management.

Dr. Christopher Warburton, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation, Division of Orthopaedic Oncology, University of Miami Hospital, Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL. E-mail: cswarburton@comcast.net

Introduction: Lipomas are common benign masses of variable size that may be found in a variety of superficial and deep tissues. As a benign growth, lipomas do not typically invade into adjacent structures such as bone. However, when a lipoma has grown large enough, several studies have noted bony erosion in adjacent bony structures. In this series of cases, we report three instances where a large lipoma caused adjacent bony erosion and describe the respective imaging findings.

Case Report: A 57-year-old woman had a left gluteal mass eroding the outer surface of the ilium; a 68-year-old man with a recurrent right buttock lipoma demonstrated similar erosion of the posterior ilium; and a 79-year-old woman had a multilobulated lipoma extending through the scapula from posterior to anterior. In all cases, imaging revealed well-defined, homogenous lipomatous masses with adjacent osseous scalloping best visualized on computed tomography. Histopathology confirmed benign lipomatous tumors with fat necrosis and no evidence of malignancy.

Conclusion: Large, deep lipomas, though benign, can rarely cause pressure-induced erosions of adjacent bony structures. Recognizing this atypical presentation is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis as a malignant tumor and to guide appropriate surgical management.

Keywords: Lipoma, tumor, bone erosion, parosteal lipoma.

Lipomas are the most common benign extremity soft tissue tumors. They can occur in the subcutaneous tissues or in deep somatic tissues either within muscle or more commonly between muscles. Lipomas in general have an unpredictable growth rate. In particular, those that are deep can become very large and efface neurovascular structures and adjacent bone. Unlike malignant tumors, lipomas generally do not invade or erode bone and, despite their prodigious size, cause minimal pain [1,2,3,4]. We describe the clinical and radiographic findings in three patients with large lipomas that caused erosions in bone. It is important to consider lipoma on the differential when a patient presents with the findings and radiographic findings described below, as treatment will differ from a malignant tumor.

Case 1

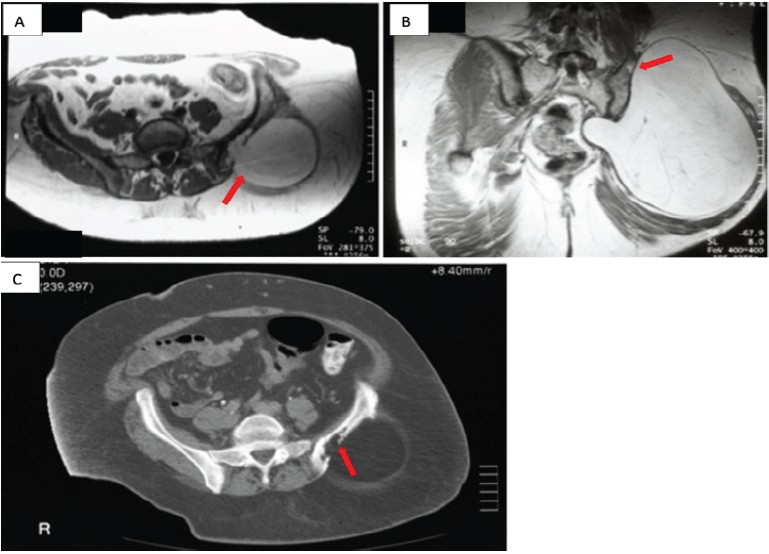

A 57-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of a progressively enlarging mass and pain in her left buttock. The pain was worse with activity but also present at rest. She required analgesic medications for relief of her symptoms. There was no history of antecedent trauma and she denied paresthesias or weakness in the affected lower extremity. She had no bowel or bladder dysfunction and reported no constitutional symptoms or weight loss. On physical examination, there was a large, slightly firm, and non-tender mass occupying nearly the entire left buttock. There were no changes in the skin overlying the mass and examination of the spine revealed no deformity or focal tenderness to deep palpation. She had a full painless, active, and passive range of motion in her lumbosacral spine and hips. She had no neurologic deficit in either lower extremity and her vascular examination was normal. Anterior-posterior (AP) pelvis radiographs showed no apparent osseous abnormality. A technetium-99m pyrophosphate bone scintigram demonstrated no abnormal focal uptake in the involved area. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large lobulated mass in the left buttock abutting the ilium with a homogenous and hyperintense signal on both T1 and T2 axial and coronal images. There was a focal area of hyperintense signal penetrating the outer table of the ilium and replacing the marrow; the inner table was intact (Fig. 1a). Tumor extension into the left sciatic notch was also seen with mild displacement of the pelvic viscera (Fig. 1b). Computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis better demonstrated osseous scalloping of the outer table of the ilium with a well-defined border between the bone and the soft tissue mass (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1: Case 1 imaging findings (a) (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] – axial T1-weighted image) demonstrate erosion of the outer table of the ilium by a large hyperintense and homogenous fatty mass with intramedullary tumor extension (red arrow). (b) (MRI – coronal T2-weighted image) demonstrates focal erosion (red arrow) of the outer table of the ilium superiorly and extension of the tumor into the sciatic notch with medial displacement of the pelvic viscera by the soft tissue mass. (c) (Computed tomography – axial) demonstrates a large osseous erosion in the outer table of the ilium by a large low attenuation mass with some bone remodeling anteriorly (red arrow).

Case 2

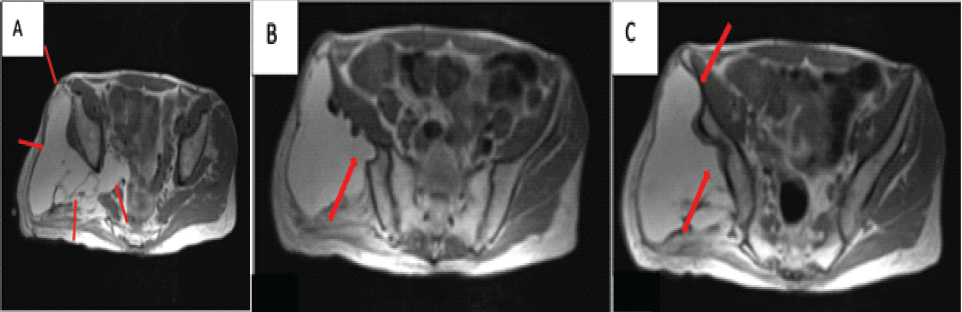

A 68 year-old man presented with a recurrent, non-painful mass in the right buttock. He had two prior resections at outside facilities. The first resection was of an intrapelvic mass performed 27 years before presentation through an anterior approach. The patient reported that this mass was a lipoma but no documentation of the histopathologic evaluation was available for review. The second resection was of a right buttock mass done 1 year before presentation through a posterior approach. Histopathologic interpretation of this mass at the outside hospital was that of a lipoma. Since the second resection, he noted a slow return of the mass along with pain in his right buttock that was associated with prolonged periods of sitting. On physical examination, there was a fullness of the right buttock with an apparent soft tissue mass that was soft and non-mobile. MRI demonstrated a mass that was hyperintense on T1 and T2 pulse sequences consistent with a lipomatous mass. The mass was predominantly in the buttock but extended through the sciatic notch into the retroperitoneal space (Fig. 2a). The majority of the mass appeared to be benign fat with some smaller areas with increased stranding. The mass abutted the posterior aspect of the ilium and appeared to have eroded through the posterior cortex in several places (Fig. 2b and c). There were no changes in the marrow adjacent to the erosions into the ilium. The changes in the ilium were better demonstrated on the CT scan with scalloping of the posterior ilium adjacent to the mass (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 2: Case 2 magnetic resonance imaging T1-weighted imaging findings – axial (a) demonstrates a large fatty mass with some internal septations that extend through the sciatic notch into the retroperitoneal space (red arrow). (b and c) Demonstrates a large fatty mass that abuts the posterior aspect of the ilium which has eroded the posterior cortex in several places (red arrow).

Figure 3: Case 2 computed tomography imaging findings – axial. (a and b) Demonstrates scalloping of the posterior cortex of the ilium by a large low attenuation mass (red arrow).

Intraoperatively, the mass was adherent to the posterior aspect of the ilium. It was separated bluntly from the bone and removed intact utilizing a posterior approach. The mass measured 14 × 14 × 5 cm. Histologically, the mass was consistent with a lipoma with fat necrosis and fibrosis. There were no atypical or overtly malignant features observed microscopically.

Case 3

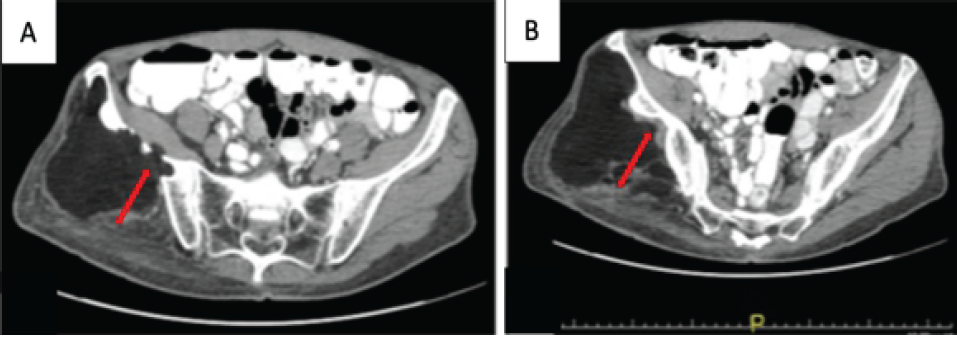

A 79-year-old woman presented with a complaint of a non-painful soft tissue mass in the left axilla of 2-month duration. An incomplete resection of the mass was performed at another institution 6 months before presentation. The histopathologic interpretation of this mass at the outside hospital was that of a low-grade well-differentiated liposarcoma, likely referred to what is now named an atypical lipomatous tumor. On physical examination, there was a large, deep mobile, and non-tender mass adjacent to the chest wall and lateral to the scapula. There was another large, non-tender, bulging mass overlying the posterior surface of the left scapula that did not appear on examination to be contiguous with the axillary mass. The patient was unaware of the posteriorly based mass. An AP radiograph showed focal, well-defined radiolucent defects in the neck and spine of the scapula (Fig. 4). CT and MRI showed a large, multilobulated soft tissue mass around the posterior aspect of the scapula and deep to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. The mass perforated the scapula from posterior to anterior and extended laterally into the axilla; it was contiguous with the axillary mass (Fig. 5a and b). The portion of the mass over the posterior aspect of the scapula was homogenous and hyperintense on T1 and T2 pulse-weighted sequences, whereas the axillary mass was more heterogeneous and somewhat more hypointense on T1 pulse-weighted sequences.

Figure 4: Case 3 radiograph – anteriorposterior (AP) view. AP radiograph demonstrates focal well-defined radiolucent defects in the neck and spine of the scapula (red arrow).

Figure 5: Case 3 computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] T1-weighted – axial. (a) CT demonstrates a large multilobulated low attenuation mass abutting the posterior aspect of the scapula which has eroded through bone to the anterior aspect of the scapula and which extends laterally into the axilla (red arrow). (b) T1-weighted MRI demonstrates a large multilobulated fatty mass eroding into and through the posterior aspect of the scapula that on the inset is seen to be contiguous with the axillary mass (red arrow).

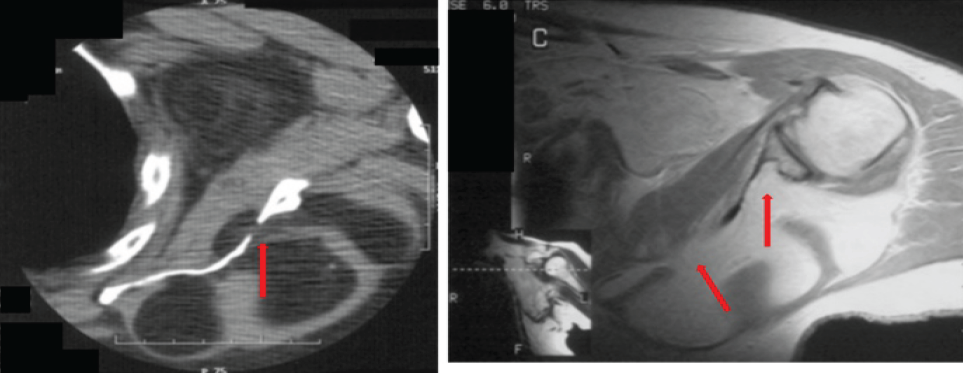

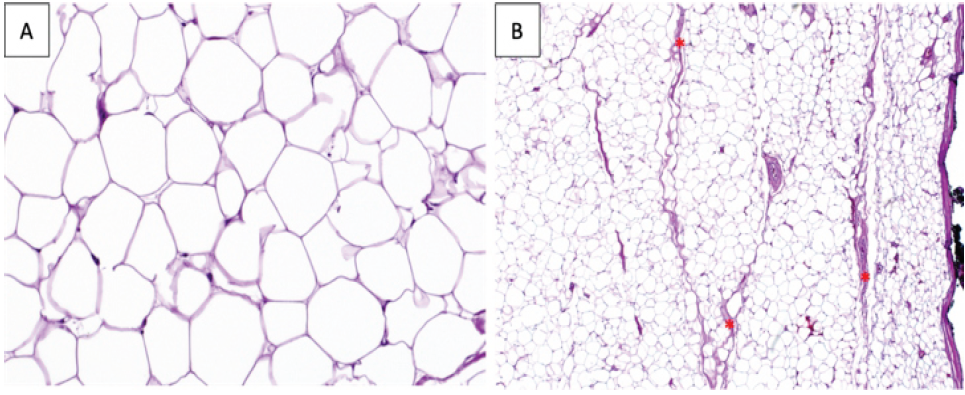

Lipomas, the most common benign soft tissue tumors of the extremities, can often be accurately diagnosed with advanced imaging studies [1,2,3,4]. Lipomas are typically homogeneously hyperintense on both T1 and T2-weighted pulse sequences, suppress on STIR images, and lack prominent septations. Rarely, lipomas erode adjacent bone as demonstrated in the cases described herein. Parosteal, intraosseous, and lipoma arborescens lipomas are among the tumor types that should be considered on the differential. Lipomas that are primarily osseous in origin are described as either intraosseous lipomas or parosteal lipomas [5]. Parosteal lipomas arise on the surface of the bone, originate in the outer fibrous layer of the periosteum, and may exhibit varying degrees of mineralization in the soft tissues [6,7,8]. However, in the cases presented herein, the lipomas arose adjacent to the bone rather than within the bone or periosteum. Histologically, lipomas demonstrate mature lipocytes with interspersed fat necrosis and reactive changes, without findings that could be ascribed to an atypical lipomatous tumor or a malignancy (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Histology example. This histology sample was taken from a lipoma that arose in the proximal humerus of a separate case not detailed in this series. ×100 magnification (a) demonstrates the typical mature lipocytes. ×40 magnification (b) demonstrates a lipomatous tumor with occasional fat necrosis (red*). These findings were consistent and representative of the histological findings in each of the cases described in this series.

Large juxtacortical malignant soft tissue masses can penetrate bone, although the periosteum is usually an effective barrier to tumor growth. Benign soft tissue tumors, except for neurofibromas and fibromatosis, rarely erode long bones. The large flat bones however are relatively devoid of periosteum and the cortices are thin, thus rendering these bones vulnerable to pressure erosion by expanding soft tissue masses. Presumably, pressure produced by these large soft tissue masses at the bone soft tissue interface induces focal osteoclastic resorption of bone, resulting in the defects observed radiographically (specifically, well-defined lucencies). Grossly, these changes in the bone appear as large scallops. To our knowledge, there have been very few reported cases of lipomas causing osseous erosions, and no reports of these erosions occurring in the pelvis. Lloyd reported a case of a lipoma causing osseous erosions in the scapula [9]. Leffert reported a case of erosion of an adjacent metacarpal by a lipoma arising in the palm and Kitagawa reported a case of erosion of a distal phalanx by a lipoma in a finger [10,11]. Other reports of cases of erosion of bone include those by Shawker (a rib erosion from an intrathoracic lipoma in an infant), Braunschweig (erosion of the bones of the foot by a spindle cell lipoma) and by Preul (angiolipomas of the spine) [12,13,14]. Chae reported a case of lipoma arborescens of the glenohumeral joint eroding into the humeral head and Ryu described marginal erosions in subchondral bone in patients with lipoma arborescens of the knee [15,16]. In the three cases reported here, the erosion of the ilium and the scapula is postulated to have occurred due to direct pressure on the bone by the large expanding lipomas growing deep to the gluteal muscles in the first two cases and deep to the posterior scapular muscles in the third case. The underlying cortex of the ilium and scapula is quite thin and thus more vulnerable to pressure erosion by an expanding adjacent soft tissue mass.

In summary, large lipomatous tumors arising around the flat bones may cause erosions in bone that can be seen on MRI as lobular extensions of fat into the outer cortex. The erosions are best observed on CT imaging. These tumors may also have areas of mineralization and fat necrosis, resulting in heterogeneity that may be interpreted as atypical or overtly malignant. It is important to recognize that both of these findings may be seen in patients with benign tumors of fat, where the appropriate treatment is marginal tumor excision alone.

When a patient presents with a soft-tissue mass that erodes adjacent bone, a benign lipoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Although many referring attendings will assume that the findings are associated with a malignant process, further histopathological analysis can differentiate the mass as a benign lipoma eroding adjacent bone, which is a much more benign condition than a malignant tumor.

References

- 1. Bancroft LW, Pettis C, Wasyliw C. Imaging of benign soft tissue tumors. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2013;17:156-67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Cavanagh RC. Tumors of the soft tissues of the extremities. Semin Roentgenol 1973;8:73-89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kransdorf MJ, Jelinek JS, Moser RP Jr. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. Radiol Clin North Am 1993;31:359-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Papp DF, Khanna AJ, McCarthy EF, Carrino JA, Farber AJ, Frassica FJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft-tissue tumors: Determinate and indeterminate lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89 Suppl 3:103-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Mangham DC, Beggs I, Teh J, Davies AM. Intraosseous lipoma: Report of 35 new cases and a review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol 2003;32:209-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Jacobs P. Parosteal lipoma with hyperostosis. Clin Radiol 1972;23:196-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Miller MD, Ragsdale BD, Sweet DE. Parosteal lipomas: A new perspective. Pathology 1992;24:132-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Blair TR, Resnick D. Subperiosteal lipoma: A case report. Clin Imaging 2000;24:381-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Lloyd TV, Paul DJ. Erosion of the scapula by a benign lipoma: Computed tomography diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1979;3:679-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Leffert RD. Lipomas of the upper extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972;54:1262-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Kitagawa Y, Tamai K, Kim Y, Hayashi M, Makino A, Takai S. Lipoma of the finger with bone erosion. J Nippon Med Sch 2012;79:307-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Shawker TH, Dennis JM, Nilprabhassorn P. Benign intrathoracic lipoma with rib erosion in an infant. Radiology 1972;104:111-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Braunschweig IJ, Stein IH, Dodwad MI, Rangwala AF, Lopano A. Case report 751: Spindle cell lipoma causing marked bone erosion. Skeletal Radiol 1992;21:414-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Preul MC, Leblanc R, Tampieri D, Robitaille Y, Pokrupa R. Spinal angiolipomas. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg 1993;78:280-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Chae EY, Chung HW, Shin MJ, Lee SH. Lipoma arborescens of the glenohumeral joint causing bone erosion: MRI features with gadolinium enhancement. Skeletal Radiol 2009;38:815-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Ryu KN, Jaovisidha S, Schweitzer M, Motta AO, Resnick D. MR imaging of lipoma arborescens of the knee joint. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;167:1229-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]