Chondroblastoma with secondary aneurysmal bone cyst is diagnostically challenging, often mimicking primary aneurysmal bone cyst or giant cell tumor on imaging, and is effectively treated with intralesional curettage, achieving good outcomes despite 10–15% recurrence rates requiring long-term surveillance.

Dr. Silambarasi Nagasamy, Department of Orthopaedics, Parvathy Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: silambarasi.sn@gmail.com

Introduction: Chondroblastomas (CB) are rare benign cartilaginous tumors (1%) arising from secondary ossification centers in epiphysis of long bones, commonly the proximal humerus. They commonly occur in the 2nd decade of life and have a male predilection. The occurrence of these tumors in the patella is extremely rare (<2%).

Case Report: A 16-year-old male presented with knee pain since 2 months, which aggravated with activities. Radiographic evaluation showed an osteolytic lesion along the superolateral pole of patella, which was hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 along with multiple fluid-fluid levels, suggestive of aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC). Intralesional curettage was performed along with bone grafting from the ipsilateral iliac crest. Histopathological examination showed presence of chondroblasts along with abundant osteoclast-like giant cells, suggestive of a CB with a secondary ABC. The patient was able to return to his day-to-day activities after 4 weeks.

Conclusion: CB with secondary ABC represents a diagnostic challenge due to atypical imaging features that mimic primary ABC. One must maintain high suspicion for this entity when evaluating lytic patellar lesions. Adequate tissue sampling and histopathological examination are mandatory for accurate diagnosis, as radiological findings alone are insufficient. Appropriate surgical management with intralesional curettage and bone grafting results in excellent functional recovery and low recurrence rates.

Keywords: Chondroblastoma, patella, secondary aneurysmal bone cyst, aneurysmal bone cyst.

Chondroblastomas (CBs) account for approximately 1–2% of all primary bone tumors and typically arise from secondary ossification centers of the epiphysis and growth plate [1,2]. While these benign tumors most commonly affect the proximal epiphysis of the femur, humerus, and tibia, patellar involvement occurs in <2% of cases [3]. Although predominantly seen in children and adolescents, they rarely present in adults. The diagnostic challenge intensifies when CB occurs with secondary aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs), a rare combination that clinically and radiologically mimics both giant cell tumors (GCTs) and primary ABCs [4,5]. Jaffe and Lichtenstein identified key distinguishing features of CB, including focal areas of calcification and necrosis, which help differentiate it from GCTs [6]. However, distinguishing CB with secondary ABC from primary ABC requires histopathological confirmation due to their overlapping imaging characteristics [7]. Despite its rarity, CB with secondary ABC has been documented in various locations including the patella, metacarpal bone, and skull, with management via various approaches ranging from curettage and bone grafting to radiofrequency ablation [8,9,10]. We present a case of patellar CB with secondary ABC that was initially misdiagnosed as a primary ABC of the patella, highlighting the diagnostic complexity of this entity.

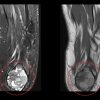

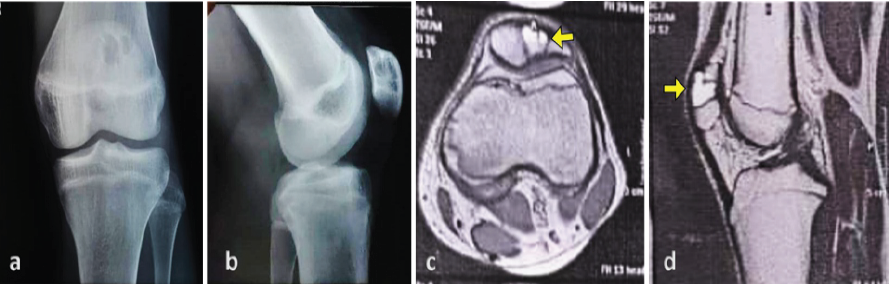

A 16-year-old male cricketer presented with a 2-month history of dull aching, anterior knee pain that had aggravated over the preceding 2 weeks. The pain was exacerbated by physical activities but did not restrict mobility. There was no history of trauma. Clinical examination revealed quadriceps muscle wasting with no obvious swelling or tenderness. The range of motion was preserved, while floating patella test and special tests for ligamentous injuries were negative. Plain radiographs of the left knee showed a well-defined lytic lesion along the superolateral aspect of the patella, with a narrow zone of transition and no perilesional sclerosis (Fig. 1). The joint space remained unaffected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 2.5 × 1.4 × 2.1 cm mild expansile patchy lesion with clear margins, and narrow zone of transition, hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2. Multiple fluid-fluid levels were observed on sagittal T2 sequences, leading to a pre-operative diagnosis of ABC of the patella (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Imaging studies of the knee. (a and b) Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs demonstrate a well-defined osteolytic lesion within the patella. (c and d) Axial and sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging sections reveal fluid-fluid levels within the lesion.

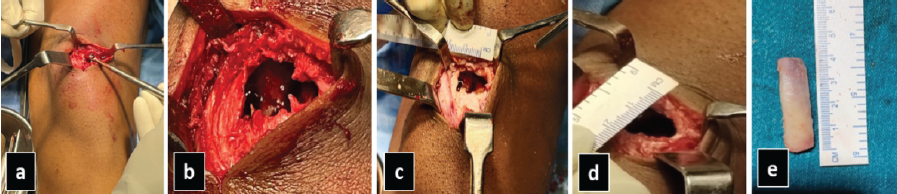

The patient underwent intralesional curettage with en bloc tumor resection. The resultant defect was filled using a tricortical iliac crest bone graft harvested from the ipsilateral ilium, and was shaped to fit the excised cavity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Intraoperative photographs demonstrating (a) intralesional curettage, (b) cavity following tumor removal, (c) transverse and (d) longitudinal measurements of the defect, and (e) dimensions of the harvested iliac crest bone graft.

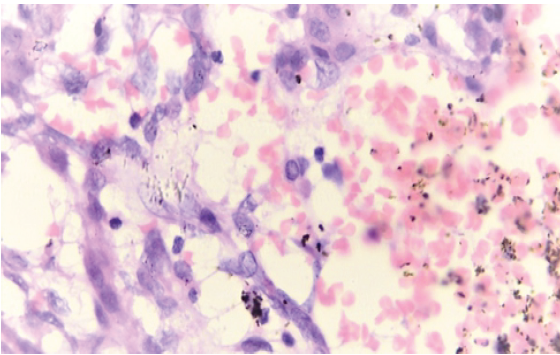

Histopathologic examination revealed round to polyhedral chondroblasts with abundant eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm within a pink chondroid matrix, hyperlobulated and grooved nuclei, abundant osteoclast-like giant cells, capillaries, and hemosiderin deposits which were consistent with the features of CB [11] (Fig. 3). The final diagnosis was CB of the patella with secondary ABC.

Figure 3: Histopathological examination revealed round to polyhedral chondroblasts with hyper-lobulated, grooved nuclei within a pink chondroid matrix, along with osteoclast-like giant cells.

Postoperatively, the patient was immobilized in an extension knee brace for 4 weeks, after which functional rehabilitation exercises were initiated. At 6-month follow-up, there was no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence (Fig. 4), and the patient had returned to his sporting activities without pain.

Figure 4: Six-month post-operative radiograph demonstrating graft incorporation within the patellar defect.

The combination of CB with secondary ABC presents a diagnostic challenge, as the clinical and radiological features closely mimic those of GCT or primary ABC, making accurate pre-operative diagnosis difficult [4,7]. The findings from our case are consistent with those of multiple other studies documenting CB with secondary ABC-like changes. Zheng et al. reported a case of a 30-year-old male with patella CB and secondary ABC that was initially misdiagnosed as GCT with secondary ABC based on the patient’s age and imaging findings [7]. Their diagnostic experience mirrors ours, as both cases presented with osteolytic lesions and fluid-fluid levels on MRI that obscured the typical imaging characteristics of CBs, such as scattered calcifications and sclerotic margins. This is corroborated by Singh et al., who emphasized that the three most common bone tumors affecting the patella are GCT (33%), CB (16%), and ABC (5%), which share common clinical presentations and imaging characteristics, particularly in the presence of a secondary ABC [4]. Similarly, our patient’s presentation with anterior knee pain, osteolytic lesion, and multiple fluid–fluid levels on MRI was indistinguishable from primary ABC, demonstrating how secondary ABC-like changes can mask the features of the underlying CB. Alkadumi et al. reported CB of the knee in a teenager and noted that clinical symptoms, while non-specific, were often revealed following trauma [12]. While their case involved the distal femoral epiphysis rather than the patella, the authors placed emphasis on the fact that definitive diagnosis relies primarily on histopathology due to lack of specificity of radiological findings. This was applicable to our case as well. Typical features of CB, such as scattered calcifications and sclerotic margins, were absent in our patient, and were likely obscured by the dominant ABC component, reinforcing the aforementioned observation. Tan et al. reported a case of patellar CB with ABC and similarly, highlighted the importance of recognizing that when CB is combined with secondary ABC, its imaging features become atypical or even masked [13]. Foo et al. presented a unique approach of treating CB of the skull base with ABC-like changes using combined percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for the CB component and doxycycline sclerotherapy for the ABC component [9]. Although this case report involved a different anatomical location, it establishes the principle of addressing each component separately when two entities are present. In contrast, our case was successfully managed with intralesional curettage and en bloc tumor resection followed by tricortical iliac crest bone grafting, which is consistent with the traditional approach to such lesions. Xu et al. reviewed 130 cases of extremity CB and found that extended intralesional curettage with local adjuvants resulted in a recurrence rate of approximately 10–15%, supporting curettage and grafting [14]. Rybak et al. reported successful treatment of appendicular CBs using radiofrequency ablation with only 6% recurrence and full return to activities at mean follow-up of 41.3 months [15]. However, the site and the presence of a secondary ABC in our case made the traditional surgical approach a more suitable one. In terms of diagnostic accuracy, Zheng et al. emphasized that fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy achieve only 70% and 81% accuracy respectively for bone lesions with secondary ABC, advocating for incision biopsy as the gold standard [7]. While Cleven et al. highlighted the utility of H3F3B mutation analysis (K36M) in distinguishing CB from GCT with H3F3A mutations (G34W) [16], conventional histopathology proved useful in our case as it showed the characteristic chondroblasts with grooved nuclei and chondroid matrix. Our use of intralesional curettage with tricortical iliac crest autografting is similar to treatment protocols described by Zekry et al. and Lang et al., both reporting successful outcomes with curettage and bone grafting for CB [17,18]. Our patient’s complete return to sporting activities at 6-month follow-up supports our line of management, though Laitinen et al. emphasize the importance of long-term surveillance given the 10–15% recurrence rate of these lesions [19]. Konishi et al. demonstrated that CB with ABC-like changes responds similar to isolated CBs when adequately excised [20], although Behjati et al. noted that rare malignant transformation or pulmonary metastases can occur following inadequate treatment, warranting the need for continued follow-up [21].

Patellar CB with secondary ABC remains a rare and diagnostically challenging entity that can easily be mistaken for primary ABC or GCT. The presence of secondary ABC-like changes effectively masks the characteristic imaging features of CB, making pre-operative radiological diagnosis unreliable. High clinical suspicion coupled with adequate histopathological sampling is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate surgical management. Intralesional curettage with bone grafting provides excellent functional outcomes when the diagnosis is accurately established, emphasizing the critical importance of definitive tissue diagnosis in guiding treatment decisions for atypical patellar bone lesions.

When evaluating lytic patellar lesions, particularly those demonstrating fluid–fluid levels on MRI, clinicians should maintain high suspicion for CB with secondary ABC despite imaging features suggesting primary ABC. Radiological findings alone are insufficient for accurate diagnosis, and adequate tissue sampling with histopathological confirmation is mandatory before definitive treatment. Early recognition and appropriate surgical management ensure optimal functional recovery and return to activities.

References

- 1. Chen W, DiFrancesco LM. Chondroblastoma: An update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:867-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kurt AM, Unni KK, Sim FH, McLeod RA. Chondroblastoma of bone. Hum Pathol 1989;20:965-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Song M, Zhang Z, Wu Y, Ma K, Lu M. Primary tumors of the patella. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Singh J, James SL, Kroon HM, Woertler K, Anderson SE, Jundt G, et al. Tumour and tumour-like lesions of the patella–a multicentre experience. Eur Radiol 2009;19:701-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Gutierrez LB, Link TM, Horvai AE, Joseph GB, O’Donnell RJ, Motamedi D. Secondary aneurysmal bone cysts and associated primary lesions: Imaging features of 49 cases. Clin Imaging 2020;62:23-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L. Benign chondroblastoma of bone: A reinterpretation of the so-called calcifying or chondromatous giant cell tumor. Am J Pathol 1942;18:969-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Zheng J, Niu N, Shi J, Zhang X, Zhu X, Wang J, et al. Chondroblastoma of the patella with secondary aneurysmal bone cyst, an easily misdiagnosed bone tumor: A case report with literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Huang C, Lü XM, Fu G, Yang Z. Chondroblastoma in the children treated with intralesional curettage and bone grafting: Outcomes and risk factors for local recurrence. Orthop Surg 2021;13:2102-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Foo MI, Nicol K, Murakami JW. Skull base chondroblastoma with aneurysmal bone cyst-like changes treated with percutaneous radiofrequency ablation and doxycycline sclerotherapy: Illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons 2022;4:CASE22436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Restrepo R, Zahrah D, Pelaez L, Temple HT, Murakami JW. Update on aneurysmal bone cyst: Pathophysiology, histology, imaging and treatment. Pediatr Radiol 2022;52:1601-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Schajowicz F, Gallardo H. Epiphysial chondroblastoma of bone. A clinico-pathological study of sixty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970;52:205-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Alkadumi M, Duggal N, Kaur S, Dobtsis J. Chondroblastoma of the knee in a teenager. Radiol Case Rep 2021;16:3729-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Tan H, Yan M, Yue B, Zeng Y, Wang Y. Chondroblastoma of the patella with aneurysmal bone cyst. Orthopedics 2014;37:e87-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Xu H, Nugent D, Monforte HL, Binitie OT, Ding Y, Letson GD, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone in the extremities: A multicenter retrospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:925-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Rybak LD, Rosenthal DI, Wittig JC. Chondroblastoma: Radiofrequency ablation–alternative to surgical resection in selected cases. Radiology 2009;251:599-604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Cleven AH, Höcker S, Briaire-de Bruijn I, Szuhai K, Cleton-Jansen AM, Bovée JV. Mutation analysis of H3F3A and H3F3B as a diagnostic tool for giant cell tumor of bone and chondroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:1576-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Zekry KM, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Araki Y, Alkhooly AZ, et al. Surgical treatment of chondroblastoma using extended intralesional curettage with phenol as a local adjuvant. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27:2309499019861031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Lang Y, Yu Q, Liu Y, Yang LJ. Chondroblastoma of the patella with pathological fracture in an adolescent: A case report. World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Laitinen MK, Stevenson JD, Evans S, Abudu A, Sumathi V, Jeys LM, et al. Chondroblastoma in pelvis and extremities-a signle centre study of 177 cases. J Bone Oncol 2019;17:100248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Konishi E, Nakashima Y, Mano M, Tomita Y, Kubo T, Araki N, et al. Chondroblastoma of extra-craniofacial bones: Clinicopathological analyses of 103 cases. Pathol Int 2017;67:495-502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Behjati S, Tarpey PS, Presneau N, Scheipl S, Pillay N, Van Loo P, et al. Distinct H3F3A and H3F3B driver mutations define chondroblastoma and giant cell tumor of bone. Nat Genet 2013;45:1479-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]