In Kabuki Syndrome intrinsic ligamentous laxity and immune vulnerability can amplify the risk of proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK) after spinal fusion; preventive surgical planning and biological optimization are critical for durable correction.

Dr. João Nóbrega, Department of Orthopaedics, Sao Jose Local Health Unit, Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: joao.nobrega2@ulssjose.min-saude.pt

Introduction: Kabuki syndrome (KS) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by distinctive facial features, intellectual disability, and multiple musculoskeletal anomalies, including scoliosis, kyphosis and generalized ligamentous laxity. The combination of connective tissue fragility and complex spinal deformity may predispose these patients to post-operative complications, such as proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK), though this association has not previously been reported.

Case Report: We report a 15-year-old male with genetically confirmed KS who presented with severe thoracic hyperkyphosis (95°). Posterior spinal fusion and correction were performed, resulting in initial improvement. Within 8 months, the patient developed PJK above the upper instrumented vertebra, requiring multiple revision procedures. Post-operative infection with Staphylococcus aureus and rapid recurrent kyphosis further complicated management. A staged revision strategy, combining halo-gravitational traction followed by extended fusion and careful sagittal realignment, achieved stable correction and functional improvement at 2-year follow-up.

Conclusion: The association between these conditions has, to our knowledge, not yet been reported in literature. This case highlights the multifactorial etiology of PJK in KS, where intrinsic ligamentous laxity, immune dysfunction, and extensive deformity correction converge to increase mechanical vulnerability. Soft-tissue preservation at the upper instrumented level, careful sagittal contouring and infection control are key preventive strategies. Due to inherent ligamentous laxity and connective tissue abnormalities, patients with KS could be predisposed to proximal junctional failure after spinal deformity correction. Pre-operative recognition of connective tissue and immunologic abnormalities, together with detailed surgical planning, is essential to minimize complications and optimize long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Kabuki Syndrome, proximal junctional kyphosis, spinal deformity, thoracic hyperkyphosis, joint hypermobility.

Kabuki Syndrome (KS) is a rare congenital disorder typically caused by pathogenic variants in the KMT2D gene (autosomal dominant) and less frequently in KDM6A (X-linked dominant), with a subset of cases remaining genetically unexplained [1]. This syndrome is characterized by distinctive facial features, postnatal growth deficiency, intellectual disability, and multiple congenital anomalies, including cardiovascular, urogenital and musculoskeletal abnormalities. Musculoskeletal involvement is frequent, encompassing scoliosis, kyphosis, joint hypermobility (50–75%), and vertebral malformations such as hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebrae, and sagittal clefts [2,3]. Spinal deformities, particularly kyphosis and scoliosis, may progress during growth, often requiring surgical correction. However, patients with generalized joint laxity or syndromes characterized by ligamentous laxity and joint hypermobility may be predisposed to more severe adjacent segment degeneration after spine surgery [4]. Proximal Junctional Kyphosis (PJK) is a well-documented post-operative complication characterized by an abnormal increase in kyphosis at the spinal segments immediately above the upper instrumented vertebra (UIV) following posterior spinal fusion. The classic and most widely used definition is a >10° sagittal Cobb angle between the UIV and the 2 vertebrae proximal to the superior endplate, and at least 10° greater than the pre-operative measurement [5]. Studies have identified ligamentous failure as a primary mechanism underlying PJK after posterior spinal fusion, especially in pediatric and syndromic populations [6,7]. The risk is further elevated in cases with pre-operative hyperkyphosis, extensive segmental correction and longer fusion constructs [6,7]. In the context of KS, ligamentous laxity may correspond to a risk factor, as the weakened connective tissue at the junctional segments is less able to withstand post-operative biomechanical stresses. The association between these conditions has, to our knowledge, not yet been reported in the literature, representing a challenging orthopedic scenario. We present a case of a patient with KS and thoracic hyperkyphosis who developed PJK following surgical correction. This report discusses the surgical management and post-operative complications, underscoring the multifactorial etiology of junctional complications, where both intrinsic (syndromic ligamentous laxity) and extrinsic (surgical correction magnitude, fusion level selection) factors converge.

A 15-year-old male with genetically confirmed KS (KMT2D variant) was referred to our orthopedic department for evaluation of progressive thoracic deformity and worsening back pain. His medical history was notable for congenital heart disease, dysplastic aorta, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and multiple joint dislocations. There was no history of prior spinal surgery.

Clinical and radiological findings

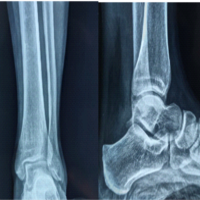

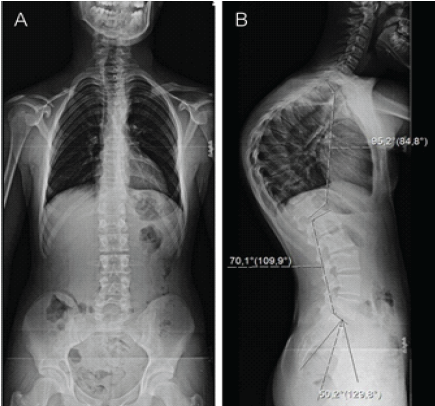

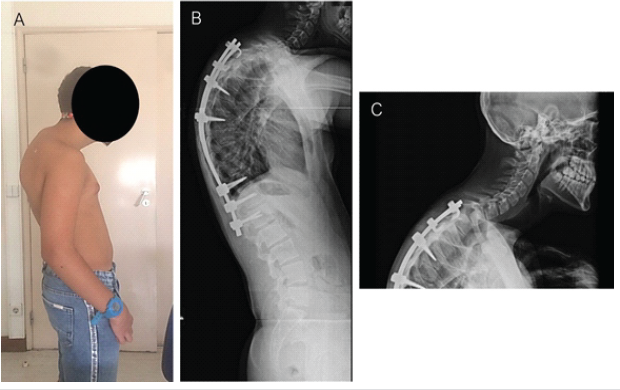

Physical examination revealed a marked and fixed thoracic kyphosis that did not correct with active extension or positional changes. No clinical evidence of scoliosis or neurological deficit was identified. At the time of presentation, the patient’s skeletal maturity corresponded to Risser stage 4. Standing lateral full-length spine radiographs demonstrated thoracic hyperkyphosis with a Cobb angle of 95° (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging findings were within normal limits.

Figure 1: Full-length spine radiographs (a) – anteroposterior view and (b) – lateral view of thoracic hyperkyphosis with a 95° Cobb angle.

Surgical procedure

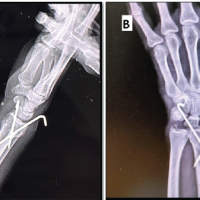

Given the severity and progressive nature of the deformity, posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion were performed. Pedicle screws were inserted at T5, T7, T11, T12, and L1; transverse process hooks were applied at T2 and T3 levels; and Smith-Petersen osteotomies were carried out from T6 to T10. Deformity correction was achieved using the cantilever technique, followed by posterolateral fusion with autologous bone graft. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring remained stable throughout the procedure. Post-operative imaging confirmed satisfactory correction, with a reduction of the thoracic Cobb angle to 60° (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Post-operative full-length spine lateral view radiographs showing a Cobb angle of 60° and neutral sagittal vertical axis.

Post-operative course

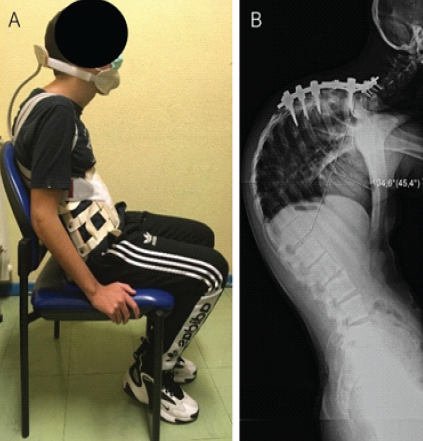

During the initial 2 months after surgery, the patient experienced improved posture and significant pain relief. However, at subsequent follow-up, he developed progressive back pain and radiographic evidence of loss of correction at the proximal junction. At 8 months postoperatively, imaging demonstrated an increased proximal junctional angle above the UIV, consistent with PJK (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: (a) Examination showing prominent upper back kyphosis at the cervicothoracic spine junction; and (b and c) 8-month post-operative spine lateral view radiographs showing a proximal junctional kyphosis.

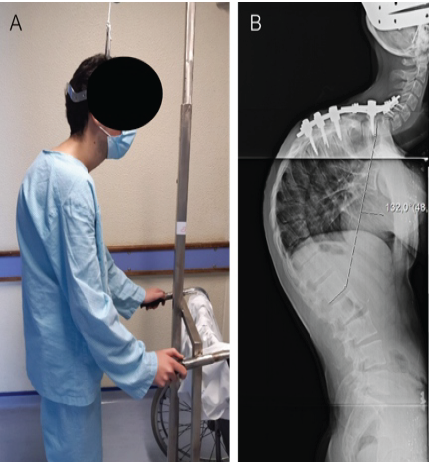

Eleven months after the index procedure, a revision surgery was performed, extending the fixation to the cervicothoracic junction (C5–T5) and removing the distal thoracolumbar instrumentation. Three weeks later, the patient developed signs of acute post-operative infection. Cultures confirmed Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-sensitive), which was successfully managed with a 3-week course of intravenous flucloxacillin, surgical debridement and wound revision, followed by 10 weeks of oral cotrimoxazole and rifampin. Despite infection resolution, subsequent follow-up radiographs demonstrated recurrent and rapidly progressive thoracic kyphosis, with a Cobb angle increasing to 134°, indicating structural failure and loss of reduction at previously instrumented levels. Before surgical reintervention, a cervico-thoraco-lumbo-sacral orthosis – Milwaukee brace – was prescribed to provide external support and attempt to control further deformity progression (Fig. 4). Six months after the revision procedure, a third operation was performed, during which halo-gravitational traction was applied for 3 weeks with progressive loading from 5 to 10 kilograms (Fig. 5).

Figure 4: (a) Examination showing Milwaukee brace providing external support and (b) full-length lateral spine radiograph with a thoracic kyphosis measured at 134°.

Figure 5: (a) Clinical picture at evaluation of patient with halo-gravitational traction and (b) full-length lateral radiograph of the spine demonstrating severe thoracic kyphosis with a Cobb angle measurement of 132°.

Following traction, the patient underwent a fourth and definitive procedure consisting of revision of the posterior instrumentation from C5 to L3, including pedicle screw fixation at L1–L3, Ponte osteotomies from T5 to T11 for sagittal realignment, deformity reduction using the cantilever technique and posterolateral fusion with autologous bone graft.

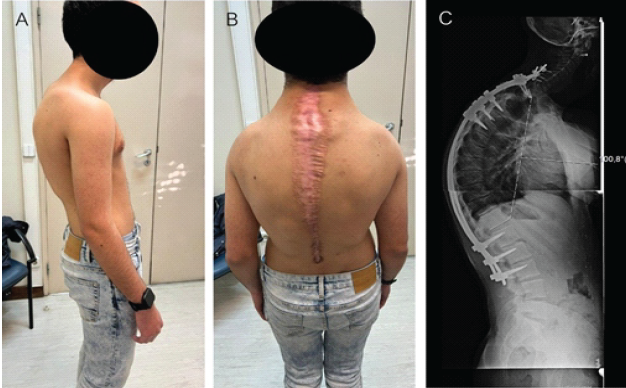

Follow-up and

Follow-up radiographs obtained 12 months after the revision procedure showed stable fusion with a Cobb angle of 100° and no evidence of further proximal junctional deterioration (Fig. 6). At 2 years postoperatively, the patient demonstrated marked improvement in posture, significant pain reduction and was able to resume swimming activities.

Figure 6: (a) Examination showing improvement regarding the upper back kyphosis, (b) surgical scar widening of the margins probably due to the underlying connective tissue laxity, and (c) follow-up radiographs at 12 months post-revision demonstrates a stable spinal fusion with a Cobb angle of 100°.

In this adolescent patient with genetically confirmed KS, a structural thoracic hyperkyphosis around 95° who is near skeletal maturity and symptomatic, operative correction would generally be considered an appropriate indication within contemporary kyphosis treatment paradigms. In contrast, non-operative measures, such as physiotherapy, bracing, and/or casting, are primarily recommended for moderate deformities in skeletally immature patients. For large, rigid curves approaching maturity, bracing is unlikely to achieve meaningful or durable radiographic correction and typically serves a supportive, symptom-modulating role rather than a deformity-correcting one [8,9]. In this case, the progress of thoracic deformity, development of PJK and the need for multiple revision procedures illustrates the convergence of several interrelated risk domains. These include syndrome-specific factors such as ligamentous laxity and immune dysfunction, mechanical and surgical risks related to instrumentation and correction techniques, and post-operative complications including infection and mechanical failure. Collectively, these highlight the importance of implementing targeted management strategies to reduce the risk of PJK and other post-operative complications. PJK is a well-recognized complication following long spinal fusions for adolescent spinal deformity, with reported prevalence ranging from 11% to 27% within 2–7 years postoperatively [10]. Its etiology is multifactorial, encompassing both patient-specific and surgical factors. Previously identified risk factors include advanced age, osteoporosis, pre-operative sagittal imbalance, excessive deformity correction, disruption of posterior ligamentous structures and poor paraspinal muscle quality. Radiographic and technical contributors, such as large pre-operative kyphosis, selection of the UIV, extensive osteotomies, use of rigid rod constructs and proximal soft-tissue disruption, further increase susceptibility to junctional failure. More recent studies emphasize the importance of preserving the proximal soft-tissue envelope, optimizing rod contouring and reinforcing the posterior ligamentous complex to mitigate junctional stress [11,12,13]. In the present case, several of these risk factors were present simultaneously. The patient’s severe pre-operative thoracic kyphosis of 95° imposed significant biomechanical demands and required an extensive correction, amplifying stresses at the UIV. The combination of multiple osteotomies and long-segment instrumentation increased the mechanical moment arm across the junctional region. The initial construct, consisting of pedicle screws at T5, T7, T11, T12, and L1 with transverse hooks at T2–T3, created a proximal transition zone at T2–T3, an area particularly vulnerable if soft-tissue preservation is suboptimal. The subsequent progression of the deformity to a Cobb angle of 134° indicates that mechanical failure, rather than a biological fusion issue alone, played a predominant role in the junctional collapse. KS is associated with generalized connective tissue abnormalities, including ligamentous laxity and joint hypermobility [1,14]. Such intrinsic laxity may compromise the stability of the posterior ligamentous complex, a key structure in maintaining proximal spinal integrity following instrumentation [13,15]. Although biomechanical vulnerability and reduced resistance to abnormal sagittal loading could theoretically predispose to PJK in this case, the available systematic reviews and meta-analyses do not list generalized joint hyperlaxity or syndromic hypermobility as independent predictors of PJK in spinal deformity populations [16,17]. This suggests that the role of ligamentous laxity may be under-recognized or under-studied in the context of spine surgery and further research may be needed to clarify any potential association. The interplay between post-operative infection and mechanical failure must also be considered. The onset of a post-operative spinal infection after the revision surgery contributed to biological compromise of fusion and structural integrity of the previous correction. Infection-related inflammation can impair bone and soft-tissue integrity, inhibit graft incorporation, increase the risk of nonunion and hardware loosening. In the setting of deformity correction, these changes may precipitate early junctional failure. Furthermore, KS is associated with immune dysfunction, particularly humoral immune defects such as hypogammaglobulinemia, low IgA/IgG levels, and reduced memory B cells and T-cell abnormalities, which confer increased susceptibility to recurrent infections [1,18]. Regardless of being an acute infection and effectively treated, this combination could have played an important role in the subsequent progressive thoracic kyphosis observed thereafter. Despite recognition of immune abnormalities in KS, robust data quantifying perioperative infection risk in this population is lacking. Nonetheless, pre-operative immunologic assessment and individualized perioperative planning should be considered to mitigate preventable complications. Given these multifactorial risk factors, meticulous surgical planning and technique are essential to minimize the risk of proximal PJK. Both existing literature and the present case support a prevention strategy that starts with early recognition of underlying connective-tissue disorders such as KS, as ligamentous laxity and soft-tissue fragility may increase junctional stress. Surgical goals should emphasize restoration of a physiologic sagittal profile without excessive correction and avoidance of junctional mismatch, alongside thoughtful UIV selection, preferably at a neutral/stable level and avoiding termination in a vulnerable transition zone. Preservation of the proximal posterior soft-tissue envelope is critical: during exposure and instrumentation, efforts should be made to minimize disruption around the UIV, preserving the posterior ligamentous complex and facet capsules at the top of the construct [12,13,19]. In addition, mitigating the proximal stiffness gradient can be considered in high-risk patients. Constructs with hooks provide a softer stress transition to the UIV and allow for less dissection of the surrounding muscle and facet [19,20]. In addition, rod contouring should reproduce the native sagittal alignment and avoid overcorrection or stiffness mismatch between rod and spinal curvature [13,19]. Finally, because junctional failure is not purely mechanical, biologic optimization remains essential: proactive infection prevention and early treatment, nutritional support and optimization of bone metabolism/fusion biology should be integrated into perioperative planning. In select high-risk cases, post-operative external support (bracing) may be used as an adjunct to reduce early junctional loading while fusion consolidates, recognizing that its preventive benefit is not uniformly established and should be individualized [21,22]. In this case, despite the complexity of the deformity and the occurrence of post-operative complications, a staged revision strategy that incorporated halo-gravitational traction before definitive fixation allowed gradual correction while minimizing neurological and mechanical stress. The final posterior fusion extending from C5 to L3 achieved satisfactory sagittal alignment and maintained stability without recurrence of PJK at 2-year follow-up. This outcome demonstrates that, even in syndromic patients at high risk for mechanical and infectious complications, a carefully staged, biomechanically sound and biologically optimized approach can yield favorable outcomes.

This case illustrates that patients with KS, with complex interplay of ligamentous laxity, immune dysfunction and skeletal anomalies, present unique challenges in spinal deformity surgery. The risk for PJK may be amplified by the confluence of soft-tissue weakness, aggressive correction and long-segment instrumentation. Recognition of these risk domains and tailored surgical strategies, including preservation of the posterior tension band, appropriate UIV selection and rod design, are essential to optimize outcomes. Further reporting of such syndromic cases in the literature will enhance our understanding of how best to apply these principles in rare but higher-risk patient populations.

In patients with Kabuki Syndrome the coexistence of ligamentous laxity, immune dysfunction, and severe spinal deformity creates a “perfect storm” for possible proximal junctional kyphosis after spinal fusion. Early recognition of these risks, preservation of the posterior ligamentous complex and cautious deformity correction are critical to achieving durable surgical outcomes.

References

- 1. Adam MP, Hannibal M. Kabuki syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62111/ [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Matsumoto N, Niikawa N. Kabuki make-up syndrome: A review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2003;117C:57-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Adam MP, Hudgins L. Kabuki syndrome: A review. Clin Genet 2005;67:209-19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Lee SM, Lee GW. The impact of generalized joint laxity on the clinical and radiological outcomes of single-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J 2015;15:809-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lovecchio F, Lafage R, Line B, Bess S, Shaffrey C, Kim HJ, et al. Optimizing the definition of proximal junctional kyphosis: A sensitivity analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2023;48:414-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Chen X, Chen ZH, Qiu Y, Zhu ZZ, Li S, Xu L, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis after posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion in young children with congenital scoliosis: A preliminary report on its incidence and risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:E1197-203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Lange T, Boeckenfoerde K, Gosheger G, Bockholt S, Bövingloh AS. Risk factor analysis for proximal junctional kyphosis in neuromuscular scoliosis: A single-center study. J Clin Med 2025;14:3646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Sebaaly A, Farjallah S, Kharrat K, Kreichati G, Daher M. Scheuermann’s kyphosis: Update on pathophysiology and surgical treatment. EFORT Open Rev 2022;7:782-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Arlet V, Schlenzka D. Scheuermann’s kyphosis: Surgical management. Eur Spine J 2005;14:817-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Yan C, Li Y, Yu Z. Prevalence and consequences of the proximal junctional kyphosis after spinal deformity surgery: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Boeckenfoerde K, Schulze Boevingloh A, Gosheger G, Bockholt S, Lampe LP, Lange T. Risk factors of proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis-the spinous processes and proximal rod contouring. J Clin Med 2022;11:6098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Zhong J, Cao K, Wang B, Li H, Zhou X, Xu X, et al. Incidence and risk factors for proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after correction surgery: A meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2019;125:e326-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Lee BJ, Bae SS, Choi HY, Park JH, Hyun SJ, Jo DJ, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis or failure after adult spinal deformity surgery – review of risk factors and its prevention. Neurospine 2023;20:863-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Schott DA, Stumpel CT, Klaassens M. Hypermobility in individuals with Kabuki syndrome: The effect of growth hormone treatment. Am J Med Genet A 2019;179:219-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kapetanakis S, Chatzivasiliadis M, Gkantsinikoudis N. Anatomy and biomechanics of posterior ligamentous complex of the human spine: A narrative review. Surg Radiol Anat 2025;47:170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Zhao J, Chen K, Zhai X, Chen K, Li M, Lu Y. Incidence and risk factors of proximal junctional kyphosis after internal fixation for adult spinal deformity: A systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev 2021;44:855-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Zou L, Liu J, Lu H. Characteristics and risk factors for proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity after correction surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev 2019;42:671-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Hoffman JD, Ciprero KL, Sullivan KE, Kaplan PB, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, et al. Immune abnormalities are a frequent manifestation of Kabuki syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2005;135:278-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Safaee MM, Osorio JA, Verma K, Bess S, Shaffrey CI, Smith JS, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis prevention strategies: A video technique guide. Oper Neurosurg 2017;13:581-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Baymurat AC, Yapar A, Tokgoz MA, Daldal I, Akcan YO, Senkoylu A. Using proximal hooks as a soft-landing strategy to prevent proximal junctional kyphosis in the surgical treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Turk Neurosurg 2024;34:505-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Shahi P, Merrill RK, Pajak A, Samuel JT, Akosman I, Clohisy JC, et al. Post-operative hyperextension bracing has the potential to reduce proximal junctional kyphosis: A propensity matched analysis of braced versus non-braced cohorts. Global Spine J 2025;15:1695-702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Kato S, Smith JS, Driesman D, Shaffrey CI, Lenke LG, Lewis SJ, et al. Post-operative bracing following adult spine deformity surgery: Results from the AO Spine surveillance of post-operative management of patients with adult spine deformity. PLoS One 2024;19:e0297541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]