Polyarticular septic arthritis with an atypical course should prompt evaluation for melioidosis, as early recognition and targeted antimicrobial therapy are essential to prevent dissemination and relapse.

Dr. Suraj Prakash, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, M.S Ramaiah Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: suraj.prakash2210@gmail.com

Introduction: Melioidosis is an infection caused by Burkholderia Pseudomallei, endemic to South East Asia and Northern Australia but rarely seen in the Indian subcontinent. Melioidosis causing polyarticular septic arthritis is an extremely rare entity. It must be kept as a differential diagnosis in endemic regions to provide early diagnosis and timely management to improve patient outcome.

Case Report: Here, we present the case of a 31-year-old man who presented with fever, abdominal, and significant weight loss since 2 months. He has long-standing diabetes mellitus and chronic alcohol abuse. He developed right elbow pain with painful range of motion 1 week into his hospital stay and was taken up for arthrotomy. One week post this, he developed right knee pain and restriction of movement. A positive synovial tissue histopathology examination showed B. pseudomallei. He achieved symptomatic improvement and disease control under ongoing eradication therapy.

Conclusion: This case throws light on a possibility of polyarticular septic arthritis caused by disseminated melioidosis. A rare but significant entity in endemic regions. While keeping melioidosis as a differential, early diagnosis and prompt treatment can provide favorable short-term outcome, though risk of relapse remains given ongoing therapy and limited follow-up.

Keywords: Septic arthritis, polyarticular, Burkholderia pseudomallei.

Septic arthritis is a common orthopedic emergency which causes significant mortality and morbidity. It is noted to have a case fatality rate of 5–15% and irreversible joint damage in 25–50% patients afflicted [1]. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species are the most common causative organism; however, Gram-negative organisms are known to cause septic arthritis mainly Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas spp. Melioidosis is a mostly fatal condition caused by Burkholderia Pseudomallei, an aerobic, non-fermenting, non-spore forming, facultative intracellular, and motile Gram-negative bacillus with classical “safety pin” appearance under the microscope. It strong resembles Pseudomonas spp. in microbiology laboratories and is commonly referred to as Whitmore’s disease or “The Great Mimicker of TB,” hence making it underdiagnosed and going underreported across the tropics including India [2]. Orthopedic manifestations of melioidosis, including septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, have been reviewed in the Indian context by Jain et al. [3]. Patients usually have splenic, liver, and parotid abscesses with fever and weight loss. About 50% of patients have diabetes. It is also associated with excess alcohol consumption, chronic liver, and renal diseases and thalassemia [4]. No association with human immunodeficiency virus has been reported yet [5]. A 20-year prospective study in Australia showed a significant difference in case fatality rates for melioidosis. Patients experiencing septic shock had a 50% fatality rate, whereas those without septic shock had a much lower fatality rate of 4% [6]. B. Pseudomallei causing septic arthritis is a rare entity. B. pseudomallei was listed as a category B bio-threat agent by the center for disease control and prevention in 2002 due to its potential to cause life-threatening airborne infections and its limited therapeutic alternatives [7]. The estimated global burden of melioidosis in 2019 in terms of disability adjusted life years was 4.64 million [2]. Melioidosis mainly affects people of poor socioeconomic background in low and middle income countries [2]. Orthopedic manifestations of melioidosis, including septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, have been reviewed in the Indian context by Deb et al. However, ipsilateral polyarticular septic arthritis remains extremely rare, underscoring the need for continued reporting of such unusual presentations [1]. Here, we present the case of a 31-year-old male presenting with systemic features melioidosis and later developing ipsilateral poly-articular septic arthritis of the right knee and elbow 1 week part in the hospital setting.

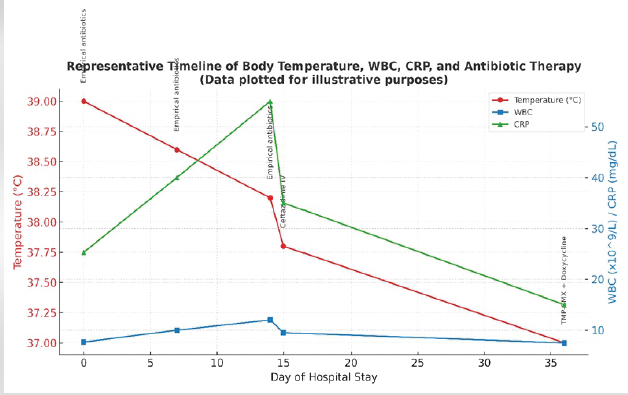

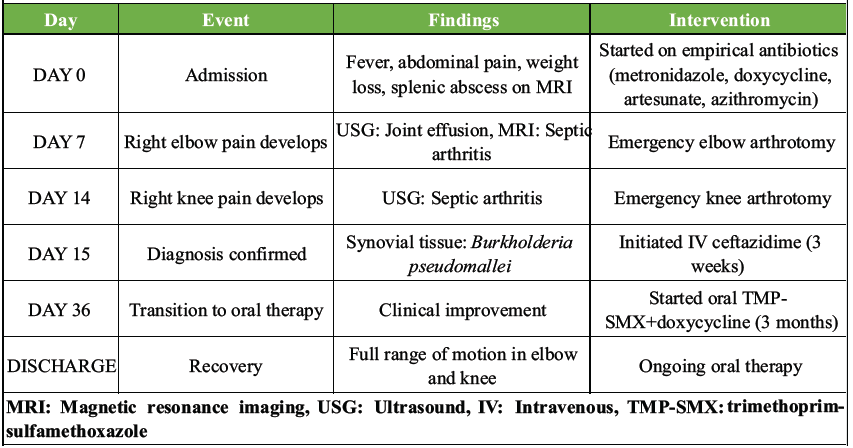

A 31-year-old male patient, a resident of Tamil Nadu, came to the general medicine outpatient department with complaints of fever, right hypochondrial pain, and weight loss of 14 kg in the last 2 months. The patient was a resident of Tamil Nadu, a region where melioidosis has been increasingly reported. In this setting, percutaneous inoculation through skin exposure to contaminated soil or water, particularly during the monsoon season, is considered a common route of infection. Percutaneous entry remains a likely route of infection in this case [8,9]. He is a known diabetic since the age of 5 and is insulin dependent. He has a history of consuming alcohol since past 12 years (Consumes 300 mL of Rum/week for 11 years). He has a history of 6 pack years of smoking tobacco. He had no significant travel history to endemic regions. His reports showed hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL, total leucocyte count of 7660, and platelet count of 59,000. Glucose 2+ in urine routine and C-reactive protein 25.35 mg/dL (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1: Representative timeline of body temperature, white blood cells, C-reactive protein, and antibiotic therapy.

Table 1: Laboratory parameters at presentation

Cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test and GeneXpert Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB/rifampicin) assay, performed to detect MTB, were both negative. Chest X-ray showed bilateral infiltrates in the lower lobes with the left costophrenic angle blunting. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abdomen and pelvis showed an enlarged spleen with an abscess measuring 2.9 cm × 2.3 cm × 2.6 cm in the inferior aspect. Serial blood cultures showed no growth. The patient was started on empirical antibiotic treatment, that is, metronidazole, doxycycline, artesunate, and azithromycin. The presence of multiple splenic abscesses in a diabetic patient from a melioidosis-endemic region should have raised early suspicion for B. pseudomallei. Splenic and hepatic abscesses are well-documented in disseminated melioidosis, particularly in those with diabetes and chronic alcohol use. However, the initial antimicrobial regimen – metronidazole, doxycycline, artesunate, and azithromycin – did not cover B. pseudomallei, delaying targeted therapy. The patient developed right elbow swelling (Fig. 2), sudden in onset, dull aching type, non-progressive, and non-radiating with painful restriction of movements.

Figure 2: Right elbow swelling.

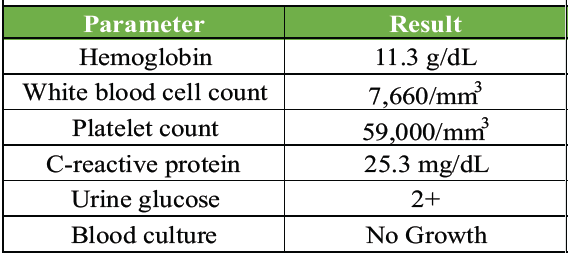

On clinical suspicion, ultrasound (USG) of the right elbow was done which showed a cystic lesion with thick internal echoes in the extensor and lateral aspect of the distal forearm measuring 3.6 × 1.3 × 2.8 cm with an approximal volume of 7.5 cc communicating with the elbow joint. MRI of the right elbow (Fig. 3) showed joint effusion with focal periarticular marrow edema in the proximal ulna concerning for inflammatory/infective arthritis.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging report of the right elbow joint.

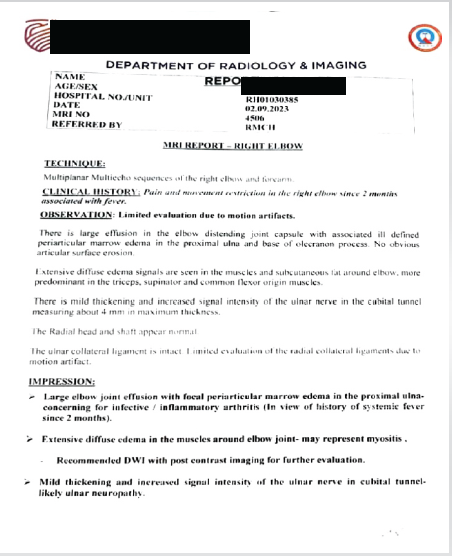

Patient underwent emergency right elbow arthrotomy and samples were sent for culture and sensitivity, Gram staining, and acid-fast bacillus (AFB). Gram stain showed Gram-negative bacilli. Empirical therapy was continued and patient’s elbow pain resolved with gradual improvement in his range of motion. One week later, orthopedics’ opinion was sought in view of the right knee swelling and pain with painful restriction of movement (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Clinical examination of affected joint.

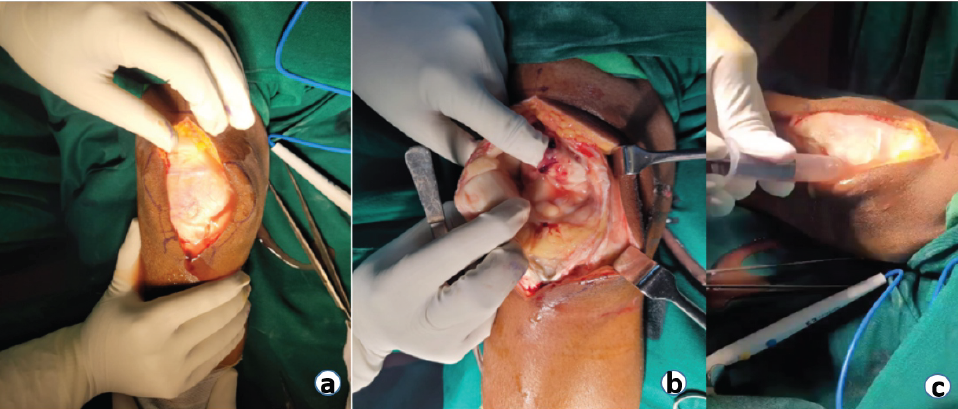

The pain was insidious in onset, dull aching type, non-radiating, aggravating on movement, and relieved with analgesics. Clinically, parapatellar fossa was full with patella tap test positive. Local rise of temperature with redness was noted. Knee joint was held in 30° flexion as the most comfortable position of the limb. USG of the right knee joint showed hypoechoic collection with internal echoes in the suprapatellar and posterior aspect of the femoral condyle, suggestive of septic arthritis. MRI was not sought in view of clear indication toward septic arthritis. Under aseptic precautions, knee joint was aspirated which revealed 10 mL of straw-colored fluid with a cell count of >50,000 cells/mm3 (80% neutrophils and 20% lymphocytes and plenty of degenerated synoviocytes). The patient was then taken up for emergency right knee arthrotomy (Fig. 5a, b, c). Samples were sent for culture and sensitivity, Gram stain, and AFB and showed short bipolar stained Gram-negative bacillus with “uneven staining.” Synovial tissue sample collected intra-operatively showed oxidase positive, Gram-negative bacillus further identified as B. Pseudomallei.

Figure 5: (a, b, c) Intraoperative pictures of the right knee arthrotomy.

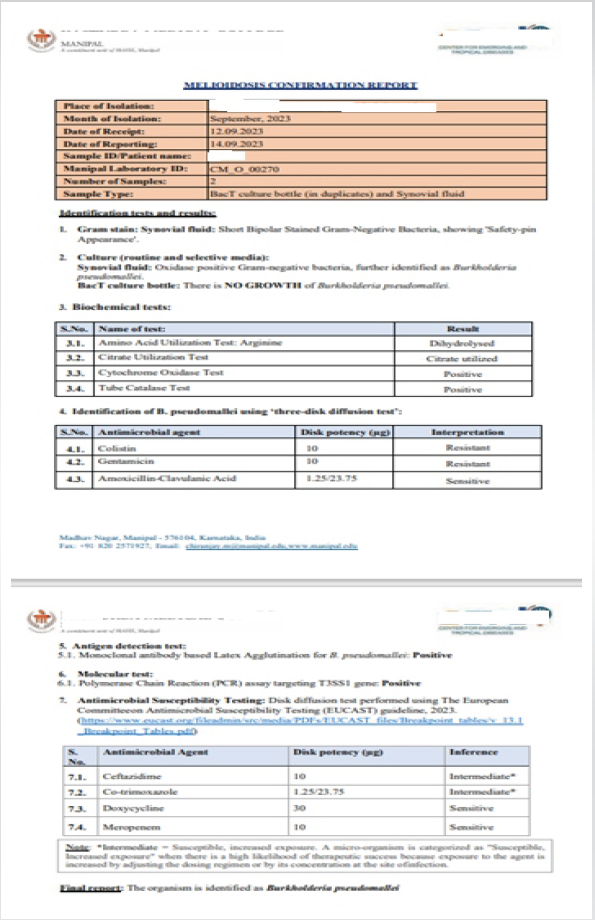

The elbow was approached through a standard lateral incision, and the knee through a medial parapatellar approach. Turbid synovial fluid and inflamed synovium were encountered in both joints. Thorough synovectomy and lavage were carried out using approximately 9 L of normal saline until clear effluent was obtained. Intraoperative tissue and fluid samples were collected for microbiological examination before resumption of antibiotics. Closed suction drains were placed and removed after 48 h once drainage had subsided. Early physiotherapy was initiated to prevent stiffness, and range of motion gradually improved over subsequent follow-up. Synovial fluid and synovial tissue samples obtained during elbow and knee arthrotomy were processed at a reference microbiology laboratory (Center for Emerging and Tropical Diseases, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal). Gram staining demonstrated short, bipolar, safety-pin–appearing Gram-negative bacilli. Culture on selective media yielded oxidase-positive colonies identified as B. pseudomallei based on characteristic biochemical reactions including arginine dihydrolysis, citrate utilization, cytochrome oxidase positivity, and catalase positivity. Identification was further confirmed by latex agglutination for B. pseudomallei and polymerase chain reaction detecting the T3SS1 gene, establishing the diagnosis with high specificity [Fig. 6].

Figure 6: Melioidosis confirmation report.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing performed using the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) 2023 guideline demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to ceftazidime and co-trimoxazole, and sensitivity to doxycycline and meropenem. The BacT culture bottle showed no growth, indicating localized infection without bacteremia. Despite negative blood cultures, the patient exhibited involvement of multiple joints and splenic abscesses on imaging, fulfilling the Darwin criteria for disseminated melioidosis.

The diagnosis was, therefore, established as polyarticular septic arthritis due to disseminated B. pseudomallei infection.

Monoclonal antibody-based latex agglutination (MLA), specifically the Mahidol latex agglutination test, was performed directly on synovial fluid for the rapid detection of B. pseudomallei. This assay, which detects the capsular polysaccharide antigen, is widely used in endemic regions due to its high specificity. Conducting MLA on a clinical sample rather than a bacterial isolate enables early diagnosis and prompts initiation of appropriate therapy, though its sensitivity may vary with bacterial load.

Disk diffusion test performed using the EUCAST guideline, 2023 showed intermediate susceptibility to ceftazidime and co-trimoxazole and sensitive to doxycycline and meropenem. Patient was then started on the initial intensive phase where intravenous (IV) ceftazidime 2g IV (TID) given for a period of 3 weeks. Subsequently eradication therapy of 3 months consisting a combination of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg – trimethoprim 160 mg and doxycycline 100 mg was administered to the patient. This is in accordance with the “2024 Darwin Melioidosis Treatment Guidelines” which provides updated recommendations for the management of melioidosis, emphasizing prolonged antimicrobial therapy to prevent relapse (Table 2).

Table 2: Summary of clinical course

Although meropenem demonstrated higher in vitro sensitivity, ceftazidime was continued as the intensive-phase agent in line with the 2024 Darwin Melioidosis Guidelines, which consider both drugs acceptable based on clinical stability and resource availability The patient showed significant improvement in general condition and was restored to full painless range of movements of his right elbow and knee. The patient was discharged after completing the intensive phase of IV antibiotics and was advised to continue the oral eradication regimen under outpatient supervision. Subsequent clinical follow-up could not be undertaken beyond this period due to loss to follow-up. Based on available records, there was no documented recurrence or systemic relapse at the time of last contact. Long-term surveillance was recommended in view of the known relapse risk associated with melioidosis.

Melioidosis is a potentially fatal disease caused by B. pseudomallei, an aerobic, non-fermenting, non-spore-forming, facultative intracellular, and motile Gram-negative bacillus that exhibits uneven staining under the microscope [10]. The bacterium is commonly found in soil and surface water in endemic regions and can infect humans through direct inoculation, inhalation, or ingestion. Although musculoskeletal involvement in melioidosis is uncommon, it has been well documented. A study by Gouse et al., which analyzed 163 patients with culture-confirmed melioidosis, found that 14.7% had musculoskeletal manifestations [11]. Risk factors and latency in melioidosis disproportionately affects individuals with predisposing conditions such as diabetes mellitus (23–60%), heavy alcohol use (12–39%), chronic pulmonary disease (12–27%), chronic renal disease (10–27%), thalassemia (7%), and glucocorticoid therapy (<5%) [4]. Notably, not all individuals exposed to B. pseudomallei develop clinical disease, suggesting that host immunity plays a significant role in pathogenesis. While B. pseudomallei has been reported to persist in a latent state, recent phylogenetic studies indicate that extreme latency beyond a decade is rare. The previously cited 62-year latency period, often associated with Vietnam War veterans, has been disputed by newer research, suggest that cases attributed to prolonged dormancy may, in fact, represent reinfection rather than true reactivation. This raises critical questions regarding the mechanisms of long-term bacterial persistence and relapse, emphasizing the need for further research [12]. Pathogenesis and bone-joint involvement. Patients with primary skin or soft-tissue infections in melioidosis appear to have better survival rates upon hospitalization [5]. However, delays in diagnosis exceeding 2 weeks have been identified as a significant risk factor for osteoarticular involvement [4]. In native joints, bacterial arthritis is typically a consequence of hematogenous seeding from transient or persistent bacteremia [13]. A key virulence factor of B. pseudomallei is its Type III Secretion System (TTSS), which consists of three gene clusters that function as molecular syringes, injecting bacterial effector proteins into host cells. Among these, the TTSS3 (Inv/Mxi-Spa-type system) plays a crucial role in intracellular survival and immune evasion, enabling the pathogen to persist and cause systemic dissemination [4]. Although TTSS is a fundamental mechanism in melioidosis pathogenesis, its direct relevance to septic arthritis remains unclear in this case. Visceral abscess management splenic abscess is a rare but serious condition traditionally managed with percutaneous drainage or splenectomy. However, recent studies suggest that small abscesses can often be treated successfully with antibiotics alone. Liu et al. (2000) reported that splenic abscesses smaller than 4 cm may resolve with conservative therapy. Similar findings were described by Fombuena Moreno et al., and Alnasser et al., who all documented successful outcomes with antibiotics alone [14,15]. In this case, the 2.9 cm splenic abscess resolved with antibiotic therapy alone. No formal radiological follow-up was performed; however, the patient remained asymptomatic on clinical evaluation. This supports the growing evidence that small splenic abscesses can be effectively managed without invasive procedures when closely monitored. Epidemiology and diagnostic challenges despite being endemic to Southeast Asia and Northern Australia, melioidosis remains underreported in India, likely due to low clinical suspicion and limited diagnostic infrastructure. The highest number of annual melioidosis cases – nearly 600 – was reported in 2021 [2]. However, it remains unclear whether this increase reflects a true rise in incidence, enhanced surveillance, or improved diagnostic capabilities. India’s growing case burden underscores the need for heightened awareness and early consideration of melioidosis as a differential diagnosis, especially in febrile patients with unexplained visceral abscesses and osteoarticular involvement. A genomic study of 469 B. pseudomallei isolates from 30 countries over 79 years found that melioidosis is highly endemic in Southeast Asia and northern Australia but rare in East Asia (including South Korea and Japan), where cases are mostly sporadic and imported. The data suggest that Australia was an early reservoir, with the bacteria later spreading to Southeast and South Asia. However, East Asia shows no evidence of sustained local transmission or outbreaks, indicating a very low risk of melioidosis in this region compared to endemic areas [16]. Implications for travel medicine travelers to melioidosis-endemic areas should avoid soil and stagnant water, especially those with diabetes, kidney disease, or weakened immunity. Wearing protective footwear and gloves during outdoor activities, particularly in the rainy season, are critical. High-risk individuals should seek pre-travel medical advice, as no vaccines exist. Symptoms may appear weeks or months post-exposure, requiring prompt medical care if fever, pneumonia, or sepsis occurs. Suspected cases need biosafety level 3 handling, and heightened awareness among travelers and doctors is vital for early detection and treatment [17]. For non-endemic areas, the latest literature emphasizes several key strategies to address the emerging risk of melioidosis. Healthcare professionals should maintain a high index of suspicion for melioidosis in patients presenting with fever, pneumonia, or sepsis who have traveled to or lived in endemic regions, as a diagnostic delays of up to 18 months have been reported and can be fatal. Strengthening laboratory capacity to identify B. pseudomallei is crucial, as misdiagnosis is common and can hinder timely treatment. Public health authorities should implement surveillance systems to detect imported or locally acquired cases, especially as climate change and global trade increase the risk of introduction through severe weather events, imported animals, or contaminated products. Finally, biosafety protocols should be in place for handling clinical specimens, as B. pseudomallei poses a laboratory infection risk [18]. Clinical significance of this case melioidosis presenting as monoarticular septic arthritis is well documented and orthopedic manifestations 197 have been comprehensively described in Indian literature by Jain et al. [3]. However, ipsilateral polyarticular septic arthritis due to B. pseudomallei remains extremely rare, making our case noteworthy. Such cases are often misdiagnosed as tuberculosis, further complicating early recognition and management. Treatment considerations and relapse risk. The 2024 Darwin Melioidosis Treatment Guidelines recommend at least 10–14 days of IV ceftazidime or meropenem, followed by oral eradication therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP+SMX) and doxycycline for 3–6 months (Currie et al., 2023). Despite a favorable outcome in this case, the patient’s treatment duration was shorter than recommended, raising concerns about potential relapse. The 2024 revision of the Darwin Melioidosis Treatment Guideline introduces several practical and clinically significant changes aimed at improving treatment safety and effectiveness [19]. First, the guideline now recommends a graded introduction of TMP+SMX to minimize adverse effects. Rather than commencing full doses immediately, patients are gradually escalated to the target dose over several days. This approach is adjusted based on patient weight and kidney function, though patients with neurological melioidosis should still start on full-dose therapy straight away. Second, the guideline strengthens adverse effect monitoring during prolonged TMP+SMX therapy. Monthly clinical reviews and blood tests, including kidney and liver function, full blood counts, and inflammatory markers, are now considered essential to detect complications such as acute kidney injury, bone marrow suppression, and severe skin reactions. Treatment durations have also been more clearly defined based on infection site and disease severity: Simple skin abscesses and cases of bacteremia without a clear focus now require a minimum of 2 weeks of IV antibiotics, followed by 3 months of oral therapy. More severe presentations, such as multilobar pneumonia or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, require extended IV therapy, up to 4 weeks, with a standard 3-month oral phase. Infections involving the central nervous system or vascular structures necessitate at least 8 weeks of IV treatment, followed by 6 months of oral therapy, with the possibility of lifelong suppressive treatment if prosthetic material is involved. Prophylactic TMP+SMX is also recommended in specific high-risk groups, including dialysis patients during the wet season and individuals receiving selected immunosuppressive therapies. Finally, the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor is now routinely considered in ICU patients with septic shock to support immune recovery, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is recognized as a life-saving option in critically ill patients with refractory disease.

Management of our case

According to the Darwin Melioidosis Treatment Guideline (2024), ceftazidime or meropenem are recommended as first-line IV antibiotics. In this case, ceftazidime 2 g every 8 h was used, but drug sensitivity testing later showed intermediate susceptibility. Meropenem, which was sensitive, may have been a more optimal choice. For the oral eradication phase, the patient was prescribed sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (TMP 160 mg + SMX 800 mg, twice daily) and doxycycline 100 mg twice. Although the EUCAST report demonstrated intermediate susceptibility to ceftazidime and higher sensitivity to meropenem, IV ceftazidime was selected as the intensive-phase agent in accordance with the 2024 Darwin Melioidosis Guidelines, which recommend either ceftazidime or meropenem depending on patient stability and resource availability. The patient responded clinically with resolution of fever, decreasing inflammatory markers, and improved joint mobility by the 3rd week. The subsequent oral eradication phase with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline for 3 months followed the standard Darwin protocol. Resource constraints and clinical improvement guided the decision to conclude eradication therapy at 3 months, with ongoing follow-up to monitor for relapse. The patient was prescribed oral trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP 160 mg + SMX 800 mg, twice daily), providing a total trimethoprim dose of 640 mg/day. This corresponds to approximately 10 mg/kg/day for a body weight of 64 kg, which was the patient’s weight at presentation. This dosage falls within the recommended therapeutic range of 8–12 mg/kg/day for severe disseminated melioidosis, ensuring adequate drug exposure in line with the EUCAST “susceptible, increased exposure” category. IV ceftazidime was administered at 6 g/day (2 g every 8 h) in accordance with the guidelines in effect at the time, although the 2024 Darwin Melioidosis Guidelines now recommend 8 g/day (2 g every 6 h) for severe disease.

Orthopedic implications

The 2024 Darwin Melioidosis Treatment Guideline highlights key considerations for managing bone and joint infections. Osteomyelitis requires at least 6 weeks of IV therapy, while septic arthritis and deep-seated collections need a minimum of 4 weeks, with both followed by at least 6 months of oral eradication therapy. Surgical drainage and debridement remain essential, and treatment timelines reset after each procedure. Although B. pseudomallei is recognized as a Category B bio-threat agent due to its potential for airborne transmission in laboratory settings, there are currently no reported cases of clinical transmission through surgical smoke or exposure to bodily fluids during surgical procedures. Laboratory exposures typically occur in the absence of primary containment or during aerosol-generating processes (Clay et al., 2022); (Speiser et al., 2023) [20,21]. Nevertheless, strict surgical precautions, including appropriate protective equipment and smoke evacuation systems, remain advisable to minimize theoretical risks. Close monitoring is necessary to detect recurrence, especially in complex or prolonged infections. Although antimicrobial resistance is rare, it may develop in cases with high bacterial burden or incomplete clearance. Long-term suppressive therapy is recommended when prosthetic joints or vascular grafts are involved. The guideline reinforces the need for a multidisciplinary approach involving orthopedic, infectious disease, and critical care teams for optimal management. Studies indicate that 10% of patients relapse even after 20 weeks of treatment, with relapse rates increasing to 30% if the treatment duration is <8 weeks [22]. This highlights the critical importance of adherence to prolonged eradication therapy to prevent recurrence.

Melioidosis should be strongly considered as a differential diagnosis in patients with septic arthritis, osteoarticular infections, and systemic manifestations, particularly in endemic regions. Given the potential for misdiagnosis as tuberculosis, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion and initiate early targeted therapy based on clinical suspicion, even before microbiological confirmation. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate antimicrobial therapy are crucial in reducing mortality and morbidity associated with this emerging infectious disease.

Disseminated melioidosis can present with polyarticular septic arthritis mimicking ordinary bacterial infections. Early identification and appropriate antibiotic therapy remain key to preventing relapse and mortality.

References

- 1. Deb S, Singh M, Choudhary J, Jain VK, Kumar S. A rare case of a knee septic arthritis by Burkholderia pseudomallei: A case report from a tertiary care hospital of Andaman and Nicobar island. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:20-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Mohapatra PR, Mishra B. Burden of melioidosis in India and South Asia: Challenges and ways forward. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 2022;2:100004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Jain VK, Jain D, Kataria H, Shukla A, Arya RK, Mittal D. Melioidosis: A review of orthopedic manifestations, clinical features, diagnosis and management. Indian J Med Sci 2007;61:580-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1035-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Parija D, Kar BK, Das P, Mishra JK, Agrawal AC, Yadav SK. Septic arthritis of knee due to Burkholderia pseudomallei: A case report. Trop Doct 2020;50:254-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Prasad R, Pokhrel NB, Uprety S, Kharel H. Systemic melioidosis with acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis misdiagnosed as tuberculosis: A case report. Cureus 2020;12:e7011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Peacock SJ, Schweizer HP, Dance DA, Smith TL, Gee JE, Wuthiekanun V, et al. Management of accidental laboratory exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:e2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Ganesan V, Sundaramoorthy R, Subramanian S. Melioidosis-series of seven cases from Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23:149-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Shaw T, Tellapragada C, Kamath A, Eshwara V, Mukhopadhyay C. Implications of environmental and pathogen-specific determinants on clinical presentations and disease outcome in melioidosis patients. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019;13:e0007312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Shetty RP, Mathew M, Smith J, Morse LP, Mehta JA, Currie BJ. Management of melioidosis osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:277-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Gouse M, Jayasankar V, Patole S, Veeraraghavan B, Nithyananth M. Clinical outcomes in musculoskeletal involvement of Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. Clin Orthop Surg 2017;9:386-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Hoffmaster A, AuCoin D, Baccam P, Baggett HC, Baird R, Bhengsri S, et al. Melioidosis diagnostic workshop, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2015;21:e141045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. González-Sanz M, Blair BM, Norman FF, Chamorro-Tojeiro S, Chen L. The evolving global epidemiology of human melioidosis: A narrative review. Pathogens 2024;13:926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Fombuena Moreno M, Mínguez Gómez C, Fernández Salinas M, Salavert Lletí M. Splenic abscess following gynecologic infection with complete response to antibiotic treatment. Infection 1995;23:324-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Alnasser SA, Alkhalaf AN, Alshahrani AA, Alothman AA, Alqahtani AA. Successful conservative management of a large splenic abscess with antibiotics alone in a patient with aortic valve infective endocarditis. Ann Med Surg 2019;45:75-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Chewapreecha C, Holden MT, Vehkala M, Välimäki N, Yang Z, Harris SR, et al. Global and regional dissemination and evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat Microbiol 2017;2:16263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Norman FF, Chen LH. Travel-associated melioidosis: A narrative review. J Travel Med 2023;30:taad039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. González-Sanz M, Blair BM, Norman FF, Chamorro-Tojeiro S, Chen L. The evolving global epidemiology of human melioidosis: A narrative review. Pathogens 2024;13:926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Currie BJ, Janson S, Meumann E, Martin GE, Ewin T, Marshal CS. The 2024 revised Darwin melioidosis treatment guideline. North Territ Dis Control Bull 2023;30: 3-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Clay LA, Straub KW, Adrianos SL, Daniels J, Blackwell JL, Bryant LT, et al. Monitoring laboratory occupational exposures to Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl Biosaf 2022;27:84-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Speiser LJ, Kasule S, Hall CM, Sahl JW, Wagner DM, Saling C, et al. A case of Burkholderia pseudomallei mycotic aneurysm linked to exposure in the Caribbean via whole-genome sequencing. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022;9:ofac136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Chien JM, Saffari SE, Tan AL, Tan TT. Factors affecting clinical outcomes in the management of melioidosis in Singapore: A 16-year case series. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]