Temporomandibular joint degeneration is highly prevalent but often overlooked in rheumatoid arthritis, and this study demonstrates that combining cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and musculoskeletal ultrasound offers the most comprehensive and accurate evaluation by capturing both detailed osseous destruction and active soft-tissue inflammation. CBCT excels in detecting cortical erosions, osteophytes, subchondral cysts, and joint space narrowing, whereas musculoskeletal ultrasound is superior for identifying synovitis, vascularity on Doppler, joint effusion, and dynamic disc pathology. The strong intermodality agreement supports their complementary use, highlighting that dual-modality imaging greatly enhances diagnostic precision, allows early detection of subclinical temporomandibular joint involvement, and facilitates timely, targeted interventions to prevent irreversible deformity and functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Dr. Ashwini Dhopte Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Chhattisgarh Dental College and Research Institute, Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh, India. Email: ashwinidhopte@gmail.com

Introduction: Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease and often affects the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), causing progressive degenerative alterations that severely affect the quality of life of the patients, their mastication, and their general functional abilities. TMJ has not been adequately studied as a clinical aspect of RA despite the fact that it may occur in the earliest stages of the disease, with a few symptoms, and because no specific surveillance guidelines have been put in place. The timely prevention of degenerative alterations with timely therapeutic responses and the most effective imaging options to holistically evaluate TMJ are a highly debated subject of rheumatological and dental medicine.

Materials and Methods: Sixty RA patients with the American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism 2010 classification criteria and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy people without TMJ disorders or systemic inflammatory conditions were enrolled in this cross-sectional control study. TMJ bilateral measures were conducted using standardized cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) measures to assess the changes in the bone including erosions, osteophytes, cysts in the subchondral area and joint space width (JSW) measurement, and the musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSKUS) examination that measured the soft-tissue pathology of joint effusion, synovial hypertrophy and the associated vascularity, and the erosion of the articular disc. These statistical analyses consisted of independent t-tests when comparing continuous variables, Chi-square when comparing categorical variables, and Cohen’s kappa coefficient when measuring inter-observer and intermodality agreement.

Results: RA patients exhibited much more prevalent rates of osseous degenerative alterations than in healthy controls: Cortical erosions (68.3% vs. 10.0%, P < 0.001), osteophytes (45.0% vs. 6.7%, P < 0.001), subchondral cysts (31.7% vs. 3.3% P = 0.002) and significantly smaller mean JSW (1.8 0.5 mm vs. 2.5) similar pathological alterations of the soft tissue were also frequent among the RA cohort: Joint effusion (71.7% vs. 16.7, P = 0.001), active synovitis with Doppler signal (63.3% vs. 13.3, P = 0.001), and anterior displacement of the disc (38.3% vs. 10.0, P = 0.004). CBCT and MSKUS had a high intermodal consensus when it comes to detecting erosion (K = 0.75) and moderate consensus when detecting synovitis (K = 0.62).

Conclusion: CBCT and MSKUS are useful in detecting different but complementary features of TMJ degeneration in RA patients, with the former being the best in revealing the detailed presence of the changes in the surroundings in a more detailed way, and the latter being the best in identifying and characterizing the presence of soft-tissue pathology and active inflammation. The combination of both modalities greatly improves diagnostic accuracy of the whole process of assessment and has more overall joint evaluation, which in turn benefits the evidence-based clinical decision-making and timely management intervention in patients with RA with TMJ involvement.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, temporomandibular joint, cone-beam computed tomography, musculoskeletal ultrasound, joint degeneration, diagnostic imaging, erosive arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disorder that occurs as a chronic progressive autoimmune disorder, which is essentially marked by the presence of sustained inflammation of the synovium, the formation of pannus, and the subsequent progressive destruction of the articular cartilage and underlying bone structures [1]. Although RA most commonly affects peripheral joints, hands, wrists, and feet, which are the classical manifestations of the disease, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is often affected as well, and various population groups of interest have been reported with a range of prevalence rates of 5% to 86% basing the prevalence rates on the diagnostic criteria, imaging techniques used, and the duration of the disease [2]. This broad spectrum of reported engagement highlights the difficulty in identifying TMJ pathology, as an early degenerative alteration is usually clinically inexpressible or has some non-specific clinical features that can be ignored during routine rheumatological evaluation. TMJ involvement in RA is clinically manifested in local pain and tenderness in the area of the preauricles, limited mouth opening (trismus), clicking or crepitation of the jaw movements, inability to adequately masticate food, and progressive dysfunction of the mandible, all of which all lead to severe loss in the nutritional intake, or speech articulation, and quality of life in patients [3]. Moreover, the untreated TMJ degeneration may cause serious complications such as mandibular micrognathia, anterior open bite, and total ankylosis in the severe stage, especially when the disease occurs during the skeletal growth stages in cases of juvenile RA patients. Thus, it is important to identify and monitor degenerative alterations of the TMJ at an initial stage in order to introduce timely treatment procedures that may help to retain the functionality of the joint and avoid irreversible structural changes. Conventional imaging methods, especially conventional panoramic radiography and transcranial projections, have proved insensitive to reveal early TMJ degenerative alterations, at least small cortical erosions, early cartilage degeneration, and soft-tissue pathology such as synovitis and joint effusion [4]. The drawbacks associated with these traditional two-dimensional methods are the intrinsic limitations, such as anatomical overlapping of surrounding structures, geometric distortion, and failure to visualize soft tissues, and as such require the use of more improved three-dimensional imaging modalities in order to give a comprehensive TMJ assessment. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has become one of the most useful imaging modalities that has a high level of detail, three-dimensional imaging of the structure of the bones at a better spatial resolution than is found with conventional radiography, and has considerably lower radiation doses than conventional multidetector computed tomography, and is especially well-suited to imaging in the head and neck [5]. CBCT allows the accurate measurement of cortical erosions, osteophytes, the development of subchondral cysts, condylar flattening, and accurate quantification of narrowing of the joint space, which are all the most important characteristics of degenerative TMJ disease in RA patients. Recent studies have also indicated that CBCT is particularly effective in identifying bony TMJ alterations in the RA cohort with erosion rates as high as 70% among the symptomatic patients [6]. Musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSKUS), on the other hand, is a radiation-free, inexpensive, and commonly available imaging modality, which allows real-time, dynamic imaging of the structures of soft tissues, synovial inflammation, joint effusion, and changes in the vascularity via the use of the power Doppler imaging without subjecting the patient to ionizing radiation [7]. MSKUS has been thoroughly tested and shown to be highly sensitive and specific when identifying synovitis, tenosynovitis, as well as erosions at peripheral joints in RA patients, and as a result, it has been integrated into the present European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) imaging guidelines in diagnosing and monitoring RA [8]. Nevertheless, even though MSKUS has demonstrated the usefulness in the evaluation of peripheral joints, its use as an evaluation tool in TMJ in RA has not been extensively studied, and there are a limited number of standardized scanning guidelines, as well as a limited amount of comparative data with existing imaging methods. Recent publications have started to point out the better capacity of CBCT to identify the presence of changes in the bone of the TMJ of the RA population; some reports have indicated a prevalence of erosion of over 70% of patients already with known disease [6]. At the same time, there is emerging evidence that MSKUS is quite sensitive and can detect synovial inflammation and effusion in the TMJ, but its diagnostic features and best scanning methodology need further confirmation [9]. Although these are optimistic data, an acute gap exists in the modern literature on systematic comparative evaluations of CBCT and MSKUS in terms of complete TMJ evaluation in patients with RA. Most of the literature reviewed has examined individual imaging modalities alone, thus not considering the possible complementary value of combined imaging modalities and not determining inter-modality congruency of individual pathologic features [10]. Moreover, limited population-specific information describing the co-occurring use of CBCT and MSKUS in the TMJ evaluation is also limited and therefore restricts the creation of evidence-based clinical interventions in the standardized TMJ surveillance protocols in the management of RA. This lack of comparative data is a major impediment to maximizing the imaging strategies in relation to TMJ implications with RA. The current research will fill these knowledge gaps, but the major aim of the study was to assess the degree, nature, and trends of TMJ degeneration in RA patients using both CBCT and MSKUS imaging systems. The secondary objectives were as follows: (1) Comparing imaging findings in RA patients and age- and sex-matched healthy controls in a systematically manner to identify disease specific patterns, (2) to find out inter-modality diagnostic concordance and agreement to particular pathological features, (3) determine the comparative strengths and limitations of each of the imaging modalities in particular types of TMJ pathology, and (4) give evidence-based recommendations as to how to integrate these imaging modalities with clinical practice to provide greater TMJ surveillance in RA population.

Study design and setting

The calculation of the sample size was made a priori with the G + Power program version 3.1.9.7 (Heinrich-Heine-Universitat Dusseldorf, Germany) with the following parameters: Type I error probability (0.05), statistic power (1-0.90) and a predicted medium-large effect size (Cohen d 0.50) based on preliminary data of the research conducted with the use of TMJ changes in RA groups. The calculation showed that the group required a minimum sample size of 54 participants to be used. To ensure sufficient statistical power to conduct the main outcome comparisons, we decided to recruit 60 RA patients and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls, accounting for an expected rate of 15% attrition because of the potential imaging artifacts, incomplete tests, or dropout of participants.

Ethical clearance was taken from the Institute of Rama Dental College with ethical clearance number 02/IEC/RDCHRC/2023-2024/194, approved on August 16th, 2023.

Participant selection

RA patient group (n = 60)

Recruitment of the patients occurred in a systematic sampling of the outpatient rheumatology clinic of the institution. Inclusion criteria included: (1) Adults between the ages of 18 and 70 years, (2) a definitive diagnosis of RA that meets the American College of Rheumatology/EULAR 2010 classification criteria, (3) a disease duration of at least 6 months since initial diagnosis, (4) either the presence of TMJ-related symptoms (pain, clicking, locking, or restricted mouth opening) or asymptomatic patients that agree to undergo bilateral TMJ imaging assessment. The patients were selected without any emphasis on their disease activity or the type of treatment they were on to obtain a representative sample of the RA population.

Control group (n = 30)

Healthy volunteers of the appropriate age, matched by sex, were recruited on the basis of hospital personnel, companions of patients, and respondents to recruitment advertisements posted in the community. The inclusion criteria were adults aged 1870 years and no individual history of TMJ disorders, symptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction, systemic inflammatory or autoimmune disorders, or severe facial trauma.

Exclusion criteria

In both groups, the exclusion criteria were (1) pregnancy or lactation (because of radiation effects on the imaging), (2) previous TMJ surgery or arthroscopy, (3) contraindications to imaging procedures, (4) other arthropathies that may confound assessment of the TMJ (osteoarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, and calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease), (5) history of significant facial trauma or developmental TMJ abnormalities, (6) inability to open the mouth adequately for standardized CBCT positioning or poor cooperation preventing reliable MSKUS examination.

Imaging protocols

CBCT

TMJ bilateral examination was done in Carestream CS 9300 CBCT scanner (Carestream Dental LLC, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) with the standard acquisition parameters: Tube voltage 90 kV, tube current 10 mA, exposure time 10.8 s, field of view 1010 cm, and isotropic voxel size 0.2 mm to achieve the high spatial resolution. To measure the dynamics of the condylar translation, the patients were placed in the scanner with a standardized head holder with the Frankfort horizontal plane being perpendicular to the floor, and images were taken with the mouth in closed and open positions.

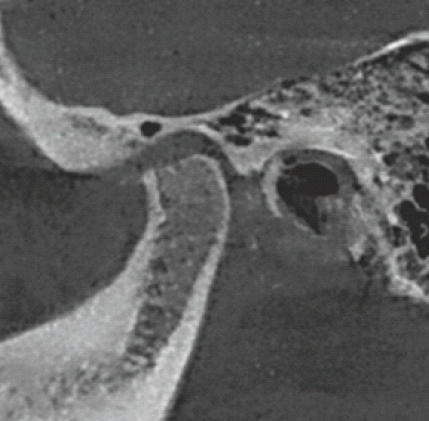

CBCT images were evaluated systematically the following changes of the bones: (1) cortical erosions, which are discontinuity or irregularity of cortical bone surface, a measure that was 0.1 mm or more, (2) osteophytes, which are bone outgrowths or excrescence of the articular surface, (3) subchondral cysts, which are well delimited areas of radiolucidity in the subchondral bone, (4) condylar flattening measured qualitatively, and (5) joint space width (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Temporomandibular joint cone-beam computed tomography section for the evaluation.

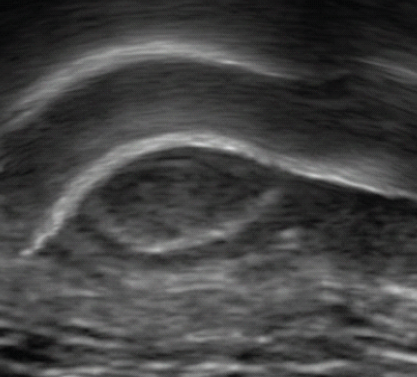

Bilateral TMJ ultrasound was carried out with an ultrasound system, Philips EPIQ 5 (Bothell, Washington, USA), high-frequency linear array transducer (12.5 MHz) that is optimized with regard to superficial musculoskeletal structures. Patients were positioned in the supine position with slight neck extension, and a standard set of scanning protocols was used. The transducer was placed in sagittal and coronal views on the region of the TMJ, and evaluations were done in closed-mouth and open-mouth positions to determine dynamic disc displacement (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Musculoskeletal ultrasound for the temporomandibular joint.

Systematic evaluations in MSKUS

(1) Joint effusion, determined by the presence of an anechoic or hypoechoic fluid collection in the joint space with a maximum dimension of more than 2 mm (2) Synovitis, identified by a hypoechoic synovial hypertrophy with augmented vascularity as observed on power Doppler imaging (Doppler settings: pulse repetition frequency 750 Hz, Doppler gain set slightly lower than noise level), (3) disc displacement, determined by identifying the articular disc as a hypoechoic biconcave structure positioned anterior to the condylar head in the closed-mouth view and failing to resume its normal interposed position during mouth opening.

Analysis and interpretation of images

The two musculoskeletal radiologists (R.S. and M.K., more than 5 years of special experience in TMJ imaging) reviewed all the CBCT and MSKUS images and were not informed about the group assignment (RA vs. control), clinical data, parameters of disease activity, and the outcome of the other imaging modality. The use of anonymized identification codes were used to ensure total blinding of the presentation of images in random order. The presence or absence of each pathological feature was noted using standardized reporting forms devised particularly to handle the study by both observers. To measure the joint space width (quantitative measurements), the observer made a separate set of measurements 3 times, and the average was obtained. The interobserver consistency was also evaluated, and where disagreement was observed as to the existence of certain pathological features, a consensus reading was conducted with a review and discussion of the cases to arrive at a final decision.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted with the help of IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics version 28.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test and Q-Q plot inspections were used to test normalcy of continuous variables. Continuous variables that were normally distributed were stated as mean and standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were stated as frequencies and percentages. Independent samples t-tests were used to make between-group comparisons (RA patients vs. healthy controls) of continuous normally distributed variables (age and joint space width). Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, when the expected cell frequencies were below 5, was used to compare categorical variables (presence/absence of erosions, osteophytes, effusion, synovitis, etc.). Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) between the two radiologists was used to determine whether there was interobserver agreement between the radiologists when assessing both CBCT and MSKUS using categorical variables, and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) when assessing measurements in the form of continuous variables. On the same note, intermodality agreement between CBCT and MSKUS in depicting similar pathological characteristics (erosions and cortical irregularities) was evaluated with the Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The interpretation of kappa was based on Landis and Koch’s criterion, where 0.20 is slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 is fair, 0.41–0.60 is moderate, 0.61–0.80 is substantial, and 0.81–1.00 is almost perfect agreement. All analyses had a two-tailed P < 0.05 as a statistical significance threshold.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The final study cohort comprised 60 RA patients (45 females [75.0%] and 15 males [25.0%]) with a mean age of 48.5 ± 12.3 years (range: 22–68 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.2 ± 5.1 years (range: 0.6–24 years) from initial RA diagnosis. The control group consisted of 30 healthy volunteers (22 females [73.3%] and 8 males [26.7%]) with a mean age of 46.8 ± 11.5 years (range: 24–67 years). No statistically significant differences were observed between groups regarding age distribution (P = 0.52) or sex ratio (P = 0.87), confirming successful matching. Among the RA patients, 43 (71.7%) were receiving conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), primarily methotrexate, 28 (46.7%) were on biologic DMARDs, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or other biologic agents, and 38 (63.3%) were receiving low-dose corticosteroids. The mean disease activity score-28 (DAS-28-erythrocyte sedimentation rate) was 3.8 ± 1.4, indicating moderate overall disease activity in the cohort.

CBCT assessment of osseous changes

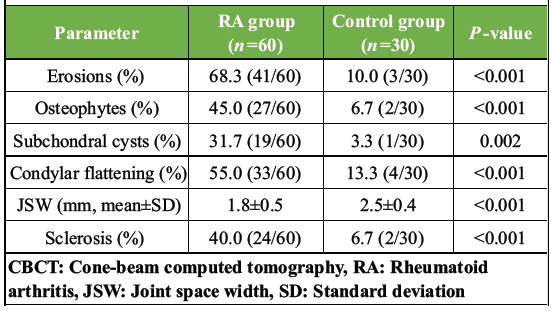

Table 1 presents the comprehensive comparison of osseous degenerative changes detected by CBCT between RA patients and healthy controls.

Table 1: Osseous changes on CBCT in RA patients versus controls

RA patients demonstrated significantly higher prevalence of all osseous degenerative features compared to healthy controls. Cortical erosions were identified in 68.3% of RA patients (41/60) versus only 10.0% of controls (3/30), representing a nearly seven-fold increase (P < 0.001). Osteophyte formation was present in 45.0% of RA patients compared to 6.7% of controls (P < 0.001), whereas subchondral cysts were detected in 31.7% versus 3.3% (P = 0.002). Condylar flattening, indicative of chronic degenerative remodeling, was observed in 55.0% of RA patients compared to 13.3% of controls (P < 0.001). Quantitative assessment of joint space width revealed significant narrowing in the RA group (mean joint space width: 1.8 ± 0.5 mm) compared to controls (2.5 ± 0.4 mm), representing an approximate 28% reduction in joint space (P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [CI] for difference: 0.48–0.92 mm). This finding reflects progressive cartilage loss and bone remodeling characteristic of chronic inflammatory arthropathy.

MSKUS assessment of soft tissue changes

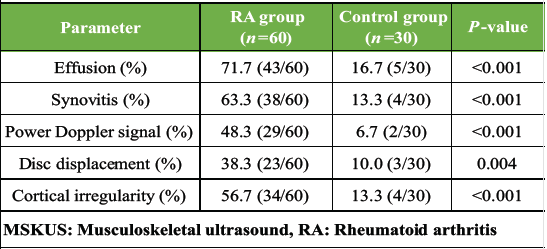

Table 2 summarizes the soft-tissue pathological features detected by MSKUS in both study groups.

Table 2: Soft tissue changes on MSKUS in RA patients versus controls

Joint effusion was the most prevalent soft tissue finding, detected in 71.7% of RA patients (43/60) compared to 16.7% of controls (5/30) (P < 0.001). Active synovitis, characterized by hypoechoic synovial hypertrophy, was present in 63.3% of RA patients versus 13.3% of controls (P < 0.001). Notably, a power Doppler signal indicating active hypervascularity and ongoing inflammation was demonstrated in 48.3% of RA patients compared to only 6.7% of controls (P < 0.001), highlighting the high prevalence of active inflammatory processes within the TMJ even in patients with apparently controlled systemic disease. Anterior disc displacement was identified in 38.3% of RA patients compared to 10.0% of controls (P = 0.004), suggesting that chronic inflammation and structural changes contribute to altered disc-condyle relationships. MSKUS also detected cortical irregularities in 56.7% of RA patients, demonstrating its capability to identify osseous surface changes, though with less detail than CBCT.

Intermodality agreement

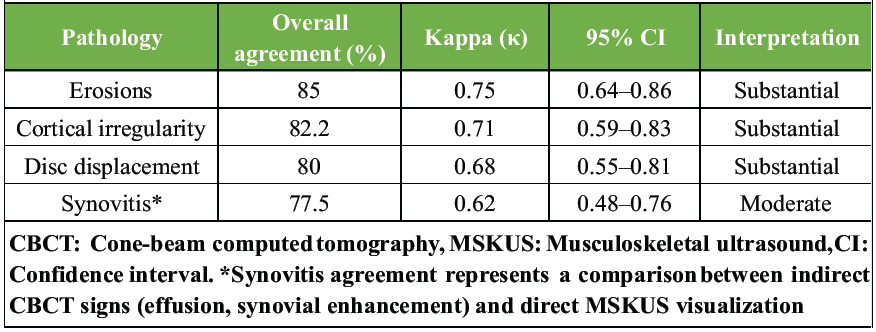

Table 3 presents the intermodality agreement analysis between CBCT and MSKUS for key pathological features that both modalities can potentially detect.

Table 3: Intermodality agreement (CBCT vs. MSKUS) for key pathologies

The analysis revealed substantial intermodality agreement for erosion detection (κ = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64–0.86), indicating that both modalities demonstrate concordant results in the majority of cases, though CBCT provided superior detail regarding erosion depth, extent, and precise anatomical location. Agreement for cortical irregularities was also substantial (κ = 0.71), whereas disc displacement assessment showed substantial agreement (κ = 0.68), with MSKUS offering the advantage of dynamic real-time assessment during mouth opening. Agreement for synovitis detection was moderate (κ = 0.62), reflecting the fundamental difference that MSKUS directly visualizes synovial tissue and associated vascularity, whereas CBCT can only suggest synovitis indirectly through secondary signs such as joint space widening or enhancement patterns when contrast is used.

Interobserver reliability

Interobserver agreement between the two independent radiologists was high for both imaging modalities. For CBCT assessments, Cohen’s kappa for categorical variables ranged from 0.78 to 0.86 (overall κ = 0.82), indicating almost perfect agreement. For MSKUS evaluations, kappa values ranged from 0.74 to 0.84 (overall κ = 0.79), representing substantial to almost perfect agreement. For joint space width measurements on CBCT, the ICC was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.87–0.94), demonstrating excellent interobserver reliability for quantitative assessments.

This prospective cross-sectional research offers strong evidence that both CBCT and MSKUS are very efficient imaging techniques to identify and describe TMJ degeneration in patients with RA, as each of the modalities can have its unique strengths regarding particular pathology. As our results show, CBCT is better at detailed examination of the changes in the structure of the bones, whereas MSKUS is better when it comes to analyzing the soft-tissue pathology and the active inflammatory processes. The fact that in our RA cohort, both atrophic and inflammatory alterations in the soft tissue and bone were common, with erosion in 68.3%, synovitis in 63.3%, and the presence of effusion in 71.7% of the patients, highlights the high frequency of TMJ involvement in the disease and the urgency of a systematic TMJ observation among them. Our study has found that 68.3% of the extent of erosion, which was identified, is consistent with the results of Larheim et al. [2], who indicated that TMJ involvement was noted in more than 70% of RA patients using superior imaging modalities, and our findings are in line with the findings of Hintze et al. [6], who reported similar erosion rates should RA be present using CBCT. The objective quantitative data of progressive joint destruction, cartilage breakdown, and bone remodeling, which are characteristic of chronic inflammatory arthropathy and have a direct effect on joint biomechanics and functioning, are evidence of the substantially smaller mean joint space width in RA patients (1.8 ± 0.5 mm) than in controls (2.5 ± 0.4 mm). The results of our MSKUS demonstrate that the joint effusion (71.7) and active synovitis (63.3) are the predominant soft-tissue pathological features in the process of degeneration of TMJ in RA, which is a strong argument in favor of MSKUS use as an effective instrument that can be used to identify active inflammation to change systemic or local treatment approaches. Those results are in line with the large body of evidence already established by Wakefield et al. [7] and other working groups of the outcome measures in rheumatology, who have already proved the high sensitivity and specificity of MSKUS in the detection of synovitis in peripheral joints in RA patients. The fact that a power Doppler signal was present in 48.3% of our RA patients indicates that continued inflammation and neovascularization of the TMJ synovium are still happening and may lead to continued joint destruction, even in patients who seem to have completely controlled systemic disease activity. Our moderate intermodality agreement of synovitis detection (0.62) is clinically significant and predictable since it indicates the inherent difference between what each modality images: MSKUS is a direct visualization of the hypertrophy of the synovial tissue and the hypervascularity of the synovial tissue in real-time with excellent soft-tissue contrast, and CBCT is a direct visualization of the skeletal structures and can only indirectly identify synovitis through some secondary effects of the disease, such as evidence of joint space format. This result supports the specific and complementary value of MSKUS in measuring soft-tissue inflammation, which cannot be sufficiently measured using CBCT. On the other hand, the high level of agreement on erosion detection (κ = 0.75) means that although MSKUS is capable of detecting cortical displacement and surface abnormalities, CBCT is the technique of choice for a detailed description of erosion severity, depth, and accurate distribution among different parts of the body [5]. One of the main strong points of this research is that it provides a comparative analysis of the two imaging modalities on the same well-characterized RA cohort, addressing the important gap that exists in the existing body of literature directly. A majority of the past research has been based on individual imaging modalities, hence restricting the overall knowledge of the TMJ pathology and avoiding the need to define how the modalities can be used together in clinical practice [10]. The results of our study are strong arguments in favor of a dual-imaging solution to specific clinical cases: MSKUS could be an outstanding first line screening tool and monitoring modality to identify active inflammation and soft-tissue changes (especially in the facilities where serial follow-up evaluations are required), but CBCT should be used to provide detailed evaluation of the bone (especially in symptomatic patients), when structural complications are suspected, or when therapeutic choices require an accurate interpretation of the anatomy. The given strategic imaging approach is consistent with the recent EULAR guidelines, where such an approach is recommended to be used in the RA diagnostic process only partially and primarily due to its high diagnostic quality and the need to balance the effects of radiation exposure with cost-effectiveness and accessibility [8]. Radiation-free root of MSKUS ensures its use is more appealing to serial monitoring of the disease activity and treatment response, whereas the high level of detail in the bones in CBCT warrants its usage when the definite evaluation of the structure is clinically warranted. In addition to the direct diagnostic implications, our results have significant clinical implications for the management of RA. The large incidence of TMJ degeneration, both in active inflammation and structural degeneration, even in patients with modern treatment programs, indicates that contemporary therapeutic interventions are not sufficient to treat the involvement of TMJ. This finding brings up significant concerns over whether TMJ-specific testing ought to be added to regular RA monitoring regimes, and whether or not TMJ involvement ought to be the basis upon which treatment escalation decisions are made. Moreover, active inflammation (which was proved by power Doppler signal in close to half of our patients) may open up some prospects of specific interventions, such as corticosteroid injections within the joint or local treatment based on the results of the image.

Limitations of the study and future directions

There are a number of limitations that should be considered when discussing our findings. To begin with, the cross-sectional design does not allow the study to examine longitudinal disease progression, the relationship of imaging results with clinical manifestations, and the outcome of the imaging results in response to therapeutic interventions. Serial imaging at pre-established intervals would be useful in understanding the natural history of TMJ degeneration in RA and potentially allow the determination of prognostic imaging biomarkers. Second, although our sample size was sufficiently powered to make the key comparisons, subgroup analyses to investigate the association between imaging outcomes and certain clinical outcomes (disease duration, DASs, specific treatment regimens, and autoantibody status) would be better served by larger cohorts. We also have not systematically compared imaging results with more comprehensive clinical TMJ evaluations of pain scores, maximum mouth opening, or TMJ-specific quality of life scales, which would reinforce the clinical applicability of imaging results. Third, MSKUS is operator-dependent, and the technique differences can have implications on cross-center and cross-operator reproducibility. Nevertheless, the fact that we have a high interobserver agreement (K = 0.79) between experienced musculoskeletal radiologists with standardized protocols negatively impacts this issue and shows that one can attain reliable results with proper training and standardization of techniques. Further studies are needed to create and test standardized MSKUS protocols in particularly tailored to TMJ measurement in RA, possibly with semi-quantitative or quantitative scoring, similar to those already developed with peripheral joints. Fourth, we did not involve magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is the gold standard of soft-tissue evaluation and may give complementary data on cartilage condition, bone marrow edema, and disc appearance. Further comparative examinations with both MRI and CBCT, and MSKUS in the future would offer more extensive insights into the comparative diagnostic performance of all accessible modalities. Finally, we only performed a study at one tertiary care center, which is not necessarily representative of another healthcare facility, a population with varying RA phenotypes, or environments with limited resources. The external validity of these findings would be enhanced by multicenter research that would utilize a wide range of population and healthcare settings.

This thorough research presents strong evidence that RA patients have significant TMJ degeneration involving the presence of both the osseous and soft-tissue structures and high rates of pathological changes as opposed to healthy controls in all the measures of interest. CBCT has proved to be superior in detailed evaluation of the changes in the osseous structures, such as erosions, osteophytes, subchondral cysts, and quantitative evaluation of loss of the joint space, whereas MSKUS is more effective in detection and characterization of the soft-tissue pathology, such as synovial effusion, active synovitis with the associated neovascularization, and dynamic movement of the disc. The large intermodality concordance of the main pathological features, as well as the specific merits of the corresponding modalities, highly prove the clinical expediency of the joint use of both imaging methods in a complementary manner. We suggest evidence-based, customized imaging, MSKUS as the first line of screening, monitoring of inflammatory processes, and serial follow-up (utilizing its radiation-free nature, real-time capabilities, and sensitivity of soft tissues) and CBCT as the comprehensive evaluation of the skeletal system in symptomatic patients, when there is a suspicion of structural complications, or to determine the anatomical specifics to make a definitive therapeutic choice. These results support the idea of introducing the use of modern imaging, in particular, CBCT and MSKUS, in everyday RA management guidelines and allow timely identification of TMJ involvement, provide a more focused disease observation, define an individual approach to treatment, and eventually enhance TMJ-specific and overall patient results. Systematic TMJ surveillance by means of these complementary imaging modalities can change the clinical management by detecting subclinical disease, active inflammation that is open to intervention, and preventing the further advancement to permanent structural deformity and functional disability.

Temporomandibular joint involvement in RA is far more common than clinically appreciated, and many patients develop significant synovitis and structural degeneration even in the absence of marked symptoms. This study demonstrates that combining CBCT and MSKUS provides the most accurate and comprehensive assessment of TMJ pathology in RA by capturing both subtle early inflammatory changes and advanced osseous destruction that may otherwise go undetected. Integrating this dual-modality imaging approach into routine evaluation can facilitate early diagnosis, guide timely therapeutic intervention, prevent irreversible joint deformity, and significantly improve functional outcomes and overall quality of life in RA patients.

References

- 1. Smolen JS, Landewé RB, Bijlsma JW, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:685-99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Larheim TA, Abrahamsson AK, Kristensen M, Arvidsson LZ. Temporomandibular joint diagnostics using CBCT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2015;44:20140235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Alstergren P, Larsson PT, Kopp S. Successful treatment of arthralgia of the temporomandibular joint in rheumatoid arthritis by intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate. J Oral Rehabil 2018;45:321-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Ahmad M, Hollender L, Anderson Q, Kartha K, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD): Development of image analysis criteria and examiner reliability for image analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;107:844-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Hintze H, Wiese M, Wenzel A. Cone beam CT and conventional tomography for the detection of morphological temporomandibular joint changes. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007;36:192-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Koyama J, Nishiyama A, Matsuda T, et al. Comparison of imaging modalities for the detection of erosions in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016;121:38-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Wakefield RJ, Balint PV, Szkudlarek M, Filippucci E, Backhaus M, D’Agostino MA, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2485-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Colebatch AN, Edwards CJ, Østergaard M, Van Der Heijde D, Balint PV, D’Agostino MA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging of the joints in the clinical management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:804-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Elbesouty L, Flanagan A, Foster H, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound of the temporomandibular joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Reliability and discriminatory ability. J Rheumatol 2017;44:189-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Dijkstra PU, Kropmans TJ, Stegenga B, De Bont LG. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis and generalized joint hypermobility. Cranio 2002;20:177-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]