Chronic juvenile massive OCD may achieve fusion with fixation, even when bone fragments consist only of cartilage.

Dr. Akira Maeyama, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan. E-mail: akira.maeyama0713@joy.ocn.ne.jp

Introduction: Chronic juvenile massive osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) presents significant therapeutic challenges due to the lack of established treatments. We herein report a case of chronic juvenile massive OCD treated with poly-L-lactic acid pin fixation.

Case Report: A 13-year-old boy presented to another hospital with right knee pain after playing football. Initially, no significant abnormalities were noted, and he was placed under observation. However, the pain later worsened, and he was referred to our hospital with a diagnosis of OCD. An X-ray revealed a defect posterior to the lateral femoral condyle and a loose body in the suprapatellar bursa. Magnetic resonance imaging indicated the presence of a lateral discoid meniscus. Three months after the onset of symptoms, osteochondral fragment fixation and saucerization of the lateral meniscus were performed. One year postoperatively, the patient showed a good outcome with no recurrence of symptoms.

Conclusion: Chronic juvenile massive OCD may achieve fusion with fixation, even when bone fragments consist only of cartilage.

Keywords: Juvenile, knee, osteochondritis dissecans, poly-L-lactic acid pin.

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the knee is one of the most common causes of knee pain and dysfunction in children and adolescents. It is an acquired, reversible, idiopathic subperiosteal lesion [1]. This condition is believed to be caused by repeated microtrauma due to overuse [2]. Approximately 19% of OCD cases of the lateral femoral condyle coexist with a discoid meniscus [3]. The presence of a discoid meniscus can cause abnormal contact forces on the lateral femoral condyle, leading to OCD, even without a meniscal tear [4]. There are few reports on the treatment of massive OCD with a discoid meniscus, and the optimal treatment approach remains undetermined [5]. Treating osteochondral defects due to massive OCD can be challenging because a single surgical technique may not be sufficient to address the defect [6]. Surgical options for OCD include bone fragment extraction, drilling, osteochondral fragment fixation, and autologous chondrocyte implantation. The indication for surgery in juvenile OCD should consider the patient’s age, the lesion’s location, the extent of injury, and disease progression [7]. Recent studies have reported favorable outcomes with internal fixation using bioabsorbable implants for OCD [2,5,6,8]. We herein present a case of chronic juvenile massive OCD, 3 months post-injury, treated with internal fixation using poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) pins.

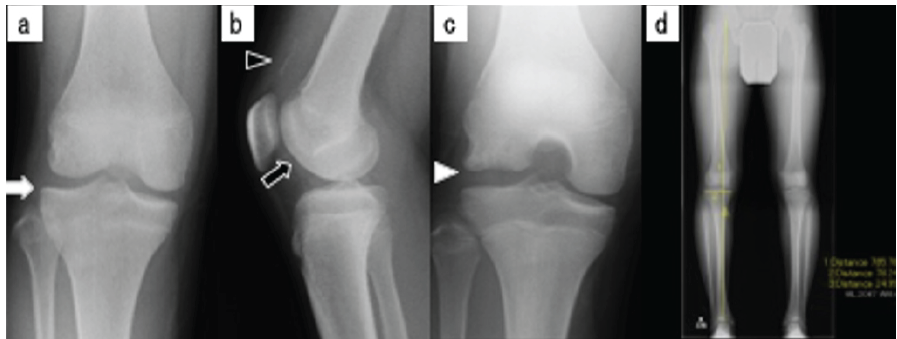

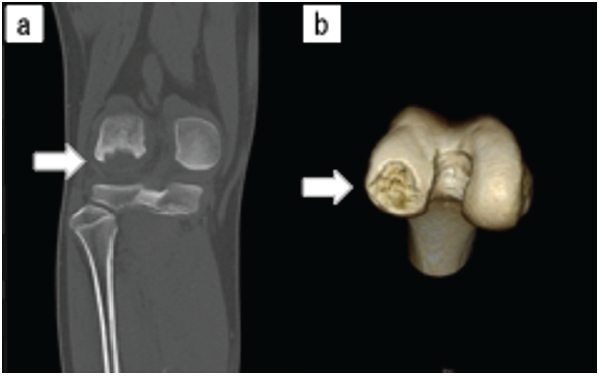

A 13-year-old boy experienced right knee pain while playing football 3 months before his first visit. He was initially diagnosed with a meniscus injury by a local doctor, and he underwent conservative treatment and resumed exercise after 1 month because the pain had subsided. However, the pain recurred, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee joint revealed extensive OCD. He was then referred to our hospital. Physical examination showed a right knee joint range of motion of 0° extension and 140° flexion, with tenderness along the lateral joint line and a positive McMurray test. No ligamentous instability was noted. The Lysholm score was 29 points. X-ray examination at the initial examination revealed flattening of the lateral tibial condyle in the frontal view (Fig. 1a), notch less sign in the lateral view, a loose body in the lateral suprapatellar bursa (Brückl classification stage IV) (Fig. 1b), and a defect posterior to the lateral femoral condyle on the intercondylar fossa view (Fig. 1c). A standing full-length X-ray of the lower limb showed a femorotibial angle of 178° and mechanical axis deviation of 32% (Fig. 1d). Computed tomography indicated a free body measuring 24 mm length and 26 mm width, consistent with a bony defect posterior of the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: (a) Simple X-ray image showing a flattened lateral tibial condyle (white arrow) in the frontal view. (b) notch less sign (black arrow) in the lateral view. (c) A free body (white arrowhead) in the lateral supracondylar sac and a defect posterior to the lateral femoral condyle (black arrowhead) in the intercondylar fossa radiograph. (d) A full-length standing X-ray of the lower limb showing a femorotibial angle of 178° and mechanical axis deviation of 32%.

Figure 2: (a) Computed tomography image (coronal section) showing a bone defect posterior to the lateral femoral condyle (white arrow). (b) Three-dimensional computed tomography image showing the size of the bone defect posterior to the lateral femoral condyle, measuring 24 mm in length and 26 mm in width.

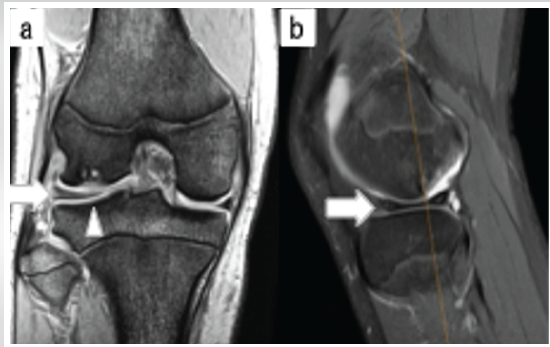

MRI revealed a lateral discoid meniscus (Mink classification grade 2), with the meniscus absent at the site of OCD. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments were intact (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: (a) Magnetic resonance image (T2* coronal section) showing a lateral discoid meniscus (Mink classification grade 2) (white arrowheads). (b) Magnetic resonance image (fat-suppressed T2-weighted sagittal section) showing the absence of the meniscus at the site of osteochondritis dissecans (white arrowhead).

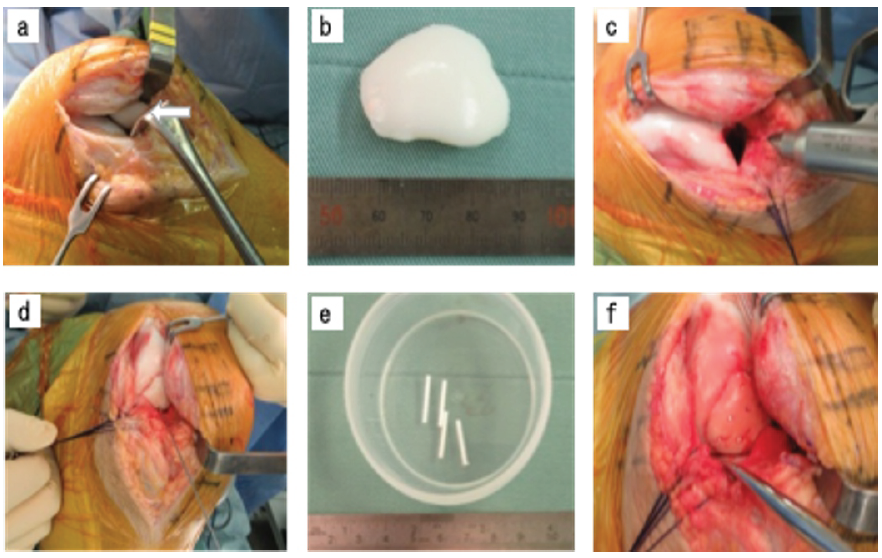

Considering the patient’s refractoriness to conservative treatment, age, fragment size, and injury site, we planned either fixation of the free osteochondral fragments or autologous chondrocyte implantation. Arthroscopic findings showed an incomplete lateral discoid meniscus, which was treated by saucerization. The lateral parapatellar approach was used to remove the free osteochondral fragments (Fig. 4a). These fragments consisted of articular cartilage and subchondral bone with smooth margins and no cracks (Fig. 4b). After dissecting the subchondral bone (Fig. 4c), the osteochondral fragment was well-adapted (Fig. 4d), and fixation was performed using PLLA pins (Fig. 4e and f).

Figure 4: (a) The lateral parapatellar approach was used to expand and remove the free osteochondral fragment (white arrow). (b) The bone fragment consisted of articular cartilage and subchondral bone with smooth margins and no cracks. (c) After dissecting the matrix. (d) The osteochondral fragment was well adapted. (e) Internal fixation was performed with a poly-L-lactic acid pin. (f) Post-fixation image.

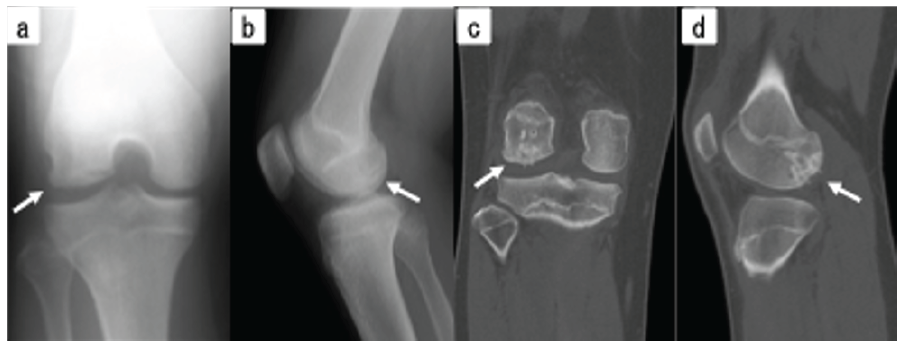

The patient was immobilized in extension for 2 weeks postoperatively and was non-weight-bearing for 6 weeks. Five months postoperatively, X-rays and computed tomography scans confirmed bony fusion (Fig. 5), and the Lysholm score improved from 29 preoperatively to 95 postoperatively. The patient returned to sports 6 months after surgery, with no symptom recurrence after 1 year.

Figure 5: (a) Simple X-ray (frontal view). (b) Simple X-ray (lateral view). (c) Simple computed tomography (coronal section). (d) Simple computed tomography (sagittal section), all showing bone fusion 5 months after surgery (white arrow).

Surgical treatment of juvenile OCD is advised for patients with loose bone fragments and unstable lesions or patients with stable lesions unresponsive to conservative treatment, particularly those nearing epiphyseal closure [1,8,9]. Surgical treatment is typically recommended for stage IV or V lesions according to the Brückl classification and stage III or IV lesions based on the arthroscopic Guhl classification [10]. However, the criteria for surgical intervention, including lesion size, location (weight-bearing area or not), and degree of bone fragment degeneration, remain unclear. Massive OCD in the weight-bearing area may predispose to future knee osteoarthritis and warrants surgical intervention [6]. Adachi et al. [10] performed internal fixation in 10 knees with unstable OCD lesions and evaluated the osteochondral repair process histologically. They reported significant improvements in the histological scores, even in patients with a relatively long history (more than a few months). Touten et al. [11] demonstrated in a rabbit model that osteochondral fragments isolated for less than 12 weeks showed favorable histological findings with abundant extracellular matrix, highlighting the clinical importance of early fixation and anatomical cartilage repair. Bone fragments avulsed months earlier retain viable articular cartilage on their surface and continue to grow through synovial fluid, necessitating proper alignment with the lesion site during fixation [12]. Thomson [13] found that even cartilage fragments without bone attachment contain a calcified layer that supports viable implantation if the fibrous tissue of the matrix is sufficiently curetted and the subchondral bone is freshened. Internal fixation materials include bioabsorbable, metal, and autogenous bone materials, such as bone pegs. Bioabsorbable screws are safe and effective for unstable OCD lesions, providing stability with minimal reaction to degradation products [14]. The advantages of bioabsorbable screws include the lack of need for removal, which is often required for metal implants, and compatibility with MRI. However, complications such as synovitis, loss of fixation, and aseptic abscesses have been reported [7,14]. Typically, two to four implants are needed, and they must be inserted at an angle to avoid damaging growth plates [12]. Kubota et al. [15] reported medium- to long-term outcomes of fixation for OCD, highlighting that the use of bioabsorbable pins is an effective technique with favorable long-term results regardless of skeletal maturity and lesion size or severity. The main advantages of bioabsorbable implants are slower load transfer to the bone during the implant resorption process and the elimination of the need for subsequent implant removal. However, a disadvantage is the risk of non-union due to the reduced rigidity of the fixation [16]. For large cartilage defects, osteochondral fragment fixation with internal fixation material is preferred if the bone fragments are compatible; otherwise, autologous osteochondral column grafting should be considered [7]. Camathias et al. [5] reported a case of massive OCD with a discoid meniscus treated with saucerization and osteochondral fragment fixation using bioabsorbable screws, resulting in a favorable outcome. Previous reports did not describe PLLA pin fixation alone for chronic massive OCD of the lateral femoral condyle load area of >500 mm2 in size. In this case, although the free osteochondral fragment was several months old and consisted only of cartilage, it was well-adapted, and mosaic plasty was not performed. The patient underwent osteochondral fragment fixation using PLLA pins, achieving a favorable outcome in a short period. Nevertheless, this report describes the clinical course of a single adolescent patient, and the findings should therefore be interpreted with caution. The follow-up period was limited to 1 year, and longer-term evaluation is required to assess the durability of fixation, the risk of recurrence, and the potential development of degenerative changes in the knee joint. In addition, this study did not include a comparative or control group treated with alternative surgical options such as osteochondral autograft transplantation, drilling, or autologous chondrocyte implantation; thus, the relative effectiveness of PLLA pin fixation cannot be determined. Furthermore, although radiological union and favorable clinical improvement were achieved, no histological evaluation or second-look arthroscopy was performed to objectively assess the quality of cartilage and subchondral bone healing. Finally, osteochondral fragment fixation was performed in combination with saucerization of a discoid lateral meniscus. Therefore, the independent contribution of PLLA pin fixation to the favorable clinical outcome cannot be clearly distinguished from the biomechanical improvement achieved by meniscal correction.

This case suggests that in patients with massive OCD approximately 3 months post-injury, internal fixation may lead to bony fusion, even if the loose bone fragments consist solely of cartilage.

Chronic Juvenile Massive OCD lesions may achieve sufficient bone healing with fixation. This can be an important consideration when determining treatment strategies or surgical indications.

References

- 1. Flynn JM, Kocher MS, Ganley TJ. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:434-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Galagali A, Rao M. Osteochondritis dessicans- primary fixation using bioabsorbable implants. J Orthop Case Rep 2012;2:3-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kramer DE, Micheli LJ. Meniscal tears and discoid meniscus in children: Diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17:698-707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Yaniv M, Blumberg N. The discoid meniscus. J Child Orthop 2007;1:89-96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Camathias C, Rutz E, Gaston MS. Massive osteochondritis of the lateral femoral condyle associated with discoid meniscus: Management with meniscoplasty, rim stabilization and bioabsorbable screw fixation. J Pediatr Orthop B 2012;21:421-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Lee BI, Kim BM. Concomitant osteochondral autograft transplantation and fixation of osteochondral fragment for treatment of a massive osteochondritis dissecans: A report of 8-year follow-up results. Knee Surg Relat Res 2015;27:263-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Winthrop Z, Pinkowsky G, Hennrikus W. Surgical treatment for osteochondritis dessicans of the knee. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2015;8:467-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Quigley R, Allahabadi S, Yazdi AA, Frazier LP, McMorrow KJ, Meeker ZD, et al. Bioabsorbable screw fixation provides good results with low failure rates at mid-term follow-up of stable osteochondritis dissecans lesions that do not improve with initial conservative treatment. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2024;6:100863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Hefti F, Beguiristain J, Krauspe R, Möller-Madsen B, Riccio V, Tschauner C, et al. Osteochondritis dissecans: A multicenter study of the European pediatric orthopedic society. J Pediatr Orthop B 1999;8:231-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Adachi N, Motoyama M, Deie M, Ishikawa M, Arihiro K, Ochi M. Histological evaluation of internally-fixed osteochondral lesions of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:823-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Touten Y, Adachi N, Deie M, Tanaka N, Ochi M. Histologic evaluation of osteochondral loose bodies and repaired tissues after fixation. Arthroscopy 2007;23:188-96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Jones MH, Williams AM. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: A practical guide for surgeons. Bone Joint J 2016;98-B:723-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Thomson NL. Osteochondritis dissecans and osteochondral fragments managed by Herbert compression screw fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;224:71-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Tabaddor RR, Banffy MB, Andersen JS, McFeely E, Ogunwole O, Micheli LJ, et al. Fixation of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee using poly 96L/4D-lactide copolymer bioabsorbable implants. J Pediatr Orthop 2010;30:14-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kubota M, Ishijima M, Ikeda H, Takazawa Y, Saita Y, Kaneko H, et al. Mid and long term outcomes after fixation of osteochondritis dissecans. J Orthop 2018;15:536-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Wiktor Ł, Tomaszewski R. Evaluation of osteochondritis dissecans treatment with bioabsorbable implants in children and adolescents. J Clin Med 2022;11:5395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]