Medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy effectively improves pain and function in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis by restoring lower limb mechanical alignment when performed with stable fixation and appropriate patient selection.

Dr. Satyam S Jha, Department of Orthopaedics, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: satyam.jha.77@gmail.com

Introduction: Medial compartment knee osteoarthritis (OA) with varus alignment is a common degenerative condition leading to pain, functional limitation, and reduced quality of life. High tibial osteotomy (HTO) by the open wedge technique is a joint-preserving option aimed at realigning the mechanical axis.

Objectives: This study aims to evaluate the functional and radiological outcomes of medial open wedge HTO in patients with medial knee OA and varus deformity.

Material and Methods: We conducted a prospective study at Hamidia Hospital, Bhopal, for 2 years with 6 months follow-up of each patient. Twenty-five patients of symptomatic medial compartment OA diagnosed by standing X-rays and Scannogram, underwent medial open wedge HTO using TomoFix plate. Outcome was assessed using standing X-rays, visual analog scale (VAS), and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities OA Index (WOMAC) scores. All patients were classified by the Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) system. We excluded patients with secondary knee OA.

Results: In our patients, 72% of patients were elderly women, and the mean age was 62.76 years. Most had KL Grade 3 OA (72%), with the left knee more commonly affected (62.5%). Although we have not found a significant improvement at 4 weeks, theVAS score improved from 6 weeks onward (P < 0.001), with mean VAS 4.48 at 12 weeks and 3.44 at 18 weeks, respectively. WOMAC score also improved at 6 weeks (mean change: 2.32, P = 0.022) and at 12, 18, and 24 weeks (mean changes: 11.64, 21.92, and 35.56, respectively; all P < 0.001). Radiologically, a mean correction of 9.72° (±0.89) was achieved, with successful restoration of mechanical alignment for a mean varus of 2.40 ± 0.65°.

Conclusion: Medial open wedge HTO is an effective treatment modality for selected patients with medial compartment OA and varus alignment. It provides significant pain relief and functional improvement. Proper patient selection, pre-operative planning, surgical technique, and rehabilitation are critical for optimal outcomes.

Keywords: High tibial osteotomy, medial compartment osteoarthritis, varus knee, open wedge osteotomy, mechanical axis correction.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disorder characterized by progressive articular cartilage degeneration, subchondral bone changes, and altered joint biomechanics, leading to pain, deformity, and functional limitation. Knee OA is particularly prevalent in Asian populations, where varus alignment and predominant medial compartment involvement are common, largely due to cultural practices such as frequent squatting, kneeling, and floor sitting, along with increasing obesity and sedentary lifestyles. Patients with knee OA often experience chronic pain, reduced mobility, dependence on assistive devices, and significant socioeconomic burden due to loss of productivity and increased healthcare utilization. The Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) classification system is widely used to guide management, with early stages managed conservatively, and avoiding further damage requires surgical intervention to restore alignment and function. Although several surgical options exist for the management of medial compartment knee OA, high tibial osteotomy (HTO), first popularised by Coventry, remains a well-established joint-preserving procedure in relatively young and active patients with varus deformity. Medial open-wedge HTO (MOWHTO) has gained popularity due to advantages such as precise correction, preservation of bone stock, and less risk of injury to the common peroneal nerve. While multiple studies and meta-analyses have reported favorable outcomes following HTO, most available literature includes heterogeneous patient populations, varied fixation methods, and data predominantly from non-Indian population. There remains a relative paucity of region-specific data evaluating functional and radiological outcomes of MOWHTO using standardized fixation systems in patients with isolated medial compartment OA and varus alignment. [1] The present study was undertaken to evaluate the clinical and radiological outcomes of MOWHTO using TomoFix plate fixation in patients with primary knee OA involving the medial compartment and varus deformity. By assessing post-operative pain relief, functional improvement, and mechanical axis correction through radiographic analysis, this study aims to provide context-specific evidence on the effectiveness and safety of this procedure in a rural central Indian population. The findings are intended to contribute to existing literature by offering data from a carefully selected, procedure-specific group of patients with close follow-up for outcome analysis.

A prospective observational study was designed and conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics at Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, and Hamidia Hospital, over an 18-month interval from May 1, 2023, to October 31, 2024. Institutional ethical approval was obtained (IEC no. 18863, Date: 09/05/2023). Before enrollment, each participant received comprehensive information regarding study aims, surgical procedures, potential risks, benefits, and follow-up requirements, and provided written informed consent.

Study population and enrollment

Candidates were recruited consecutively from outpatient and inpatient services, with screening based on clinical and radiographic criteria. There was no group for comparison in this study. Eligible subjects were adults aged over 35 years presenting with symptomatic primary medial compartment knee OA, with or without varus alignment, who were deemed suitable for joint-preserving osteotomy. Exclusion criteria encompassed post-traumatic OA, inflammatory arthropathies, and secondary OA, to maintain a homogeneous cohort focused on primary degenerative OA. A prevalence of 30%, as reported by Yadav et al., was used with a 95% confidence level and an allowable error of 10%, yielding an estimated minimum sample size [2]. However, as only a subset of patients with knee OA present with isolated medial compartment involvement and varus deformity and are suitable for joint-preserving surgery, all patients meeting the eligibility criteria visiting the outpatient department, were informed and enrolled for MOWHTO. A total of 25 patients were enrolled for outcome analysis.

Radiographic evaluation and deformity analysis

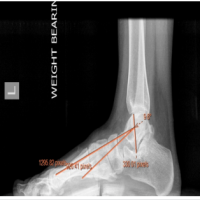

Weight-bearing knee radiographs (anteroposterior and lateral) were obtained to confirm medial compartment OA and grade severity using the KL classification [3]. Full-length, weight-bearing hip-knee-ankle scanograms were acquired with strict attention to limb positioning: Central patella, appropriate visibility of the lesser trochanter, and fibular head overlap ensured accurate axis measurements. We determined the mechanical tibiofemoral angle and joint line convergence angle (JLCA), crucial for planning correction.

Pre-operative planning: Miniaci method

Pre-operative planning utilized the Miniaci technique for the determination of wedge opening in medial open-wedge osteotomy [4]. On weight-bearing scanograms, the planned weight-bearing line (first line) was drawn from the hip center through the desired point on the tibial plateau to the anticipated ankle center. The hinge point was identified on the lateral proximal tibia adjacent to the fibular head. The angle between the line from the ankle center to the hinge point and the line from the hinge point to the anticipated new ankle center represented the required correction angle. When a self-correction component of JLCA was expected, this angle was subtracted from the total planned correction. The resultant angle was converted into a gap size at the osteotomy site using trigonometric reference charts.

Surgical technique

Under spinal anesthesia, patients were positioned supine on the operating table with the affected limb prepared for a sterile field. A thigh tourniquet was applied, and exsanguination was done. An 8 cm longitudinal incision was made along the anteromedial proximal tibia. The pes anserinus tendons were retracted posteriorly. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a Kirschner wire was inserted approximately 3–4 cm below the medial tibial plateau to delineate the osteotomy plane. A biplanar osteotomy was initiated using an oscillating saw, carefully stopping approximately 15 mm short of the lateral cortex to preserve a hinge. A 2 mm Kirschner wire is inserted along the lateral cortex of the proximal tibia to provide additional protection against an iatrogenic hinge fracture [5]. Gradual opening of the medial wedge using a lamina spreader to the predetermined angle; alignment was confirmed with a long alignment rod and fluoroscopy. Care was taken to maintain posterior tibial slope during gap opening, as unintended increases in slope following medial open-wedge HTO have been associated with altered knee biomechanics and instability. [6,7] Fixation was achieved using a TomoFix plate, positioned over the osteotomy, followed by insertion of locking screws parallel to the tibial plateau surface [8]. Layered closure proceeded after irrigation, hemostasis, and drain placement, with periosteum and subcutaneous layers followed by skin closure.

Post-operative management and rehabilitation

Rehabilitation followed a phased, time- and criterion-based protocol. During the early phase (0–6 weeks), protected weight-bearing was maintained with gradual progression from non- to partial weight-bearing based on radiographic evidence of early union. Passive and active-assisted range-of-motion exercises were initiated early, aiming for 90° knee flexion by 4 weeks, along with isometric quadriceps strengthening. In the intermediate phase (6–12 weeks), weight-bearing progressed to full, with emphasis on range-of-motion, closed-chain strengthening, and proprioceptive training. The late phase (beyond 3 months) focused on functional strengthening and gradual return to low-impact activities, with higher-impact activities permitted only after confirmed consolidation.

Outcome measures

Primary clinical outcomes included pain relief and functional improvement measured by Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities OA Index (WOMAC) scores at predefined intervals (e.g., 4, 6, 12, 18, and 24 weeks). Radiographic outcomes focused on mechanical axis correction quantified through post-operative radiographs. Complications were recorded systematically, encompassing intraoperative events (e.g., hinge fractures, neurovascular injury), early post-operative issues (e.g., infection, wound healing problems), and delayed complications (e.g., nonunion, loss of correction, hardware irritation or failure).

Data collection and management

Data collection employed structured proformas for consistency, capturing demographic data, clinical findings, radiographic measurements, intraoperative details, rehabilitation milestones, outcome scores, and complications at each follow-up visit. A master spreadsheet in MS Excel collated all variables, enabling organized data management. Regular data audits ensured completeness and accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using EPI Info 7.0. Continuous variables (e.g., VAS scores, mechanical axis deviation) were expressed as mean±standard deviation, while categorical variables (e.g., complication incidence) were reported as frequencies and percentages. Pre-operative versus post-operative comparisons utilized paired tests (e.g., paired t-test or nonparametric equivalent) with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

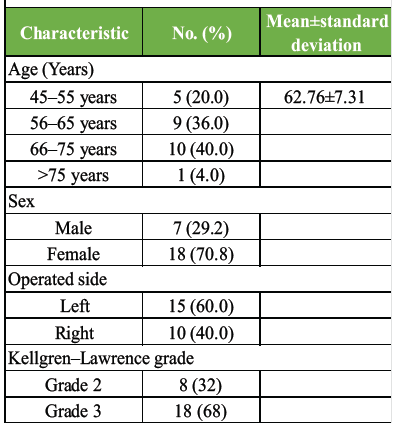

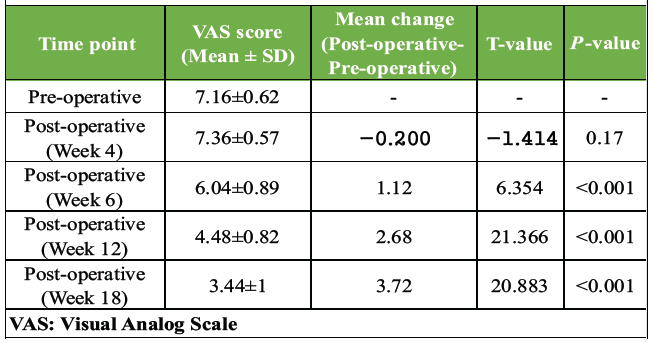

A total of 25 patients underwent MOWHTO during the study period. The mean age of the cohort was 62.76 ± 7.31 years, with the majority being female (n = 18; 72.0%). Left-sided procedures predominated (n = 15; 62.5%). Preoperatively, all patients presented with symptomatic primary medial compartment knee OA. According to the KL grading system, 18 patients (72.0%) had Grade 3 OA, indicating moderate-to-severe radiographic changes (Table 1). The mean pre-operative correcting angle, determined via weight-bearing scanograms and the Miniaci method, was 12.08 ± 1.06°. Baseline pain and functional impairment were substantial: The mean pre-operative VAS score was 7.16 ± 0.62, and the mean pre-operative WOMAC score was 56.56 ± 4.85, signifying marked functional limitation.

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics

Pain intensity was assessed by VAS at baseline and at specified post-operative intervals (4, 6, 12, and 18 weeks). At 4 weeks postoperatively, the mean VAS was 7.36 ± 0.57, with a mean change of –0.20 from baseline (P = 0.170). By 6 weeks postoperatively, the mean VAS score had decreased to 6.04 ± 0.89, representing a mean improvement of 1.12 points compared to baseline (P < 0.001) [9,10]. Subsequent assessments at 12 and 18 weeks showed continued and progressive pain relief. At 12 weeks, the mean VAS was 4.48 ± 0.82 (mean change 2.68; P < 0.001), and by 18 weeks, the mean VAS further decreased to 3.44 ± 1.00 (mean change 3.72; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2: Changes in pain intensity (VAS) from pre- to post-operative

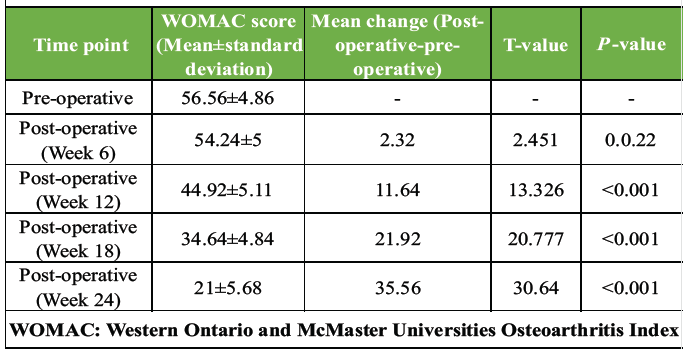

Functional outcome was assessed using WOMAC scores preoperatively and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 weeks postoperatively. The mean baseline WOMAC score was 56.56 ± 4.86. A modest but statistically significant improvement was noted at 6 weeks (54.24 ± 5.00; mean change 2.32; P = 0.022). More substantial improvement occurred by 12 weeks (44.92 ± 5.11; mean change 11.64; P < 0.001), with continued functional gains at 18 weeks (34.64 ± 4.84; mean change 21.92; P < 0.001) and 24 weeks (21.00 ± 5.68; mean change 35.56; P < 0.001). These findings demonstrate progressive and clinically meaningful functional recovery following medial open wedge HTO, particularly from 12 weeks onward (Table 3).

Table 3: Changes in functional status (WOMAC) from pre- to post-operative

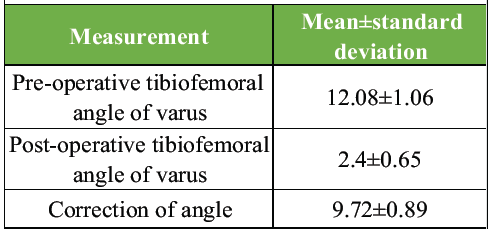

Radiographic assessment demonstrated significant correction of varus alignment. The mean pre-operative deformity was 12.08 ± 1.06°, which was corrected postoperatively with a mean value of 2.40 ± 0.65°. This achieved effective offloading of the medial compartment. Consistent alignment correction across follow-up indicated stable fixation and reliable surgical technique, correlating with observed clinical improvements in pain and function (Table 4).

Table 4: Radiographic outcomes following high tibial osteotomy

Post-operative complications were minimal in this series. One patient developed a superficial surgical site infection, which was successfully managed with regular sterile dressings and a short course of oral antibiotics, with no requirement for surgical intervention. Two patients experienced minor post-operative wound dehiscence, both of which healed uneventfully with conservative management using sterile dressings. No cases of lateral cortical hinge fracture, implant failure, loss of correction, deep vein thrombosis, or neurovascular complications were observed during the follow-up period.

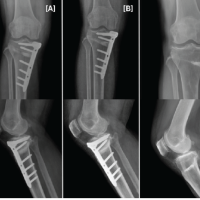

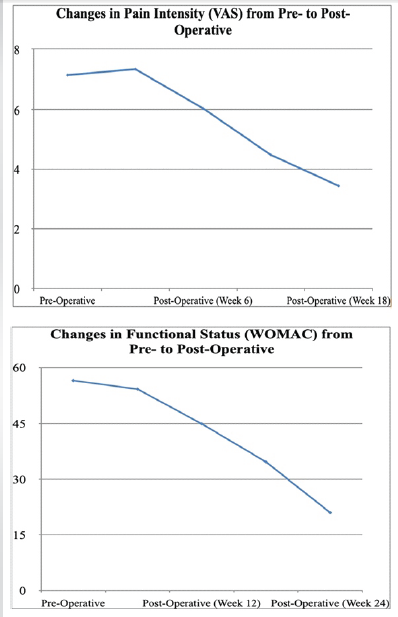

In our current research, we found that in the cohort of 25 patients, the mean age was 62.8 ± 7.3 years, with a pronounced female predominance of 72%. Radiographic assessment revealed that 72% of patients presented with KL Grade 3 OA. This predominance of moderate-to-severe disease at presentation likely reflects delayed intervention and limitations of prolonged conservative management in our patient population. Prior studies indicate that Grade 3 OA – with preserved lateral compartment cartilage – represents an optimal window for HTO, as these patients demonstrate substantial pain relief and functional gains following realignment [11,12 ]. Pain outcomes demonstrated a predictable post-operative course. At 4 weeks, no statistically significant improvement in VAS scores was observed (mean change −0.20; P = 0.170). This early phase is typically dominated by surgical trauma, inflammatory responses, and periarticular soft-tissue edema, which may obscure the symptomatic benefits of mechanical realignment. Consequently, appropriate analgesic strategies and well-structured physiotherapy during this period are essential to sustain patient satisfaction and to avoid misattribution of early post-operative discomfort to surgical failure. From 6 weeks onward, a significant reduction in VAS scores was evident (mean decrease 1.12 at 6 weeks; P < 0.001), with progressive improvement noted at 12 and 18 weeks. By 18 weeks postoperatively, mean VAS scores had decreased by approximately 52% from baseline. This temporal pattern is consistent with reports by Niemeyer et al. and Akizuki et al., who noted that clinically meaningful pain relief after MOWHTO typically emerges after the initial post-operative inflammatory phase, once mechanical unloading of the medial compartment is established [9,13]. Similar sustained improvements in pain scores have been documented in medium- and long-term follow-up studies by van Raaij et al., Gaasbeek et al., and Bode et al., underscoring the durability of pain relief when accurate correction and stable fixation are achieved [10,14,15]. [Fig. 1]

Figure 1: Line graphs depicting changes in clinical outcomes following medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy. (a) Mean visual analog scale pain scores showing progressive reduction from the pre-operative period to post-operative follow-up. (b) Mean Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index scores demonstrating sustained improvement in functional status at 12 and 24 weeks postoperatively.

Functional recovery, evaluated using the WOMAC, showed a gradual, stepwise improvement over time. At 6 weeks, a modest but statistically significant reduction in WOMAC scores was noted (mean change 2.32; P = 0.022), likely attributable to reduced pain-related guarding and early improvements in joint kinematics, despite ongoing post-operative restrictions. More substantial improvements were evident at 12, 18, and 24 weeks, with mean WOMAC score reductions of 11.64, 21.92, and 35.56 points, respectively (all P < 0.001). By 24 weeks, overall functional status had improved by nearly 63% compared with baseline. This pattern of progressive functional recovery is consistent with the findings of Niemeyer et al., who reported continued functional gains up to 6–12 months following open-wedge HTO when structured rehabilitation protocols are followed. Early improvements are primarily driven by pain relief and gradual recovery of muscle strength, whereas later gains reflect ongoing bone remodeling, optimized joint biomechanics, and strengthening of the periarticular musculature [9]. The sustained reductions in VAS and WOMAC scores in our cohort indirectly suggest favorable biomechanical adaptation post-realignment and improvement in gait parameters due to normalization of load distribution across the knee joint [16]. Future studies incorporating objective gait assessment could quantify these changes directly and correlate them with clinical outcomes. [Fig. 2 and 3]

Figure 2: Clinical photographs of the patient in the standing position. (a) Pre-operative image showing bilateral varus knee alignment. (b) 4 months post-operative image demonstrating correction of lower limb mechanical axis following medial open-wedge high tibial osteotomy (left knee)

Figure 3: Standing photographs pre and post operative (at 5 months) depicting improved alignment and weight distribution.

Pre-operative correction planning was performed using the Miniaci method, as originally described by Miniaci et al., which enables precise calculation of the required wedge opening by projecting the mechanical weight-bearing axis through the Fujisawa point and determining the hinge-based angular correction. The intended post-operative mechanical axis was targeted to pass approximately 62.5% lateral to the tibial plateau width. In our series, the achieved mean post-operative varus angle was 2.4 ± 0.65°, closely approximating the planned correction and thereby confirming the reliability and reproducibility of the Miniaci technique in achieving accurate alignment. [4,17] Though we did not use bone substitutes or wedges in our series, several authors have reported satisfactory union rates and maintenance of correction with their use in open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. [18]

The post-operative alignment achieved in this study compares favorably with previously published literature, where most authors have reported a slight neutral to valgus correction following MOWHTO. et al. , Niemeyer et al. and Ghasemi et al. have demonstrated that maintaining correction close to the Fujisawa point—without excessive valgus—optimizes load redistribution while minimizing the risk of lateral compartment overload and subsequent progression of OA. We have maintained the weight-bearing axis through the Fujisawa point while avoiding incidences of non-union and lateral hinge fractures, supporting the adequacy of correction and reinforcing the importance of meticulous pre-operative planning to achieve biomechanically favorable outcomes [9,13,19]. [Fig 4]

Figure 4: Standing long-leg radiographs of the lower limbs. (a) Pre-operative radiograph showing varus mechanical axis deviation. (b) Post-operative radiograph demonstrating correction of the mechanical axis now passing through the Fujisawa point (left knee).

All patients received TomoFix plate fixation, chosen for its angular stability and biomechanical advantages. Large series have demonstrated that TomoFix fixation maintains correction reliably and is associated with fewer complications and better medium-term survival compared to alternative implants [20]. In our cohort, there were no instances of implant failure or loss of correction, allowing early mobilization and staged weight-bearing without increased risk. The stability provided by TomoFix likely contributed significantly to radiographic maintenance of alignment and clinical improvements. Randomized trials by Brouwer et al. comparing opening- and closing-wedge techniques have shown comparable clinical outcomes, with opening-wedge osteotomy offering advantages such as precise correction control and avoidance of fibular osteotomy. [21]

Lateral hinge fractures are a known risk in medial opening-wedge HTO, with reported incidence up to approximately 5%. Prophylactic measures – such as using a Kirschner wire near the lateral cortex to protect the hinge – can minimize this complication. In our series, no lateral hinge fractures occurred, reflecting meticulous intraoperative technique and careful execution of osteotomy [5].

Limitations and future directions

This study’s limitations include a modest sample size (n = 25) and follow-up primarily up to 24 weeks, limiting assessment of longer-term outcomes. Lack of objective gait analysis and advanced cartilage imaging (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging) precludes deeper insight into biomechanical and biological adaptation. Lack of a comparison group to analyse the different modalities of treatment also restricts our ability to conclude the superiority of the intervention. Future studies should involve larger cohorts with extended follow-up, comparative study designs, incorporation of gait biomechanics and imaging biomarkers, and evaluation of adjunctive biologic therapies to refine patient selection and perioperative protocols.

MOWHTO using TomoFix fixation in this selection of predominantly elderly patients with moderate-to-severe medial compartment knee OA and varus deformity resulted in reliable mechanical axis correction, significant pain relief beginning at 6 weeks postoperatively, progressive functional improvement through 24 weeks, and a low complication rate when meticulous surgical technique and structured rehabilitation were applied. These outcomes align with international literature and support MOWHTO as a valuable joint-preserving option in appropriately selected patients. Continued long-term follow-up will validate the durability of these benefits and guide strategies for earlier referral and potential biologic augmentation in this population.

Medial open wedge HTO is an effective joint-preserving procedure for carefully selected patients with medial compartment knee OA and varus malalignment, providing significant pain relief, functional improvement, and reliable restoration of lower limb alignment when meticulous planning and surgical technique are employed.

References

- 1. Coventry MB. Osteotomy of the upper portion of the tibia for degenerative arthritis of the knee. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1965;47:984-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Yadav R, Verma AK, Uppal A, Chahar HS, Patel J, Pal CP. Prevalence of primary knee osteoarthritis in the urban and rural population in India. Indian J Rheumatol 2022;17:239-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16:494-502.. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Miniaci A, Ballmer FT, Ballmer PM, Jakob RP. Proximal tibial osteotomy. A new fixation device. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;246:250-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Miltenberg B, Puzzitiello RN, Ruelos VC, Masood R, Pagani NR, Moverman MA, et al. Incidence of complications and revision surgery after high tibial osteotomy: A systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2024;52:258-68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Coventry MB, Ilstrup DM, Wallrichs SL. Proximal tibial osteotomy. A critical long-term study of eighty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:196-201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Song EK, Seon JK, Park SJ. How to avoid unintended increase of posterior slope after opening wedge high tibial osteotomy: Importance of sagittal alignment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:1474-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hernigou P, Medevielle D, Debeyre J, Goutallier D. Proximal tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis with varus deformity. A ten to thirteen-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:332-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Niemeyer P, Koestler W, Kaehler M, Feucht M, Muench LN, Südkamp NP. Two-year results of open-wedge high tibial osteotomy with fixation by medial plate fixator for medial compartment arthritis with varus malalignment of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:470-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bode G, Von Heyden J, Pestka J, Schmal H, Salzmann G, Südkamp N, et al. Prospective 5-year survival rate data following open-wedge valgus high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:1949-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Naudie DD, Amendola A, Fowler PJ. Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy for symptomatic hyperextension-varus thrust. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1371-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Akizuki S, Shibakawa A, Takizawa T, Yamazaki I, Horiuchi H. Relationship between patient satisfaction and the Oxford Knee Score after high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:1042-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Van Raaij TM, Brouwer RW, De Vlieger R, Verhaar JA. Medium-term follow-up of a medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy using a locking plate. Knee 2008;15:111-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Gaasbeek RD, Nicolaas L, Rijnberg WJ, Van Loon CJ, Van Kampen A. Correction accuracy and collateral laxity in open versus closed wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18:688-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Lee OS, Ahn S, Lee YS. Effect and safety of early weight-bearing on the outcome after open-wedge high tibial osteotomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2017;137:903-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Fujisawa Y, Masuhara K, Shiomi S. The effect of high tibial osteotomy on osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1979;61:374-83 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Saragaglia D, Blaysat M, Inman D, Mercier N. Outcome of opening wedge high tibial osteotomy augmented with a Biosorb wedge and fixed with a plate and screws. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018;104:479-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Ghasemi SA, Murray BC, Buksbaum JR, Shin J, Fragomen A, Rozbruch SR. Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: Planning and improving outcomes: Case series and literature review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2022;36:102085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Amzallag J, Pujol N, Maqdes A, Beaufils P. Outcome of open-wedge high tibial osteotomy augmented with a Biosorb wedge and fixed with a plate and screws. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015;101:553-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Brouwer RW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Van Raaij TM, Verhaar JA. Osteotomy for medial compartment arthritis of the knee using a closing wedge or an opening wedge controlled by a Puddu plate: A randomized controlled trial. Knee 2006;13:361-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Lee JH, Choi YS, Bae DK, Song SJ, Yoon JR, Kim TY. Changes in lower limb alignment and posterior tibial slope after open wedge high tibial osteotomy with a locking plate. Clin Biomech 2017;42:38-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]