Despite being resolved with a simple resection surgery, a forearm glomangioma is a rare tumor that is easily misdiagnosed and a cause of chronic forearm pain refractory to conservative treatment.

Mr. Ethan Kosco, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, 3000 Arlington Ave, Toledo, Ohio, 43614. E-mail: ekosco@rockets.utoledo.edu

Introduction: Glomangiomas are rare vascular tumors derived from the vascular component of glomus bodies. Because glomus bodies play an important role in thermoregulation in the digits of the hand and foot, glomus tumors predominantly arise in these locations. Only six incidents of glomangiomas have arisen in the forearm since 1991. In nearly every case, the tumor was associated with extreme tenderness to palpation and pain with the use of the forearm. The diagnosis was delayed up to 21 years due to the low clinical suspicion of this type of tumor. However, eventual diagnosis and surgical management led to immediate resolution of pain in the forearm.

Case Report: We report the diagnosis and treatment of a 52-year-old male who presented with a 5-year history of volar mid-forearm pain refractory to conservative treatment. Diagnostic evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging and histology identified the tumor as a glomangioma.

Conclusion: Surgical excision completely resolved the patient’s symptoms by the 2-week follow-up.

Keywords: Glomangioma, forearm tumor, surgical resection, orthopedic surgery, magnetic resonance imaging.

A glomus body is a thermoregulating arteriovenous anastomosis most commonly present in the subungual regions of the fingers and toes. Their primary function is to constrict and prevent heat loss in cold temperatures [1]. These units exist in the dermis and comprise smooth muscle, glomus cells, and vasculature surrounded by a connective tissue capsule [2]. Glomus tumors can arise from hyperplasia of any of these three structures; solid tumors account for 75% of glomus tumors, glomangiomas (vascular) represent 20%, and glomangiomyomas (smooth muscle) make up 5% [1]. Glomus tumors comprise 1–2% of all soft-tissue tumors and 1–5% of soft-tissue tumors in the hand [1,3]. Because of their natural physiologic role in the distal extremities, it is extremely rare for these tumors to present extra digitally. They have been reported to present in various body parts such as the foot, stomach, colon, mesentery, and bone in patients ranging from infants to the elderly [3,4]. One study examined a potential genetic association of glomus tumors in family members each presenting with multiple glomus tumors [5]. After a careful literature review, only six cases of forearm glomangiomas have been reported since 1991 [3-9]. Each of these cases describes an inexplicable and severe point tenderness on the forearm that was refractory to conservative measures, medication, and multiple specialty visits. Diagnosis of the glomangioma was delayed for up to 20 years due to low clinical suspicion of the tumor. In each case, the severe point tenderness immediately resolved after a simple surgical excision of the tumor. In this paper, we report the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of a patient with a solitary forearm glomangioma.

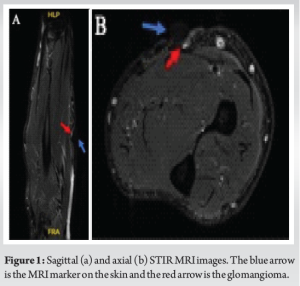

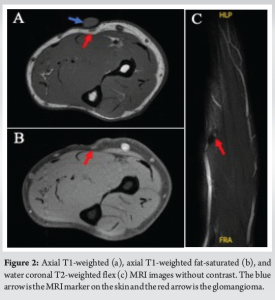

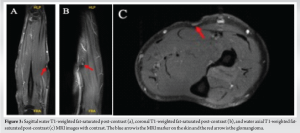

A 52-year-old male with no significant medical history presented to the outpatient clinic for a 5-year history of pain in the right volar mid-forearm region. The pain was aggravated by palpation and occasionally worsened with activity. He denied any associated symptoms, including weakness, stiffness, numbness, or tingling. No mass was palpable on the volar forearm, but the patient demonstrated significant well-localized point tenderness. The wrist and fingers had a full range of motion without any pain. There was also no pain with resisted motion of the wrist or digits. Tinel’s sign was also negative along the forearm. Two view X-rays of the right forearm displayed no bony abnormalities. The patient was advised to perform conservative pain management, including topical anti-inflammatory medication and physical therapy. Three months later, the patient returned with no improvement in symptoms. Subsequent short tau inversion recovery (STIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images and MRI with and without intravenous contrast revealed a 3–5 mm nodular density in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of the anterior aspect of the right mid-forearm (Fig. 1-3). The mass was bright on T2 and STIR, dark on T1, and enhanced with contrast.

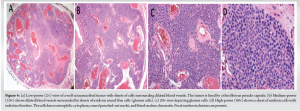

There was no evidence of intramuscular hemorrhage or bony pathology. The patient elected to attempt a corticosteroid injection instead of undergoing an exploratory surgery. The area of tenderness was palpated and injected with 1 ml of 1% lidocaine and 1 ml of kenalog 10 mg/ml. The patient tolerated the injection and was advised to follow up for discussion of possible surgical intervention if the pain persists. The patient returned approximately 3 months later and reported that the steroid injection only provided short-term relief before the pain returned to baseline. The patient agreed to undergo surgical excision at this time. Under local anesthetic, a 2 cm volar forearm incision was made, and a 3 mm red-purple round, well-circumscribed vascular mass with several small connecting vessels was found. The mass was excised along with some of the surrounding subcutaneous tissue. The rest of the region was carefully palpated, and no additional masses were identified. The mass was sent to pathology and diagnosed as a glomangioma. Histology showed a highly vascularized well-circumscribed tumor with sheets of glomus cells (Fig. 4). There were no signs of malignancy in the histology images.

Two weeks post-operative, the patient reported a complete resolution of symptoms. The patient could perform all activities as tolerated and there was no longer any tenderness to palpation.

Glomangiomas are vascular tumors that comprise 1–2% of all soft skin tumors and 20% of glomus tumors. They are derived from the vascular component of glomus bodies and function as thermoregulatory units in the subungual regions of the distal extremities. These tumors may arise due to an inherited loss of function mutation in glomulin, a gene essential to vascular development. This autosomal dominant mutation accounts for 38–68% of glomangiomas. Patients with glomangiomas may experience a classic triad of hypersensitivity, intermittent pain, and pinpoint pain. The pain may be elicited by cold temperature or pressure. Hildreth’s test is a clinical sign of glomangioma. A positive test is elicited when the patient experiences a reduction in pain or tenderness at the site of the lesion after exsanguination through tourniquet application. The Love’s pin test is another diagnostic physical examination for glomus tumors. It tests for point tenderness using a pinhead or pencil tip to apply pressure to a suspected area [10]. Ultrasound and MRI can confirm the lesion’s location, size, and shape, whereas X-ray may show bony defects. MR angiography can demonstrate the vascularity of the tumor. However, these forms of imaging are often not specific. Ultrasound is considered to be the best imaging modality when evaluating glomus tumors as it can help differentiate them from other soft-tissue tumors, such as arteriovenous malformations or hemangiomas [11,12].While a thorough history, physical examination, and imaging are important factors in diagnosis, definitive diagnosis is made through histological examination. The gross pathology of glomangiomas appears as blue-purple hyperkeratotic, papular lesions with a cobblestone appearance. Microscopic examination of the tumors displays glomus cells surrounding dilated blood vessels. The tissue may stain positive for vimentin, calponin, and SMC alfa-actin [13]. Asymptomatic lesions are treated with observation. Symptomatic lesions are treated with surgical excision which typically results in the immediate resolution of symptoms. While surgical excision is the preferred treatment for painful lesions, other options, such as electron beam radiation, sclerotherapy, and CO2 laser treatment are being studied [14]. Following surgical excision, glomangiomas have a 10–33% risk of recurrence [2]. Most of these tumors are benign with a low risk of malignancy; however, there have been reports of malignant cases [15]. Metastasis is extremely rare. It is uncommon for glomangiomas to present extra digitally. About 75% of glomangiomas occur in the hands [14]. This, coupled with their non-specific findings, can often lead to misdiagnosis or delays in diagnosis and treatment. The case we presented represents the delay in diagnosis and treatment if glomangioma is not considered in the differential diagnosis. This patient had a 5-year history of chronic pain and was evaluated by multiple clinicians without a successful diagnosis or treatment due to the rarity of glomangiomas presenting extra-digitally. The patient received conservative management with NSAIDs, steroid injections, physical therapy over 5 years, and multiple clinic visits before finally resorting to surgical resection. Due to the condition’s rarity, the resected tumor was not suspected to be a glomangioma until the pathology department prepared the tissue sample and observed numerous glomus cells surrounded by the vasculature. Previous reports have noted patients waiting over 20 years and visiting several specialties, such as neurologists, surgeons, orthopedists, and primary care physicians until a simple excision resolves symptoms [9]. Therefore, we recommend forearm glomangiomas always be on the differential diagnosis for localized pain in the forearm.

Glomangiomas are rare tumors derived from the vascular component of glomus bodies – thermoregulating arteriovenous anastomosis most commonly present in the subungual regions of the fingers and toes. They are associated with exquisite tenderness to palpation and dull pain with overuse. It presents on MRI as a nodular density in the superficial tissue that typically does not invade the muscle fascia. Although diagnosis is difficult due to the low prevalence of the tumor and non-specific symptoms, treatment with surgical excision results in immediate resolution of symptoms. We presented the case of a 52-year-old male with a 5-year history of volar mid-forearm pain due to a glomangioma. This case provides a detailed time course for the initial differential diagnoses, radiographic imaging, conservative measures, and ultimate surgical procedures with histological images. The pain was immediately resolved with a brief excision surgery. Therefore, we would like to report this case to emphasize the importance of including this type of tumor in the differential for severe, medically refractive forearm pain that is associated with chronic impairment in the quality of life.

Forearm glomangiomas are exquisitely tender tumors often present in the distal extremities. In the past 30 years, there have been several instances of glomangiomas appearing in the forearm. In each case, patients suffered from chronic forearm pain that went undiagnosed for up to 20 years. We present the clinical presentation, radiographic findings, and simple surgical procedure that results in the complete resolution of symptoms in patients with forearm glomangiomas. We encourage orthopedic surgeons to add the diagnosis to their differential for patients suffering from chronic forearm pain.

References

- 1.Sethu C, Sethu AU. Glomus tumour. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016 Jan;98(1):e1-2. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0005. PMID: 26688416; PMCID: PMC5234378. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 2.Mohammadi O, Suarez M. Glomus cancer. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557496 Last accessed 22 July 2024. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Munde SL, Kamra HT, Singh K, Kaur S, Kundu P. RT glomangioma on right forearm - a rare case report. J Krishna Inst Med Sci Univ 2016;5:141-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Lee SK, Song DG, Choy WS. Intravascular glomus tumor of the forearm causing chronic pain and focal tenderness. Case Rep Orthop 2014;2014:619490. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Conant MA, Wiesenfeld SL. Multiple glomus tumors of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1971;103:481-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Lee S, Le H, Munk P, Malfair D, Lee CH, Clarkson P. Glomus tumour in the forearm: A case report and review of MRI findings. JBR-BTR 2010;93:292-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Acebo E, Val-Bernal JF, Arce F. Giant intravenous glomus tumor. J Cutan Pathol 1997;24:384-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Beham A, Fletcher CD. Intravascular glomus tumour: A previously undescribed phenomenon. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1991;418:175-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Singh D, Polineni S, Anurshetru B, Shalini A. Extradigital glomus tumor of left forearm: An unusual cause for persistent forearm pain. Indian J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2020;7:309-11. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Giele H. Hildreth’s test is a reliable clinical sign for the diagnosis of glomus tumours. J Hand Surg Br 2002;27:157-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Höglund M, Muren C, Brattström G. A statistical model for ultrasound diagnosis of soft-tissue tumours in the hand and forearm. Acta Radiol 1997;38:355-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Fan Z, Wu G, Ji B, Wang C, Luo S, Liu Y, et al. Color Doppler ultrasound morphology of glomus tumors of the extremities. Springerplus 2016;5:1319. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Brouillard P, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Enjolras O, Ghassibé M, Warman ML, et al. Mutations in a novel factor, glomulin, are responsible for glomuvenous malformations (“glomangiomas”). Am J Hum Genet 2002;70:866-74. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.De Souza NG, Nai GA, Wedy GF, de Abreu MA. Congenital plaque-like glomangioma: Report of two cases. An Bras Dermatol 2017;92:43-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, Weiss SW. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: Analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]