The intention of this article is to educate sports medicine and orthopedic providers regarding a novel injury mechanism to the femoral nerve.

Mr. Phillip Karsen, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Division of Sports Medicine, 5779 E Mayo BLVD, Phoenix AZ 85054. E-mail: Karsen.Phillip@mayo.edu

Introduction: Femoral nerve injury is a recognized complication of abdominal, pelvic, and orthopedic surgeries. It can also occur due to pelvic fractures, intra-abdominal trauma, and hip injuries. These injuries often result in pain, weakness, and difficulty with ambulation, significantly impacting a patient's quality of life.

Case Report: We report the case of a 72-year-old male who developed femoral nerve palsy while exiting a hot tub. The unusual mechanism of injury initially led to a missed diagnosis, delaying appropriate treatment. Following an extensive diagnostic workup, femoral nerve palsy was identified as the cause of his disability. Timely intervention ultimately led to the resolution of his symptoms.

Conclusion: This case highlights a novel mechanism of femoral nerve palsy and underscores the importance of prompt diagnosis for optimal outcomes. Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for rare injury mechanisms to avoid delays in treatment.

Keywords: Femoral nerve, palsy, nerve injury.

Injury to the femoral nerve is a known complication of orthopedic, gynecologic, and abdominal surgery and accounts for 60% of all femoral nerve injuries [1]. Other causes include lacerations, hematoma from sports injury, tumors, and spinal cord surgery [2]. Femoral nerve palsy can cause symptoms ranging from mild sensory changes to a complete inability to extend the knee. This case demonstrates a femoral nerve injury from a forced hyperextension moment at the hip. To our knowledge, this is a novel injury mechanism that has not previously been described in the literature.

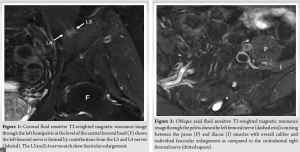

A 72-year-old male with a past medical history of a right knee medial meniscal tear and chondromalacia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease status post placement of two right coronary artery stents, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented to his PCP for evaluation of persistent acute left knee pain. He reported that 5 weeks prior he had slipped getting out of his hot tub. He described a sudden split motion with extreme hyperextension of the left hip with hyperflexion of the right hip. After, he experienced sudden bilateral knee pain predominantly in the left knee with no associated edema or bruising. The pain in the right knee resolved without treatment. His chief complaint was an inability to extend his knee or lift his leg, which unfortunately caused him to fall 4 days before the visit. Otherwise, he was in his normal state of health. On examination, he was noted to have tenderness to the proximal medial collateral ligament, iliotibial band, patella tendon, and quadricep tendon. There was no swelling or deformity and he demonstrated full range of motion. Motor testing demonstrated 1/5 strength to left knee extension and hip flexion. A quadriceps rupture was suspected. Referrals were placed for a left knee magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a consultation with the orthopedic department for further evaluation. The patient was then seen in the orthopedic clinic the following week. He reported continued left knee pain and weakness. The examination revealed no ligamentous injury. There was no defect to the quadricep tendon but there was noticeable quadricep atrophy. A neurologic examination showed numbness to the medial aspect of the knee, and he demonstrated an inability to fire the quadriceps. He also described burning pain radiating down the front of his leg. Radiographs of the left knee showed no acute process, specifically no patella baja or alta. MRI of the knee showed no evidence of a quadricep rupture. The MRI did show chronic degenerative changes in the knee. After imaging review and evaluation, femoral nerve palsy was suspected. The patient was sent for an electromyography (EMG) and an MRI of the femur to assess the femoral nerve’s continuity. He was also referred to physical therapy for quadriceps strengthening. Gabapentin therapy was started to help with continued pain. The EMG and femur MRI were completed the following day. The EMG showed an active and severe left L3 lumbar radiculopathy. The MRI showed no signs of injury to the left thigh nerves. After these findings were reviewed an MRI of the lumbar spine was placed. The MRI of the lumbar spine was completed the following week. This showed multilevel degenerative changes, spinal canal narrowing, and bilateral neuroforaminal narrowing at L4-L5. This prompted an order for a lumbar plexus MRI to be completed the next day. This demonstrated injury to the pelvic portion of the femoral nerve with mild enlargement and higher-than-normal signal intensity. MRI Fig. 1 and 2 show L3/L4 fascicular enlargement consistent with femoral nerve injury.

A second visit to orthopedics, this time with a nerve specialist, was completed approximately 7 weeks after his injury. He reported continued significant disability. Due to irregularities with the lumbar EMG and findings of the lumbar plexus MRI, an additional EMG was performed in neurology before the visit, showing signs of a left lumbar plexopathy. Examination revealed mild flickering of the quadriceps muscle. A Tinel’s over the femoral nerve was negative. Due to the location of the nerve injury, decompressive surgery was not recommended. Optimism for eventual recovery was discussed as the recent EMG showed motor unit potentials being present. Physical therapy and bracing were encouraged. The patient began physical therapy approximately 10 weeks after his injury. He was found to have continued weakness in the hip flexor, adductors, and quad. He attended physical therapy 3 times. After his third visit, he had a follow-up with orthopedics. He showed improved muscle strength from the initial visit and was encouraged to continue with physical therapy. One month later he underwent a follow-up EMG. Compared to his prior studies, he was found to have significantly improved re-innervation changes.

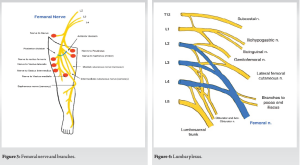

Femoral neuropathy was first described in 1822 by Descartes as anterior crural neuritis [4] with Gumpertz describing post-operative femoral nerve lesions in 1896 [1]. Femoral neuropathy is uncommon and is most often iatrogenic [1] with presentation ranging from mild numbness to inability to ambulate. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a traumatic femoral nerve palsy with this mechanism of injury. No injuries of this type were found on PubMed and Google Scholar going back 30 years. Our purpose with this report was to educate on this unique injury mechanism. The femoral nerve has an anterior and posterior branch and provides both motor and sensory innervation to the lower extremities (Fig. 3). The femoral nerve arises from the lumbar plexus and is its largest branch [4] (Fig. 4). The femoral nerve is derived from the second, third, and fourth lumbar spinal nerves and unites at the psoas muscle and continues into the deep thigh deep to the inguinal ligament and lateral to the femoral sheath [4,5]. The femoral nerve provides sensation to the anteromedial thigh [6] where it terminates as the saphenous nerve. It is predominantly a motor nerve [7], supplying motor innervation to all four quadricep muscles, sartorius, pectinous, psoas, and iliacus muscles [4,8].

It is well established that the most common cause of femoral nerve palsy is iatrogenic from orthopedic, abdominal, and pelvic surgeries. As such, there is little literature that discusses a femoral nerve palsy that is not iatrogenic. Iatrogenic orthopedic causes include stretching, lengthening of the limb, hematomas, compression from retractors, traction, heat injury from cementation, surgical positioning, injection into the nerve, tourniquet use, and casting/splinting [1,9]. Injury rates to the femoral nerve after hip arthroplasty range from 0.3 to 3.7% [1,4] whereas Grunson and Moed reported 2/726 acetabular fracture fixation cases resulting in femoral nerve injury. During orthopedic cases, care should be taken to avoid direct injury, compression, and stretch to the femoral nerve. Careful positioning of the extremity should also be considered to protect from injury. After an injury occurs the patient presentation is quite variable. Symptoms will range from mild paresthesia to significant sensory and motor loss [6]. Pain is often neuropathic and will require medications specific for neuropathic pain [10]. Unexpected buckling of the knee is often the first symptom noted by a patient after an iatrogenic injury [3,6], occurring the 1st time the patient tries to stand after surgery. In worst-case scenarios, the patient will be unable to ambulate, climb stairs, and rise from a seated position. This will undoubtedly cause issues with activities of daily living (ADLs) and impact lifestyle. Rarely, injury to the femoral nerve will be associated with severe and sometimes fatal vascular injury [8]. Although uncommon, post-operative femoral nerve palsy can result in a permanent deficit. Most of the available literature regarding workup, treatment, and management is focused on iatrogenic injury. Upon identification of an injury, it is important to do a thorough examination to determine the extent and level of disability. Physical examination should assess strength and sensation throughout the extremity and include a Tinel sign. Any movement or preserved sensation indicates an incomplete lesion [10] and there will be a higher likelihood of recovery. MRI can be used to look at any disruption of the nerve and assess for hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, etc. that could be injuring the nerve. EMG can help identify the level of injury and can be used to assess improvement; this should be done at 6, 12, and 24 weeks from injury [4]. If the injury is iatrogenic, radiographs and computed tomography should be used to look for hardware complications, extruded cement, hematoma, etc. that would need immediate surgical correction [8]. In cases of a more distal injury, Gruber et al. report ultrasound being useful for determining nerve discontinuity and compression 10 cm above to 5 cm below the inguinal ligament. No matter the cause or level of injury, physical therapy should be initiated immediately. Physical therapy will be focused on preventing atrophy, reducing the risk of deep vein thrombosis [11], and preventing joint stiffness and loss of motion. Modalities include orthosis, stretching, and muscle stimulation. In most cases, the full function will return in a few weeks with aggressive physical therapy [1]. Pain should be addressed and treated aggressively. Medications appropriate for this include tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, anti-convulsants, baclofen, gabapentin, and pregabalin [10]. Surgery is reserved for cases with a strong suspicion of direct nerve injury [3] or failure to improve after 12 – 24 weeks [4].

This case demonstrates a novel mechanism of femoral nerve injury yet to be reported in the literature. Early recognition and treatment of these injuries is important as delayed treatment may lead to detrimental loss of function. Luckily, most of these injuries resolve with physical therapy and time without residual loss of function. Our patient had improved physical findings and electromyographic studies 14 weeks after his injury, with a return to his normal function.

This case report demonstrates a novel injury mechanism to the femoral nerve. To our knowledge, this is the only case report of its kind. PubMed and Google Scholar databases were searched going back 30 years.

References

- 1.Gibelli F, Ricci G, Sirignano A, Bailo P, De Leo D. Iatrogenic femoral nerve injuries: Analysis of medico-legal issues through a scoping review approach. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2021;72:103055. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Refai NA, Black AC, Tadi P. Anatomy, bony pelvis, and lower limb: Thigh femoral nerve. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk556065 [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 22]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Al-Ajmi A, Rousseff RT, Khuraibet AJ. Iatrogenic femoral neuropathy: Two cases and literature update. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2010;12:66-75. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Ducic I, Dellon L, Larson EE. Treatment concepts for idiopathic and iatrogenic femoral nerve mononeuropathy. Ann Plast Surg 2005;55:397-401. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Gustafson KJ, Pinault GC, Neville JJ, Syed I, Davis JA Jr., Jean-Claude J, et al. Fascicular anatomy of human femoral nerve: Implications for neural prostheses using nerve cuff electrodes. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009;46:973-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Wilbourn AJ. Iatrogenic nerve injuries. Neurol Clin 1998;16:55-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Nielsen KC, Klein SM, Steele SM. Femoral nerve blocks. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag 2003;7:8-17. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Kline DG. Intrapelvic and thigh-level femoral nerve lesions: Management and outcomes in 119 surgically treated cases. J Neurosurg 2004;100:989-96. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Antoniadis G, Kretschmer T, Pedro MT, König RW, Heinen CP, Richter HP. Iatrogenic nerve injuries: Prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. Deutsch Ärztebl Int 2014;111:273-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Campbell WW. Evaluation and management of peripheral nerve injury. Clin Neurophysiol 2008;119:1951-65. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Moore AE, Stringer MD. Iatrogenic femoral nerve injury: A systematic review. Surg Radiol Anat 2011;33:649-58. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Gruson KI, Moed BR. Injury of the femoral nerve associated with acetabular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85:428-31 [Google Scholar | PubMed]