Minimally invasive spinal fusion appears to be a safe and effective treatment for Grade I and II spondylolisthesis, with potential advantages in operative time and hospital stay duration compared to open surgery.

Dr. Vikramaditya Rai, Department of Orthopaedics, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College and Hospital, Tanda at Kangra, Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: raizobiotec@gmail.com

Introduction: In recent years, there has been a growing utilization of minimally invasive (MI) techniques, which provide the potential advantages of minimizing surgical stress, post-operative pain, and hospitalization duration. Nevertheless, the existing body of literature primarily comprises of studies conducted at a single medical site, which are of low quality and lack a comprehensive analysis of treatment techniques exclusively focused on spondylolisthesis. We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to compare minimally invasive surgery (MIS) and open surgery (OS) spinal fusion outcomes for the treatment of spondylolisthesis. OS spinal fusion is an interventional option for patients with spinal illness who have not had success with non-surgical treatments.

Materials and Methods: This systematic review of the literature regarding MI and OS spinal fusion for spondylolisthesis treatment was performed using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis guidelines for article identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. Electronic literature search of Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases yielded 1078 articles. These articles were screened against established criteria for inclusion into this study.

Results: A total of eight retrospective and four prospective articles with a total of 3354 patients were found. Reported spondylolisthesis grades were I and II only. Overall, MI was associated with lower operative time (mean difference [MD], −6.44 min; 95% confidence interval [CI], −45.57–32.71; P = 0.0001) and shorter length of hospital stay (MD, −0.49 days; 95% CI, −0.58 to −0.40; P = 0.000). There was no significant difference overall between MIS and OS in terms of functional or pain outcomes. Rates of complications were not significantly different between the MI group and the OS group, though overall 75 and 153 complications were observed in MI group and OS group.

Conclusion: Available data indicate that MI spinal fusion is a secure and efficient method for managing Grade I and Grade II spondylolisthesis. Furthermore, whereas prospective trials establish a connection between MI and improved functional outcomes, it is necessary to conduct longer-term and randomized trials to confirm any correlation identified in this study.

Keywords: Minimally invasive spinal fusion, open surgical spinal fusion, lumbar spine fusion, spondylolisthesis, functional outcomes, complication rates, systematic review, meta-analysis.

Spondylolisthesis, a condition where a vertebral body is displaced, can lead to radiculopathy, neurogenic claudication, or mechanical low back discomfort [1]. There are two distinct causes of spondylolisthesis: Degenerative spondylolisthesis and isthmic spondylolisthesis. Studies indicate that surgery may be a feasible option for individuals whose spondylolisthesis does not respond to conservative treatment, as it has the potential to improve the patient’s quality of life [2-5]. Historically, open surgery (OS) with direct decompression and instrumented fusion has been the preferred surgical treatment for degenerative and isthmic spondylolisthesis, as it effectively addresses the instability caused by spinal slippage. Various fusion techniques include anterior lumbar interbody fusion, lateral interbody fusion, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), and posterior lumbar fusion (PLF). The prevalence of lumbar spine fusions rose from 9/100,000 person-years in 1997 to 30/100,000 person-years in 2018 [6]. Among women aged over 75 years, there was a 4-fold increase in the occurrence of lumbar spine fusions [5]. According to global estimates, almost 313 million procedures are conducted every year [7], with around 500,000 of these being lumbar spine surgeries in the United States [8]. Approximately 80% of individuals who undergo spine surgery encounter post-surgery discomfort, while over 20% of them will continue to experience severe post-surgical pain. In the last decade, the MI technique has undergone significant advancements, offering notable benefits such as reduced pain and improved functionality after surgery, faster recovery, decreased blood loss, minimized harm to soft tissues, and preservation of the structural integrity of the paraspinal region while minimizing the formation of scar tissue [9]. The benefits of these advantages are particularly crucial when dealing with spondylolisthesis, as an open approach might exacerbate the instability of the facet joints, ligamentous structures, and muscles, which play a key role in providing support. Multiple studies have examined the perioperative, functional, and pain outcomes of minimally invasive (MI) versus OS for the treatment of common lumbar degenerative conditions including spinal stenosis, disk disease, and spondylolisthesis. As far as we know, only one review on spondylolisthesis has investigated the disparities in pain, function, and perioperative results between MI and OS [10]. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of MI and OS treatment on spondylolisthesis and analyze the results in comparison to other degenerative conditions affecting the lower back.

Search strategy

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses were used in this investigation. In January 2023, two reviewers (SWM and QAA) conducted independent electronic searches using PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, and Scopus, without any time constraints. ACP journal club trial registries, dissertations, conference proceedings, and the Database of Abstracts of Review of Effectiveness were also examined for unpublished material. Citations written in English alone were taken into account. In every possible combination, the following terms were utilized in the search strategy as either keywords or Medical Subject Headings: “minimally invasive”/“minimal access,” “lumbar spine”/“lumbar vertebra,” “spinal fusion”/“surgical procedure,” and “spondylolisthesis.” The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to evaluate the generated reference lists after they had been compared and examined for possible relevancy.

Selection criteria

The studies included in this meta-analysis and systematic review examined the effectiveness of spinal fusion procedures for treating spondylolisthesis by assessing overall rates of operative success and occurrence of major complications. In this study, complete spinal exposure was necessary for OS treatments, while MI methods included percutaneous, mini-open, and muscle-splitting approaches to the spine. The study’s inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) A definitive diagnosis of either degenerative or isthmic lumbar spondylolisthesis only; (2) at least one of the following outcomes measured by the Oswestry disability index (ODI) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS), respectively, including scores for functional ability and pain before and after surgery; and (3) a study design that directly compares different groups or treatments. The exclusion criteria included trials with < 20 patients in each arm, cohorts with lumbar degenerative disorders other than spondylolisthesis, case reports and series without a comparison group, as well as editorials, reviews, opinion pieces, and commentary articles. To ensure that no relevant research was missed, a thorough examination of reference lists was conducted manually.

Data extraction

The data gathered included information on methodology, study design, patient demographics, operation aspects (such as the type of procedure and number of fused vertebral levels), intraoperative blood loss, and operative outcomes (such as length of hospital stay following surgery). The study’s conclusion also included reporting the functional findings, measured by the ODI on a scale ranging from 0% to 100%. The rating method requires individuals to have a bed-bound status ranging from 80% to 100%, and a minor impairment ranging from 0% to 20%. The back pain outcome determined by the VAS was also revealed at the completion of the trial follow-up. The VAS is a numerical scale ranging from 1 to 10, where a score of 1 indicates the absence of pain and a score of 10 represents the highest imaginable amount of misery. Other events that were described included wound infection, revision surgery, and intraoperative durotomy. If the mean and standard deviation of the numbers were not given, we used the available technique and graphs to generate the most accurate estimations [11,12]. Two reviewers, VR and SK, collected data from papers, tables, and figures, while another reviewer, CM, ensured the accuracy of the data entry.

Cohort comparison

The patient demographics from the studies were analyzed to determine the average age, percentage of males, and number of surgery levels. This analysis was done using a weighted distribution method to account for variations in sample sizes. The continuous variables were compared using a two-sample t-test, while the number of surgical levels was compared using a two-proportion z-test. Statistical significance was determined for a two-tailed value of <0.05.

Meta-analysis of clinical outcomes

The summary statistics utilized were the odds ratio (OR), mean difference (MD), or weighted MD. The current study examined the efficacy of Cohen’s technique utilizing the common-effect inverse-variable model. The I2 statistic was employed to assess the fraction of overall variation among studies that can be attributable to heterogeneity rather than random chance. Values that are >50% are considered to be suggestive of substantial heterogeneity. Given the absence of raw data, it was not possible to carry out comprehensive analyses that consider confounding factors. The P values were computed using a two-tailed test. A pooled estimate of treatment impact for continuous variables was computed by calculating the MD and 95% confidence interval (CI) between outcomes in the MIS and open cohorts. This was done using an inverse-variance weighting method with a random effects model. To compare the outcomes of dichotomous variables, such as complications, we generated a risk ratio and 95% CI using the Mantel-Haenszel method using a random effects model. The random effects model, in contrast to a fixed-effects model, yields a more cautious estimation of the treatment effect [13]. The use of this statistical approach was considered suitable due to the assumed diversity among the experiments. The statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager Version 5.3.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK). Forest plots have been generated to visually present the findings of each study and pooled estimations of the impact.

Evidence quality

Utilizing the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) process, two reviewers (VR and CM) evaluated the quality of evidence for each study separately. A total rating of high, moderate, low, or extremely low was assigned to each study according to its design, limits, findings, level of accuracy, and supporting documentation. Discrepancy cases were settled by conversation.

Literature search

A total of 1078 papers were found using our search strategy (Fig. 1). The titles and abstracts of the 746 papers were subjected to inclusion/exclusion criteria following the removal of 332 duplicate publications. A full-text analysis was conducted on 17 of the articles that came from this. The current review includes 12 articles for both quantitative and qualitative analysis. All the included studies were observational cohort studies conducted at a single and multiple institutions; four of the studies were prospective [14-17] and eight of the studies were retrospective [18-25] (Table 1).

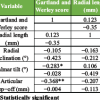

Patient demographics

A total of 3354 patients were included in the analysis of all studies. Among them, 1087 patients (32.44%) underwent MI for spondylolisthesis treatment, whereas 2267 patients (67.6%) underwent OS for spinal fusion. Table 2 presents comparative features. The mean age in the MI group was 59.15±9.96 years, while in the OS group, it was 59.04±8.88 years. The proportion of males in the MI group varied between 27% and 68%, while in the OS group it ranged from 22% to 74%. The mean number of fused levels ranged from 1 to 1.13 levels in the MI group and from 1 to 1.9 levels in the OS group. The fusion rates reported by both the MI and OS groups ranged from 90.2% to 100%. There was no statistically significant difference in the indicated characteristics between the MIS and OS groups. Four cohort studies examined both isthmic and degenerative spondylolisthesis, while the other investigations focused solely on degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Grade of spondylolisthesis

Eleven studies reported the severity of spondylolisthesis in their groups using the Meyerding classification (Table 2). Out of the total, five studies were classified as Grade I, whilst six studies were classified as both Grade I and Grade II. Only lower grades were taken into account.

Procedure type

Ten studies exclusively utilized TLIF for spinal fusion, whereas two studies employed a combination of TLIF, PLIF, and PLF for both MI and OS (Table 2).

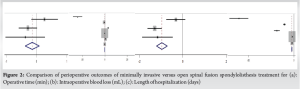

Operative time

Operative time data could be extracted from nine studies (Fig. 2A) due to the availability of sufficient data. There was no substantial disparity in general between the MI and the OS group. Nevertheless, patients with OS in both the prospective and retrospective cohort studies experienced longer surgical procedures compared to MI patients, with average durations of 2085 min against 188 min for prospective trials and 185 min versus 176 min for retrospective cohorts.

Intraoperative blood loss

Eight studies provided sufficient data to quantify the amount of blood lost after surgery (Fig. 2B). In the MI group, the average volume of blood loss was 210.35 mL, compared to 339.56 mL in the OS group. The disparity was significant (P = 0.0000).

Length of hospitalization (LOH)

Seven studies provided adequate data on the LOH (Fig. 2C). The mean duration of LOH was 3.99 days in the MI group compared to 5.24 days in the OS group. The difference was significant (P = 0.000).

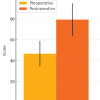

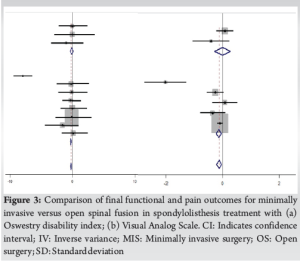

ODI

Eleven studies provided sufficient data to get final ODI scores (≥12 months) as a measure of disability (Fig. 3A). There was no significant disparity between the MI group and the OS group as a whole (Table 3). Nevertheless, patients with MI who participated in both prospective and retrospective cohort studies exhibited markedly lower final scores on the ODI compared to patients with OS. The weighted MD for prospective studies was −0.11 (95% CI: −0.35–0.11), with pooled means of 25.7 and 30.7. For retrospective studies, the weighted MD was −0.23 (95% CI: −0.31–−0.15), with pooled means of 27.43 and 34.02.

VAS-Back Pain

Seven studies provided enough data to obtain the final VAS scores, which were used as a measure of back pain for a duration of at least 12 months (Fig. 3B). There was no significant difference between the MI and OS group (Table 3).

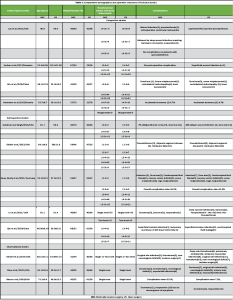

Complications

All 12 studies provided enough data to obtain complication rates. A total of 75 complications were observed in the MI group, whereas the OS group had 153 (Table 4). The most frequently observed complications, reported in multiple studies, included surgical site infection (7 cases in MI group versus 41 cases in OS group), accidental dural tear (12 cases in MI group versus 15 cases in OS group), hardware malpositioning (9 cases in MI group versus 11 cases in OS group), and revision surgery (13 cases in MI group versus 10 cases in OS group). There was no significant difference between the MI group and the OS group with respect to overall complications.

The acceptance of MI spinal surgery has risen due to the introduction of new concepts, improvements in surgical instruments, and the evolution of optical equipment. MI procedures have become more popular because to their smaller incisions, reduced iatrogenic soft-tissue injury, and faster functional recovery [26,27]. After doing a meta-analysis on the existing comparative studies, it was found that MI is linked to a considerable reduction in intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stays, and no deterioration in functional, pain, or complication outcomes compared to OS. This is the third review, following the analyses by Lu et al. [10] and Qin et al. [28], specifically focusing on the outcomes related to spondylolisthesis. Some of the studies included in this review examined patients with coexisting illnesses [17,23,24], which could have had an impact on functional and pain results [29]. Subsequent research indicates that these parameters will facilitate an enhanced understanding of post-operative functional and pain outcomes in both MI and OS. This review found no statistically significant difference in the long-term functional or pain outcomes between spondylolisthesis patients treated with MI or OS when comparing the ODI and VAS measurements. The aggregated findings of the meta-analysis align with other systematic reviews [8-11] that have investigated various degenerative lumbar conditions. There has been a significant reduction in intraoperative blood loss and hospital stay duration in MI. Comparable findings have been found in systematic reviews [30-33] that focus on lumbar disease in general. MI demonstrates reduced muscular atrophy and changes in blood circulation in comparison to OS. Smaller incisions and reduced retraction could expedite the recovery time. These are particularly beneficial for individuals with immune-related and hematologic problems, as they experience a decreased likelihood of infection and blood loss. The most significant conclusion of our meta-analysis is that there is no higher connection between complications and OS. Furthermore, our research indicates that the likelihood of surgical site infection is greatly diminished in patients who undergo MI compared to those who undergo OS (7 vs. 44). According to these data MI may offer a less intrusive option for treating spondylolisthesis, while yet achieving similar patient-rated outcomes and complication rates as in OS patients.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, it employed a thorough literature search method. Second, it strictly followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [34]. Finally, it utilized the GRADE system to examine high-quality evidence. We were able to conduct the third meta-analysis and systematic review comparing MI versus OS, specifically focusing on spondylolisthesis. Nevertheless, the findings of this research must be validated through substantial, multi-institutional prospective randomized controlled trials with thorough long-term monitoring. Until now, this evidence is one of the most compelling arguments for the therapeutic effectiveness of MI in the treatment of spondylolisthesis. A significant drawback of this study was the lack of information on the comparative outcomes of spinal fusion surgery for spondylolisthesis, specifically in cases of isthmic and higher-grade spondylolisthesis. Out of all the studies reviewed, only three [15-17] included outcomes specifically linked to isthmic spondylolisthesis. In addition, in two of these studies, the results for isthmic spondylolisthesis were mixed with those for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Wu et al. [16] found no noticeable distinction in the outcomes of degenerative and isthmic spondylolisthesis between the MI and OS groups. Moreover, the inclusion of studies using different surgical procedures (percutaneous, mini-open, and muscle splitting) may have led to a broader range of surgical outcomes for that group. This variation in the definition of MI could have potentially altered the findings of this meta-analysis. Due to the absence of randomized controlled trials in our investigation and the inclusion of lower-quality retrospective and prospective studies, there is a possibility of selection bias. There is significant variability in the outcomes among these research studies. Several factors, such as the subjective nature of most outcomes, the variation in experience and workload among surgeons, and the inherent diversity of surgical techniques such as TLIF, PLIF, and PLF, can be attributed to this.

This is the third systematic evaluation of the literature that specifically compares the outcomes of MI spinal fusion with OS for the treatment of Grade I and Grade II spondylolisthesis. When comparing OS to MI, it was shown that MI was associated with a reduced duration of hospitalization, a lower amount of blood loss after surgery, and comparable rates of complications, discomfort, and overall functional improvement. Subgroup analysis of both prospective and retrospective studies found that MI was associated with longer operating durations and improved functional results. However, the existing research only concentrates on cases of low and extremely low quality, and there are no randomized clinical studies that investigate the outcomes of treating spondylolisthesis simply with MI or OS spinal fusion. Subsequent research will authenticate the findings of this investigation.

MI spinal fusion offers shorter operative times and hospital stays compared to OS for treating spondylolisthesis, according to this study. While MI shows advantages in reducing surgical stress and post-operative recovery, there is no significant difference in functional or pain outcomes between the two approaches. Both MI and OS demonstrate similar complication rates. Although MI appears promising, further long-term, randomized studies are needed to confirm its sustained efficacy and safety in managing spondylolisthesis.

References

- 1.Li N, Scofield J, Mangham P, Cooper J, Sherman W, Kaye A. Spondylolisthesis. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2022;14:36917. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Noordeen S, Fleming C, Gokulakrishnan R, Sivanandan MH. The functional outcome of surgical management of spondylolisthesis with posterior stabilization and fusion. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:119-24. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Gagnet P, Kern K, Andrews K, Elgafy H, Ebraheim N. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: A review of the literature. J Orthop 2018;15:404-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Wang YX, Káplár Z, Deng M, Leung JC. Lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis epidemiology: A systematic review with a focus on gender-specific and age-specific prevalence. J Orthop Translat 2016;11:39-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Ponkilainen VT, Huttunen TT, Neva MH, Pekkanen L, Repo JP, Mattila VM. National trends in lumbar spine decompression and fusion surgery in Finland, 1997-2018. Acta Orthop 2021;92:199-203. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, et al. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015;386:569-624. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Trends in Operating Room Procedures in US Hospitals, 2001-2011 HCUP Statistical Brief #171. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Davin SA, Savage J, Thompson NR, Schuster A, Darnall BD. Transforming standard of care for spine surgery: Integration of an online single-session behavioral pain management class for perioperative optimization. Front Pain Res 2022;3:856252. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Stienen MN, Smoll NR, Hildebrandt G, Schaller K, Tessitore E, Gautschi OP. Constipation after thoraco-lumbar fusion surgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014;126:137-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Lu VM, Panagiotis K, Hannah EG, Brandon AM, Kevin P, Mohamad B. Minimally invasive surgery versus open surgery spinal fusion for spondylolisthesis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine 2017;42:E177-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res J 2014;14:135. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Lau D, Lee JG, Han SJ, Lu DC, Chou D. Complications and perioperative factors associated with learning the technique of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF). J Clinic Neurosci 2011;18:624-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Serban D, Calina N, Tender G. Standard versus minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: A prospective randomized study. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:7236970. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Wu AM, Hu ZC, Li XB, Feng ZH, Chen D, Xu H, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive and open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in the treatment of single segmental lumbar spondylolisthesis: Minimum two-year follow up. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:105. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Hartmann S, Lang A, Lener S, Abramovic A, Grassner L, Thomé C. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: A prospective, controlled observational study of short-term outcome. Neurosurg Rev 2022;45:3417-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Sulaiman WA, Singh M. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis grades 1-2: Patient-reported clinical outcomes and cost-utility analysis. Ochsner J 2014;14:32-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Dibble CF, Zhang JK, Greenberg JK, Javeed S, Khalifeh JM, Jain D, et al. Comparison of local and regional radiographic outcomes in minimally invasive and open TLIF: A propensity score-matched cohort. J Neurosurg Spine 2022;37:384-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Zawy Alsofy S, Nakamura M, Ewelt C, Kafchitsas K, Lewitz M, Schipmann S, et al. Retrospective comparison of minimally invasive and open monosegmental lumbar fusion, and impact of virtual reality on surgical planning and strategy. J Neurol Surg Part A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2021;82:399-409. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Le H, Anderson R, Phan E, Wick J, Barber J, Roberto R, et al. Clinical and radiographic comparison between open versus minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bilateral facetectomies. Global Spine J 2021;11:903-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Qin R, Wu T, Liu H, Zhou B, Zhou P, Zhang X. Minimally invasive versus traditional open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of low-grade degenerative spondylolisthesis: A retrospective study. Sci Rep 2020;10:21851. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.McGirt MJ, Parker SL, Mummaneni P, Knightly J, Pfortmiller D, Foley K, et al. Is the use of minimally invasive fusion technologies associated with improved outcomes after elective interbody lumbar fusion? Analysis of a nationwide prospective patient-reported outcomes registry. Spine J 2017;17:922-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Chan AK, Bydon M, Bisson EF, Glassman SD, Foley KT, Shaffrey CI, et al. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for grade I lumbar spondylolisthesis: 5-year follow-up from the prospective multicenter Quality Outcomes Database registry. Neurosurg Focus 2023;54:E2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Bisson EF, Mummaneni PV, Virk MS, Knightly J, Alvi MA, Goyal A, et al. Open versus minimally invasive decompression for low-grade spondylolisthesis: Analysis from the quality outcomes database. J Neurosurg Spine 2020;33:349-59. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Mobbs RJ, Sivabalan P, Li J. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open spinal fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar spine pathologies. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:829-35. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Badlani N, Yu E, Kreitz T, Khan S, Kurd MF. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF). Clin Spine Surg 2012;33:62-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 28.Qin R, Liu B, Zhou P, Yao Y, Hao J, Yang K, et al. Minimally invasive versus traditional open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of single-level spondylolisthesis grades 1 and 2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2019;122:180-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 29.Choma TJ, Schuster JM, Norvell DC, Dettori JR, Chutkan NB. Fusion versus nonoperative management for chronic low back pain: Do comorbid diseases or general health factors affect outcome? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:S87-95. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 30.Khan NR, Clark AJ, Lee SL, Venable GT, Rossi NB, Foley KT. Surgical outcomes for minimally invasive vs open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg 2015;77:847-74. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 31.Goldstein CL, Macwan K, Sundararajan K, Raja Rampersaud Y. Comparative outcomes of minimally invasive surgery for posterior lumbar fusion: A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1727-37. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 32.Sidhu GS, Henkelman E, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ, Hilibrand A, Greg Anderson D, et al. Minimally invasive versus open posterior lumbar interbody fusion: A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1792-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 33.Tian NF, Wu YS, Zhang XL, Xu HZ, Chi YL, Mao FM. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: A meta-analysis based on the current evidence. Eur Spine J 2013;22:1741-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Douglas G Altman; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PloS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [Google Scholar | PubMed]