Timely identification, accurate classification, and an individualized surgical approach are essential for achieving optimal outcomes in management of peri-prosthetic fractures in rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Dr. Rathina Easwar V Ra, Post Graduate, Department of Orthopaedics, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai-600044, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: rathina.easwar@gmail.com

Introduction: Periprosthetic fractures (PPFs) around the knee following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) present a significant challenge in orthopedic management, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). These fractures are influenced by factors such as bone stock quality, prosthetic status, polyethylene wear, and fracture reducibility. Proper classification and management strategies are essential to optimize outcomes and prevent complications.

Case Report: A 52-year-old female with RA sustained a right knee PPF following a trivial fall. Clinical and radiographic evaluation classified the fracture based on prosthetic stability and bone quality: • Type II fracture with a loose prosthesis requiring revision surgery. She underwent staged revision TKA including: 1. Definitive surgery with revision TKA and bone grafting. 2. Postoperative rehabilitation to restore function.

Conclusion: Management of PPFs in RA patients requires a comprehensive approach, including preoperative planning, prosthetic evaluation, osteoporosis management, and staged surgical intervention when necessary. This case highlights the importance of addressing osteoporosis alongside osteoarthritis in improving TKA outcomes. Further research is needed to refine treatment strategies for PPFs in RA patients.

Keywords: Periprosthetic fractures, total knee arthroplasty, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, revision total knee arthroplasty.

Periprosthetic fractures (PPFs) around the knee after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) represent a significant clinical challenge, especially in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This article explores the fundamental principles, treatment approaches, and overall outcomes for femoral and tibial PPFs in RA patients.

Using the classification system that incorporates prosthetic stability, bone quality, and fracture reducibility [1]:

- Type I: Intact bone stock with well-fixed prosthesis.

- IA: Non-displaced or easily reducible (treated conservatively)

- IB: Irreducible (requires reduction with internal fixation)

- Type II: Good bone stock with reducible fracture but loose or malpositioned components (requires revision arthroplasty)

- Type III: Compromised bone stock and loose/misaligned components (requires extensive revision surgery)

This classification aids in selecting appropriate treatment strategies and improving outcomes for PPFs in RA patients.

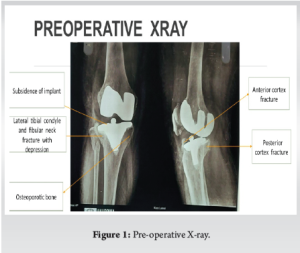

A 52-year-old female with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), who had undergone right total knee replacement 8 years ago, presented to the emergency department after a slip and fall at home, which resulted in difficulty bearing weight. On examination and radiological imaging, a periprosthetic fracture was identified in the right lateral tibial condyle with anterior and posterior cortex involvement (Fig. 1), and further characterized using CT imaging (Fig. 2). Implant loosening was noted, and damage to the polyethylene insert was present. Based on the discussed classification, this was categorized as a Type III PPF.

The patient had been asymptomatic prior to this event and was on long-term anti-rheumatoid treatment. Preoperative labs and infection markers were within normal limits. Once medically optimized, she was scheduled for staged right knee revision TKA.

She was on oral methotrexate pre-operatively, which was continued post-operatively without interruption.

Surgical Procedure

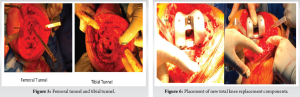

The patient was placed supine on a radiolucent table. A standard median parapatellar incision was used. The old implant was removed (Fig. 3 and 4), along with all fibrous tissue and residual bone cement. Both medial and lateral collateral ligaments were released. The area was thoroughly irrigated with pulse lavage.

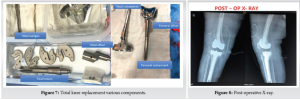

The revision surgery used a tibial wedge system with femoral augments, secured with gentamicin-impregnated cement (Fig. 5 and 6). Although a hinge system was planned, intraoperative findings allowed for the use of a non-hinged constrained prosthesis.

Post-operatively, the patient was started on teriparatide for 6 months to promote bone healing. A long knee brace was applied for 4 weeks. Weight bearing with a walker was initiated immediately, and early knee flexion (up to 30°) and quadriceps strengthening were included in the rehabilitation protocol. Knee flexion was gradually progressed, and upright sitting was allowed after 3 weeks. At the 6-week follow-up, the patient walked independently without assistance, and no extensor lag was observed (Fig. 7 and 8).

At the 1-year follow-up, the patient remained pain-free, fully weight-bearing, and exhibited no extensor lag or instability (Fig. 9 and 10).

PPFs after TKA are relatively rare but clinically significant. Risk factors include poor bone quality—especially from RA, osteoporosis, long-term corticosteroid use, and advanced age [2-17]. Additional contributors include femoral notching, osteolysis, stiff knees, and stress risers like screw holes. Neurologic conditions (e.g., Parkinson’s, epilepsy, ataxia, cerebral palsy) may also increase fracture risk. Although no definitive link has been established between component malalignment and periprosthetic fractures, tibial varus malalignment may contribute to tibial PPFs [18-25]. In this patient, a Type III PPF was caused by a minor fall. Imaging confirmed fracture of the lateral tibial condyle and anterior/posterior cortices with polyethylene wear and component loosening (Fig. 1–4). Prompt preoperative work-up ruled out infection and allowed timely surgery. The Vancouver system classifies this as complex and necessitating revision (Fig. 6). Surgical management addressed implant replacement, polyethylene wear, and fracture stabilization. Early mobilization and structured rehab (Fig. 6-8) were critical to the patient’s recovery. The patient had a history of RA and methotrexate use, both of which impact bone density and healing. Hence, teriparatide therapy was initiated. At one year, radiological follow-up confirmed stable components and full recovery (Fig. 9 and 10). This case reinforces the importance of infection screening, prosthesis evaluation, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation. As TKA rates rise, so will PPFs, especially in immunosuppressed or osteoporotic populations. Continued improvement in implants, techniques, and post-op care are vital for managing such complex cases.

The case of this 52-year-old female demonstrates the complexities of managing a type III PPF, which required revision surgery following trauma. Timely identification, accurate classification, and an individualized surgical approach are essential for achieving optimal outcomes in such cases. Revision TKA can restore function and alleviate pain, but it is crucial to ensure comprehensive postoperative care and rehabilitation to minimize complications and ensure long-term recovery.

The increasing prevalence of TKA in younger and more active patients suggests that the incidence of PPFs will likely continue to rise. RA patients are 3.85 times likely to undergo TKA compared to general population and thus revision TKA rates also increase. This calls for ongoing improvements in surgical techniques, better strategies for managing complex fractures, and more focused research into long-term outcomes for these patients.

References

- 1.Kim KI, Egol KA, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic fractures after total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;446:167-75. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Althausen PL, Lee MA, Finkemeier CG, Meehan JP, Rodrigo JJ. Operative stabilization of supracondylar femur fractures above total knee arthroplasty: A comparison of four treatment methods. J Arthroplasty 2003;18:834-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Berry DJ. Periprosthetic fractures after major joint replacement. Epidemiology: Hip and knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1999;30:183-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Bezwada HP, Neubauer P, Baker J, Israelite CL, Johanson NA. Periprosthetic supracondylar femur fractures following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2004;19:453-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Cain PR, Rubash HE, Wissinger HA, McClain EJ. Periprosthetic femoral fractures following total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;208:205-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Chen F, Mont MA, Bachner RS. Management of ipsilateral supracondylar femur fractures following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1994;9:521-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Cordeiro EN, Costa RC, Carazzato JG, Silva Jdos S. Periprosthetic fractures in patients with total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;252:182-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Culp RW, Schmidt RG, Hanks G, Mak A, Esterhai JL Jr., Heppenstall RB. Supracondylar fracture of the femur following prosthetic knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;222:212-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Dorr LD. Fractures following total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics 1997;20:848-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Egol KA, Kubiak EN, Fulkerson E, Kummer FJ, Koval KJ. Biomechanics of locked plates and screws. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18:488-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Periprosthetic fractures adjacent to total knee implants: Treatment and clinical results. Instr Course Lect 1998;47:437-48. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Felix NA, Stuart MJ, Hanssen AD. Periprosthetic fractures of the tibia associated with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997;345:113-24. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE 3rd, Sobel M. The results of treatment of supracondylar fracture above total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1990;5:267-76. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Ghazavi MT, Stockley I, Yee G, Davis A, Gross AE. Reconstruction of massive bone defects with allograft in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:17-25. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Hayakawa K, Nakagawa K, Ando K, Ohashi H. Ender nailing for supracondylar fracture of the femur after total knee arthroplasty: Five case reports. J Arthroplasty 2003;18:946-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Healy WL, Siliski JM, Incavo SJ. Operative treatment of distal femoral fractures proximal to total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:27-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Inglis AE, Walker PS. Revision of failed knee replacements using fixed-axis hinges. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73:757-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Keenan J, Chakrabarty G, Newman JH. Treatment of supracondylar femoral fracture above total knee replacement by custom made hinged prosthesis. Knee 2000;7:165-70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Kraay MJ, Goldberg VM, Figgie MP, Figgie HE 3rd. Distal femoral replacement with allograft/prosthetic reconstruction for treatment of supracondylar fractures in patients with total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1992;7:7-16. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Kregor PJ, Hughes JL, Cole PA. Fixation of distal femoral fractures above total knee arthroplasty utilizing the less invasive stabilization system (L.I.S.S.). Injury 2001;32 (Suppl 3):SC64-75. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Lesh ML, Schneider DJ, Deol G, Davis B, Jacobs CR, Pellegrini VD Jr. The consequences of anterior femoral notching in total knee arthroplasty. A biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82:1096-101. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Lombardi AV Jr., Mallory TH, Waterman RA, Eberle RW. Intercondylar distal femoral fracture. An unreported complication of posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1995;10:643-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Influence of positioning of prosthesis in total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:77-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Maniar RN, Umlas ME, Rodriguez JA, Ranawat CS. Supracondylar femoral fracture above a PFC posterior cruciate-substituting total knee arthroplasty treated with supracondylar nailing. A unique technical problem. J Arthroplasty 1996;11:637-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.McLaren AC, Dupont JA, Schroeber DC. Open reduction internal fixation of supracondylar fractures above total knee arthroplasties using the intramedullary supracondylar rod. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994;302:194-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]