Pin site fracture can be avoided with appropriate placement of tracking pins.

Dr. Yong-Chan Ha, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seoul Bumin Hospital, Seoul 07590, South Korea. E-mail: hayongch@naver.com

Introduction: With the increasing use of robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty (RATKA), pin-related complications are uncommon, but can be distressing to both the surgeon and patient. We encountered two cases of tracking pin-related distal femoral and proximal tibial fractures and treated them surgically.

Case Report: Two patients developed fractures in the postoperative period following RATKA. A 67-year-old female presented with a minimally displaced tibial fracture, which was treated with open reduction and internal fixation using a narrow plate. A 69-year-old female developed a minimally displaced femoral fracture and underwent internal fixation with a broad plate.

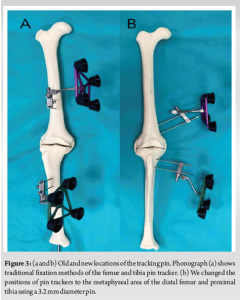

Conclusion: At the latest follow-up, the fractures healed completely. After changing the position of the tracking pin from the diaphysis of the femur and tibia to the metaphyseal area of the distal femur and proximal tibia using a 3.2 mm diameter pin, we have not yet encountered any more pin site fractures.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, robotic-assisted arthroplasty, pin tracker, tracking pin, complication.

Robot-assisted total knee arthroplasty (RATKA) was introduced to improve limb alignment, component positioning, and soft-tissue balancing [1]. Over the past decade, RATKA use has increased exponentially worldwide. This requires the placement of femoral and tibial pins fixed rigidly to the bone for the attachment of tracker arrays. Although uncommon, this can lead to pin-related complications such as pin site fracture, pin breakage, infection, delayed wound healing, persistent wound discharge, and neurovascular injuries. The incidence of pin site fractures has been reported to range from 0.06% to 4.8% and mostly occurs within the first 3 months postoperatively [2]. There is limited knowledge regarding the ideal location, size, and direction for the placement of femoral and tibial pins as measures to avoid pin-related complications. Here, we report two cases of RATKA performed in two patients with osteoarthritis (OA) who had pin-related complications and their management. We also suggest a surgical technique to minimize pin site-related complications.

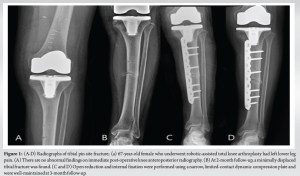

A 67-year-old female presented with bilateral knee pain for the past 4 years due to severe OA with a varus deformity. She had difficulty walking and climbing stairs because of the pain. The patient showed no improvement with conservative treatment or injections, and her activities of daily living were deteriorating. Her weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) were 47 kg, 150 cm, and 20.8, respectively. She underwent staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty using the CUVIS-Joint Robotic System (CUREXO Inc.). Four 3.2 mm diameter pins were used to place tracker arrays with two pins each for the femoral and tibial diaphysis. For the tibia, the first pin was placed 10 cm below the joint line, perpendicular to the anteromedial surface, and the second pin was placed through the drill guide provided with the system. Both were placed with separate stab incisions. For the femur, the first pin was placed 10 cm above the joint line, and the second pin was placed through the drill guide with a separate stab incision. Post-operative radiographs were normal with good alignment of the components. In the post-operative period, she was allowed immediate weight-bearing as tolerated and underwent normal physiotherapy as per our institutional protocol without the need for aggressive rehabilitation or manipulation. The patient was discharged without complications. At the 2-month follow-up, she reported aggravated pain in the left lower leg. Physical examination revealed swelling and tenderness in the mid-third of the left lower leg, with abnormal mobility and crepitus. Radiography revealed a transverse fracture of the left tibia at the distal pin tract site. The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation with a narrow, limited contact dynamic compression plate (LC-DCP). During the post-operative period, the patient was kept non-weight-bearing for 6 weeks with quadriceps strengthening and knee range of motion (ROM) exercises. Partial weight-bearing was started after 6 weeks, with follow-up radiographs showing the progress of fracture union. After 3 months, bony union was identified, and the patient resumed her activities. The patient had full knee ROM at the final follow-up (Fig. 1a, b, c, d).

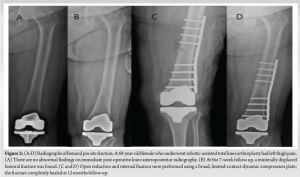

A 69-year-old female presented with bilateral knee pain for the past 3 years due to severe OA. Her weight, height, and BMI were 70 kg, 153 cm, and 29.9, respectively. Physical examination revealed diffuse swelling of both knees with crepitus, joint line tenderness, and limited ROM. The patient underwent staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty using a Mako robotic system (Stryker Inc.). Four 3.2 mm diameter pins were used to place tracker arrays with two pins each for the femur and tibia. For the tibia, the first pin was placed 10 cm below the joint line, perpendicular to the anteromedial surface, and the second pin was placed through the drill guide provided with the system. Both were placed with separate stab incisions. For the femur, the first pin was placed 13 cm above the joint line. The patient was discharged without complications. Seven weeks after the index surgery, she reported aggravated pain in the left thigh and difficulty walking. Radiography revealed a transverse fracture of the left femoral shaft at the distal pin tract site. The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation with a broad LC-DCP. She was kept non-weight-bearing for 6 weeks with quadriceps strengthening and knee ROM exercises. Partial weight-bearing was started after 6 weeks, with follow-up radiographs showing the progress of fracture union. After 6 months, bony union of the fracture site was identified, and the patient resumed her activities. The patient had full knee ROM at the final follow-up (Fig. 2a, b, c, d).

Although RATKA has been introduced to improve limb alignment and component positioning, there is a surgical risk of pin-related complications due to mechanical weakening of the bone with the placement of pins for tracker array attachment. We encountered two cases of femoral shaft and tibial shaft fractures related to stress fractures of the pin trackers. All patients underwent additional surgery, and fractures were healed at a minimum 12-month follow-up. Subsequently, we changed the placement of the pin from the diaphysis to the metaphysis or meta-diaphyseal area. Pin site-related complications during RATKA are uncommon but can be distressing to both the surgeon and patient. Several previous studies have reported pin-related complications during navigated total knee arthroplasty. Brooks et al. showed that drilling holes through the bone significantly reduces its bending and torsional strength [3]. Jung et al. reported that thermal necrosis of bone during pin drilling may lead to periprosthetic fracture and that the pin tract site may persist even after 12 months due to delayed cortical remodeling [4]. Demographic characteristics of patients, implants, and surgical factors are possible causes of tracking pin-related complications. First, patient factors include female sex, old age, obesity, osteoporosis, activity level, corticosteroid use, diabetes, cardiac disease, and any disorder that may increase the risk of falls [5,6]. Second, the implant factors include small- or large-diameter pins, posterior stabilized versus cruciate-retaining implant with added stress riser from the box cut, and removal of previous hardware [7]. Finally, surgical factors include faulty placement of pins (transcortical, misdirection, and multiple attempts), notching of the anterior femur, instability, malalignment of components, and improper gap balancing with excessive tightness. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies. In this study, the mal-positioned tracking pin site acted as a stress riser and led to stress fractures within 3 months of surgery. Fortunately, both fractures were successfully healed after plate fixation. To prevent pin site-related complications, the location and size of the pins used may be important. Although knowledge is limited regarding the ideal location, size, and direction for pin placement, some authors prefer metaphysis over diaphysis and small-diameter pins over large-diameter pins [8,9]. Yun et al. recommended metaphyseal placement of pins because the bone in this region is more robust to bending and torsional stresses than that in the diaphyseal region [10]. Beldame et al. reported that almost all periprosthetic fractures in their series occurred at the diaphyseal pin tract site [9]. Hoke et al. reported pin-related diaphyseal stress fracture of the tibia in three of 220 patients and recommended the use of small-diameter self-drilling and self-tapping metaphyseal pins, preferably in different planes [11]. Our recommended technique for minimizing pin tracker-related fractures is the placement of the first tibial pin 2 cm medial to the tibial tuberosity within the wound perpendicular to the tibial surface, just touching the opposite cortex. The second pin is inserted through the drill guide with a separate stab incision in the same direction. On the femoral side, the first pin is placed within the wound, 2 cm above the medial epicondyle, from the anteromedial to the posterolateral direction to a depth of 4 cm, and the second pin is placed through the drill guide with a separate stab incision in the same direction (Fig. 3a and b). We prefer a 3.2 mm diameter for all four pins. With these modifications, we have not encountered any pin-related periprosthetic fractures in our practice.

This case report highlights the potential for pin-related complications, specifically stress fractures, following RATKA. While uncommon, these complications can significantly impact patient recovery and quality of life. Careful consideration of pin placement, including location (metaphyseal preferred), size, and direction, is crucial to minimize the risk of such events. Our modified technique, involving specific pin placement within the metaphyseal region, has shown promising results in our practice in preventing pin-related complications. Further research with larger sample sizes is warranted to validate these findings and establish optimal pin placement strategies for enhanced patient safety and improved outcomes in RATKA.

RATKA can improve surgical outcomes, but pin-related complications, such as stress fractures at the pin insertion sites, remain a rare but significant risk. To minimize these complications, we recommend placing pins in the more robust metaphyseal region rather than the diaphysis, using smaller 3.2 mm pins, and carefully positioning them to avoid stress risers. Our modified technique has shown promising results, with no further pin-related fractures, suggesting that careful pin placement can reduce such risks and improve patient outcomes in RATKA.

References

- 1.Zhang J, Ndou WS, Ng N, Gaston P, Simpson PM, Macpherson GJ, et al. Robotic-arm assisted total knee arthroplasty is associated with improved accuracy and patient reported outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022;30:2677-95. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Blue M, Douthit C, Dennison J, Caroom C, Jenkins M. Periprosthetic fracture through a unicortical tracking pin site after computer navigated total knee replacement. Case Rep Orthop 2018;2018:2381406. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Brooks DB, Burstein AH, Frankel VH. The biomechanics of torsional fractures. The stress concentration effect of a drill hole. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:507-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Jung KA, Lee SC, Ahn NK, Song MB, Nam CH, Shon OJ. Delayed femoral fracture through a tracker pin site after navigated total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:505.e9-505.e11. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Meek RM, Norwood T, Smith R, Brenkel IJ, Howie CR. The risk of peri-prosthetic fracture after primary and revision total hip and knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:96-101. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Singh JA, Jensen M, Lewallen D. Predictors of periprosthetic fracture after total knee replacement: An analysis of 21,723 cases. Acta Orthop 2013;84:170-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Alden KJ, Duncan WH, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW, Haidukewych GJ. Intraoperative fracture during primary total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:90-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Bonutti P, Dethmers D, Stiehl JB. Case report: Femoral shaft fracture resulting from femoral tracker placement in navigated TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:1499-502. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Beldame J, Boisrenoult P, Beaufils P. Pin track induced fractures around computer-assisted TKA. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96:249-55. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Yun AG, Qutami M, Pasko KB. Do bicortical diaphyseal array pins create the risk of periprosthetic fracture in robotic-assisted knee arthroplasties? Arthroplasty 2021;3:25. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Hoke D, Jafari SM, Orozco F, Ong A. Tibial shaft stress fractures resulting from placement of navigation tracker pins. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:504.e5-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]