Early diagnosis and appropriate fixation of pediatric capitellum fractures using bio-absorbable K-wires can lead to successful recovery and prevent complications.

Dr. Fawaz Mohammed Manu, Department of Orthopaedics, Parco Hospital And Research Center, Vadakara, NH Bypass, Kozhikode, Vatakara - 673 106, Kerala, India. E-mail: pvfawaz@gmail.com

Introduction: Pediatric capitellum fractures are rare, accounting for <1% of elbow fractures in children. They are typically caused by axial loading on an outstretched arm. Due to the high cartilaginous composition of the pediatric elbow, these fractures are often missed in radiographic diagnosis. Proper diagnosis using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is essential for effective treatment planning.

Case Report: A 14-year-old female sustained a left elbow injury following a fall while playing. Clinical and radiological evaluations confirmed a displaced Hahn–Steinthal fracture of the capitellum. Open reduction and internal fixation using bio-absorbable K-wires were performed. Postoperatively, an above-elbow cast was applied for 4 weeks. At 10 weeks, the patient had achieved a full range of motion, and radiographic assessment confirmed fracture union.

Conclusion: Pediatric capitellum fractures, though rare, can lead to significant morbidity if not diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. The use of bio-absorbable K-wires offers an effective fixation method, eliminating the need for a second surgery for implant removal. Early intervention, proper radiological assessment, and surgical management result in excellent functional outcomes with minimal complications.

Keywords: Paediatric, Elbow Fractures Capitellar, K-wires

Isolated capitellum fractures account for <1% of elbow fractures in children [1]. These fractures are generated by an axial load towards the humeral paddle with an elbow in extension or semiflexion, as in a fall on the outstretched arm [2]. Depending on the flexion or extension of the elbow at injury, the fracture fragment can be anterior or posterior. These fractures can also be generated by a posterolateral elbow dislocation or subluxation due to the impact of the radial head and coronoid against the capitellum [3]. Even though in many cases they are isolated, they can also be associated with other injuries of the lateral column, such as radial head or neck fractures, lateral condyle fractures, lateral collateral ligament complex avulsion, and medial condyle and olecranon fractures [4]. There are two main classifications, Bryan Morrey classification and Dubberley classification, in which they are usually classified according to Morrey classification [5], in which type-1 is a common hahn-steinthal fracture is an isolated fracture of the capitellum, characterized by a single fracture fragment including both the chondral and subchondral component of the capitellum, eventually extended to the lateral trochlear ridge. Type 2, the Kocher-Lorenz fracture, is a thin articular cartilage fragment of the capitellum. Type 3, also called Broberg–Morrey fracture, has the same extension as Type 1 but is comminuted. McKee added a fourth type to the Bryan–Morrey classification that extends up to the trochlear groove [6]. Dubberley classified capitellar fractures into three types, differentiated by the extension in the trochlea, each one distinguished in type A and B, according to a more anterior or posterior involvement of the capitellum on the sagittal plane [7]. The diagnosis of capitellar fracture is often missed or delayed due to the anatomical feature of the elbow due to which they have been grouped among the so-called TRASH injuries. “The Radiographic Appearance Seemed Harmless” [8], including also osteochondral fractures of the radial head and lateral condyle, incarcerated medial epicondylar and unossified medial condylar fractures, transphyseal separations of the distal humerus, and Monteggia lesions. The pediatric elbow anatomy is characterized by six ossification centers, merged in radio-transparent physes, which fuse during adolescence in sequential order, beginning from the capitellum, trochlea, and olecranon around the age of 14 [9]. Consequently, any injury before the fusion of the ossification centers can cause chondral or osteochondral fragments that can be missed on radiographs, especially if small in size. In clinical practice, capitellar fracture diagnosis depends on clinical symptoms rather than radiographic diagnosis, as a high cartilaginous component of the pediatric elbow, making impossible a direct radiographic diagnosis of small chondral fragments. Radiographs would rather show a double contour sign when the fracture involves the subchondral bone or just a fat pad sign in the case of a small chondral fragment [10]. Clinicians should further investigate when clinical symptoms of swelling and tenderness are present around the elbow. Limitation of motion is not only associated with pain but also with mechanical blockage of the elbow due to the interposition of the fragment. In these cases, investigations are usually pursued with a computed tomography scan (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the elbow to characterize the fracture pattern and plan the surgery. The surgical approach and osteosynthesis or fragment excision are planned based on the imaging, leaving margins for the intraoperative adaptation of the strategy [11].

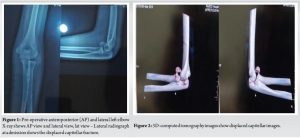

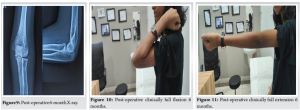

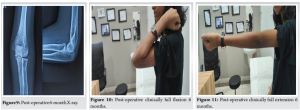

A female patient of age 14 years had a self-fall at home while playing and sustained an injury to the left elbow, following which she had complaints of pain, swelling, and limitation of movements in the left elbow. The elbow was then temporarily immobilized in a soft splint, an X-ray (Fig. 1) was taken, and a later CT scan (Fig. 2) was taken for proper planning. The CT scan of the elbow showed a shear fracture of the capitellum involving the lateral trochlear ridge, a Hahn–Steinthal fracture, with proximal and medial displacement. The surgery was scheduled for the following day. The patient was hospitalized, and surgery was scheduled for the following day. The fracture was approached by an anterolateral approach, reduced and fixed by two bio-absorbable K-wires. The elbow was immobilized in an above-elbow cast for 4 weeks. At 10 post-operative weeks, the patient achieved a full range of motion and was allowed to gradually begin sportive activities. The radiographs showed the union of the fracture. The follow-up is still ongoing, with a planned consultation and 6 and 12 post-operative months.

Surgical steps

Step 1

Patient in a supine position, in general anesthesia, by direct lateral approach, the capitellar fracture site was visualized, and the reduction was attained and stabilized with 2 K-wires (Fig. 3).

Step 2

To insert a graded K-wire perpendicular to the fracture, measure the distance inserted to the bone by checking the grading in the graded K-wire (Figs. 4,5).

Step 3

Marking the length of the K-wire needed onto the bio-absorbable K-wire and making a blunt cut in the bio-absorbable K-wire (Fig. 5).

Step 4

Inserting the bio-absorbable K-wire in the previous graded K-wire tract after placing it in a cylindrical sleeve, then malleting it in a blunt cut area so that it gets flattened and stays at the site (Fig. 6,7).

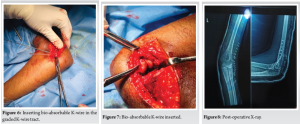

Post-operative

Postoperatively, a long arm cast was applied for 1 month. Daily routine and functional exercises were started once the cast was removed. Patients were evaluated at intervals of 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery with clinical and radiological results assessment (Fig. 8,9).

The capitellar fracture usually showed a bimodal distribution, with the first peak in childhood (<10 years) [12,13] and the second peak, the most representative, in pre-adolescents and adolescents [14,15]. The most frequent associated injury was the ipsilateral elbow dislocation, followed by the involvement of the medial or lateral condyle or an olecranon or radial head fracture [16]. Due to clinical misdiagnosis and low occurrence of capitellar fractures in the pediatric population, they should be treated early as they limit the child’s elbow function and life. Delay in diagnosis will increase the probability of complications in children [17]. Most of the cases with an early diagnosis were managed with open reduction and internal fixation. This was probably related to the fact that the fractures characterized by a remarkable displacement were promptly diagnosed on conventional radiographs. The fractures whose diagnosis was delayed were susceptible to all treatment strategies, from a conservative attitude when the clinical status allowed, rather than fragment excision or fixation [18]. The radiographs are the baseline investigation for diagnosis, accompanied by a clinical diagnosis. The use of CT and MRI has improved the diagnosis of capitellar fractures, allowing us to visualize them early and plan the treatment. The availability of CT and MRI within the first weeks from the injury allowed setting a threshold of 2 weeks between the acute and delayed diagnosis [19]. The no-displaced Capitellar fracture can be treated conservatively with the above elbow cast [20]. Surgical indication lies in a symptomatic displaced fracture of the capitellum, while the most important factor for surgical indication includes mechanical blockage to the elbow range of motion. The most used surgical methods are screw and Kirschner wire fixation; K-wires were usually fixed percutaneously, allowing the removal between 3–8 post-operative weeks [21]. The headless screws have taken the place of cancellous screws, not requiring another surgery for hardware removal and being well tolerated in most cases. In the case of small fragments generating a mechanical blockage in the joint, whose size does not allow any fixation, these fractures are accessible for excision by an open or even arthroscopic approach. In this case, we opted for bio-abosarble screws as the fracture fragment is small and not fully accessible for screw fixation since it is causing mechanical blockage open reduction and stabilization with bio-abosarble K-wire was done, as it would not require any further procedure afterward. The treatment has allowed good clinical and radiological outcomes in many cases. The post-operative complications include limitation of movements, especially extension, persistent pain, and even blockage. The limitation of the elbow can be due to soft tissue contracture, in which arthrolysis is done when a functional arc of motion is affected. On the other hand, pain and blockage can be due to radiocapitellar osteoarthritis, capitellar necrosis, and, in rare cases, loose fragments or cartilage defects, requiring surgical management [22]. radiocapitellar osteoarthritis and capitellar necrosis in delayed cases seem to be equally distributed (Fig. 10,11).

Pediatric capitellum fractures, though rare, can lead to significant morbidity if not diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. The use of bio-absorbable K-wires offers an effective fixation method, eliminating the need for a second surgery for implant removal. Early intervention, proper radiological assessment, and surgical management result in excellent functional outcomes with minimal complications.

Early diagnosis and appropriate surgical intervention in pediatric capitellum fractures are crucial for achieving optimal recovery. The use of bio-absorbable K-wires is a promising method to ensure stable fixation while avoiding the necessity for hardware removal, thereby reducing patient morbidity.

References

- 1.Marion J, Faysse R. Fracture du capitellum. Rev Chir Orthop 1962;48:484-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Faber KJ. Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus: The capitellum and trochlea. Hand Clin 2004;20:455-64. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Fram BR, Seigerman DA, Ilyas AM. Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus: A review of diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Hand (N Y) 2021;16:577-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Cottalorda J, Bourelle S. The often-missed Kocher-Lorenz elbow fracture. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009;95:547-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Draenert K, Willenegger H. Fractures of the distal humerus of children and the distal tibia with involvement of the epiphyseal groove. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 1985;123:522-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Bryan R, Morrey B. Fractures of the distal humerus. In: Morrey B, editor. The Elbow and its Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1985. p. 325-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Dubberley JH, Faber KI, MacDermid JC, Patterson SD, King GJ. Outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of capitellar and trochlear fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:46-54. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Waters PM, Beaty J, Kasser J. Elbow “tRASH” (the radiographic appearance seemed harmless) lesions. J Pediatr Orthop 2010;30 Suppl 2:S77-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Jauregui JJ, Abzug JM. Anatomy and development of the pediatric elbow. In: Abzug JM, Herman MJ, Kozin S, editors. Pediatric Elbow Fractures. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018. p. 3-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Lee JJ, Lawton JN. Coronal shear fractures of the distal humerus. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:2412-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Pilotto JM, Valisena S, De Marco G, Vazquez O, De Rosa V, Mendoza Sagaon M, et al. Shear fractures of the capitellum in children: A case report and narrative review. Front Surg 2024;11:1407577. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Fuad M, Elmhiregh A, Motazedian A, Bakdach M. Capitellar fracture with bony avulsion of the lateral collateral ligament in a child: Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017;36:103-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Pradhan BB, Bhasin D, Krom W. Capitellar fracture in a child: The value of an oblique radiograph. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:635-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Cao C, Xing H, Cao F, Du Z, Wang G, Wang X. Three-dimensional printing designed customized plate in the treatment of coronal fracture of distal humerus in teenager: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102:e32507. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Simanovski N, Horowitz RS, Goldman V, Sharabati T, Lamdan R, Zaidman M. Capitellum and capitellar-trochlear shear injury in children. J Orthop Trauma 2023;37:e68-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Bilić R, Kolundžić R, Antičević D. Absorbable implants in surgical correction of a capitellar malunion in an 11-year-old: A case report. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:66-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Nagda TV, Vaidya SV, Pinto DA. Chondral shear fracture of the capitellum in adolescents-a report of two late diagnosed cases and a review of literature. Indian J Orthop 2020;54 Suppl 2:403-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Frank JM, Saltzman BM, Garbis N, Cohen MS. Articular shear injuries of the capitellum in adolescents. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016;25:1485-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Kraus R, Lieber J, Schwerk P, Rüther H, Tüshaus L, Karvouniaris N, et al. Incidence, treatment techniques, and results of distal humeral coronal shear fractures in children and adolescents-a multicenter study of the German section of pediatric traumatology (SKT). Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2023;50:2673-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Murthy PG, Vuillermin C, Naqvi MN, Waters PM, Bae DS. Capitellar fractures in children and adolescents: Classification and early results of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:1282-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Papamerkouriou YM, Tsoumpos P, Tagaris G, Christodoulou G. Type IV capitellum fractures in children. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e229957. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Onay T, Gümüştaş SA, Baykan SE, Akgülle AH, Erol B, Irgit KS. Mid-term and long-term functional and radiographic results of 13 surgically treated adolescent capitellum fractures. J Ped Orthop 2018;38:e424-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]