In Frozen shoulder, ultrasound-guided intra-articular steroid offers better short- to mid-term pain relief and shoulder function than electrotherapy, enabling faster recovery and improved quality of life.

Dr. Vejaya Kumar, Department of Orthopaedics, Vinayaka Mission’s Medical College and Hospital, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (Deemed to be University), Karaikal, India. E-mail: dr.vejay87@gmail.com

Background: Frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) is a disabling condition marked by pain and restricted range of motion (ROM). This study compares the effectiveness of electrotherapy (ET) and ultrasound-guided intra-articular steroid injections (UG-IASI), two common non-operative treatments.

Materials and Methods: In this prospective, randomized trial, 60 patients with unilateral Frozen shoulder were assigned to either ET (n = 30) or UG-IASI (n = 30). Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 1, 3, and 6 months, and 1 year using the shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) and ROM measurements. Statistical analyses included mixed-effects models and subgroup analysis for diabetes.

Results: UG-IASI resulted in significantly greater SPADI and ROM improvements than ET at 1, 3, and 6 months (P < 0.05). By 1 year, the difference was no longer significant. UG-IASI showed notable gains in abduction and flexion. Diabetic patients experienced reduced improvements across both groups.

Conclusion: UG-IASI provides superior early and mid-term outcomes in pain relief and shoulder function compared to ET. While long-term differences narrow, early intervention with UG-IASI supports faster recovery. A tailored approach, considering comorbidities and patient needs, is recommended for optimal care.

Keywords: Frozen shoulder, electrotherapy, steroid injection, adhesive capsulitis, shoulder pain and disability index, range of motion

Frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis or periarthritis, is a painful and progressively disabling condition marked by significant restriction in both active and passive range of motion (ROM) [1]. It typically affects individuals aged 40–60 years, with a prevalence of 2%–5% in the general population, and up to 20% among those with diabetes mellitus, indicating a possible metabolic contribution to its pathogenesis. The condition evolves through distinct phases: Initial pain, progressive stiffness due to capsular fibrosis, and a gradual resolution that may take up to 3 years [2]. During this course, patients often experience impaired daily functioning, reduced productivity, and increased healthcare utilization. Despite a well-characterized natural history, optimal management strategies for frozen shoulder remain a subject of debate [3,4]. Treatment approaches range from conservative methods, such as physiotherapy and analgesics to interventional options, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injections and surgical release in refractory cases [5,6]. Electrotherapy (ET) using interferential therapy (IFT), short wave diathermy (SWD), and ultrasound therapy (UST) is commonly used in physiotherapy to reduce pain and maintain joint mobility. In contrast, intra-articular steroid injection (IASI), particularly when guided by ultrasound (UG-IASI), offer targeted anti-inflammatory effects and are gaining favor for their potential to accelerate symptom relief [7,8].

UG-IASI improves the accuracy and safety of drug delivery by allowing real-time visualization of joint structures, reducing risks, such as tendon or vascular injury [9]. While both ET and IASI are clinically effective, direct comparisons are limited and often inconclusive, leading to uncertainty about the optimal first-line treatment, especially in patients with comorbidities, such as diabetes [10,11]. Existing studies vary widely in their physiotherapy protocols, follow-up durations, and outcome measures, making comparisons difficult and limiting clinical applicability [12]. Moreover, many investigations focus only on short-term results, overlooking the chronic nature of the condition. Given the variability in patient responses, especially among diabetics, a more nuanced, evidence-based understanding of treatment outcomes is essential [13,14]. This study was designed to directly compare the clinical efficacy of ET and UG-IASI in frozen shoulder through a prospective, randomized trial. Outcome evaluation included both objective (ROM) and subjective shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) measures over a 1-year follow-up. The impact of diabetes mellitus on treatment response was also assessed, offering insights into personalized approaches for managing this common and often challenging musculoskeletal disorder.

Study design and setting

This prospective, randomized, parallel-group clinical study was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedics, Vinayaka Mission’s Medical College and Hospital, Karaikal, India, between April 2022 and April 2024. Ethical committee approval was obtained (Ref: VMMCH/IEC/2022/04), and all participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

Adults aged 18–70 with unilateral shoulder pain and stiffness for at least 1 month were included. Clinical diagnosis criteria required restricted passive ROM in at least two planes, with external rotation (ER) ≤50% of the opposite shoulder.

Inclusion criteria

- Age between 18 and 70 years

- Clinical diagnosis of frozen shoulder

- Unilateral involvement

- Restricted passive ER ≤50%

- Willingness to participate and provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

- Previous shoulder surgery or fractures

- Full-thickness rotator cuff tears (confirmed clinically and by imaging)

- Radiographic evidence of glenohumeral osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis or other systemic inflammatory conditions

- Contraindications to steroid injection (local infection, uncontrolled diabetes)

- Inability to comply with the study protocol.

Sample size calculation

Based on a prior study by Foula et al., a mean difference of 15 points (standard deviation ± 20) in SPADI scores between treatment groups at 6 months was anticipated. To detect this difference with 80% power and a 5% significance level, a minimum sample size of 27 patients per group was calculated using G*Power 3.1. Accounting for an expected dropout rate of 10%, 30 participants were recruited per group, totaling 60 patients. [11].

Randomization and allocation

Participants were randomized into two groups (ET [n = 30] and UG-IASI, n = 30) – using a computer-generated sequence with allocation concealment through sealed envelopes. Due to the nature of interventions, blinding of patients and clinicians was not possible; however, outcome assessments were performed by a blinded independent evaluator. Although the intervention could not be blinded for practical reasons, our study employed blinded outcome assessors, reducing the risk of detection bias and increasing internal validity.

Interventions

ET group

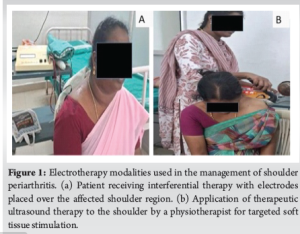

The ET group received structured sessions, including IFT (15–20 min), SWD (15–20 min), and UST (5–8 min), administered by a licensed physiotherapist (Fig. 1).

Sessions were tapered from 3/week to once weekly over 3–6 months. Present clinical guidelines and rehabilitation practices often recommend a multimodal therapy approach rather than relying on a single treatment, especially for musculoskeletal conditions. All patients also followed a prescribed home-based exercise program to maintain shoulder mobility.

Sessions were tapered from 3/week to once weekly over 3–6 months. Present clinical guidelines and rehabilitation practices often recommend a multimodal therapy approach rather than relying on a single treatment, especially for musculoskeletal conditions. All patients also followed a prescribed home-based exercise program to maintain shoulder mobility.

IASI group

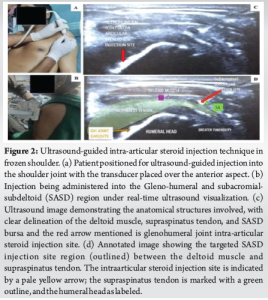

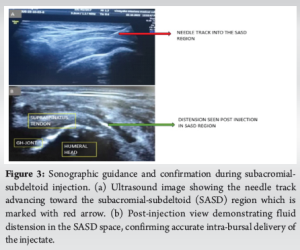

The steroid group received a single UG-IASI of 40 mg triamcinolone (1 mL) with 2% lignocaine (3 mL) each into the Gleno-Humeral joint and Subacromial-Subdeltoid (SASD) bursa using a high-frequency transducer (Figs. 2 and 3). Ice was applied post-injection and ROM exercises were initiated within 24–48 h based on patient tolerance. As there is no generally accepted protocol, we have restricted the use of steroid injection to a single shot because there may be degenerative changes or metabolic and endocrinological side effects as the dosage of steroid increases with repeated administration.

Home exercise program

Both groups followed the same home-based exercise program demonstrated by a physiotherapist, including pendular movements, ROM exercises, stretching, and resistance band strengthening. Exercises were performed daily with written/visual instructions, and adherence was tracked using self-reported logs reviewed at follow-ups. We acknowledge the potential for reporting bias in self-reported exercise adherence logs. To minimize this bias, we employed concurrent verification through acknowledgement by patient bystanders or family members. Both groups were given weak analgesics, such as paracetamol for intolerable pain only, when needed.

Outcome measures

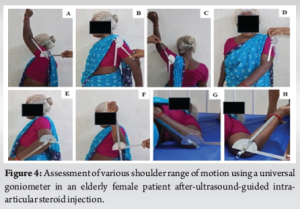

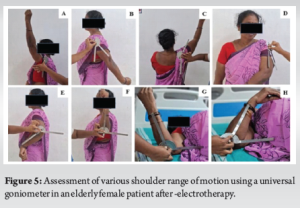

Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 1, 3, 6 months, and 1 year. The primary measure was the SPADI score (0–100), evaluating pain and disability. Secondary outcomes included ROM measurements (flexion, abduction, rotations, extension, adduction) using a goniometer, with a composite ROM score calculated for overall shoulder mobility (Figs. 4 and 5). SPADI and ROM are widely accepted and validated tools in shoulder research.

Statistical analysis

Data were verified and analyzed using Python and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Descriptive statistics, t-tests, Mann–Whitney U, and Wilcoxon tests were used as appropriate. Mixed-effects models assessed repeated measures, with subgroup analysis for diabetes. Missing data were handled using last observation carried forward and multiple imputation. Significance was set at P < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction.

Participant characteristics

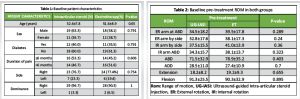

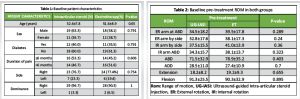

A total of 60 patients with frozen shoulder were enrolled and randomized equally into two groups: The ET group (n = 30) and the UG-IASI group (n = 30). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between the two groups, with no statistically significant differences observed in age, sex distribution, duration of symptoms, side of involvement, or presence of diabetes (all P > 0.05). The mean age was 52.6 ± 7.8 years in the IASI group and 51.6 ± 8.9 years in the ET group (P = 0.650). Both groups were predominantly right-handed and had a similar distribution of symptom laterality (Table 1). Comparison of demographic and clinical profiles between the ET and IASI groups, showing no significant differences at baseline.

ROM

Baseline pre-treatment shoulder ROM

At baseline, there were no significant differences in ROM across all shoulder movements between the two groups (P > 0.05 for all comparisons), confirming baseline comparability (Table 2).

Post-treatment shoulder ROM in both groups

Following treatment, the UG-IASI group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in most ROM measures compared to the ET group. Notably, ER at abduction improved from a median of 34.5° to 50° at 1 year in the UG-IASI group, versus 39.5° to 30° in the ET group (P = 0.002). Similar patterns were observed for internal rotation, abduction, and flexion across all follow-up points (P < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were noted between groups for adduction or extension (P > 0.05 at all-time points) (Table 3).

ROM values over time, with the IASI group showing greater early improvements in flexion, abduction, and rotations.

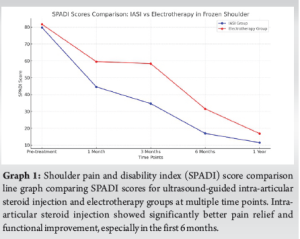

SPADI scores

Baseline SPADI scores were similar in both groups (P = 0.805). However, the UG-IASI group exhibited significantly lower SPADI scores at 1, 3, and 6 months post-intervention, indicating better pain relief and functional improvement. For instance, at 6 months, the IASI group had a mean SPADI score of 16.95 ± 15.91 compared to 31.54 ± 14.22 in the ET group (P = 0.0004). By 1 year, the difference between groups narrowed and was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.092) (Graph 1).

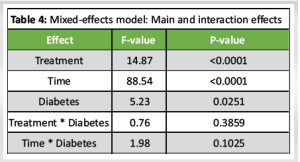

Effect of diabetes

Mixed-effects analysis showed significant effects of treatment, time, and diabetes on outcomes. Diabetes negatively impacted recovery overall (P = 0.0251), but did not alter the relative effectiveness of either treatment (P = 0.3859). Treatment, time, and diabetes showed significant main effects on outcomes, while interactions between treatment and diabetes, and time and diabetes, were not statistically significant (Table 4). Even though extensive subgroup analysis wasn’t possible due to sample size, we have considered diabetes as a key variable, which is clinically significant in frozen shoulder prognosis.

This randomized trial compared UG-IASI and ET in frozen shoulder.UG-IASI showed faster and greater improvements in pain, function, and ROM, particularly within the first 6 months. Both treatments were effective over time, but UG-IASI consistently outperformed ET in early recovery. The condition is known to follow a prolonged natural course lasting up to 2 or even 3 years in some cases, which significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and socioeconomic functioning [15,16]. Due to its chronic and often refractory nature, early and effective interventions are critical to halting disease progression and promoting recovery. Our study demonstrated that patients who received ultrasound-guided UG-IASI showed significant improvements in the SPADI scores as early as 1 month, with the most pronounced differences observed at 3 and 6 months. This is in line with previous findings by Carette et al. who found that IASI offered rapid symptomatic relief and functional gains compared to physiotherapy alone [17]. The effectiveness of corticosteroid injections in periarthritis can be attributed to their potent anti-inflammatory effects, which reduce synovial irritation and may halt the cycle of inflammation and fibrosis that underpins adhesive capsulitis pathogenesis [18,19]. Furthermore, ultrasound guidance ensures precise delivery into the glenohumeral or SASD space, thereby enhancing efficacy and reducing the risk of injection-related complications [20].

In contrast, patients managed with ET showed more gradual improvements. Although not as dramatic as UG-IASI in the early follow-up periods, improvements in pain and function were evident over time. ET, encompassing modalities, such as IFT, SWD, and therapeutic ultrasound, is aimed at modulating pain, improving circulation, and enhancing tissue extensibility. While these effects are beneficial, they tend to require repeated sessions and longer durations to produce clinically significant outcomes. The relatively slower progression of improvement in the ET group could explain the narrowing difference in SPADI scores between the two groups by the 1-year mark, where the results were no longer statistically significant [21].

ROM data further substantiated the superiority of IASI in the short to medium term. Significant gains were observed in abduction, flexion, and both internal and ER in the UG-IASI group, with improvements persisting through the 1-year follow-up. These movements are essential for performing everyday tasks, and their restriction is a hallmark of periarthritis. Interestingly, adduction and extension did not show significant intergroup differences, which may reflect the lesser functional demand or biomechanical resistance in those planes of motion. Similar patterns have been reported in other trials, where IASI led to faster restoration of overhead movements [22].

An important aspect of this study was the consideration of diabetes mellitus, a known risk factor and complicating variable in Frozen Shoulder. Our mixed-effects model revealed a significant main effect of diabetes, confirming that diabetic patients, regardless of treatment modality, experienced comparatively poorer outcomes. The study that highlighted the role of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in promoting capsular fibrosis, reduced collagen turnover, and impaired tissue elasticity [23]. However, despite the overall reduced responsiveness in diabetics, those in the IASI group still demonstrated greater functional improvement than their ET counterparts, suggesting that targeted anti-inflammatory intervention may still hold value in this subgroup. The study which similarly found that diabetic patients, though slower to recover, benefitted more from injection-based therapies than from conservative modalities alone [24].

The strengths of this study lie in its randomized design, the use of a standardized intervention protocol, long-term follow-up of 1 year, and the incorporation of both patient-reported (SPADI) and objective clinician-measured outcomes (ROM). Moreover, the use of a blinded assessor helped minimize detection bias, which is a critical component in clinical trials where blinding of treatment delivery is inherently difficult. The inclusion of a structured home exercise program across both groups added consistency in rehabilitation and reflected real-world clinical practice, where patients often receive a combination of active and passive therapy modalities. This study is not without limitations. First, the single-center design may limit the generalizability of results to broader populations, particularly those in varied healthcare systems or socioeconomic backgrounds. Second, the study did not include a true control group or sham intervention, which limits our ability to assess natural history effects. Third, although compliance with the home exercise program was monitored through patient-reported logs, more objective methods, such as wearable activity trackers, could enhance the reliability of adherence data. Finally, this study only evaluated a single steroid injection. It remains unclear whether repeat injections, or the combination of IASI followed by structured physiotherapy, might yield even greater or more durable benefits, an area worthy of future investigation.

Our findings are congruent with recent evidence advocating a multimodal approach to managing adhesive capsulitis. The studies demonstrated that combining corticosteroid injections with physiotherapy resulted in greater and faster improvements in function than either modality alone. Thus, while IASI may serve as an effective initial treatment, especially in patients needing rapid symptom control, follow-up with ET and exercise could be beneficial for maintaining long-term gains and preventing recurrence. In clinical practice, the choice of treatment should be tailored to the individual patient, considering factors, such as disease stage, comorbid conditions, pain severity, and functional limitations. Patients who require rapid symptom relief, such as manual laborers or athletes, may benefit more from IASI as a first-line intervention. On the other hand, those with contraindications to steroids or needle aversion may still achieve meaningful improvements with ET and a rigorous rehabilitation plan [25,26].

While our study had certain limitations, including its single-center design and small sample size, the use of validated outcome tools, blinded assessors, standardized treatment protocols, and clinically meaningful follow-up adds strength to the findings. The study offers practical insights into real-world treatment outcomes and provides a valuable foundation for future research in managing Frozen Shoulder.

In summary, this study provides robust evidence supporting the use of ultrasound-guided intra-articular corticosteroid injections as an effective and safe first-line intervention in patients with shoulder periarthritis. It also highlights the value of comprehensive, patient-centered rehabilitation and the importance of early intervention in altering the trajectory of this chronic, disabling condition.

In this study, UG-IASI demonstrated superior short- and mid-term outcomes compared to ET in managing frozen shoulder. UG-IASI led to more rapid improvements in pain and ROM, particularly in flexion and abduction. Although ET was beneficial, its effects were more gradual. Diabetic patients showed poorer responses across both treatments. These findings support early use of IASI within a personalized treatment strategy for optimal recovery.

Frozen shoulder is a chronic disabling condition. Ultrasound-guided intra-articular steroid injection UG-IASI offers better short- to mid-term pain relief and shoulder function than ET, enabling faster recovery & improved quality of life. A personalized approach considering patient needs and comorbidities is recommended.

References

- 1.Iordan DA, Leonard S, Matei DV, Sardaru DP, Onu I, Onu A. Understanding scapulohumeral periarthritis: A comprehensive systematic review. Life (Basel) 2025;15:186. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Zhang WB, Ma YL, Lu FL, Guo HR, Song H, Hu YM. The clinical efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma on frozen shoulder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:718. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Harna B, Gupta V, Arya S, Jeyaraman N, Rajendran RL, Jeyaraman M, et al. Current role of intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma in adhesive capsulitis of shoulder: A systematic review. Bioengineering (Basel) 2022;10:21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Tomori Y, Nanno M, Takai S. Acute calcific periarthritis of the proximal phalangeal joint on the fifth finger: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e21477. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Tang K, Sun J, Dong Y, Zheng Z, Wang R, Lin N, et al. Topical Chinese patent medicines for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Systematic review and trial sequential analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:985. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Zhu C, Huang X, Yu J, Feng Y, Zhou H. The clinical efficacy of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation technique in the treatment of scapulohumeral periarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2025;26:288. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Hernández-Secorún M, Montaña-Cortés R, Hidalgo-García C, Rodríguez-Sanz J, Corral-de-Toro J, Monti-Ballano S, et al. Effectiveness of conservative treatment according to severity and systemic disease in carpal tunnel syndrome: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:2365. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Zhang W, Luo Y, Xu J, Guo C, Shi J, Li L, et al. The possible role of electrical stimulation in osteoporosis: A narrative review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:121. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Noor MB, Rashid M, Younas U, Rathore FA. Recent advances in the management of hemiplegic shoulder pain. J Pak Med Assoc 2022;72:1882-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Çetingök H, Serçe GI. Does the application of pulse radiofrequency to the suprascapular nerve provide additional benefit in patients who have undergone glenohumeral intra-articular steroid injection and suprascapular nerve block? Agri 2022;34:272-277. https://doi.org/10.14744/agri.2022.44342. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 11.Foula AS, Sabry LS, Elmulla AF, Kamel MA, Hozien AI. Ultrasound-guided shoulder intraarticular ozone injection versus pulsed radiofrequency application for shoulder adhesive capsulitis: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Physician 2023;26:E329-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Hong T, Li G, Han Z, Wang S, Ding Y, Yao P. Comparing the safety and effectiveness of radiofrequency thermocoagulation on genicular nerve, intraarticular pulsed radiofrequency with steroid injection in the pain management of knee osteoarthritis. Pain Physician 2020;23:S295-304. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Le VT, Do PT, Nguyen VD, Nguyen Dao LT. Transforaminal pulsed radiofrequency and epidural steroid injection on chronic lumbar radiculopathy: A prospective observational study from a tertiary care hospital in Vietnam. PLoS One 2024;19:e0292042. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Chalermkitpanit P, Pannangpetch P, Kositworakitkun Y, Singhatanadgige W, Yingsakmongkol W, Pasuhirunnikorn P, et al. Ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency of cervical nerve root for cervical radicular pain: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Spine J 2023;23:651-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulder: A meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:224-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Neviaser AS, Hannafin JA. Adhesive capsulitis: A review of current treatment. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2346-56. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Carette S, Moffet H, Tardif J, Bessette L, Morin F, Frémont P, et al. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: A placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:829-38. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Cho CH, Bae KC, Kim DH. Treatment strategy for frozen shoulder. Clin Orthop Surg 2019;11:249-57. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Kim YS, Lee HJ, Bae SH, Jin H, Song HS. Outcome comparison between steroid injection and ultrasound-guided hydrodilatation in frozen shoulder: A randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020;29:715-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Shin SJ, Do NH, Lee J, Ko YW. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection in adhesive capsulitis. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1133-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Page MJ, Green S, Kramer S, Johnston RV, McBain B, Chau M, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD011275. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Sun Y, Zhang P, Liu S, Wang X, Wu Z. Intra-articular corticosteroids versus physiotherapy for the treatment of adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:519-29. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Zreik NH, Malik RA, Charalambous CP. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder and diabetes: A meta-analysis of prevalence. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2016;6:26-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Dyer BP, Burton C, Rathod-Mistry T, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Van Der Windt DA. Diabetes as a prognostic factor in frozen shoulder: A systematic review. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl 2021;3:100141. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Penning LI, De Bie RA, Walenkamp GH. The effectiveness of injections of hyaluronic acid or corticosteroid in patients with subacromial impingement: A three-arm randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:1246-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Ryans I, Montgomery A, Galway R, Kernohan WG, McKane R. A randomized controlled trial of intra-articular triamcinolone and/or physiotherapy in shoulder capsulitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:529-35. [Google Scholar | PubMed]