Diaphyseal bone tumors can mimic osteomyelitis. Carefully planned image-guided biopsies and even open biopsies with frozen section may be required to clinch the diagnosis

Dr. Mohammed Tavfiq, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Porur, Chennai - 600116, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: tavfiqmm@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor in adolescents, typically affecting the metaphyseal region of long bones. Diaphyseal osteosarcoma is rare and often mimics benign conditions such as osteomyelitis, leading to diagnostic delays.

Case Report: A 17-year-old boy presented with progressive left thigh pain and swelling for 3 months. He had a trivial injury to left thigh 7 months back while playing kabaddi. Initial radiographs, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging showed a lytic intramedullary lesion with cortical thickening, suggestive of osteomyelitis. CT-guided biopsy also revealed features consistent with chronic osteomyelitis. Later debridement with open biopsy confirmed increased reactive osteoclastic giant cells, suggestive of chronic healed osteomyelitis. Despite empirical antibiotic treatment, symptoms worsened. A second open biopsy with intraoperative frozen section (FS) revealed features of high-grade osteosarcoma. Histopathological confirmation and immunohistochemistry with SATB2 established the diagnosis. The patient was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by resection and femur reconstruction with a custom prosthesis.

Discussion: This case illustrates the diagnostic pitfalls associated with diaphyseal osteosarcoma, especially in post-traumatic settings. It has also been observed in previous research studies that early overlapping clinical and radiological features with osteomyelitis often result in misdiagnosis. Needle biopsies, while minimally invasive, may yield non-representative samples, especially in heterogeneous tumors. Open biopsy targeting the lesion’s transition zone, supported by intraoperative FS, enhances diagnostic accuracy and enables timely intervention.

Conclusion: In atypical presentations of musculoskeletal pain and swelling unresponsive to conservative treatment, malignancy should be suspected. A multidisciplinary approach, early advanced imaging, and appropriately planned biopsies are critical for accurate diagnosis and effective management of osteosarcoma.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma, osteomyelitis, computed tomography-guided biopsy, frozen section, open biopsy.

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor in the second decade of life, comprising about 20% of all primary bone malignancies with a slight male preponderance [1]. It typically affects the metaphysis of long bones, and diaphyseal osteosarcoma makes up <10% of all osteosarcoma cases [2,3].

The cause of osteosarcoma is genetic and environmental in nature. Genetic family syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, hereditary retinoblastoma, Rothmund–Thomson syndrome [4], and environmental risk factors such as radiation exposure and Paget’s disease of bone. In many circumstances, even the root of the problem may not be determined clearly. Osteosarcoma was characterized by localized pain and swelling, with pain increasing during activity. In the course of the disease, the patient has restrictions in the limb functioning, and in some cases, develops pathological fractures [5].

It is a radiologically aggressive tumor manifesting with bone destruction, periosteal reaction, and new bone formation in a benign fashion [6]. Most commonly, there is an eccentric punched-out appearance with a mixed lytic and sclerotic lesion, sunray or Codman’s triangle due to periosteal reaction. There is a common variation of the radiological features, and sometimes the manifestations may mimic osteomyelitis or benign bone lesions in the initial stage [7,8].

At the histopathological level, osteosarcoma is characterized by the existence of malignant osteoblasts that form osteoid [1]. The definitive diagnosis is made by biopsy and ancillary studies with immunohistochemical markers such as SATB2, which helps differentiate between osteosarcoma and other tumors. Current management of osteosarcoma includes neoadjuvant chemotherapy, also referred to as the methotrexate, adriamycin, cisplatin (MAP) regimen, with subsequent surgical resection. However, available improvements in care, the 5-year survival rate of osteosarcoma depends on the size of a tumor, its location, response to chemotherapy, or the presence of metastases at the time of diagnosis [9,10].

Osteosarcoma diagnosis can be difficult, and it is sometimes diagnosed when clinical symptoms are similar to other conditions, such as trauma or infection. Failure to diagnose them may result in complications and may progress, leading to a worse state. Some patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma are initially treated for osteomyelitis, as in this case, usually a delay in the administration of the proper therapy is made [11,12].

This study adds value to the comprehension of osteosarcoma due to knowledge of the diagnostic pitfalls associated with the disease in traumatized patients. This report emphasizes the necessity of initial complete clinical, radiological, and pathological assessment of such cases and to include malignancy in the differential diagnosis if the symptoms are not amenable to conservative management. The accurate diagnosis of osteosarcoma at early stages is important in boosting patient prognosis; therefore, such research studies are vital in raising awareness and the diagnostic skills involved.

A 17-year-old boy reported a history of closed injury to the left thigh while playing kabaddi 7 months back. At first, he felt only some discomfort, and he could proceed to do normal activities. Four months post-injury, there was the onset of pain in the left thigh, which was aggravated on movement and weight bearing but relieved with rest. There was no history of fever, night cries, or weight loss. The patient presented to us 6 months after the trivial injury.

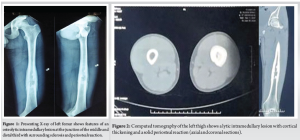

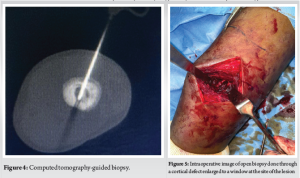

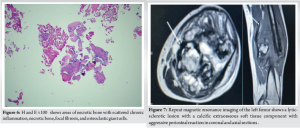

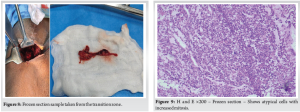

On physical examination, there was a tender, ill-defined swelling over the anterolateral aspect of the left mid-thigh. Skin over the swelling was normal. The range of motion of the left hip and knee was normal, with no distal neurovascular deficit. Initial X-ray showed features of an osteolytic intramedullary lesion at the junction of middle and distal third of left femur with surrounding sclerosis and periosteal reaction (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of left thigh showed lytic intramedullary lesion, with cortical thickening and a solid periosteal reaction, suspicious for osteomyelitis or Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Fig. 2 and 3). Based on clinical features, radiographs, and higher imaging, we had a suspicion of osteomyelitis/tumor. Since radiographs showed sclerosis and periosteal reaction, we strongly suspected Ewing’s sarcoma. Hence, CT-guided biopsy (Fig. 4) was done, which showed bone remodeling with increased osteoclastic giant cells suggestive of chronic osteomyelitis. To obtain deep cultures and since we still had a strong suspicion of malignancy, an open biopsy was planned. Open biopsy was done through a cortical defect enlarged to a window at the site of lesion (Fig. 5). However, the biopsy report showed only necrotic bone with scattered chronic inflammation, focal fibrosis, and osteoclastic giant cells suggestive of chronic osteomyelitis (Fig. 6). Culture sensitivity was done in which no organism was isolated.

Thus, the patient was treated with empirical intravenous followed by oral antibiotics. However, a couple of weeks later, he returned with an increase in the size of the swelling and severe pain. Restriction of movement in both hip and knee joints of the left limb was noted. Repeat MRI and positron emission tomography -CT was done, which showed a large lytic sclerotic lesion with calcific extraosseous soft tissue component with aggressive periosteal reaction indicative of malignancy (Fig. 7).

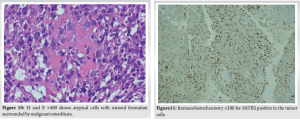

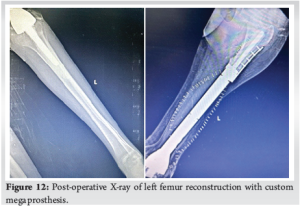

An open biopsy was again repeated along with the surgical oncology team. The tumor was exposed through the medial approach. Sample taken from the transitional zone/margin of the lesion was sent for frozen section (FS) (Fig. 8) which showed atypical cells with numerous osteoclast giant cells and chronic inflammation suggestive of high-grade sarcoma (Fig. 9). The routine histopathological examination showed atypical cells with focal area showing malignant osteoid with numerous osteoclasts such as giant cells, hemorrhage and focal necrosis (Fig. 10). Immunohistochemistry for SATB2 (Fig. 11) was strongly positive in the atypical cells with a high Ki67 proliferative index hence a diagnosis of osteosarcoma was made. The patient received five cycles of MAP chemotherapy and left femur reconstruction with custom intramedullary prosthesis with free flap coverage (Fig. 12). No adverse effects were noted during the post-operative period, but on subsequent follow-up patient developed pulmonary metastatic lesions.

The rarity of osteosarcoma and its clinical and radiological presentation overlap with benign diseases such as osteomyelitis, making diagnosing it, particularly in the diaphysis of long bones, rather difficult. Although metaphyseal osteosarcomas are more prevalent, diaphyseal osteosarcomas make up a lesser proportion and are less suspected in early assessments. This case shows how diagnostic uncertainty could cause delayed treatment.

Osteosarcoma radiologically may be confused with osteomyelitis as both exhibit large, lytic lesions with cortical thickening and periosteal reaction. Thus, the MRI features of a lytic intramedullary lesion with cortical thickening were non-specific. CT-guided biopsy was done initially in view of a strong suspicion of malignancy, which showed chronic inflammation and osteoclastic giant cells more consistent with chronic osteomyelitis rather than tumor, delaying a correct diagnosis. This stresses the well-known drawbacks of needle biopsies in identifying bone cancers, especially diaphyseal lesions. Particularly in heterogeneous tumors where necrotic and reactive regions might overshadow malignant osteoid formation, the tiny size of the biopsy needle typically leads to insufficient sampling, as demonstrated in earlier investigations. Moreover, needle biopsies are naturally limited to intralesional sampling, which complicates visualization of the vital transition zone between tumor and normal bone, where diagnostic cellular atypia is most apparent. Lacking a good picture of the lesion’s size, one runs the danger of collecting non-representative tissue, which might lead doctors to believe the diagnosis is benign. Hypertrophy and increased bone activity may be evident in early or superficial biopsies; however, without the presence of atypical cells or malignant osteoid, a diagnosis of osteosarcoma cannot be made. Hence, adequate biopsy material is essential for diagnosis and treatment. Probably a core needle biopsy at the margin of the lesion under image intensifier control would have been better than a CT-guided biopsy, where a smaller size needle is used. Advanced imaging should be done early in the process, and malignancy should be kept in mind in “trauma” cases as well.

Next, the open biopsy’s failure in this instance emphasizes sample selection in suspected cancers. This is consistent with tumor biopsy concepts, wherein precise histological evaluation depends on acquiring a sample from the transition zone where normal and malignant cells coexist. Although its efficacy depends on correct execution, open biopsy guarantees improved tissue selection by means of direct sight of the tumor.

In this situation, the surgical oncology team intervened, and an FS conducted during the open biopsy was the turning point. By showing high-grade osteosarcoma, FS analysis gave instant intraoperative data that helped with real-time surgical planning. Unlike needle biopsy, FS lets you see directly the transition zone and tumor margins, hence providing a more precise diagnosis. This not only allows quick tumor confirmation but also helps to avoid several biopsies and start early treatment.

In suspected osteosarcoma situations, the need to choose suitable biopsy methods cannot be emphasized. Research has underlined the need for tumor samples from the transition zone to seize the whole histopathological spectrum. As seen in our case, misdiagnosis might result in unsuitable treatments, including antibiotic cycles or postponement of chemotherapy start, which is vital for osteosarcoma treatment. Studies have also underlined the financial element, although needle biopsies are often seen as a cheap and less invasive choice, their lack of confirmatory power might lead to repeated surgeries, hence raising costs and postponing treatment.

Especially in diaphyseal lesions where diagnosis is more difficult, our case clearly implies that a properly planned core and not needle biopsy at the transitional zone is very important. In case of any doubt on follow-up or if the imaging does not help in defining a proper transitional zone, a planned open biopsy with FS without any hesitancy will help to clinch the diagnosis. This strategy guarantees a more representative sample, permits quick intraoperative assessment, and enables quick treatment choices, hence enhancing patient outcomes.

Al-Chalabi et al., doing a comparative analysis of proximal and distal osteosarcoma, reviewed a case of distal radius osteosarcoma that was misdiagnosed as osteomyelitis because both conditions present with symptoms such as pain and swelling and radiological findings that are similar to infection. Likewise, our patient had gradual, aching pain, as well as an intraosseous lytic lesion on imaging, suggestive of chronic osteomyelitis. Specificity of the radiological appearances like lucent lesions, cortical dysfunction, and periosteal reaction that are characteristic of osteosarcoma may resemble infectious or inflammatory processes. In conclusion, Al-Chalabi et al. stated that the presence of osteosarcoma in atypical locations significantly enhances the probability of the tumor being misdiagnosed, a notion which is well illustrated by our case [13].

Moreover, Gataa et al. emphasized the diagnostic efficacy of CT-guided core biopsy in musculoskeletal disorders. Notably, they discovered no association between the success of the biopsy and variables such as location, biopsy duration, or the number of tries. However, factors that can influence the diagnostic yield include the characteristics of the lesions, the gauge of the biopsy needle for adequate sampling, and the size of the lesion [14].

The research by Meek et al. indicates that percutaneous image-guided biopsy of bone and soft-tissue tumors is a cost-effective and precise technique for obtaining a histopathologic diagnosis; nonetheless, it requires careful consideration to mitigate possible risks. Errors in biopsy may result in misdiagnosis, postponed treatment, unnecessary invasive procedures, and significant morbidity. A comprehensive approach, with a comprehensive evaluation of clinical history and imaging, is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning [15].

Bhaker et al. underscored the significance of intraoperative pathological consultation in bone malignancies and tumor-like situations, demonstrating that the concurrent use of imprint cytology and FS yields a prompt, secure, and dependable intraoperative provisional diagnosis. Their results emphasize the need for early and precise identification of bone cancers, since some types are very aggressive and require prompt action [16].

Miwa et al. emphasized the need for histological confirmation during biopsy, indicating that while intraoperative (FS) exhibits good diagnostic accuracy, inconsistencies persist between FS, permanent section (PS), and final diagnoses in some instances. Their research indicates that surgical planning has to rely on PS diagnoses, especially for chondrogenic and osteogenic tumors, to enhance diagnostic precision and treatment results [17].

Finally, research by Mavrogenis et al. highlighted that biopsy is an essential element in the diagnostic evaluation of bone and soft-tissue cancers. The aim is to get sufficient tissue without jeopardizing local tumor spread and patient life. Their study examines conventional biopsy methods and emphasizes the rising significance of liquid biopsies as a non-invasive option for assessing tumor phenotype, progression, and medication resistance. Notwithstanding progress, obstacles such as expenses, repeatability, and isolation techniques persist. Their results emphasize that orthopedic oncologists must work in close collaboration with radiologists and pathologists to increase diagnostic precision, improve patient outcomes, and optimize health-care expenditures [18].

To sum up, various diagnostic difficulties of osteosarcoma, mainly when it resembles infection or occurs after trauma, have been described in numerous publications. In our case, as well as the reference studies, osteosarcoma should be considered if the musculoskeletal ailment does not improve with the initial treatment. Hence, a multidisciplinary approach is very essential, and correlation of clinical, radiological, and histopathological analysis and ancillary studies is very essential for diagnosis and treatment.

This case highlights diagnostic difficulties that exist between osteosarcoma and other diseases, including osteomyelitis. Misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis of osteosarcoma can contribute to either increased time to diagnosis or poorer therapy responses. As is apparent from our case and as highlighted in the literature, advanced imaging, clinical examination, a high index of suspicion, well-planned biopsy techniques, and histopathological examinations are important in diagnosis.

Diaphyseal osteosarcoma can mimic osteomyelitis, and commonly, there is confusion in diagnosis. Image-guided biopsies may occasionally fail to take representative tissue to diagnose the tumor. If there is a strong clinical suspicion of tumor, there should be no hesitancy in proceeding with an open biopsy closer to the metaphyseal region, along with an FS to “pick” up representative tumor tissue.

References

- 1.Haworth JM, Watt I, Park WM, Roylance J. Diaphyseal osteosarcoma. Br J Radiol 1981;54:932-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Savage SA, Mirabello L. Using epidemiology and genomics to understand osteosarcoma etiology. Sarcoma 2011;2011:548151. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Salom M, Chiari C, Alessandri JM, Willegger M, Windhager R, Sanpera I. Diagnosis and staging of malignant bone tumours in children: What is due and what is new? J Child Orthop 2021;15:312-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Calvert GT, Randall RL, Jones KB, Cannon-Albright L, Lessnick S, Schiffman JD. At-risk populations for osteosarcoma: The syndromes and beyond. Sarcoma 2012;2012:152382. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Bouchette P, Boktor SW. Paget bone disease. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Gaillard F, Walizai T, Knipe H. Periosteal Reaction. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org [Last accessed on 2024 Oct 22]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Subramanian S, Viswanathan VK. Lytic bone lesions. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.McDonald J, DenOtter TD. Codman triangle. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Machado I, Navarro S, Picci P, Llombart-Bosch A. The utility of SATB2 immunohistochemical expression in distinguishing between osteosarcomas and their malignant bone tumour mimickers, such as Ewing sarcomas and chondrosarcomas. Pathol Res Pract 2016;212:811-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Hanafy E, Al Jabri A, Gadelkarim G, Dasaq A, Nazim F, Al Pakrah M. Tumour histopathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in childhood solid malignancies: Is it still impressive? J Investig Med 2018;66:289-97. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Moini J, Avgeropoulos NG, Samsam M. Mesenchymal Tumours. Epidemiol Brain Spinal Tumours Elsevier eBooks. 2021 p. 243–284. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Knottenbelt DC, Kelly DF. Oral and Dental Tumours. Netherlands: Elsevier eBooks; 2011. p. 149-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Al-Chalabi MM, Jamil I, Sulaiman WA. Unusual location of bone tumour easily misdiagnosed: Distal radius osteosarcoma treated as osteomyelitis. Cureus 2021;13:e19905. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Gataa KG, Inci F, Szaro P, Geijer M. Factors affecting the success of CT-guided core biopsy of musculoskeletal lesions with a 13-G needle. Skeletal Radiol 2024;53:725-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Meek RD, Mills MK, Hanrahan CJ, Beckett BR, Leake RL, Allen H, et al. Pearls and pitfalls for soft-tissue and bone biopsies: A cross-institutional review. Radiographics 2020;40:266-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Bhaker P, Mohan H, Handa U, Kumar S. Role of intraoperative pathology consultation in skeletal tumours and tumour-like lesions. Sarcoma 2014;2014:902104. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Miwa S, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Igarashi K, Tada K, et al. Diagnostic accuracies of intraoperative frozen section and permanent section examinations for histological grades during open biopsy of bone tumours. Int J Clin Oncol 2021;26:613-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Mavrogenis AF, Altsitzioglou P, Tsukamoto S, Errani C. Biopsy techniques for musculoskeletal tumours: Basic principles and specialized techniques. Curr Oncol 2024;31:900-17. [Google Scholar | PubMed]