Lateral K-wire fixation, whether parallel or divergent, offers comparable functional and radiological outcomes to cross K-wire or three-pin techniques in type III supracondylar humerus fractures in children, with a lower risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury.

Dr. Prashant Mishra, Department of Orthopedics, Government Medical College, Seoni, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: prashantm840@gmail.com

Introduction: Supracondylar humerus fractures comprise 17% of all pediatric fractures and are second in frequency to forearm fractures. According to an epidemiological study, the incidence of fracture supracondylar humerus is 308/100000/year in the general population. It is also the most common pediatric fracture around the elbow. Fracture involving lateral condyle shows swelling, tenderness, and crepitus over lateral condyle, whereas in supracondylar fracture, tenderness and swelling involve medial supracondylar ridge and the lateral supracondylar ridge.

Objectives: (1) To assess mechanical stability and functional mobility in cross, lateral divergent, lateral parallel, and three-pin Kirschner wire fixation. (2) To assess radiological outcome in cross, lateral divergent, lateral parallel, and three-pin Kirschner wire fixation.

Materials and Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted in the hospital attached to Government Bundelkhand Medical College, Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, from July 2021 to August 2022. During this period, 60 cases of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children were treated with cross pinning and lateral pinning with Kirschner wires according to odd and even randomization.

Results: A total of 60 participants were selected with a mean age of 8.6 (±2.6) years, a minimum was 4 years, and maximum were 12 years. Thirty-nine was male and 21 was female. Out of 60 cases, 17 (28.3%) cases were operated by two cross K-wire, 18 (30%) were by two lateral k-wire divergent, 15 (25%) were by two lateral K-wire parallel, and 10 (16.7%) cases were operated by three-pin (2 lateral and 1 medial). The carrying angle of the normal elbow was 11.8 ± 1.9, 11.9 ± 2.4, 11.0 ± 1.6, 11.7 ± 1.8 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were not statistically significant.

Conclusion: In our study, two lateral divergent K-wire or two lateral parallel K-wire fixation method provided safe, better functional and radiological outcomes as well as equal mechanical stability as compared to two cross K-wire or three pinning in most of the patients.

Keywords: Supracondylar humerus fracture, type III, closed reduction, SHF, K-wire

Supracondylar humerus fractures (SHF) are the most common elbow fractures in children, particularly between the ages of 5 and 7 years, and constitute approximately 3% of all pediatric fractures [1,2]. These injuries most commonly result from a fall on an outstretched hand with the elbow in extension, leading to extension-type fractures in nearly 98% of cases, while flexion-type injuries are rare and account for only 2% [3]. Gartland classification, based on lateral elbow radiographs, is widely utilized to categorize these fractures and guide treatment [4]. Undisplaced fractures (Type I) are typically managed conservatively with posterior splinting, while displaced fractures (Types II–IV) often require closed or open reduction followed by percutaneous pinning using Kirschner wires (K-wires) to prevent complications such as malunion, cubitus varus deformity, or neurovascular injury [5,6].

Although cross-pinning with one medial and one lateral K-wire provides superior biomechanical stability, it carries a recognized risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury, particularly during medial pin insertion [7]. As a result, lateral-only K-wire fixation has gained popularity due to its safety profile, eliminating the risk of ulnar nerve injury. However, concerns have been raised about the biomechanical stability of lateral pin configurations, especially if the wires are not appropriately divergent [8,9]. While several studies have explored the outcomes of lateral pinning techniques, there remains ambiguity regarding their comparative mechanical stability and clinical outcomes in type III SHFs, particularly in Indian pediatric populations [10-12].

This study was undertaken to evaluate and compare the functional and radiological outcomes of different K-wire configurations – cross pinning versus lateral-only pinning – in the management of Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fractures in children. We specifically aimed to assess postoperative fracture stability, complication rates, and long-term functional recovery. By addressing the trade-off between biomechanical stability and neurovascular safety, this study aims to contribute region-specific data and help refine the choice of fixation method, thereby filling an existing gap in the literature concerning optimal pin configuration for displaced SHFs in children.

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Orthopedics, Government Bundelkhand Medical College and Attached Hospital, Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, for the period of 1 year from July 2021 to August 2022. During this period, 60 cases of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children were treated with cross pinning and lateral pinning with Kirschner wires according to odd and even randomization. The total study population comprised 60 children.

Sample size: For calculating sample size, we are applying the formula n = (Z2pq)/d2, where

Z = 1.96 (at 95% confidence), p = 17 (from a previous study14), q = 100-P = 83,

d (precision) = 10%

And the sample size comes out to be 54.8, adding 10% for non-response leading to 59.8 and the sample size rounded off to 60.

Inclusion criteria

- All patients aged between 4 and 14 years

- Closed Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fracture

- Duration of injury <7 days

- Normal neurological and vascular status of the affected limb

- Closed reduction wherever possible.

Exclusion criteria

- Compound fracture

- Type I and Type II

- Polytrauma patients

- More than 14 years of age

- Any pathological fractures

- Congenital deformity

- Failed closed reduction.

Ethical consideration

The protocol was presented before the Institutional ethical committee, and it was approved along with financial disclosure.

Data collection

After the patient was admitted, history of mode of injury and initial treatment was obtained from parents and children by interview method. Distal neurovascular status was thoroughly examined. Examination of the patient was done. Case sheet was prepared. The patient’s X-ray was taken in anteroposterior and lateral views. The diagnosis was established by clinical and radiological examination.

At the time of admission temporary closed reduction was done, and A/E posterior pop slab was applied in around 90° of flexion at the elbow. To lessen elbow edema, the limb was raised. All patients were taken for elective surgery as soon as possible after necessary blood, urine, and radiographic pre-operative work-up. Patients’ attenders were explained about the nature of injury and its possible complications. Patients’ attenders were also explained about the need for the surgery and the complications of surgery. Written and informed consent was obtained from the parents of the children before surgery. All patients were started on prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Intravenous cephalosporins were administered according to body weight of the children, before induction of anesthesia and continued at 12 hourly intervals post-operatively.

Surgical operation

All patients were taken up for surgery under general anesthesia. The patient was positioned supine with the ipsilateral shoulder at the edge of the table. The affected elbow, arm, and a forearm were scrubbed, painted, and drapped, leaving the elbow, lower third of arm and upper third of forearm exposed.

Longitudinal traction with the elbow in extension and supination was given. At the same time, counter traction was given by an assistant by holding the proximal portion of arm (Fig. 1).

Continuing traction and counter traction, medial or lateral displacement were corrected by valgus or varus force, respectively, at the fracture site. After that, posterior displacement and angulation were corrected by flexing the elbow and simultaneously applying posteriorly directed force from the anterior aspect of proximal fragment and anteriorly directed force from the posterior aspect of distal fragment. If an adequate reduction is obtained, the elbow should be capable of smooth and almost full flexion. Confirm the adequacy of reduction under the image intensifier in two views.

Anteroposterior view, viewing from the lateral side by externally turning the arm, and once the alignment was adequate, percutaneous K-wire fixation was used to keep the reduction in place. After experiencing failure to obtain a satisfactory reduction after two or three manipulations, we considered open reduction.

K-wire insertion: After clinical and radiological investigation, under general anesthesia, under fluoroscopy percutaneous K-wire technique was followed as soon as possible.

We used two cross K-wire, one from medial epicondyle and one from lateral condyle. After achieving satisfactory reduction through closed technique, K-wires were introduced with the help of a power drill under image intensifier control. The selection of the first pin placement was done according to initial fracture displacement. In cases of postero-medial displacement, we preferred to put medial pin first while in cases of posterolateral displacement, lateral pin was put first.

Four pinning techniques were used:

- Crossed: One medial and one lateral pin

- Divergent: Two divergent lateral pin

- Parallel: Two parallel lateral pin

- 3 pin technique: 2 lateral pin and 1 medial pin.

Medial pin entry was from tip of the medial epicondyle and lateral pin was entered at the center of the lateral condyle. Both pins were directed 40° to the humeral shaft in the saggital plane and 10° posteriorly.

K-wire placement was checked in image intensifier in anteroposterior and lateral views. K-wires were bent and kept at least 1 cm outside the skin. Sterile dressing was applied. Above-elbow posterior pop splint in 90° elbow flexion and midprone position of the forearm applied.

Post-operative management: Post-operatively, the operated limb was elevated on a drip-stand and the patient was encouraged to move fingers. At 2nd post-operative day, check dressing was done and condition of the operative wound or pin site was noted. Following dressing, check X-ray in AP and lateral views were done. Patients in whom closed reduction was done were discharged on the 3rd or 4th post-operative day, with oral antibiotics. Patients in whom open reduction was done were discharged after 5 days with oral antibiotics. These patients were reviewed on 12th post-operative day on O.P.D. basis for suture removal. K-wires were removed at 4 weeks post-operatively after X-ray confirmation of satisfactory callus formation. Pop splint was removed simultaneously, and the patient was urged to perform active elbow flexion and extension exercises as well as supination and pronation drills. Patients were advised not to lift heavy weights till 12 weeks post-operatively. Patients will be followed up at 6th week (Fig. 2).

The functional outcome and clinical results of patients were evaluated and graded using the following criteria:

- Pin tract infection

- Movements of the elbow

- Carrying angle of the elbow compared with normal elbow

- Union of the fracture

- Baumann’s angle

- Lateral rotation percentage

- Anterior humeral line (AHL).

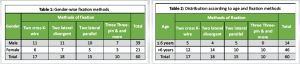

Observation and Results (Table 1)

Out of 60 cases, 17 (28.3%) cases were operated by two cross K-wire, 18 (30%) were by two lateral k-wire divergent, 15 (25%) were by two lateral K-wire parallel, and 10 (16.7%) cases were operated by three-pin (2 lateral and 1 medial) (Table 2).

A total of 60 participants were selected with a mean age of 8.6 (±2.6) years, a minimum was 4 years and maximum were 12 years. Thirty nine was male and 21 was female (Table 3).

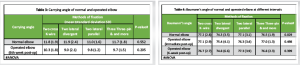

The carrying angle of the normal elbow was 11.8 ± 1.9, 11.9 ± 2.4, 11.0 ± 1.6, 11.7 ± 1.8 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were not statistically significant. The carrying angle of the operated elbow was 10.3 ± 1.8, 9.0 ± 2.1, 9.8 ± 1.2, 9.7 ± 1.5 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were not statistically significant (Table 4).

The Baumann’s angle of the normal elbow was 77.2 ± 2.8, 74.3 ± 3.5, 77.1 ± 3.1, 76.5 ± 1.9 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were statistically significant. The Baumann’s angle of the operated elbow immediately after post-operation was 77.1 ± 2.9, 75.4 ± 4.1, 76.3 ± 3.4, 77.0 ± 1.3 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were not statistically significant (Table 5).

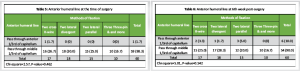

Among all the cases, at the time of surgery, except one case among the two cross K-wire group which passed through anterior 1/3rd of capitellum, rest all passed through middle 1/3rd of the capitellum (Table 6).

At the 6th week of post-surgery, the AHL passed through the anterior 1/3rd of the capitellum among a total of six cases; the rest (54) all passed through the middle 1/3rd of the capitellum. The differences in the distribution among the groups of fixations were not statistically significant (Table 7).

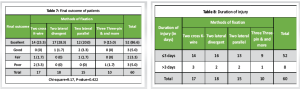

The final outcome according to Flynn’s criteria was excellent in 86.6% of cases, good in 5% of cases, fair in 3.3% of cases, and poor in 5% of cases. However, the differences in outcomes among the different groups were not statistically significant (Table 8).

Most of the cases attended hospital on or before the 3rd day of injury. 52 out of 60 patients had injury duration ≤3 days, and 8 patients had injury duration more than 3 days.

Out of 60 cases, 17 (28.3%) cases were operated by two cross K-wire, 18 (30%) were by two lateral k-wire divergent, 15 (25%) were by two lateral K-wire parallel, and 10 (16.7%) cases were operated by three-pin (2 lateral and 1 medial). Here, 39 cases were male and 21 were female patients. Historically, supracondylar humeral fractures have been more common in male child. However, Farnsworth et al. 1998 found in 391 fractures of elbow and came to the conclusion that girls experienced more fractures than boys in the age ranges of 0–1 and 6–7 [13]. A total of 60 participants were selected with a mean age of 8.6 (±2.6) years, a minimum was 4 years and maximum were 12 years. If age distribution is considered, in the 0–7-year age group, SHF is easily the most common fracture seen (28%). The mean age at which fracture supracondylar humerus occurs is 5–8 years [14]. Wilkins et al. in their study reported an incidence of 85% in patients younger than 10 years with peak age being 6–7 years and average 6.6 years. Thus, 6–7 years was the most common age group for high incidence of supracondylar fracture of humerus [15] and the mean age of occurrence of supracondylar fracture among our study participants was similar to the values found in literature. In our study, we found that most of the cases attended hospital on or before 3rd day of injury. 52 out of 60 patients had injury duration ≤3 days and 8 patients had injury duration more than 3 days. However, a study by Foead et al. [16] showed that the duration from injury to hospital admission ranged from 0.33 to 72 h with a mean of 7.23 h. Most of the patients were brought to hospital within 24 h. All the groups showed almost similar pattern of duration of injury to surgery. Sibinski et al. [17] showed no difference between patients who underwent surgery within the first 12 h and after 12 h in terms of open reduction rate, operative duration, hospital stay, and outcomes. As most of the patients came from a 100 km range from our institute, it fulfilled my inclusion criteria of duration of injury within seven 7 days. According to the results of the current study, surgical timing was found not affecting the open reduction rates. The controversy regarding the surgical parameters may be due to the varying experience level of operating room staff on orthopedics. Leet et al. [18] in their study no significant correlation between the increased time to operation and the need for open reduction. Furthermore, the length of operation, the hospital stay, or the rate of unsatisfactory results were not dependent on the delay in treatment similar results drawn in our study. Kwiatkowska et al. [19] reported that there was no clinical and radiological difference between the patients operated within the first 6 h and those operated after 12 h. Gopinathan et al. [20] in their study shortest time between injury and surgical intervention was 5 h and the longest was 136 h. Median delay from injury to surgery was 15 h. While patients with delayed presentation had somewhat greater degree of swelling around the elbow in comparison to those who presented early, there was no significant difficulty in achieving reduction and fixation. The issue of non-reducible fractures was not encountered. When the patients were compared in terms of time elapsed between injury and surgery and loss of reduction using Baumann’s angle values, no significant difference was found. In our center, patients are reaching late to the hospital they were taking approximately 3-day duration; the reason could be multiple like weakened referral system, lack of awareness, and most of peripheral roads are not connected with mainstream of city. In our study, flexion in different pinning techniques, namely two cross, two lat. divergent, two lateral parallel, and three pinning were as follows (mean ± standard deviation): 132.7 ± 2.94, 134.5 ± −5.76, 136.6 ± 6.16, and 129.8 ± 6.14. Similarly, the range of motion (ROM) in extension was 11.2 ± 7, 6 ± 6.9, 6 ± 6.32, and 7 ± 6.81. In our investigation, there were no significant differences in the ROM in flexion and extension in all the 4 groups. Although Faizan et al. [21] in their study reported that a mean loss of elbow flexion cross K-wire entry group was 8.98 ± 4.21° and in the lateral K-wire fixation group was 9.02 ± 4.12°; while mean loss of extension was 8.76 ± 4.45° and 8.96 ± 4.56° in cross K-wire entry group and lateral K-wire entry group, respectively. The difference between the two groups in terms of flexion – extension loss was not significant, which was similar to our study results. Kocher et al. [22] also found no significant differences (P > 0.05) between the lateral and medial and lateral entry pin fixation groups regarding the elbow extension, elbow flexion, which was similar to our study result [2,7]. The Baumann’s angle of the operated elbow immediately after post-operation was 77.1 ± 2.9, 75.4 ± 4.1, 76.3 ± 3.4, 77.0 ± 1.3 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were not statistically significant.

The Baumann’s angle of the operated elbow after the 6th week of post-operation was 76.7 ± 2.7, 74.8 ± 6.6, 77.3 ± 3.9, 76.8 ± 2.3 among two cross K-wire and two lateral (divergent), two lateral (parallel), three-pin K-wire groups, respectively. The differences in the angle in these groups were not statistically significant. Study done by Gopinathan et al. [13], where they compared lateral-only pin fixation in parallel and divergent configurations for Gartland Type III supracondylar humerus fractures, reported a significantly higher angle value in contrast to our study. The reported Baumann’s angle at the immediate post-operative period was 73.73 ± 4.149, at 3-week post-operative was 74.18 ± 3.573 and at 6 weeks, it was 73.64 ± 4.032 for divergent pin configuration.

Among all the cases, at the time of surgery, except one case among the two cross K-wire group which passed through anterior 1/3rd of the capitellum, rest all passed through middle 1/3rd of the capitellum. At the 6th week of post-surgery, the AHL passed through the anterior 1/3rd of the capitellum among a total of six cases; the rest (54) all passed through the middle 1/3rd of the capitellum. The differences in the distribution among the groups of fixations were not statistically significant. According to Omid et al., this line should intersect the capitellum in the middle third [23]. Similarly in our result, most of cases AHL passes through the middle third of the capitellum.

The final outcome according to Flynn’s criteria was excellent in 86.6 of cases, good in 5% of cases, fair in 3.3% of cases, and poor in 5% of cases. However, the differences in outcomes among the different groups were not statistically significant. Gopinathan et al. in their study, where they used lateral pinning for displaced supracondylar fractures in children using three Kirschner wires in parallel and divergent configuration, found that no statistically significant difference was seen in the and outcome according to Flynn’s criteria, irrespective of the wire configuration (divergent or parallel) [13].

Strengths of our study include its prospective design, uniform inclusion criteria, and standardized surgical protocols followed by all participating surgeons. The study also provides a direct comparison between four commonly used pinning techniques, including both lateral and cross configurations, contributing practical data on their comparative functional and radiological outcomes in an Indian population. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size was relatively small, particularly in the three-pin group, limiting the statistical power to detect subtle differences. The follow-up period was limited to early postoperative outcomes (6 weeks), and long-term complications such as cubitus varus deformity were not assessed. Furthermore, although all procedures were performed in a single tertiary center, variation in surgical expertise could not be fully eliminated. Finally, the study lacked blinding, which could introduce observational bias in functional outcome assessment. Future studies with larger sample sizes, longer follow-up periods, and multicentric collaboration may provide more definitive conclusions on the optimal fixation technique for pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures.

Our study concludes that it takes about 3 days, at the time of injury to the patient first reports to the hospital. Even though 3-day delay between the injury and the surgery, in all cases, we still had achieved an acceptable reduction by closed means. It did not affect the final outcome of supracondylar humerus fracture management. However, to reduce complications related to it, we still need to increase awareness among peripheral healthcare workers about early referral of these patients. The final outcome according to Flynn’s criteria was excellent in 86.6% of cases, good in 5% of cases, fair in 3.3% of cases, and poor in 5% of cases. The differences in outcomes among the different groups were not statistically significant but none of the iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury was reported in this group (lateral parallel K-wire or lateral divergent K-wire method).

Lateral-only pinning techniques, when executed with proper configuration, are a safe and effective alternative to cross pinning in pediatric type III supracondylar humerus fractures, minimizing complications without compromising stability or outcome.

References

- 1.Qiu X, Deng H, Su Q, Zeng S, Han S, Li S, et al. Epidemiology and management of 10,486 pediatric fractures in Shenzhen: Experience and lessons to be learnt. BMC Pediatr 2022;22:161. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Jones IE, Williams SM, Dow N, Goulding A. How many children remain fracture-free during growth? A longitudinal study of children and adolescents participating in the Dunedin multidisciplinary health and development study. Osteoporos Int 2002;13:990-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Brudvik C, Hove LM. Childhood fractures in Bergen, Norway: Identifying high-risk groups and activities. J Pediatr Orthop 2003;23:629-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Khosla S, Melton LJ 3rd, Dekutoski MB, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, Riggs BL. Incidence of childhood distal forearm fractures over 30 years: A population-based study. JAMA 2003;290:1479-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Kumar V, Singh A. Fracture supracondylar humerus: A review. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:RE01-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Via AG, Oliva F, Spoliti M, Maffulli N. Acute compartment syndrome. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2015;5:18-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Brubacher JW, Dodds SD. Pediatric supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008;1:190-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Vaquero-Picado A, González-Morán G, Moraleda L. Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3:526-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Dong L, Wang Y, Qi M, Wang S, Ying H, Shen Y. Auxiliary kirschner wire technique in the closed reduction of children with Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fractures. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16862. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Prashant K, Lakhotia D, Bhattacharyya TD, Mahanta AK, Ravoof A. A comparative study of two percutaneous pinning techniques (lateral vs medial-lateral) for Gartland type III pediatric supracondylar fracture of the humerus. J Orthop Traumatol 2016;17:223-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Bozinovski Z, Jakimova M, Georgieva D, Dzoleva-Tolevska R, Nanceva J. Volkmann’s contracture as a complication of supracondylar fracture of humerus in children: Case report. Sanamed 2016;11:57-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Karantana A, Handoll HH, Sabouni A. Percutaneous pinning for treating distal radial fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;2:CD006080. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Farnsworth CL, Silva PD, Mubarak SJ. Etiology of Supracondylar Humerus Fractures. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1998 Feb;18(1):38–42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Vaidya SV. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children: Epidemiology and changing trends of presentation. Int J Paediatr Orthop 2015;1:3-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Wilkins K.E. : Rockwood and green’s fractures in childrens fourth edition, Lippimcot- raven, Philadelphia : 1996. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Foead A, Penafort R, Saw A, Sengupta S. Comparison of two methods of percutaneous pin fixation in displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2004;12:76-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Sibinski M, Sharma H, Bennet GC. Early versus delayed treatment of extension type-3 supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:380-1. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Leet AI, Frisancho J, Ebramzadeh E. Delayed treatment of type 3 supracondylar humerus fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2002;22:203-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Gopinathan NR, Sajid M, Sudesh P, Behera P. Outcome analysis of lateral pinning for displaced supracondylar fractures in children using three kirschner wires in parallel and divergent configuration. Indian J Orthop 2018;52:554-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Kwiatkowska M, Dhinsa BS, Mahapatra AN. Does the surgery time affect the final outcome of type III supracondylar humeral fractures? J Clin Orthop Trauma 2018;9:S112-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Faizan M, Shaan ZH, Jilani LZ, Ahmad S, Asif N, Abbas M. Lateral versus crossed K wire fixation for displaced supracondylar fracture humerus in children: Our experience. Acta Orthop Belg 2020;86:29-35. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Kocher MS, Kasser JR, Waters PM, Bae D, Snyder BD, Hresko MT, et al. Lateral entry compared with medial and lateral entry pin fixation for completely displaced supracondylar humeral fractures in children. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg 2007;89:706-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.R. Omid et al. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children J Bone Joint Surg Am (2008) May;90(5):1121-32. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01354. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]