Calculation of Critical Shoulder Angle (CSA) helps in predicting the response to rehabilitation in patients with the Shoulder Impingement syndrome.

Dr. N C Karthik Aiyanna, Arthroscopy and Shoulder Surgery, Vale Hospital, Madurai, Ballamavatty Village and Post, Napoklu, Madikeri, Kodagu - 571214, Karnataka, India, E-mail: karthik.aiyanna@outlook.com

Introduction: A rounded shoulder with anterior tilting of the scapula is the common reason for shoulder impingement syndrome. The mainstay of treatment will be shoulder rehabilitation. While the anterior tilting of the scapula is a part of posture, the critical shoulder angle (CSA) is another anatomical factor that may influence the outcome of patients with shoulder impingement syndrome.

Aims: The study aims to identify the role of CSA defining the outcome in patients with CSA > 40° and those <40° angles undergoing the Madurai shoulder pain cure program (MSPCP), a standardized rehabilitation program.

Materials and Methods: The study was conducted as a prospective analysis with 40 participants suffering from shoulder impingement syndrome. CSA was measured on each patient, and they were divided into two groups: Group A-CSA < 40, and Group B-CSA > 40, after which they were subjected to the standardized MSPCP. The MSPCP is a rehabilitation regimen done for 3 months. This is done in phases: Phase 1 from 0 to 2 weeks, phase 2 from 2 to 6 weeks, and phase 3 from 6 to 12 weeks. The rehab regime includes scapular stabilization exercises, capsular stretching exercises, and rotator cuff isometric exercises to address pain and dysfunction associated with impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tendinitis. The participants were assessed using the Oxford Shoulder Score before the start of rehabilitation, at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months intervals, or until the symptoms were relieved. The outcomes were tabulated.

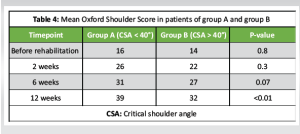

Results: Group A participants with < 40° of CSA demonstrated better functional improvements with the mean Oxford Shoulder Score of 39/48 following the MSPCP rehabilitation program compared to Group B participants with CSA more than 40° of a mean Oxford Shoulder Score of 32/48. The statistically significant difference indicates that patients with CSA < 40° had better outcomes.

Conclusion: CSA is a key factor in determining the success of conservative treatment for patients suffering from shoulder impingement syndrome. Patients with CSA < 40° showed significant improvement, and patients with CSA more than 40° showed slow improvement after rehabilitation with the MSPCP program and perhaps needed a longer time to recover.

Keywords: Shoulder impingement syndrome, scapula dyskinesia, critical shoulder angle.

The subacromial space lies between the coracoacromial arch above and the humeral head and the greater tuberosity of the humerus below. It contains the rotator cuff tendons, the long head of the biceps tendon, the shoulder joint capsule, the glenohumeral ligament, the coracohumeral ligament, and the subacromial bursa [1]. In 1972, Neer coined the term impingement syndrome and stated that impingement occurred anterolaterally at the anterior acromion and the coracoacromial ligament [2]. Subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) of the shoulder is probably the most common disorder of the shoulder and accounts for about 48% of all shoulder complaints [3].

In 1972, Dr. Charles Neer introduced the idea that rotator cuff problems were the result of contact or “impingement” of the rotator cuff tendons to the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, or the undersurface of the acromioclavicular joint. Subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) now includes a spectrum of subacromial space pathologies, which include rotator cuff tears, calcific tendinitis, biceps tendinopathy, rotator cuff tendinosis, and subacromial bursitis [4].

The etiology is multifactorial; two mechanisms, the extrinsic and intrinsic mechanisms, have been proposed to cause impingement syndrome. In the intrinsic mechanism, it is believed that internal damage to the rotator cuff tendons leads to impingement, and in the extrinsic mechanism, the impingement is believed to cause damage to the tendons [5].

The theories of extrinsic mechanism etiology tried to correlate shoulder pain to shoulder “impingement.” Hooked (type III) acromion was believed to cause “impingement” as a result of the reduced distance in the subacromial space. To date, however, it is not known whether the shape of the acromion is age-related or congenital [6].

Scapular dyskinesia is the key factor that contributes to continuing pain. A protracted and anteriorly tilted scapula and weakness of scapular muscles, particularly serratus anterior, trapezius, and levator scapulae, increases subacromial pressure and compression on the rotator cuff tendons and subacromial structures, leading to inflammation, pain, and restricted range of motion.

The critical shoulder angle (CSA) is a key anatomical parameter that has gained attention in recent years. CSA is defined as the line connecting the superior and inferior bony margins of the glenoid and a line drawn from the inferior bony margins of the glenoid to the most lateral border of the acromion [7]. Studies suggest that a CSA > 40° may predispose individuals to subacromial impingement and rotator cuff pathology. However, limited research has investigated the role of CSA in rehabilitation outcomes. We aim to analyse whether CSA influences the effectiveness of rehabilitation in managing SIS. Specifically, we hypothesize that patients with a CSA < 40° (Group A) will respond better to rehabilitation, whereas those with a CSA > 40° (Group B) will have poorer outcomes due to altered biomechanics leading to increased subacromial impingement.

How to measure (CSA)

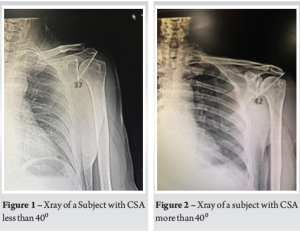

A true anteroposterior (AP) with visible joint space and only minimal overlap between the posterior and anterior rim of the glenoid is taken. A line connecting the superior and inferior bony margins of the glenoid is drawn, and another line is drawn from the inferior bony margins of the glenoid to the most lateral border of the acromion. The angle formed between these two lines is CSA.

Studies say that malrotation (internal rotation/external rotation and flexion/extension) of up to 20° hardly affects the CSA; if internal rotation and extension are beyond 20°, it increases CSA, and if external rotation and flexion are beyond 20°, it decreases CSA [7].

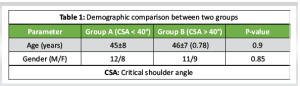

This prospective study was conducted over 12 weeks, in which 40 patients diagnosed with shoulder impingement syndrome (SIS) were considered for the study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and divided into two groups based on CSA measurements. Group A consisted of 20 patients with CSA < 40°and Group B consisted of 20 patients with CSA > 40°.

Inclusion criteria

Patients between 25 and 60 years of age presenting with complaints of shoulder pain and clinically diagnosed as SIS (positive Neer’s and Hawkins–Kennedy tests).

Exclusion criteria

- Glenohumeral osteoarthritis

- Neurological disorders affecting the shoulder

- Systemic inflammatory conditions

- History of shoulder surgery, trauma

- Rotator cuff tears (Confirmed with clinical tests).

Both groups underwent a standardized rehabilitation program focused on the following:

- Pain management: Ice therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed

- Range of motion exercises: Passive and active-assisted movements

- Postural correction: Scapular retraction and thoracic mobility exercises

- Stretching exercises: Capsular stretching exercises

- Strengthening exercises: Rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer strengthening

- Proprioceptive training: Neuromuscular control exercises for dynamic shoulder stability.

Rehabilitation (Madurai shoulder pain cure program [MSPCP]) sessions were conducted daily for 2–3 weeks, then exercises were asked to be continued at home daily for 10 weeks. The outcome of the rehabilitation program was measured using the following scores and was performed before beginning rehabilitation and during rehabilitation at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks.

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to measure the pain intensity (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain).

- The shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI) was used to assess pain and functional disability [8].

- Oxford Shoulder Score was used to assess the functional outcome [9].

Data were tabulated into Microsoft Excel and analyzed with Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences software using paired t-tests and analysis of variance to compare pre- and post-treatment values. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

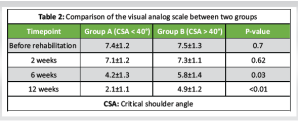

In this study, a total of 40 patients were enrolled. They were divided into two groups of 20 each based on CSA calculated using True AP view X-rays of the shoulder (Fig. 1 and 2). The age and gender difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (Table 1). The average score on the VAS before rehabilitation was 7.4 in group A and 7.5 in group B. It was statistically insignificant in the first 2 follow-ups after rehabilitation, but there was a statistically significant decrease in VAS score in group A (CSA < 40°) when compared to group B (CSA > 40°) patients at 12 weeks after rehabilitation (Table 2).

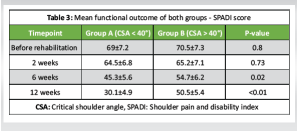

The functional outcome in both groups of patients was calculated using two scoring systems, i.e., SPADI score and the Oxford Shoulder Score. SPADI score showed no significant difference in the first 2 follow-ups after rehabilitation. There was a statistically significant decrease in SPADI score in patients with CSA < 40° when compared to CSA > 40° patients at 6 weeks after rehabilitation, and also at 12 weeks (Table 3). A similar trend was noted in the Oxford Shoulder Score which showed an insignificant difference in the first 2 follow-ups after rehabilitation. There was a statistically significant increase in the Oxford Shoulder Score in CSA < 40°when compared to CSA > 40° patients at 6 weeks after rehabilitation which improved further at 12 weeks after rehabilitation (Table 4).

In 1931, Meyer first described the extrinsic theory of rotator cuff disease, suggesting that the acromion caused mechanical attrition of the supraspinatus tendon [10]. In 1949, Armstrong stated that the mechanical conflict between the acromion and the supraspinatus tendon was the cause of so-called supraspinatus syndrome [11]. This theory was later supported and popularized by Neer, who based his conclusions on cadaveric dissection and intraoperative observation. In 1972, he introduced the term “subacromial impingement syndrome” (SIS) [12].

Moor et al. published a significant paper that introduced a radiological parameter considering both the tilt of the glenoid in the frontal plane and the acromial index. They named this parameter the CSA [7]. The CSA is defined as the angle formed by a line connecting the superior and inferior bony margins of the glenoid and a line drawn from the inferior bony margin of the glenoid to the most lateral border of the acromion. Ma et al. conducted a morphological study of the acromion and concluded that a larger CSA indicates a greater lateral extension of the acromion, which can lead to impingement syndrome [13].

Nyffeler et al. suggested that the lateral extension of the acromion alters the orientation of the deltoid fibers at their origin, thereby changing the resultant force vector of the deltoid muscle. A greater lateral extension of the acromion increases the ascending force, potentially leading to subacromial impingement and degenerative changes in the supraspinatus tendon [14].

Previous literature has shown that physical therapy is an effective conservative treatment for patients with impingement syndrome, achieving a success rate of nearly 85% within 12 weeks (with failure defined as patients opting for surgical treatment) [15,16]. Our findings also indicate that patients with impingement syndrome who underwent a focused rehabilitation program (MSPCP) experienced symptom improvement as early as 6 weeks, with many attaining complete symptom relief by 12 weeks.

Gerber et al. found that differences in CSA can lead to significant variations in joint forces. Using a simplified robotic model, they documented that a greater CSA results in increased shear forces and decreased compressive forces at the glenohumeral joint, necessitating a 35% additional force from the supraspinatus to maintain joint stability [17]. Consistent with these findings, our current study revealed that patients in Group A (CSA < 40°) showed significant improvement in Oxford Shoulder Scores compared to Group B (CSA > 40°) as early as the 6th week, with further significant improvement noted at 12 weeks post-treatment.

Patients in Group A (CSA < 40°) responded significantly better to rehabilitation, demonstrating greater pain relief, functional improvement, and increase in range of motion. On the other hand, patients in Group B (CSA > 40°) exhibited poorer outcomes, likely due to persistent subacromial impingement caused by a wider anterolateral acromial extension. These findings suggest that the CSA should be considered a predictor when designing rehabilitation programs for patients with SIS, as those with a CSA > 40° may require additional treatments or surgical interventions.

This study confirms that CSA significantly influences rehabilitation outcomes in SIS patients, with CSA < 40° being a favorable factor for recovery. Future research should explore the role of surgical interventions for patients with CSA > 40° who fail conservative management.

Shoulder impingement syndrome, one of the most common disorders affecting the shoulder joint, can be treated effectively with focused rehabilitation programs. CSA can be used to predict which patients might require adjunctive or surgical interventions and design rehabilitation programs accordingly.

References

- 1.Dhillon KS. Subacromial impingement syndrome of the shoulder: A musculoskeletal disorder or a medical myth? Malays Orthop J 2019;13:1-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Neer CS 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder. 1972. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:1399. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Van Der Windt DA, Koes BW, De Jong BA, Bouter LM. Shoulder disorders in general practice: Incidence, patient characteristics, and management. Ann Rheum Dis 1995;54:959-64. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Koester MC, George MS, Kuhn JE. Shoulder impingement syndrome. Am J Med 2005;118:452-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.McFarland EG, Maffulli N, Del Buono A, Murrell GA, Garzon-Muvdi J, Petersen SA. Impingement is not impingement: The case for calling it “rotator cuff disease”. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2013;3:196-200. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Seitz AL, McClure PW, Finucane S, Boardman ND 3rd, Michener LA. Mechanisms of rotator cuff tendinopathy: Intrinsic, extrinsic, or both? Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2011;26:1-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Moor BK, Bouaicha S, Rothenfluh DA, Sukthankar A, Gerber C. Is there an association between the individual anatomy of the scapula and the development of rotator cuff tears or osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint? : A radiological study of the critical shoulder angle. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:935-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Breckenridge JD, McAuley JH. Shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI). J Physiother 2011;57:197. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Younis F, Sultan J, Dix S, Hughes PJ. The range of the oxford shoulder score in the asymptomatic population: A marker for post-operative improvement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011;93:629-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Meyer AW. The minuter anatomy of attrition lesions. J Bone Joint Surg 1931;13:341-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Armstrong JR. Excision of the acromion in treatment of the supraspinatus syndrome; Report of 95 excisions. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1949;31B:436-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Neer CS 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983;173:70-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Ma Q, Sun C, Du R, Liu P, Wu S, Zhang W, et al. Morphological characteristics of acromion and acromioclavicular joint in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome and related recommendations: A three‐dimensional analysis based on multiplanar reconstruction of computed tomography scans. Orthop Surg 2021;13:1309-18. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:800-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: A systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009;18:138-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Ainsworth R, Lewis JS. Exercise therapy for the conservative management of full thickness tears of the rotator cuff: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:200-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Gerber C, Snedeker JG, Baumgartner D, Viehofer AF. Supraspinatus tendon load during abduction is dependent on the size of the critical shoulder angle: A biomechanical analysis. J Orthop Res 2014;32:952-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]