This case report presents a novel, joint-sparing approach to treating a rare giant cell tumor in the distal radius of a pediatric patient, emphasizing the preservation of wrist function - a critical factor often neglected in existing literature. This innovative strategy underscores the importance of early diagnosis and tailored surgical interventions, offering a significant advancement in the management of giant cell tumors in children.

Dr. Pankaj Sharma, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bathinda, Punjab, India. E-mail: dr.pankajkristwal@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a rare, locally aggressive neoplasm predominantly affecting skeletally mature individuals, with infrequent, uncommon occurrence in the pediatric population.

Case Report: This case report describes a young skeletally immature female presenting with a Campanacci grade 3 GCT of the distal radius, characterized an osteolytic lesion sparing the epiphysis. Following biopsy confirmation, the patient underwent wide local excision of the tumor with ulnar translocation, fixed using a distal radius locking plate to preserve joint integrity. Post-operative rehabilitation included physiotherapy to restore wrist mobility and grip strength.

Results: At 2 years post-surgery, the patient demonstrated no re-occurrence of tumor and satisfactory functional outcomes, including 90° dorsiflexion, 35° palmar flexion, 60° pronosupination, and 68% grip strength compared to the contralateral side.

Conclusion: This report highlights an innovative surgical approach that preserves joint functionality in pediatric GCT cases, emphasizing the importance of anatomical reconstruction and long-term functional restoration.

Keywords: Pediatric tumor, oncology, giant cell tumor, case report, literature review.

Osteoclastoma is a common, locally aggressive primary bone tumor with occasional metastatic potential. It typically involves the epiphysio-metaphyseal region of long bones and presents in the third to fourth decades with juxta-articular swelling and pain. Though primarily seen in skeletally mature individuals, rare pediatric cases are reported [1]. The Campanacci radiologic grading system classifies giant cell tumors (GCTs) based on their interaction with the bony cortex [2]. Diagnosis can be established through a percutaneous biopsy, and chest imaging is recommended to exclude the possibility of pulmonary metastasis, which occurs in approximately 1–2% of cases [2]. In clinical practice, curettage and dead space management with bone cement is appropriate for Campanacci Grade 1 and 2 lesions. Grade 3 lesions pose a technical dilemma, as it is not possible to eradicate all the tumor cells with curettage. Wide excision is usually performed for these lesions, which needs to be reconstructed [3]Vascularized fibula grafting, ulnar translocation, arthroplasty, and extra corporeal radiotherapy are all established reconstructive options [3]. Here, we describe a unique case of GCT of distal radial metaphysis in a skeletally immature female, which was managed with wide local excision of the tumor, followed by ulnar translocation fixed with a long distal radius locking plate; however, the joint was not fused. In fact, the locking plate serves to secure the transposed ulna segment to the epiphysis, preserving the integrity of the joint. Present consensus for GCT focus on preserving normal anatomical structures while ensuring complete tumor removal, minimizing recurrence, and restoring optimal function of the forearm and hand. Despite these interventions, recurrence rates remain significant, even when adjuvant therapies, such as phenol or liquid nitrogen are employed. This article describes an unusual approach to solve an unusual problem, by preserving the joint mobility, we allow the child to use it to the maximum potential.

A 12-year-old, right-hand-dominant female was brought to us by her parents with complaints of pain in the left wrist for the past 4 months, swelling since 3 months, without any history of fever, effusion, weight loss, or any similar complaints in family members. On examination, there was a swelling of (5 × 4 cm) in size, non-fluctuant, non-pulsatile, non-compressible, without any local rise of temperature. Hand function and grip strength were decreased on the left side as compared with the right side and there was no neurovascular deficit. Radiographs obtained showed a metaphyseal, osteolytic lesion with cortical breach and no periosteal reaction, which seemed to point toward an osteoclastoma of the distal radius; the epiphysis seemed to have been fortunately spared (Fig. 1 and 2). This was followed up with a biopsy, which confirmed our clinical and radiological findings. The child was diagnosed with a Campanacci Grade 3 GCT of the left distal radius and planned for wide local excision and ulnar translocation.

The patient was positioned supine after induction of general anesthesia and parts prepared and draped, and an incision was made on the dorsal aspect of the distal forearm and wrist centered over the 3rd metacarpal, the extensor retinaculum was incised, and a plane was made between the 2nd and 3rd extensor compartments. The tumor was excised along with the pseudo capsule and other unhealthy muscle, followed by extended curettage with phenol to sterilize the tumor bed. Insertion of the brachioradialis was spared. Ulnar osteotomy was planned after measuring the defect and the autograft was fixed to distal radius epiphysis with a 10 hole distal radius T plate and cortical screws followed by layered closure closely approximating the native anatomy followed by an above elbow plaster slab application kept for 2 weeks (Fig. 3), thereafter the sutures were removed and physiotherapy initiated with elbow flexion and extension, pronation and supination and grip strengthening exercises were initiated in a graded fashion.

The patient underwent regular clinical and radiographic monitoring for 1 year following the surgical intervention, with no evidence of recurrence during this period (Fig. 4 and 5). At the final follow-up appointment, the patient’s functional outcome was evaluated using the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) scoring system. This assessment tool considers both patient-specific factors, such as pain levels, functional capabilities, and emotional acceptance, as well as upper limb-specific factors, including hand positioning, lifting capacity, and manual dexterity. The child was followed up for a total period of 2 years, final dorsiflexion was 90°, palmar flexion was 35°, and pronosupination of 60° (Fig. 6). Grip strength was measured and compared with the contralateral side, measuring to be 68% of normal. At 2 years follow-up, the child scored 27 points in the MSTS score.

In adolescents, a lytic lesion of the distal radius warrants consideration of GCT, though it is rare before skeletal maturity. Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a key differential, sharing imaging features, such as fluid–fluid levels and histologic giant cells. Jain et al., noted the overlap between ABC and GCT, particularly in atypical sites [4]. Chondroblastoma, typically epiphyseal, shows chondroid matrix and immature chondroblasts, aiding distinction. Other considerations include non-ossifying fibroma, which may appear aggressive if large; telangiectatic osteosarcoma, distinguished by malignant osteoid; and brown tumors, requiring biochemical evaluation. Giant cell reparative granuloma, though rare in long bones, may mimic GCT histologically. Diagnosis requires clinical, radiological, and histological correlation. For confirmed GCT, wide excision and reconstruction are standard. Bernardes et al. reported radius allograft reconstruction with good results [5]; fibular autograft has also shown favorable outcomes [6]. GCTs of adolescents have not been well studied in the present literature. The most common location of these tumors in adolescents is around the distal femur in the epi-metaphyseal region [7-10], while other authors [9,10], describe the proximal tibia epi-metaphyseal region as the most common. GCT is described as a benign, locally aggressive tumor and carries a substantial rate of recurrence vis its counterparts in other long bones [3]. It’s periarticular nature makes it difficult to manage, while intralesional curettage and wide local excision are established management strategies, in a meta-analysis, Pazionis et al., found that 31% of patients in the intralesional group experienced a local recurrence, compared to 8% of patients in the en bloc group [11]. GCT’s of hand carry a unique feature of younger age of presentation, surpass other variants in local aggression, and often reocurr after curetting. Literature shows a higher incidence of pulmonary metastasis [12,13].

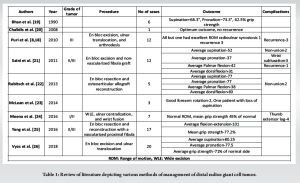

Treatment options for GCTs of the distal radius include various surgical techniques (Table 1). These techniques encompass: Extended curettage (chemical or cryoablation, use of burr), en bloc excision of the lesion followed by reconstruction using an ipsilateral proximal fibula autograft (which can be vascularized or non-vascularized) [14], tri-cortical iliac grafts, structural allografts, and distal ulnar centralization or transposition. The use of non-vascularized fibular autografts has been documented with favorable outcomes. However, complications, such as non-union (occurring in 12–38% of cases), iatrogenic fracture of graft (13–29%), and infection risks are common. Additional challenges include extended surgical times and increased comorbidities associated with the donor site.

Vascularized grafts, while beneficial, often require advanced microsurgical techniques, which can limit their application. Furthermore, allografts are typically only available in well-equipped orthopedic facilities. The preferred surgical option for Enneking Grade 3 distal radius GCT’s is wide excision followed by reconstruction of the wrist joint [15]. For this purpose, ulnar centralization or distal translocation of the ulna is described [16]. The ulnar centralization sacrifices both pronation-supination and flexion-extension at the wrist, while translocation of the distal ulna preserves pronation-supination. The ipsilateral proximal fibula (vascularized or non-vascularized), articular fibular head, osteoarticular allografts, and wrist reconstruction with endoprosthetic replacement have all been documented by authors, along with the reconstruction of the distal radius defect. These treatment options are well accepted in the adult population; GCT in the skeletally immature present’s additional layer of complexity. A Puri et al. described a case of GCT in the distal radius in a 3-year-old child, treated with resection, carpal centralization, and ulnocarpal fixation with temporary Kirschner wires [17,18]. The distal ulna in this case broadened and took on the shape of the distal radius, even contributes to the longitudinal growth of the limb. We have performed a similar procedure, resection and reconstruction with distal ulna translocation; however, we have preserved the epiphysis of the distal radius and used it to fix the ulna autograft. This allowed the child to have improved flexion-extension and pronation-supination as compared to the previous literature.

Ulnar translocation and epiphyseal fixation, sparing the wrist joint is a safe and effective choice for management of pediatric distal radius GCTs yielding good therapeutic and functional outcomes.

Giant cell tumors in the pediatric age group are rare, and under studied in the present medical literature. Ulnar translocation and fixation to the epiphysis, sparing the wrist joint is an effective method of treatment of such cases.

References

- 1. Kim WJ, Kim S, Choi DW, Lim GH, Jung ST. Characteristics of giant cell tumor of the bone in pediatric patients: Our 18-year, single-center experience. Children (Basel) 2021;8:1157-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:106-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Sullivan MH, Townsley SH, Rizzo M, Moran SL, Houdek MT. Management of giant cell tumors of the distal radius. J Orthop 2023;41:47-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Jain M, Pradhan SS, Khan S, Tripathy S, Lubaib KP, Raj KS. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the distal ulna in an elderly lady. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:79-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Bernardes M, Santos F, Frias M, Sá D, Duarte G, Lemos R. Giant cell tumor with fracture of the proximal radius – reconstructive surgery with radius allograft. J Orthop Case Rep 2020;10:32-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Ahilan S, Harshavardhan JK. Giant cell tumor of distal radius treated with wide local excision and reconstruction with ipsilateral proximal fibular autograft – a follow-up. J Orthop Case Rep 2025;15:41-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Picci P, Manfrini M, Zucchi V, Gherlinzoni F, Rock M, Bertoni F, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:486-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Puri A, Agarwal MG, Shah M, Jambhekar NA, Anchan C, Behle S. Giant cell tumor of bone in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 2007;27:635-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Kransdorf MJ, Sweet DE, Buetow PC, Giudici MA, Moser RP Jr. Giant cell tumor in skeletally immature patients. Radiology 1992;184:233-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Schütte HE, Taconis WK. Giant cell tumor in children and adolescents. Skeletal Radiol 1993;22:173-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Pazionis TJ, Alradwan H, Deheshi BM, Turcotte R, Farrokhyar F, Ghert M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of en bloc vs intralesional resection for giant cell tumor of bone of the distal radius. Open Orthop J 2013;7:103-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Cavender RK, Sale WG 3rd. Giant cell tumor of the small bones of the hands and feet: Metatarsal giant cell tumor. W V Med J 1992;88:342-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Wold LE, Swee RG. Giant cell tumor of the small bones of the hands and feet. Semin Diagn Pathol 1984;1:173-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Innocenti M, Delcroix L, Manfrini M, Ceruso M, Capanna R. Vascularized proximal fibular epiphyseal transfer for distal radial reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87 Suppl 1:237-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Murray JA, Schlafly B. Giant-cell tumors in the distal end of the radius. Treatment by resection and fibular autograft interpositional arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68:687-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Hackbarth DA Jr. Resections and reconstructions for tumors of the distal radius. Orthop Clin North Am 1991;22:49-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Puri A, Agarwal M. Treatment of giant cell tumor of bone: Current concepts. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:101-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Puri A, Gulia A, Agarwal MG, Reddy K. Ulnar translocation after excision of a campanacci grade-3 giant-cell tumour of the distal radius: An effective method of reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92:875-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Bhan S, Biyani A. Ulnar translocation after excision of giant cell tumour of distal radius. J Hand Surg Br 1990;15:496-500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Chalidis BE, Dimitriou CG. Modified ulnar translocation technique for the reconstruction of giant cell tumor of the distal radius. Orthopedics 2008;31:608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Saini R, Bali K, Bachhal V, Mootha AK, Dhillon MS, Gill SS. En bloc excision and autogenous fibular reconstruction for aggressive giant cell tumor of distal radius: A report of 12 cases and review of literature. J Orthop Surg Res 2011;6:14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Rabitsch K, Maurer-Ertl W, Pirker-Frühauf U, Lovse T, Windhager R, Leithner A. Reconstruction of the distal radius following tumour resection using an osteoarticular allograft. Sarcoma 2013;2013:318767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. McLean JM, Clayer M, Stevenson AW, Samson AJ. A modified ulnar translocation reconstruction technique for campanacci grade 3 giant cell tumors of the distal radius using a clover leaf plate. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg 2014;18:135-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Meena DK, Thalanki S, Sharma SB. Wrist fusion through centralisation of the ulna for recurrent giant cell tumour of the distal radius. Orthop Surg 2016;24:84-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Yang YF, Wang JW, Huang P, Xu ZH. Distal radius reconstruction with vascularized proximal fibular autograft after en bloc resection of recurrent giant cell tumor. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Vyas A, Patni P, Saini N, Sharma R, Arora V, Gupta SP. Retrospective analysis of giant cell tumor lower end radius treated with en bloc excision and translocation of ulna. Indian J Orthop 2018;52:10-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]