Bilateral talus fractures in children are rare and demand early diagnosis, precise imaging, and careful surgical planning to preserve vascularity and growth potential. Rehabilitation is particularly challenging due to bilateral involvement, requiring gradual weight-bearing, physiotherapy, and long-term follow-up to monitor for complications, such as avascular necrosis and joint dysfunction.

Dr. Amandeep Bainsa, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Marudhar Industrial Area, 2nd Phase, M.I.A. 1st Phase, Basni, Jodhpur - 342005, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: bains0679@gmail.com

Introduction: Pediatric talus fractures are rare and often challenging to diagnose, especially in skeletally immature patients. These injuries typically result from axial loading of the talus against the anterior tibia during dorsiflexion. Due to the unique biomechanical properties of immature bone, such fractures require significant force and are frequently associated with high-energy trauma. If missed or inadequately treated, complications, such as avascular necrosis, post-traumatic arthrosis, and delayed union may ensue.

Case Report: We present the case of a skeletally immature girl who sustained bilateral talar neck fractures (Hawkins Type 1) following a high-energy mechanism of injury. The fractures were initially overlooked during the radiological assessment. However, persistent clinical concern prompted further evaluation, including repeat imaging, which revealed the injuries. The patient was subsequently managed with surgical fixation and close follow-up.

Conclusion: This case highlights the diagnostic difficulty of pediatric talus fractures, particularly bilateral injuries, which are exceedingly rare. It underscores the importance of correlating clinical findings with imaging and maintaining a high index of suspicion in pediatric trauma cases with appropriate mechanisms of injury.

Keywords: bilateral ankle injury, bilateral foot Injury, pediatric foot injury, bilateral talus fracture, pediatric trauma

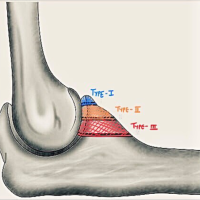

The talus develops through intramembranous (direct) ossification, initiated at specific sites characterized by cellular proliferation and vascular invasion within the mesenchymal tissue. The primary ossification center is located in the neck of the talus, and at birth, approximately 24% of the talus consists of ossified bone. During post-natal development, the talus grows predominantly in width and height rather than length. The average age of fusion of the talar ossification centers is approximately 12.9 years in males and 9.8 years in females [1]. Talar fractures were first described in 1919 by Anderson, who referred to the injury as “aviator’s astragalus,” in reference to the dorsiflexion injury mechanism observed in pilots [2]. Since then, multiple studies have examined the mechanisms, classifications, treatments, and outcomes of talar fractures, particularly in adults. In the adult population, talar fractures account for approximately 0.3% of all fractures and 3.4% of foot fractures, most commonly presenting as small chip or avulsion fractures [3]. In contrast, pediatric talar fractures are exceedingly rare, comprising only about 0.08% of all childhood fractures [4]. This rarity is primarily attributed to the increased elasticity and resistance of immature bone. Due to their infrequency, there is a limited body of literature on the treatment and long-term outcomes of talar fractures in children. Our case report, managed at a large regional trauma center, aims to address the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with these rare injuries in skeletally immature patients. While non-displaced fractures may be successfully managed with cast immobilization, displaced fractures typically require surgical intervention to minimize the risk of avascular necrosis (AVN), which is often related to vascular compromise in the talar neck [5].

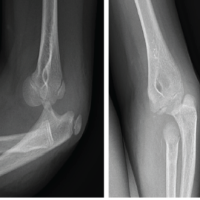

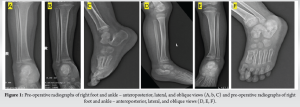

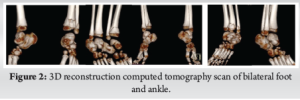

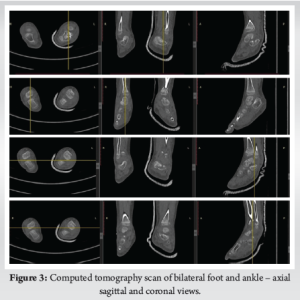

A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department of our tertiary care center with bilateral foot pain following an alleged fall from a height of approximately 30 feet. On physical examination, there was generalized swelling and tenderness over the dorsal aspect of both mid-feet, the heel of the left foot, and the forefoot on the right side. Movement of the foot and ankle was painful bilaterally, and the child was unable to bear weight, even after administration of weight-based analgesics. Further examination was limited due to reduced compliance secondary to pain and distress. Radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans were obtained (Fig. 1-3), confirming the multiple injuries. In the left foot – closed distal tibial physeal injury (Salter Harris Type 2 Injury), distal fibular physeal injury (Salter Harris Type 2), talus fracture (Hawkins Type 1) and calcaneum fracture (Schmidt and Weiner Type 5) without distal neurovascular deficit (DNVD) and in the right foot – closed fractures of the 1st and 2nd metatarsal base (Lisfranc Disruption-Hardcastle and Meyerson Type B1), base of the 3rd and 4th metatarsals; shaft of the 4th and 5th metatarsals; and talus fracture (Hawkins Type 1) without DNVD. Following initial stabilization according to advanced trauma life support protocol, bilateral below-knee slab immobilization was applied.

Initial management included immobilization with a below-knee slab and analgesia with paracetamol. Cryotherapy was administered using ice application for 10 min, 3 times daily to reduce swelling and discomfort. Following stabilization, the patient was taken to the operating theatre for definitive surgical treatment under general anesthesia. On the left side closed reduction and percutaneous fixation using K-wires was performed for the distal tibial physeal injury using two 2.0 mm K-wires. In addition, the talus was stabilized with two 2.0 mm K-wires, and the calcaneus was fixated using three 2.0 mm K-wires. A below-knee slab was applied post-operatively for immobilization. On the right side closed reduction and percutaneous fixation using K-wires was performed for the Lisfranc injury, with two 1.5 mm K-wires and conservative for right side talus fracture. A below-knee slab was applied for post-operative immobilization. (Figure 4), Post-operative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was monitored closely for signs of neurovascular compromise, infection, and appropriate healing.

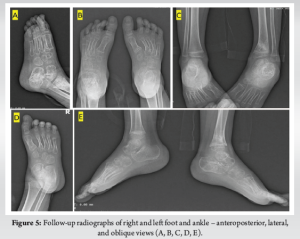

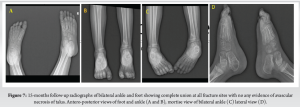

The patient was reviewed regularly in the outpatient department, with close observation of recovery progress. Kirschner wires were removed at 6 weeks post-surgery, and the below-knee immobilization was maintained for a total of 8 weeks. After slab removal, the patient began a supervised physiotherapy program focusing on ankle range of motion exercises, continued over the next 4–6 weeks. Gradual weight-bearing with the assistance of a walking frame was initiated at this stage. By the 4th post-operative month, the patient was ambulating independently without support, and radiographs confirmed satisfactory fracture union (Figure 5,6),. At the 5-month follow-up, ankle mobility had returned to near-normal levels, with both dorsiflexion and plantarflexion ranging from 0 to 15° bilaterally. Further follow-up at 15 months revealed normal range of motions at bilateral ankle (0–15° of plantar and dorsiflexion) with foot and ankle outcome score being 95% (Figure 7-9).

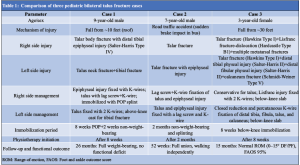

Talar fractures in the pediatric population are exceedingly rare, accounting for approximately 0.008% of all childhood fractures, in stark contrast to the 0.3% incidence reported in adults [4]. The rarity of talar fractures in children is primarily attributed to the high cartilage content and increased elasticity of the immature talus, which enables it to absorb mechanical forces more effectively without sustaining structural damage [6]. Among talar fractures, the talar neck is the most commonly involved site, followed by the body [7]. Bilateral talar fractures in children are exceptionally uncommon, with only a few isolated cases reported in the literature. Verma et al., described two pediatric cases involving bilateral talus fractures. The first case involved a physeal separation of the distal tibia and a talar body fracture with ankle subluxation on the right side, accompanied by a talar neck fracture on the left. The second case featured bilateral talar fractures with an associated epiphyseal injury of the left distal tibia [8]. The present case of a 3-year-old female with bilateral talar fractures further contributes to the limited data available on this rare injury pattern. (Table 1)

Our case report is unique due to the patient’s young age (3 years) and the complexity of injuries involving bilateral talus fractures, multiple physeal injuries, Lisfranc disruption, and a calcaneal fracture. Unlike the more localized injuries in Cases 1 and 2, this case required multi-site fixation and combined operative and conservative management. Despite the severity, the patient achieved excellent functional recovery, highlighting the potential for full rehabilitation even in extensive pediatric foot trauma. Pediatric talar fractures typically result from high-energy trauma, particularly axial loading of the dorsiflexed foot, where the talus is driven against the anterior tibial plafond [9]. These injuries are most frequently linked to falls from significant heights or motor vehicle accidents [10]. In our case, the patient sustained her injuries following a fall from approximately 30 feet, consistent with the magnitude of force required to produce bilateral talar fractures. While rare instances of talar injuries following low-energy trauma have been reported, particularly in children with ligamentous laxity or predisposing conditions, the vast majority are secondary to high-impact mechanisms [11]. The diagnosis of talar fractures in children can be clinically challenging, due to their infrequency and often subtle radiographic presentation, especially in younger children with incompletely ossified tarsal bones [12]. Non-displaced fractures may be missed on initial plain radiographs. Thus, a high index of clinical suspicion is critical in any child presenting with midfoot pain and swelling following high-energy trauma, even if initial imaging appears unremarkable. In this case, the diagnosis was confirmed only after repeat clinical assessment and advanced imaging with CT, in accordance with existing recommendations advocating for cross-sectional imaging when clinical suspicion remains high despite negative or inconclusive radiographs [13]. The management approach for pediatric talar fractures is dictated by the location and displacement of the fracture. Non-displaced fractures are generally managed conservatively with immobilization and non-weight-bearing (NWB) protocols, yielding favorable outcomes in most cases [5]. In contrast, displaced fractures, as in the present case, typically warrant surgical intervention to achieve anatomic reduction and mitigate complications, such as AVN [14]. The present literature supports the use of smooth Kirschner wires or small-diameter screws to stabilize pediatric talar fractures while preserving the integrity of open physes [15]. In this patient, bilateral closed reduction and internal fixation using K-wires was performed, aligning with established surgical practices in pediatric displaced talus fractures. The talus receives its blood supply primarily from the posterior tibial, dorsalis pedis (anterior tibial), and perforating peroneal arteries. Because its vascular architecture is largely retrograde – coursing from the neck to the body – fractures involving the talar neck or body are particularly vulnerable to AVN due to interruption of this delicate blood flow [16]. A systematic review by Waseem et al., reported an overall AVN incidence of 15.4% in pediatric talar fractures, with more severe fracture patterns correlating with higher risk [4]. Other complications include post-traumatic arthritis, delayed union, and hindfoot deformities [17]. Interestingly, some studies suggest that younger children may have a lower risk of permanent osteonecrosis following talar fractures, likely reflecting the enhanced vascular regenerative potential of the immature skeleton [18]. In the present case, no radiological or clinical signs of AVN were observed during early and later follow-up. However, long-term monitoring is essential given the potential for delayed onset of osteonecrosis and other growth-related complications. The management of pediatric talar fractures requires a tailored approach, taking into account the specific fracture configuration, the degree of displacement, and the patient’s skeletal maturity [19]. Pre-operative CT is invaluable for surgical planning, offering detailed assessment of fracture comminution, displacement, and articular surface involvement. The selection of surgical approach is typically determined by the fracture location, with anteromedial and anterolateral exposures being the most commonly employed. Tekşan and Karadeniz described the successful use of open reduction and internal fixation with cannulated screws through dual approaches in a pediatric patient with bilateral talar neck fractures [20]. In contrast, our case was managed with closed reduction and percutaneous Kirschner wire fixation, a method that minimizes soft tissue disruption and reduces the risk of physeal injury – a key consideration in skeletally immature patients. Rehabilitation in pediatric bilateral talus fractures is particularly challenging due to the need for prolonged immobilization, NWB protocols, and the psychological and physical impact of limited mobility in a growing child [21]. Unlike unilateral injuries, bilateral involvement significantly impairs a child’s ability to ambulate, participate in daily activities, and maintain independence, especially in younger patients who may lack the upper body strength to mobilize using assistive devices [22]. In the immediate post-operative phase, NWB status is typically maintained for 6–8 weeks or until radiographic signs of union are observed. During this period, it is critical to prevent disuse atrophy, joint stiffness, and deconditioning. A multidisciplinary approach involving pediatric physiotherapists is essential [8]. Passive and active range-of-motion exercises for the toes, knees, and hips should begin early to maintain joint mobility and muscle function. Once fracture healing is confirmed radiographically, gradual weight-bearing can be initiated under close supervision. Given the bilateral nature of the injury, this phase must be approached cautiously, often starting with partial weight-bearing using a walking frame or parallel bars, progressing to full weight-bearing as tolerated. Physical therapy should include proprioceptive training, balance exercises, and gait retraining to restore neuromuscular control and ensure symmetrical loading of both lower limbs. Overall, outcomes in pediatric talar fractures are favorable when anatomical alignment is restored and complications, particularly AVN, are avoided. In a long-term follow-up study, Jensen et al., reported excellent functional outcomes decades after treatment, especially in patients with minimal initial displacement [18]. Similarly, Wohler and Ellington documented full recovery without evidence of AVN or post-traumatic arthritis in a pediatric patient followed over 7 years [23]. However, because AVN and degenerative changes may develop months to years post-injury, long-term follow-up – typically over 2–3 years – is essential. Serial clinical evaluations combined with interval radiographic imaging are recommended to monitor for delayed complications. This case report is inherently limited by its single-subject design and involvement of multiple fractures of the bilateral foot and ankle. Given the extreme rarity of bilateral talus fractures in pediatric patients, the present literature remains sparse, consisting largely of individual case reports and small series. As highlighted by Vermaet al., [8] there is a pressing need for larger, multicenter studies and prospective registries to facilitate the development of evidence-based management protocols and to better define risk factors for poor outcomes in this unique patient population.

This case report underscores that pediatric bilateral talar fractures, although rare, can be effectively managed with accurate early diagnosis and appropriate surgical intervention. Early outcomes are encouraging; however, the unpredictable nature of complications, such as AVN, joint stiffness, or growth disturbances highlights the need for vigilant, long-term follow-up and monitoring.

Optimal outcomes in pediatric bilateral talus fractures rely on meticulous surgical intervention aimed at preserving vascular integrity and protecting the growth plates, followed by a structured, individualized rehabilitation program. A multidisciplinary approach is essential to reduce complications and ensure effective restoration of mobility.

References

- 1. Meier R, Krettek C, Griensven M, Chawda M, Thermann H. Fractures of the talus in the pediatric patient. Foot Ankle Surg 2005;11:5-10. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alton T, Patton DJ, Gee AO. Classifications in brief: The Hawkins classification for talus fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473(9):3046-3049. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saravi B, Lang G, Ruff R, Schmal H, Südkamp N, Ülkümen S, et al. Conservative and surgical treatment of talar fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes and complications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:8274. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Waseem S, Nayar SK, Vemulapalli K. Paediatric talus fractures: A guide to management based on a review of the literature. Injury 2022;53:1029-37. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindvall E, Haidukewych G, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr., Sanders R. Open reduction and stable fixation of isolated, displaced talar neck and body fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:2229-34. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Letts RM, Gibeault D. Fractures of the neck of the talus in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1988;8:543-5. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vallier HA, Nork SE, Barei DP, Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Talar neck fractures: Results and outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1616-24. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verma V, Batra A, Kamboj P, Bhuriya S, Singh R, Kumar S, et al. Fracture bilateral talus in children. Surg Sci 2013;4:405-9. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Byrne AM, Stephens M. Paediatric talus fracture. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012:bcr1020115028. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ibrahim I, Ye M, Smith J, Kwon JY, Miller CP. Talus fractures and concomitant injuries patterns. Foot Ankle Orthop 2019 Oct 28;4(4):2473011419S00226. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Michel-Traverso A, Ngo TH, Bruyere C, Saglini M. Talus fracture in a 4-year-old child. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr2016215063. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ribbans WJ, Natarajan R, Alavala S. Pediatric foot fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;432:107-15. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caracchini G, Pietragalla M, De Renzis A, Galluzzo M, Carbone M, Zappia M, et al. Talar fractures: Radiological and CT evaluation and classification systems. Acta Biomed 2018;89(Suppl 1):151-65. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alley MC, Vallier HA, Tornetta P 3rd, Orthopaedic Trauma Research Consortium. Identifying risk factors for osteonecrosis after talar fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2024 Jan 1;38(1):25-30 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sidhu GA, Hind J, Ashwood N, Kaur H, Lacon A. Talus fracture dislocation management with crossed kirschner wires in children. Cureus 2021;13:e13801. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwartz AM, Runge WO, Hsu AR, Bariteau JT. Fractures of the talus: Current concepts. Foot Ankle Orthop 2020;5(1):2473011419900766. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Mechelen M, Téze R, Ntoto M, O’Donnell JC, Brusseau E, Higgins J, et al. Paediatric talus fractures: A guide to management based on a review of the literature. Injury 2021;53:814-23. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jensen I, Wester JU, Rasmussen F, Lindequist S, Schantz K. Prognosis of fracture of the talus in children. 21 (7-34)-year follow-up of 14 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1994;65:398-400. [Google Scholar]

- 19. English CJ, Merriman DJ, Austin CL, Thompson SJ. Open reduction and internal fixation of a pediatric talar body fracture using a medial malleolar osteotomy – a case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:30-2. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tekşan E, Karadeniz S. Bilateral talus neck fracture in an 11-year-old patient resulting from a fall from height: A case report. J Surg Med 2022;6:72-4. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hobbs JM. Rehabilitation after fractures and dislocations of the talus and calcaneus. In: Fractures and Dislocations of the Talus and Calcaneus. Berlin: Springer; 2020. p. 311-32. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Golden-Plotnik S, Ali S, Moir M, Drendel AL, Poonai N, Van Manen M. Parental perspectives on children’s functional experiences after limb fracture: A qualitative study. Pediatr Emerg Care 2022;38:e947-52. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wohler AD, Ellington JK. Operative management of a pediatric talar body and neck fracture: A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2020;59:399-402. [Google Scholar]