Chondroblastoma is a benign epiphyseal tumor in adolescents. Early diagnosis and curettage with grafting prevent joint damage, preserve function, and reduce recurrence risk.

Dr. Mohammed Tavfiq, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: tavfiqm@gmail.com

Introduction: Chondroblastoma is a rare, benign but locally aggressive bone tumor typically affecting adolescents and young adults. It commonly arises in the epiphyseal region of long bones, particularly the distal femur. Despite its benign nature, it can cause significant joint dysfunction, pain, and disability. Early diagnosis is critical for preserving joint function and preventing recurrence.

Case Report: A 15-year-old female presented with progressive right knee pain of 6 months’ duration, worsened by weight-bearing and minimally relieved by analgesics. Clinical examination revealed tenderness and immobile swelling in the region of the medial femoral condyle. Imaging showed characteristic “chicken-wire” calcification, and computed tomography-guided biopsy confirmed chondroblastoma. The patient underwent extended curettage, iliac crest bone grafting, and the use of synthetic bone substitutes. Post-operative rehabilitation showed a good recovery in range of motion and limb function, with no recurrence at follow-up.

Conclusion: Early diagnosis and appropriate surgical management, including extended curettage and bone grafting, are essential to prevent recurrence and restore joint function in distal femur chondroblastoma. Functional outcomes are generally favorable with timely and targeted treatment.

Keywords: Chondroblastoma, distal femur, bone tumor, curettage, bone grafting, epiphyseal tumor.

Chondroblastoma is an uncommon, benign, yet locally aggressive bone tumor that originates from chondroblastic precursors in the epiphyseal regions of long bones. Accounting for fewer than 1% of all primary bone tumors, it predominantly affects adolescents and young adults, with a higher incidence in males. The most commonly involved sites include the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus, although it can occasionally occur in other epiphyseal areas. If not diagnosed and treated promptly, chondroblastoma can lead to significant morbidity, including bone destruction, joint dysfunction, and local recurrence. Patients typically present with localized pain, swelling, and restricted joint movement, often delaying diagnosis for several months. Radiologically, the lesion often appears as a well-defined lytic area with variable degrees of sclerosis and calcification, sometimes displaying the classic “chicken-wire” pattern. Although X-ray, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) help in localization and surgical planning, definitive diagnosis relies on histopathological confirmation. Histologically, chondroblastoma is characterized by sheets of round to polygonal chondroblasts with eosinophilic cytoplasm, nuclear grooves, and occasional giant cells embedded in a chondroid matrix. To reduce the chance of recurrence, the usual treatment for chondroblastoma is surgical curettage either with or without adjuvant therapy. Often used to improve local tumor control is extended curettage utilizing high-speed burrs along with adjuvant treatments such as synthetic bone replacements, bone grafting, or chemical cauterization using phenol or hydrogen peroxide. Although recurrence rates fall between 10% and 20%, appropriate surgical intervention greatly lowers the likelihood of remaining tumor development. Rarely, especially in an aggressive or recurring malignancy, more involved treatments involving en bloc resections or joint reconstruction might be required. Chondroblastoma is still a major differential diagnosis in young patients presenting with ongoing joint pain and epiphyseal lesions, given its rarity and possibility for major functional impairment. Emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and thorough treatment, advances in imaging, surgical procedures are essential for achieving favorable functional outcomes.

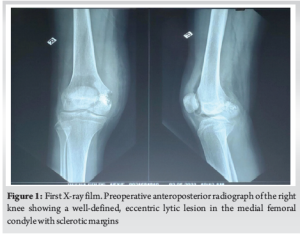

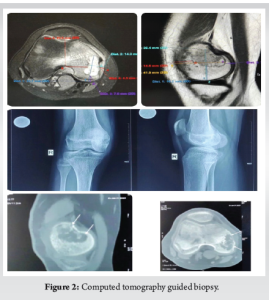

A 15-year-old girl presented with a 6-month history of right knee discomfort, which progressively worsened over time. The pain was insidious in onset and was notably aggravated by weight-bearing activities and sitting cross-legged. Although initially intermittent and relieved by analgesics, the discomfort gradually increased in intensity, interfering with her daily activities. She noticed a swelling over the medial aspect of her right knee. The swelling was progressive and unrelated to redness, warmth, or systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or appetite changes. She denied any history of trauma, previous similar complaints, or swelling in other areas. Interestingly, she reported experiencing nocturnal pain – a characteristic symptom of bone tumors – but no variation in discomfort during the day. On local examination, an irregular, poorly defined swelling was palpated 4 cm medial to the patella. The overlying skin appeared normal, with no signs of discoloration or ulceration. Further examination revealed tenderness over the medial tibial and femoral condyles. The swelling was firm, immobile, and seemed closely associated with the underlying bone. Mild suprapatellar fullness was noted. There was no joint crepitus, and the knee maintained a full range of motion from 0 to 130°. The patient’s gait was normal, and there was no limb length discrepancy. Growth plate involvement was not quantified using growth scanograms, which would be useful to monitor for potential physeal arrest or future limb length discrepancy. Radiographs showed a well-demarcated lesion in the medial femoral condyle on the anteroposterior view. MRI and CT confirmed a lesion in the medial femoral condyle. Chondroblastoma was suspected in view of the calcification of the matrix. (Fig. 1).

Performing a CT-guided biopsy of the right medial femoral condyle verified the chondroblastoma diagnosis (Fig. 2).

Histopathology showed round to polyhedral chondroblasts with eosinophilic cytoplasm, well-defined cell boundaries, and nuclei with scattered chromatin, intermingled with osteoclast-like large cells, showed. Notable was also a chondroid matrix with typical “chicken-wire” calcification, diagnostic of chondroblastoma (Fig. 3).

Under general anesthesia and tourniquet control, the medial femoral condyle was exposed by a direct medial incision and medial subvastus approach. Based on the measurements made using CT and MRI (distance of margin of lesion from the articular surface of the distal femur and anterior femur), a window was made in the medial femoral condyle and the lesion was located. Extensive curettage was performed using a burr to ensure complete removal of the tumor. The curetted tissue was sent for histopathological examination. The cavity was then thoroughly irrigated with hydrogen peroxide to eliminate residual tumor cells. Chemical adjuvants such as phenol or anhydrous alcohol were avoided due to their potential chondrotoxic effects, particularly concerning a weight-bearing epiphyseal site. Cortico-cancellous bone graft was harvested from the iliac crest. The subchondral region of the bone defect (posteriorly and distal) was layered with autograft. The residual void was filled with a mixture of autograft and 5 cc of synthetic Tricalcium phosphate bone graft substitute (Fig. 4).

Histopathological analysis of the curetted material revealed viable bone with osteoblastic rimming and nests of chondrocytes, consistent with chondroblastoma. The tumor cells were round to oval with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei exhibiting nuclear grooves, and occasional multinucleated giant cells. Although classical histological features confirmed the diagnosis, immunohistochemical markers such as S100 and DOG1 were not performed. Postoperatively, the patient was maintained on a knee brace for 4 weeks. She was mobilized without allowing weight bearing on the operated side. Gentle knee bending was started after 4 weeks. Partial weight bearing was allowed after 8 weeks (Fig. 5). Follow-up radiographs showed gradual consolidation of the bone graft and bone substitutes without any recurrence of the tumor. Radiological follow-up was performed using serial X-rays. However, MRI could have offered more detailed evaluation of graft integration, articular cartilage status, and early recurrence, particularly in an epiphyseal tumor. She was allowed full weight bearing after 4 months. Gradually, her knee movements recovered, and she had a full range of motion of the knee without any functional disability. (The rehabilitation protocol was individualized and not based on standardized guidelines). She was followed up clinically and with radiographs for 3 years (Fig. 6). Although the patient was followed for 3 years without recurrence, longer-term surveillance beyond 5 years is ideal given the potential for delayed recurrence in chondroblastoma.

Surgical treatment of chondroblastoma, especially in anatomically complex locations such as the distal femoral epiphysis, remains a significant challenge. In this case, a 15-year-old girl underwent extended curettage of the right distal femur, supplemented by synthetic bone substitutes, autologous iliac crest bone grafting, and careful post-operative management. This approach aimed to minimize recurrence, preserve joint function, and ensure an optimal functional outcome–goals that are emphasized in recent surgical literature. Achieving adequate curettage while preserving articular cartilage is crucial. effectiveness of targeted curettage combined with bone grafting to maintain both oncological safety and joint integrity. In our case, the medial subvastus approach allowed adequate visualization and access while preserving the medial collateral ligament. This technique provided good access and minimized joint morbidity.[1] In treating chondroblastoma of the distal femur, Jamshidi et al., (2024) likewise evaluated the results of intercondylar and epiphyseal techniques.[2] Their results showed better functional outcomes and reduced recurrence rates for individuals treated by the intercondylar path. Better post-operative limb function indicated by a mean Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score in their intercondylar group-29.1-than in the epiphyseal group-26.7. Furthermore, physeal injury was less prevalent in the intercondylar group and the recurrence rate was lower-6.2% versus 28.6%. In our instance, paired with bone grafting, long curettage with a burr effectively avoided recurrence and maintained joint function even though we did not use the intercondylar technique. The method of choosing should be based on the anatomical location of the tumor and emphasize obtaining total excision to minimize structural impairment. While the medial subvastus approach provided exposure in our case, comparative analysis with alternative approaches such as intercondylar or trapdoor techniques was not done in future study. Yang et al., (2024) investigated the function of anhydrous alcohol as an adjuvant treatment in chondroblastoma of the femoral head, unlike in our case, where an iliac crest bone transplant and synthetic bone replacement were employed. [3] Six pediatric patients were included in their trial, which showed good tumor control without using a procedure often linked with higher morbidity–a surgical dislocation. Their cohort’s mean MSTS score was 28, the same as in the intercondylar group of Jamshidi et al., [2] research. Although the use of anhydrous alcohol may improve local tumor management, its use in weight-bearing epiphyseal areas such as the distal femur, remains a topic of controversy owing to toxicity to surrounding cartilage. Our method avoided the likely side effects of chemical adjuvants by depending only on mechanical removal and structural repair. Patwardhan et al., (2023) [4] revealed a distinctive radiological appearance of chondroblastoma, characterized by an unusual exophytic lesion with traits beyond the anticipated epiphyseal limits. Although our example shows the more conventional results of an eccentric epiphyseal lesion with sclerotic borders and “chicken-wire” calcification, our research emphasizes the variation in radiological appearances. Typical instances could cause difficulties for diagnosis; hence, rigorous histological confirmation is necessary. Clinicians should be especially alert in differentiating chondroblastoma from other epiphyseal diseases such as osteoid osteoma, giant cell tumor, and clear cell chondrosarcoma [5-9], given the heterogeneity in presentation [9]. Direct lesion access without surgical dislocation was the creative trapdoor technique for femoral head chondroblastomas disclosed by Katagiri et al., (2022) [5]. With no local recurrence or avascular necrosis during more than 6 years of follow-up, this approach showed encouraging long-term results. Although this method was tailored to femoral head lesions, it emphasizes the changing surgical techniques meant to maintain function and guarantee sufficient tumor removal. Our case used a more conventional extended curettage technique, still the gold standard [10] for chondroblastoma of the distal femur [10-17]. These studies taken together highlight the need to choose a suitable surgical technique depending on tumor location, size, and neighboring anatomical features. Although the intercondylar method might provide better exposure for centrally positioned lesions, in our instance, the medial subvastus approach was enough to treat a medial condyle lesion while preserving joint stability. Our results coincide with the general agreement that, in treating epiphyseal chondroblastomas, extended curettage coupled with suitable structural reinforcement provides a good and long-lasting treatment. As this report describes a single case, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Larger series are required to validate these outcomes in other patients, particularly those with different tumor locations or characteristics. A long-term follow-up is still crucial to check for recurrence and evaluate functional recovery, thus guaranteeing continuous joint integrity and mobility. Psychological impacts of surgery and activity limitations were not assessed, despite their importance in adolescent recovery and quality-of-life evaluation.

Although uncommon, chondroblastoma of the distal femur presents major problems because of its epiphyseal position and propensity for recurrence. Adequate visualization of the tumor cavity, extended curettage, and proper reconstruction of the bone void “respecting” the articular cartilage, will result in good functional recovery and restoration as illustrated in this case report. Joint preservation and recurrence can be monitored only with long-term follow-up.

Chondroblastoma is a rare but aggressive epiphyseal tumor seen in adolescents. Timely diagnosis and extended curettage with bone grafting are key to preventing joint damage and preserving limb function. Early surgical intervention ensures excellent outcomes with minimal recurrence.

References

- 1. Mashhour MA, Abdel Rahman M. Lower recurrence rate in chondroblastoma using extended curettage and cryosurgery. Int Orthop. 2014 May;38(5):1019-1024. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2178-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 2. Jamshidi K, Shooroki KK, Ammar W, Mirzaei A. Does the intercondylar approach provide a better outcome for chondroblastoma of the distal femur in skeletally immature patients? Bone Joint J. 2024 Feb 1;106-B(2):195-202. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.106B2.BJJ-2023-0514.R1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 3. Yang D, Ouyang H, Zhou Z, Wang Z. Chondroblastoma of the femoral head: curettage without dislocation. BMC Surg. 2024 Nov 18;24(1):363. doi:10.1186/s12893-024-02660-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 4. Patwardhan S, Patwardhan SA. Atypical chondroblastoma of the distal femur with exophytic mass: A rare presentation and diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Orthop Surg. 2023;9(3):188-191. doi:10.18231/j.ijos.2023.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 5. Katagiri H, Takahashi M, Murata H, Wasa J, Miyagi M, Honda Y. Direct femoral head approach without surgical dislocation for femoral head chondroblastoma: a report of two cases. BMC Surg. 2022 Aug 29;22(1):327. doi:10.1186/s12893-022-01766-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 6. .Ramappa AJ, Lee FY, Tang P, Carlson JR, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Chondroblastoma of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82:1140-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Bloem JL, Mulder JD. Chondroblastoma: A clinical and radiological study of 104 cases. Skeletal Radiol 1985;14:1-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Schajowicz F, Gallardo H. Epiphysial chondroblastoma of bone. A clinico-pathological study of sixty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970;52:205-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Xu H, Nugent D, Monforte HL, Binitie OT, Ding Y, Letson GD, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone in the extremities: A multicenter retrospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:925-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Turcotte RE, Wunder JS, Isler MH, Bell RS, Schachar N, Masri BA, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone: A review of 200 cases. J Surg Oncol 1993;52:161-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Lin PP, Thenappan A, Deavers MT, Lewis VO, Yasko AW. Treatment and prognosis of chondroblastoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;438:103-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Huvos AG, Higinbotham NL, Marcove RC. Chondroblastoma: A clinicopathologic and radiologic correlation of 70 cases. Hum Pathol 1973;4:343-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L. Benign chondroblastoma of bone: A reinterpretation of the so-called calcifying or chondromatous giant cell tumor. Am J Pathol 1942;18:969-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Leithner A, Windhager R, Lang S, Haas OA, Kainberger F, Kotz R. Chondroblastoma of bone: 20 years of experience in a single institution. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1999;125:659-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Davies AM, Sundaram M, James SL. Imaging of bone tumors and tumor-like lesions. In: Techniques and Applications. Berlin: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Klein MJ, Siegal GP. Osteoblastic and chondroblastic tumors of bone. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;125:S5-18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Choudry UH, Verma S, Madewell JE, Viswanathan S, Subramanian R, Parthiban R. Surgical management and long-term outcome of chondroblastoma: Analysis of 29 cases. Indian J Orthop 2016;50:400-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]